- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

On June 14, 2023, the Internal Revenue Service and the Treasury Department issued (among other guidance) an expansive set of proposed regulations explaining how taxpayers can monetize 11 green energy tax credits through transferability (the ability to transfer or sell the credit to an unrelated taxpayer). The transferability feature for various green energy tax credits included in the Inflation Reduction Act makes it possible for a larger universe of taxpayers to take advantage of the credits, since they will not be reliant on entering into complicated tax equity structures to see a benefit.

Prior to the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) (P.L. 117-169), it was illegal to buy and sell the federal tax credits generated by renewable energy projects and most other assets. Instead, developers of these projects were able to enter into joint-ventures and leasing arrangements with other private companies that had a sufficient tax liability. These arrangements are known as "tax equity" and are relatively complex financing structures. This has created a bottleneck on the deployment of renewable energy over the last several decades. Generally, only large financial institutions with project finance underwriting capabilities and a small cohort of non-financial companies have been repeat "tax equity" investors.

The transferability feature for various green energy tax credits included in the IRA makes it possible for a larger universe of taxpayers to take advantage of the credits since they will not be reliant on entering into complicated tax equity structures to see a benefit. While the tax equity market was some $20 billion to $30 billion per year before this feature and a companion "direct pay" feature were enacted in the IRA, it is expected that the market for tax credits will double or triple because of these new provisions. The complexity, unfavorable generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) accounting treatment and various risks that the IRS requires be borne by tax equity investors has kept many would-be investors on the sidelines. The simplicity of tax credit transferability should bring these investors off the sidelines.

Transferability is effected by an election under new Tax Code Section 6418 and is only available for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2022. This election is generally available to entities other than a very limited subset of entities that are eligible for "direct pay" in which the tax credit becomes refundable from the IRS.

Also on June 14, 2023, the IRS and the Treasury issued temporary regulations (TD 9975) containing rules that require taxpayers seeking to make the Section 6418 transferability election to register with the IRS through an electronic portal in advance of filing the return on which the election is made. Each item of eligible credit property must be registered, and a transferability election will not be valid unless the pre-registration procedures have been followed and the registration number for the eligible credit property is properly included on the eligible taxpayer's return.

Key Points

- While a few surprises are found in the proposed regulations, the guidance generally provides sufficient certainty to allow tax credit transfers to take place. However, transfers are not valid without pre-registering a given credit-generating project and the IRS online portal for registration is not yet live. Taxpayers are allowed to reduce estimated tax payments for transfers expected to occur, so it is possible to begin realizing economic benefits from transfers today.

- Recapture risk for tax credits with recapture generally resides with the transferee, with two limited exceptions.

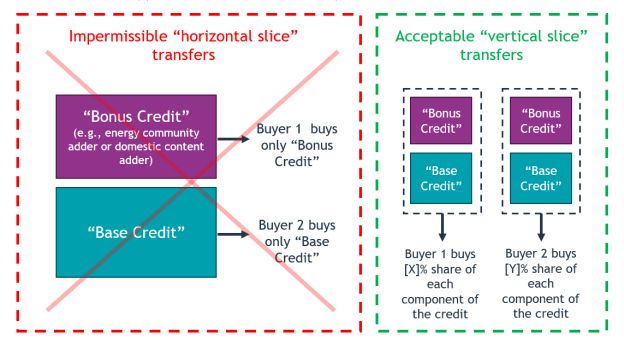

- Credits cannot be divided between "base" amounts, "added" or "bonus" amounts, or otherwise. Transfers must be a proportionate share of each transferred credit.

- Restrictions on the timing of cash transfers will effectively require cash advances for credits in future years to be structured as loans.

Which Tax Credits Are Eligible?

The following 11 green energy tax credits are eligible for the transferability election:

- Section 30C credit for alternative fuel refueling property

- Section 45 renewable energy (wind) production credit (PTC)

- Section 45Q carbon capture credit

- Section 45U zero-emission nuclear power production credit

- Section 45V clean hydrogen production credit

- Section 45X advanced manufacturing production credit

- Section 45Y clean electricity production credit

- Section 45Z clean fuel production credit

- Section 48 energy (solar) investment tax credit (ITC)

- Section 48C qualifying advanced energy project credit

- Section 48E clean electricity investment credit.

