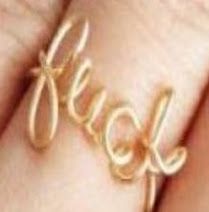

Erik Brunetti, famous in the trademark world for knocking the scandalous and immoral provision of Section 2(a) out of the Lanham Act [TTABlogged here], returned to the TTAB in this battle over the proposed mark FUCK for phone cases, jewelry, bags, and retail store services, in four separate applications. The Board affirmed each of the refusals to register on the ground that FUCK fails to function as a trademark, concluding that the "fuck" is in such widespread use that it does not create the commercial impression of a source indicator, but rather expresses well-recognized, familiar sentiments. The Board rejected Brunetti's argument that the Supreme Court decision in the FUCT case requires reversal here, and it also rejected his claim of biased treatment by the Board. In re Erik Brunetti, 2022 USPQ2d 764 (TTAB 2022) [precedential] (Opinion by Judge Mark Lebow).

The failure-to-function refusal was rather straightforward. The Board pointed out that Sections 1, 2, 3, and 45 of the Trademark Act serve as the statutory basis for the refusal. Sections 1 and 2 provide for registration of "trademark[s] by which goods of the applicant may be distinguished from the goods of others." Section 3 states that service marks are registrable "in the same manner and with the same effect as trademarks." Section 45 defines a "trademark" and a "service mark" as something that identifies and distinguishes goods and services from those of others.

If the evidence shows that consumers would not perceive the proposed mark as performing the Congressionally-defined functions of a trademark under Section 45, then, under Sections 1 and 2 – which all require 'trademarks' – such proposed marks may not be registered.

The Board and its reviewing courts have for decades held that "[s]logans and other terms that are considered to be merely informational in nature . . . are not registrable." Merely informational matter includes common terms that consumers are "accustomed to seeing used by various sources to convey ordinary, familiar, or generally understood concepts or sentiments."

Examining Attorney Curtis W. French submitted evidence in two categories: evidence showing the ubiquity of the word FUCK in general, and evidence showing widespread use of the word FUCK for various consumer goods.

Applicant suggests that he intends to use FUCK . . . to critique capitalism, government, religion and pop culture. Applicant thus concedes that he intends to use FUCK as the word is commonly understood, to convey the sentiment he hopes prospective consumers of his goods and services will take away from its display.

Applicant Brunetti offered several feeble and unsuccessful arguments seeking to undermine the evidence, and he also erroneously claimed that the Office found only that the word FUCK was "widely-used," but not that it failed to function as a trademark. He provided no evidence that rebutted the Examining Attorneys' showing regarding consumer perception of the word FUCK.

The record before us establishes that the word FUCK expresses well-recognized familiar sentiments and the relevant consumers are accustomed to seeing it in widespread use, by many different sources, on the kind of goods identified in the FUCK Applications. Consequently, we find that it does not create the commercial impression of a source indicator, and does not function as a trademark to distinguish Applicant's goods and services in commerce and indicate their source. Team Jesus, 2020 USPQ2d 11489, at *18-19. Consequently, Applicant cannot appropriate the term exclusively to itself, denying others the ability to use it freely. "'[I]t is the type of expression that should remain free for all to use.'" Univ. of Kentucky v. 40-0, LLC, 2021 USPQ2d 253, at *36 (quoting Eagle Crest, 96 USPQ2d at 1230).

The Board rejected Brunetti's contention that the Supreme Court's decision in Iancu v. Brunetti controls here. That case concerned only Section 2(a)'s prohibition of registration of marks containing scandalous matter.

Nothing in Iancu v. Brunetti requires the USPTO to register a term that would have been refused under Section 2(a) if it is otherwise unregistrable under other provisions of the statute. The First Amendment does not require the USPTO, through federal registration, to confer on any applicant the exclusive right to use an expressive term that fails to function as a mark and thereby deny others the ability to use it freely.

Brunetti claimed that the USPTO is biased against him: "[T]he PTO has granted dozens of registrations for FUCK. It just refuses to approve [Applicant's] application because he is [Applicant]." The Board was unmoved. All of the registered marks include other wording in addition to FUCK. In any event, the Office makes registrability determinations based on the particular mark, goods, and services in each case. Furthermore, the refusal at hand was issued not because Brunetti's uses the word FUCK, but on the word's failure to function as a trademark.

Applicant has not provided any evidence that plausibly suggests the USPTO maintains any bias against him for prevailing in his appeal of the Office's refusal to register a different word (FUCT) based on a different statutory basis (Section 2(a)'s now invalidated scandalous and immoral provision), or is motivated by his exercise of his first amendment rights.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.