- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Basic Industries industries

What EPR Is and Why It Matters

Ex parte re-examination (EPR) has been part of the U.S. patent system since 1981 offering a fast, relatively inexpensive way to challenge patent validity.1 EPR is often used by defendants in patent litigation to attack the patent asserted against them. However, patent owners can also use EPR to strengthen their patents more quickly than through a reissue.

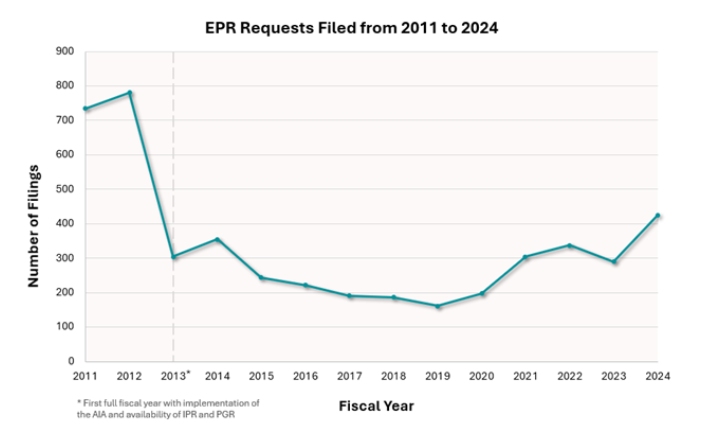

Historically, EPR filings peaked in 2012, with 780 requests submitted. After the America Invents Act (AIA) introduced inter partes review (IPR) and post-grant review (PGR), EPR filings declined sharply.2 By 2019, only 163 requests were filed in that fiscal year.3 Recently, though, EPR has been experiencing a resurgence. In 2024, filings rose to 425, and early 2025 trends suggest that filings should match or even exceed 2024 levels.4 Between Q2 and Q3 of 2025, the number of EPR requests increased from 88 to 121, likely reflecting a broader shift in practitioner strategy due to the growing difficulty in securing IPR decisions.5 If this trend continues, filings may rise even more sharply from Q3 to Q4.

Figure 1: Number of EPR requests filed annually from fiscal year 2011 through 2024. (Fig. 1 Alt. Text: Graph showing a sharp decline in EPR request filings from 780 in 2012 to 305 in 2013, with a note that 2013 was the first full fiscal year that IPR and PGR proceedings were available at the USPTO. This trend continues down to a low of 163 in 2019, but begins to rise, ending with a recent high of 425 in 2024.)

So, why the renewed interest in EPRs?

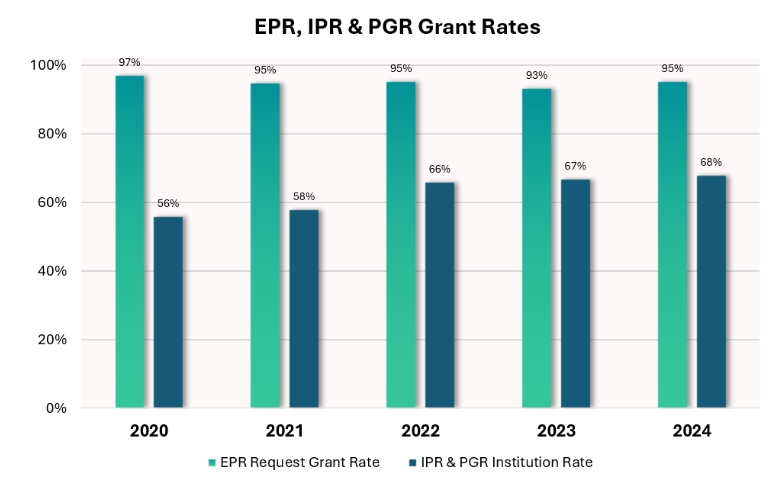

First, it is easier to obtain a notification from the USPTO that the patent will be reexamined. To initiate an EPR, a requester must show a "substantial new question of patentability" (SNQP).6 This threshold is lower than the requirements for IPR or PGR. Between 2020 and 2024, EPR requests were granted at an average rate of 95%, compared with 63% for IPR and PGR petitions.7

Figure 2: Comparison between the rate at which EPR requests are granted and IPR/PGR petitions are instituted from 2020 to 2024. (Fig. 2 Alt. Text: Graph showing the difference between the rate at which EPR requests and IPR/PGR petitions are granted. From 2020 to 2024, EPR requests were granted 97, 95, 95, 93, and 95 percent of the time, respectively. During the same period, IPR and PGR petitions resulted in institution 56, 58, 66, 67, and 68 percent of the time, respectively.)

