- within Tax topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy and Securities & Investment industries

Key Takeaways:

- High-net-worth individuals often have multiple income streams and need to coordinate tax strategies across entity types and asset classes.

- The proper structuring of investments can often have a significant positive impact on the economic gain realized.

- Start to plan at least 18 to 24 months before the sale of a closely held business to ensure proper structure, boost business valuation, and improve after-tax outcomes.

You've built significant wealth. As a result, taxes have become more than just a line item in your budget — they're a force that can quietly erode your returns, complicate your business exit, and reshape your legacy.

Fortunately, you have a window of opportunity to take control. Proactive tax planning can help you align today's strategies with tomorrow's vision — whether you're juggling multiple businesses, eyeing a potential sale of an investment, or preparing to transition out of your company.

This article examines how to approach tax planning to maximize your earnings and stay ahead as tax laws shift.

Understanding the Tax Implications of Different Income Streams

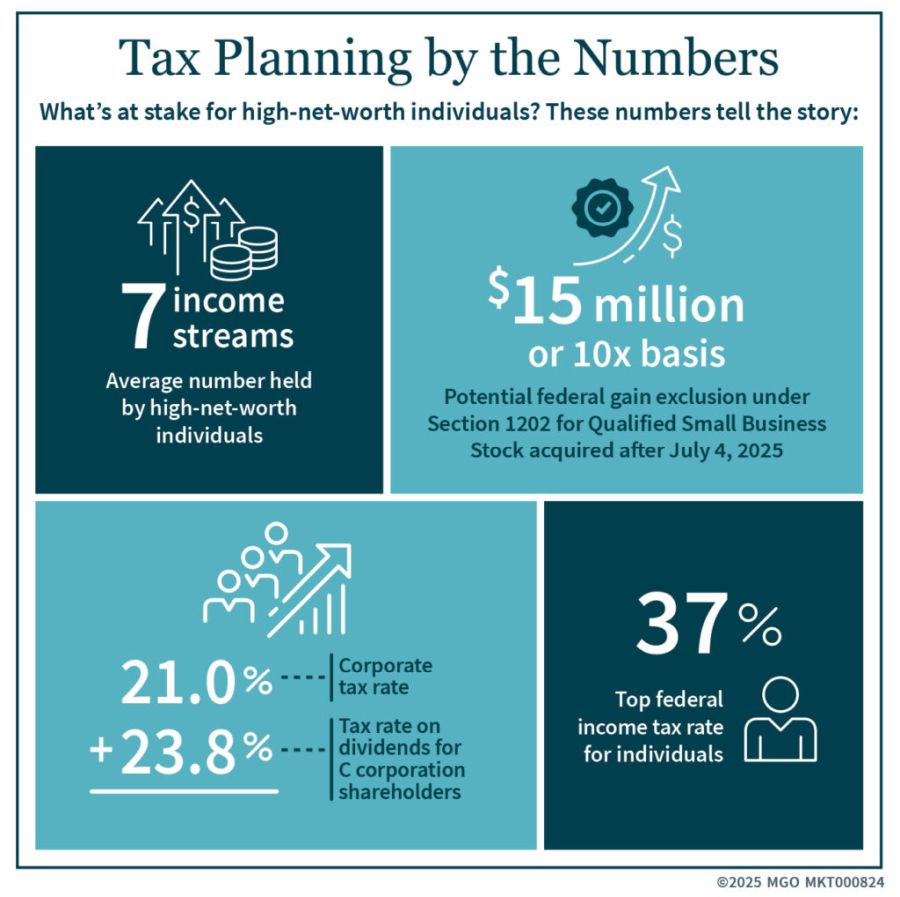

The average high-net-worth individual typically has around seven income streams. These can include salaries and wages, pensions and annuities, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental and royalties, business profits, and more.

Each type of income can face different tax rules and rates — which makes planning across all sources critical.

For example, you might defer income into years where your marginal rate is lower (such as in retirement or during a gap year after a business sale), accelerate deductions in high-income years to offset earnings, or swap investment property using a 1031 like-kind exchange to defer recognition of capital gains.