The general framework of transferable tax credits is fairly straightforward. Once a tax credit is generated, the taxpayer with whom the credit was determined can make an election to transfer that credit to another taxpayer. The consideration paid by the transferee must be in cash. The consideration is nondeductible to the transferee and not included in the income of the transferor. The new Tax Code 6418 statute does not provide too many rules otherwise, leaving important rules to the IRS.

The following are some of the highlights from the IRS rules that were released in these temporary and proposed regulations.

Splitting Credits and Secondary Transfers

While a taxpayer can choose to transfer all of the credit to a buyer, the proposed rules make it possible for a taxpayer to make multiple elections, effectively splitting up the credit and transferring portions of it to multiple transferees. But any transferred credit portion must reflect a proportionate share of an eligible credit. That is, you cannot transfer only the "bonus" portion or the "step-up" portion of the credit but must transfer a vertical slice of all components, including the base portion, of a credit. This eliminates the ability of the transferor to sell off less risky portions of the credit and retain the riskier portions as a structural transaction feature.

Note that when the eligible credit property is held by a passthrough entity, such as a partnership or S corporation, the transfer election is made at the entity level and the income associated with the transfer (which is treated as tax exempt) will be allocated among the partners or shareholders in accordance with their distributive shares of the otherwise eligible credit. The cash received by a transferor partnership can be distributed without restriction. The tax-exempt income can also be allocated to only those partners who wanted to sell their share of the credit if only some partners want to sell their share of credit while other partners do not.

Further, a credit portion may only be transferred once, meaning that the credit buyer (the transferee taxpayer) cannot then turn around and make its own transfer election with respect to the same credit. However, in the case of passthroughs, the partnership or S corporation that purchases credits can allocate the purchased credits to its direct or indirect owners without violating the no second transfer rule. Further, allocations of the purchased credits to partners of the transferee partnership are permitted with fairly generous discretion.

The regulations draw a distinction between "brokers" and "dealers," providing that brokering/syndicating of credit transfers is acceptable (because ownership does not transfer to the broker), whereas dealing in transferable credits (where the dealer is an intermediary buyer) would be prohibited under the no second transfer rule. There is not much in the regulations now, but perhaps there will be future guidance to help make this distinction more meaningful.

Finally, because the rules provide that the credit transferor must own the eligible credit property or conduct the qualifying activity itself in order to elect to transfer the credit. Thus, recipients of a Section 45Q credit by way of an election under Section 45Q(f)(3)(B) (carbon capture equipment owner elects to transfer the credit to the sequestering party) or of an ITC by way of a lease pass-through election pursuant to Section 50(d)(5) (lessor elections to transfer the credit to the lessee) will not be able to take advantage of the Section 6418 transferability election. The IRS seemed keen on preventing transfers in these situations notwithstanding that the no second transfer rule would not have prohibited these transfers. The IRS interpreted "determined with respect to such taxpayer" to require ownership of the underlying ITC property, an interpretation that is not an obvious or necessary result of the language in Section 6418. The Treasury could have easily arrived at a different interpretation so as to allow transfers in these situations. The guidance seeks to avoid confusion with sale leaseback transactions and includes language distinguishing sale leasebacks from lease pass-through transactions.

Cash Payments and No Tax on Discount

Eligible credits are transferable under Section 6418 only if the amounts paid by the transferee taxpayer in connection with the credit transfer are paid in cash during a specific time period that begins at the beginning of the year in which a credit is generated and ends on the extended due date of the filing of the tax return for that year.

The proposed regulations contain a safe harbor timing rule that provides certainty when it comes to the timing requirement (accounting for the requirement that a transfer election statement must be completed by both the transferor and the transferee before a return is filed by either party). Specifically, a payment will comply with the paid in cash requirement as long as it is made within the period beginning on the first day of the eligible taxpayer's taxable year during which a specified credit portion is determined and ending on the due date for completing a transfer election statement.