Second, in some cases, EPR provides a chance to challenge patent validity when other post-grant proceedings fail; however, such instances can be subject to estoppel.8

Third, EPR allows for more flexible amendments, which can help patent owners strengthen their patents efficiently.9

In short, EPR is a versatile tool that merits consideration for anyone navigating patent disputes or portfolio strategy.

Statutory Framework and USPTO Procedures

The statutory basis for EPR is found in 35 U.S.C. §§ 300–307, with implementing regulations in 37 C.F.R. Part 1, Subpart D. The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) chapter 2200 provides additional guidance on the process, covering the who, what, when, and where of EPR.

Who can file an EPR?

"Any person" can file an EPR request.10 "Any person" can include: the patent owner themself, an accused infringer, a current licensee, a corporation, or even the director of the USPTO on their own initiative.11

The only exception are parties estopped under 35 U.S.C. §§ 315(e)(1) or 325(e)(1).12 These sections on estoppel prevent a petitioner, the real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner in an IPR or PGR, "of a claim in a patent under this chapter that results in a final written decision under section 318(a) . . ." from "request[ing] or maintain[ing] a proceeding before the Office with respect to that claim on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that . . . review."13

What must an EPR request contain?

An EPR request must include:

- A statement identifying each SNQ based on prior art, including patents and printed publications.14

- Identification of every claim to be re-examined.15

- A detailed explanation linking each SNQ to the claims, describing its pertinency and how the identified prior art applies.16

- Copies of:

- all prior art referenced,

- the patent in question,

- any disclaimers, certificates of correction, or prior Re-examination certificates.17

- Proof of service to the patent owner.18

- A certification that the requester is not estopped under 35 U.S.C. §§ 315(e)(1) or 325(e)(1) must also be filed.19

- Optional: proposed amendments, if filed by the patent owner.20

When can an EPR be filed?

An EPR request can be filed not only by "any person", but it can also be filed at "any time."21 This means that an EPR can be requested at any time during the patent's period of enforceability.22 That period is generally determined by adding six years to the date on which the patent expires, but it can be extended where there is pending litigation.23

Where must an EPR be filed?

A request for EPR is submitted to the USPTO, either delivered by mail, in-person, or online through Patent Center.24 Additionally, a copy of the request submitted to the USPTO must be served on the patent owner.25 If service on the patent owner is not possible, an additional copy of the EPR request should be included in the submitted request.26

Timeline of EPR

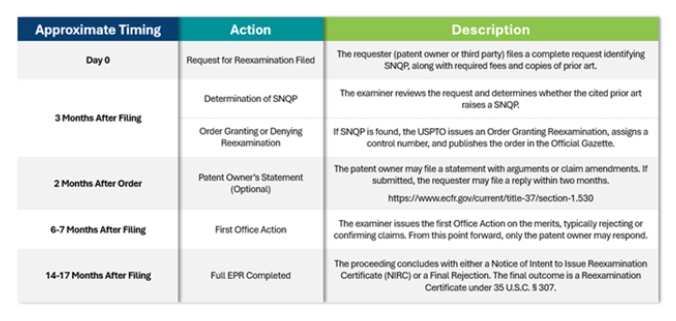

The EPR process follows a relatively predictable timeline, although specific durations can vary depending on USPTO workload and case complexity. The stages below outline the typical timing benchmarks from the initial request to final resolution.

Figure 3: Summary of the EPR timeline from filing of the EPR request to completion of EPR with issuance of a re-examination certificate. (Fig. 3 Alt. Text: Table showing the usual timeline of the EPR process, with an approximate timeline, an action, and a description column, and rows indicating a description of the actions occurring at day 0, 3 months after filing, 2 months after order, 4-6 months after filing, and 9-14 months after filing.)