Strategically harvesting investment losses can also help manage bracket thresholds and your exposure to the net investment income tax (NIIT).

Also, consider how you generate income through various entities. Sometimes, an investment's structure can have a greater impact on tax outcomes than the investment itself.

For example, at the federal level, income from a C corporation is taxed at both the corporate (21%) and shareholder levels (up to 23.8% on dividends), resulting in effective tax rates that leave less than half of earnings in your control once you layer in state taxes. In contrast, S corporations and other passthrough structures may offer favorable pass-through treatment and qualify for a QBI deduction (20% of the business income).

Planning for Business Exits with Taxes in Mind

Selling a closely held business may be a once-in-a-lifetime event. The company may make up a large portion of your net worth and, with so much at stake, the tax treatment of the sale can dramatically alter the outcome.

We recommend that business owners start preparing for a sale at least 18 to 24 months in advance. But even if a sale isn't on the immediate horizon, business owners should operate as though the company is always "for sale". Opportunities often arise unexpectedly and financials that aren't sale-ready can delay or derail a deal. Minimize all working capital kept in the business for at least the year preceding a sale. You will not be paid any more money for a business with a ton of working capital versus the minimum.

A knowledgeable CPA can help you identify red flags, clean up reporting, and implement strategies that improve the business's financial profile so you're prepared to act when the timing is right.

A longer timeline gives you runway to halt unnecessary reinvestment and boost earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) — directly affecting the sale price and reducing excess working capital.

Structuring the Deal

The structure of a sale plays a crucial part in the tax treatment of potential gains. Many sales of closely held businesses take the form of asset sales rather than stock sales, mainly because asset purchases offer more favorable terms to the buyer. When a buyer purchases the company's assets, they avoid inheriting legacy liabilities and can allocate the purchase price among depreciable assets for future tax benefits.

However, even for transactions legally structured as a stock sale, buyers may use a Section 338(h)(10) election to treat the deal as an asset sale for tax purposes. This hybrid structure provides the buyer with the benefits of an asset acquisition while technically acquiring the stock.

From the seller's perspective, both methods can yield similar tax outcomes. The gain from the sale typically flows through to the owner as a capital gain. If any portion of the purchase price is allocated to depreciated fixed assets, there may be a small amount of ordinary income due to depreciation recapture. As long as the owner is actively involved in the business at the time of sale, it's generally exempt from the 3.8% NIIT.

In some cases, especially in deals involving private equity, buyers want to retain the existing owner's involvement, so the buyer may acquire a majority interest and require the seller to continue managing the business. This is often structured through an F-reorganization, which allows for tax deferral on the portion of the business not immediately sold.

Another common feature of modern deals is the earnout: a portion of the sale price that's paid over time based on the company's future performance — usually tied to EBITDA targets. Earnouts can create significant tax planning opportunities and risks when they extend over several years.

Finally, for owners concerned about a large tax hit, investing the gain into Qualified Opportunity Zone (QOZ) funds can provide a way to defer capital gains and potentially reduce future taxes. This benefit was made permanent by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

Working closely with a CPA who understands these nuances allows you to align the terms of the sale with your broader financial goals.

Potential Section 1202 Tax Saving Strategies

Selling qualified small business stock (QSBS) may qualify for Section 1202 treatment. This tax provision allows individuals to avoid paying taxes on up to 100% of the taxable gain recognized on the sale of QSBS. The gain exclusion is worth $10 million or 10 times investment basis and applies to C Corporation stock issued after August 10, 1993, and before July 4, 2025, held for at least five years.

The recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act increases the Section 1202 exclusion for gain to $15 million or 10 times basis for QSBS acquired after July 4, 2025, and held for at least five years. There is a reduced gain excluded if the stock issued after July 4, 2025, is only held for three years (50% exclusion) or four years (75% exclusion).

Section 1202 creates an effective tax rate savings of up to 23.8% for federal income tax, and many states follow the federal treatment — resulting in even more substantial savings.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.