However, this rule has substantial implications with respect to PTC and PTC-like credits that are generated over a number of years. It is common for tax equity investors in PTC deals to contribute most of their cash shortly after commercial operations, with the expectation of generating a return based mostly on tax credits over the subsequent 10 years. Developers and investors would naturally seek to mimic this in tax credit transfer deals.

Assume, for example, that the tax credit buyer and seller agree that the buyer's money will be provided entirely shortly after placement in service of the asset so as to pay off construction financing. This rule regarding the timing of cash payments effectively requires this transaction to be structured as a loan. The tax credit buyer would need to provide most of that cash in the form of a loan to the extent related to credits to be generated in future years. Then as those credits are generated over time, the sponsor/project/borrower would repay the loan and the investor would use those debt service proceeds to purchase the credits generated in subsequent years. This would be the only way to make the overall initial transfer of cash non-taxable like it is today in a traditional tax equity structure.

While most of the large PTC transfer deals were already being structured to have debt-like features to protect the investor in the event of underperformance (e.g., security interests), this structure presents a new "debt vs. equity" aspect to the analysis. Tax credit investors and sponsors will need to be certain that the initial cash payment will be treated as debt and the overall structure will be respected. Further, this rule effectively mandates some portion of the credit generation to be taxable given that tax law will require the loan to have at least some minimum interest rate, but the use of the cash from debt service would go towards a non-deductible purchase of tax credits so there would be no offsetting deduction to the interest income.

In more favorable news, if a transferee buys a credit at a discount (pays less than the credit amount transferred), the proposed rules provide that there is no gross income to the transferee (and therefore no tax due as a result of the discount) under the so-called transferee gross income exclusion rule. Note that tax credit purchasers have flexibility in how they apply the transferred credits (which can be carried back three years).

When it comes to tax payments, the proposed regulations also helpfully provide that a transferee may take into account its purchased credit portion when calculating its estimated tax payments, even if the purchase has not yet occurred but is merely planned. Several banks are proposing products in which deferred payment requirements on the tax credit transferee are a selling point but the transferee still gets the benefit against estimated taxes. The benefit of these deferred payment features are now supported by the guidance.

At-Risk and Passive Activity Rules

The guidance seeks to maintain a conceptual distinction between (i) rules that relate to whether a credit is generated in the first instance and (ii) rules that relate to whether a credit can be utilized once generated.

In the category of rules relating to whether a credit is generated, the guidance states that both the at-risk rules (in Tax Code Section 49) and the tax-exempt ownership restrictions (recall that entities eligible for "direct pay" including tax exempt organizations are not able to take advantage of transferability) apply based on the tax attributes of the transferor taxpayer. Only an "eligible taxpayer" (any taxpayer not described in Section 6417(d)(1)(A)) can take advantage of transferability, meaning that tax-exempt organizations are generally ineligible. However, because the transfer election is made at the transferor entity level in the case of passthroughs, the existence of a tax-exempt partner will not disqualify the passthrough entity from being eligible to make the election.

Nevertheless, based on current guidance, there would be a haircut to the amount of the tax credit available for transfer by the partnership based on tax-exempt ownership. This seems potentially to have been an oversight when taken together with language in the Section 6417 "direct pay" proposed regulations.

The preamble to the Section 6417 "direct pay" proposed regulations (REG-101607-23) includes commentary by the Treasury regarding partnerships with tax-exempt partners, even partnerships in which every partner is a tax-exempt that would otherwise be eligible for direct pay. The preamble provides an explanation for why the proposed regulations under Section 6417 nevertheless disallow a direct pay election by such a partnership and includes a statement that such a partnership would be eligible to make a transfer election. Thus, one could take away the implication/intent by the Treasury that such partnerships are prohibited from direct pay but should still be able to transfer their credits.

However, the statute that turns off the rules against tax-exempt ownership only applies in the case of a direct pay election under Section 6417 and there is no corollary rule in Section 6418. On the contrary, the Section 6418 proposed regulations specifically provide that the anti-tax exempt rules with respect to the ITC are applicable in the context of Section 6418 transfers. Thus, while such partnerships are technically eligible to make a transfer election, only in a narrow set of circumstances would such a partnership have a credit to transfer (e.g., if all the allocations with respect to such partnership and each partner never change over the life of the partnership, which is an uncommon/unrealistic expectation). In situations in which the partners are comprised both of tax-exempts (or other entities eligible for direct pay) as well as other entities eligible for transferability, the entire credit would not be disallowed but the "haircut" for the tax exempt ownership would need to be quantified and taken into account.