Unpacking the table above, the EPR process begins when the requester files an EPR request with the USPTO.27 This request must include all the previously identified components of an EPR request.28 After the request is filed, the USPTO has three months to review and determine whether an SNQP has been raised.29 Through Q3 of 2025, though, determinations were made on average one month after filing.30 If an SNQP is raised, then an order granting re-examination is issued, along with the assignment of a control number and publishing of the order in the Official Gazette.31 If it is determined that there is not an SNQP, re-examination is refused.32

From there, if re-examination is ordered, the patent owner has two months to optionally file a statement providing arguments to consider in the re-examination process as well as proposed amendments.33 If the patent owner chooses to file a statement and is not also the requester, the requester is provided with the opportunity to file a reply within two months of service of the patent owner's statement.34 This reply ends the active participation of the requester in the EPR proceeding.35

Next, the examiner issues the first office action arising out of their re-examination.36 Most recently, first office actions have been issued around six to seven months after filing. This first office action will generally either reject or confirm the claims, and 30 days are provided for the patent owner's response.38

Finally, the proceeding nears conclusion with the issuance of either a Notice of Intent to Issue Re-examination Certificate or a Final Rejection.39 The final step is issuance and publication of a Re-examination Certificate, which cancels claims determined to be unpatentable, confirms claims determined to be patentable, and incorporates any proposed amended or new claims determined to be patentable.40 This conclusion has been reached recently within fourteen to seventeen months from filing.41

Conclusion

It's clear that EPR is experiencing a resurgence in today's patent landscape. With its low threshold for initiation, broad eligibility for requesters, and streamlined process, EPR has reemerged as a practical and cost-effective mechanism for both patent owners and challengers alike.

Because an EPR request may be filed at any time during a patent's enforceability period, it remains one of the most flexible tools in the USPTO's post-grant arsenal. As patent strategies continue to evolve, EPR is proving to be far more than a legacy mechanism—it is a strategic, adaptable pathway that compliments modern patent portfolio management.

This article is the first part of Finnegan's five-part EPR Academy series, which sets out to explore the renewed role of EPR in the current patent environment. The next edition will provide a step-by-step guide through the EPR process, from filing to final certificate, with future editions diving into best strategies in utilizing EPR, as both patentee and patent challenger.

Footnotes

1 MPEP § 2209 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

2 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Ex Parte Re-examination Filing Data – September 30, 2024 (2024).

3 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Ex Parte Re-examination Filing Data – September 30, 2024 (2024).

4 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Re-examinations – FY 2025 (2025).

5 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Re-examinations – FY 2025 (2025).

6 35 U.S.C. § 304.

7 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Workload Tables (2024); U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, PTAB Trial Statistics FY24 End of Year Outcome Roundup IPR, PGR (2024).

8 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(6).

9 MPEP § 2221 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

10 35 U.S.C. § 302.

11 MPEP 2212 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

12 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(a).

13 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(6); 35 U.S.C. §§ 315(e)(1), 325(e)(1).

14 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(1).

15 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(2).

16 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(2).

17 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(4).

18 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(5).

19 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(6).

20 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(e).

21 35 U.S.C. § 302.

22 MPEP § 2211 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

23 MPEP § 2211 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

24 MPEP § 2210 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

25 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(5).

26 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(b)(5).

27 37 C.F.R. § 1.510(a).

28 Supra notes 15–20.

29 37 C.F.R. § 1.515(a).

30 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Re-examinations – FY 2025 (2025).

31 37 C.F.R. § 1.525.

32 37 C.F.R. § 1.515(c).

33 37 C.F.R. § 1.530(b).

34 37 C.F.R. § 1.535.

35 37 C.F.R. § 1.550(f).

36 37 C.F.R. § 1.550(b).

37 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Re-examinations – FY 2025 (2025).

38 37 C.F.R. § 1.550(b).

39 MPEP § 2287 (9th ed. Rev., Jan. 2024).

40 37 C.F.R. § 1.570; 35 U.S.C. § 307.

41 U.S. Pat. & Trademark Office, Re-examinations – FY 2025 (2025).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.