Another unfavorable surprise in the proposed regulations is that Section 469 passive-activity rules apply at the transferee level and are especially restrictive. The guidance provides that any purchased credit be treated as automatically passive. Presumably, the IRS does not want to be having passive-activity arguments with taxpayers, but this is an especially harsh result.

Recapture and Excessive Credit

The proposed regulations also flesh out various rules designed to police potential abuse associated with the transferability feature. It is worth noting that the guidance explicitly states that sellers and buyers are free to contract for indemnification relating to tax credit transfers. The proposed regulations do not identify any restrictions as to what can be indemnified.

Generally, the transferee taxpayer bears the risk of adjustment of a transferred tax credit based on IRS audits related to the initial determination of credit value, such as whether prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements are satisfied, whether the project is located in an energy community, the basis of the credit-generating property for ITCs, and other issues relating to determining the amount of the credit in the first instance.

Further, to the extent a credit is subject to recapture, then the rules provide that the transferee (the credit purchaser) is generally liable for the credit recapture amount. For example, for ITC-generating solar projects, if the project is taken out of service during the five-year recapture period or "directly" sold by the transferor of the ITC, the transferee would bear the financial responsibility of recapture.

However, there are two circumstances in which the recapture liability is not borne by the transferee: (1) recaptures caused by "indirect" transfers of owners of a partnership (i.e., when a partner's interest in the partnership is reduced by more than one-third, this is normally deemed to be an "indirect" disposition of the ITC-generating property that triggers partial recapture) and (2) recaptures caused by an increase in nonqualified nonrecourse financing by partners in a partnership in the year following placement in service. In those two cases, recapture liability still applies but the partners that caused the issue retains liability for recapture rather than the transferee. This will be very helpful, for two reasons: first, as a diligence matter, transferors will not need to share their economic waterfalls and allocation structures, which are highly sensitive data, with transferees in order to get a transferee comfortable that there is no recapture; second, transferees do not need to rope in upper-tier partners of a transferor into covenants and indemnity agreements, thereby increasing transactional efficiency with respect to documentation and execution.

If the IRS determines that there's been an excessive credit transfer (that is, more than the amount of allowable credit was actually claimed by the transferee taxpayer), then the transferee taxpayer will generally be liable for the excess plus a 20% penalty. The risk with respect to the penalty does not appear to be limited to issues caused by the transfer of tax credits or any other specific issues. The example in the regulations is of a $100 credit that turns out to only be $50, and $80 of the $100 is transferred. The example does not provide the reason why the credit was reduced from $100 to $50, but says there is an excessive credit transfer because $80 was sought to be claimed by a transferee when only $50 was available. Thus, the reason for the recapture does not appear to factor into the analysis.

The proposed regulations provide that the 20% excessive credit transfer penalty does not apply if the transferee taxpayer can demonstrate that the excessive credit transfer resulted from reasonable cause, which is generally determined based on relevant facts and circumstances. A list of factors used to demonstrate reasonable cause is included in the regulations, the list is not exhaustive but includes reasonable reliance on third-party reports as a factor. Further, all transferees are considered a single transferee for measuring whether there's been an excessive credit transfer, which seems consistent with the rule requiring that each transferee to take a proportionate share of credits.

REITs

Finally, the rules generally provide that tax-exempt income received from tax credit transfers by a real estate investment trust (REIT) will not factor into the REIT's income tests. The rules specifically do not provide guidance on the REIT asset test and indicates the Treasury believes the guidance relating to the income test, which the guidance indicates should eliminate the risk of a prohibited transaction, is sufficient to allow REITs to mitigate risks with respect to the asset test as well. The Treasury has requested feedback specifically on these points.

Comments on REG-101610-23 are due by August 14, 2023. We encourage you to contact one of the below lawyers if you have questions regarding this IRS guidance.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.