Introduction

On February 6, 2014, the United States Patent and Trademark Office ("USPTO") announced a roundtable to solicit public opinions regarding the written description requirement ("WDR") as applied to US design patent applications ("DPAs") in "rare" situations ("Roundtable").1 The USPTO scheduled the Roundtable for the afternoon of March 5, and also requested written comments (due March 14).

The Roundtable responds what many design patent practitioners perceive as an unannounced shift to a heightened WDR standard for DPAs. This white paper introduces the WDR for DPAs, summarizes recent developments (including the Roundtable) and then assesses next steps.

The WDR for DPAs

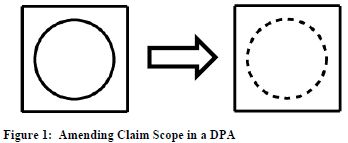

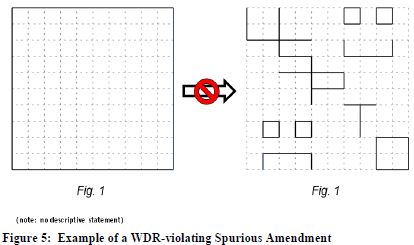

The legal basis for a WDR rejection is 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). Most DPA WDR rejections arise from (1) amending DPA claim scope (e.g., converting solid "claimed" lines to broken "unclaimed" lines) and/or (2) claiming priority to an earlier application (e.g., under 35 U.S.C. §§ 119 or 120). Here is an example of (1), amending claim scope in a DPA:

In the context of (2), claiming priority, a recent Federal Circuit case summarized DPA WDR law as follows:

The test for sufficiency of the written description, which is the same for either a design or a utility patent, has been expressed as 'whether the disclosure of the application relied upon reasonably conveys to those skilled in the art that the inventor had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date.' Ariad Pharm., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 94 USPQ2d 1161, 1172 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc). In the context of design patents, the drawings provide the written description of the invention. In re Daniels, 46 USPQ2d 1788 (Fed. Cir. 1998); In re Klein, 26 USPQ2d 1133 (Fed. Cir. 1993) ("[U]sual[ly] in design applications, there is no description other than the drawings."). Thus, when an issue of priority arises under § 120 in the context of design patent prosecution, one looks to the drawings of the earlier application for disclosure of the subject matter claimed in the later application. Daniels, 46 USPQ2d at 1789; see also Vas-Cath Inc. v. Mahurkar, 19 USPQ2d 1111 (Fed. Cir. 1991).2

A key DPA WDR issue is what "reasonably conveys" means, and therefore the extent of options to modify design patent claim scope from an initial disclosure.

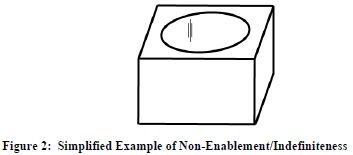

WDR rejections are one of two significant species of DPA rejections under 35 U.S.C. § 112.3 The other species, non-enablement/indefiniteness under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) and (b), typically arises from (1) unclear figures, such as when detail is too muddy or pixelated, or (2) figures in which the parameters of the detail cannot be discerned. Here is an example of (2):

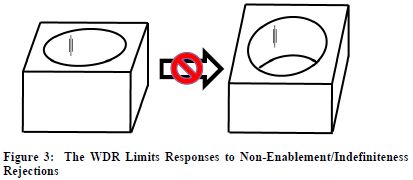

Assuming arguendo that the figure above is the full disclosure in the DPA, and that the three lines within the circle on the top surface correspond to shading (a common convention) to depict a hole in the cube, the DPA may be rejected as non-enabled/indefinite because the depth of the hole is not discernible. The WDR comes into play by limiting the responses available to overcome the non-enablement/indefiniteness rejection by amending the figures. Here, for example, if the applicant tried to overcome the rejection by, e.g., adding a second figure showing different perspective and the depth of the hole, a WDR rejection would likely result:

Thus, the WDR is very significant in DPAs because the majority of USPTO rejections are 112 rejections, and the WDR is directly or indirectly involved in most 112 rejections. Empirically, in an informal survey of the file histories of 1049 issued design patents, Professor Dennis Crouch found that 75% of all DPA rejections were 112 rejections (compared to 7% for rejections under 35 U.S.C. §§ 102 and 103).4

Design Day 2013 and a Perceived USPTO Policy Shift Regarding WDR Rejections

Each spring for more than seven years, the USPTO has welcomed the general public for "Design Day," co-sponsored by the American Intellectual Property Law Association ("AIPLA"), Intellectual Property Owners Association ("IPO"), American Bar Association and Industrial Designers Society of America ("IDSA").5 Design Day typically features presentations from USPTO employees and design practitioners.

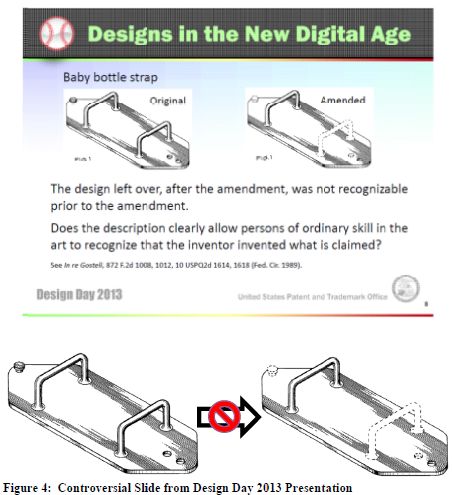

At Design Day 2013, a presentation by the USPTO Design Practice Specialist, Mr. Joel Sincavage, titled "More About the Written Description Requirement of 35 USC 112(a)" caused controversy. USPTO design patent examiners consult with Mr. Sincavage regarding, e.g., whether to make a WDR rejection. The controversy reached a crescendo with the following slide:

In a nutshell, Mr. Sincavage opined that if the claim scope were amended to disclaim the bar, nub and hole (i.e. go from left to right above), then a WDR rejection should be made.6

A heated Q&A period followed, with design patent practitioners responding (and some fuming and flailing) that the presentation defied years of USPTO practice (evidenced in the public prosecution histories of thousands of US design patents), and questioning the need for an abrupt policy shift (as well as a lack of transparency and proper procedure in making the shift).

Empirically, and even before Design Day 2013, the consensus of design patent practitioners has been that the WDR standard for DPAs has been heightened. Some design patent practitioners go so far as to assert that even rudimentary amendments of single features that were once entered without a second thought are now subject to WDR rejections. In this regard, it is also noted that the WDR standard for DPAs in the two-dimensional computer icon and graphical user interface ("GUI") area has long been more rigid than the general WDR standard for DPAs, although the perceived policy shift has moved the general WDR standard closer.7

The Roundtable on March 5

The Roundtable arose from the Design Day 2013 controversy.8 The USPTO conducted the Roundtable around a U-shaped table in the USPTO's Madison Auditorium. Four USPTO employees (including a brave Mr. Sincavage) and seven designated public presenters sat at the table:

- Mr. Paul Bowen (Partner, Nixon & Vanderhye)

- Ms. Tracy Durkin (Director, Sterne, Kessler, Goldstein & Fox)

- Mr. William Fryer (Professor Emeritus, University of Baltimore)

- Mr. David Gerk (Patent Attorney, USPTO Office of Policy and International Affairs);

- Mr. Brian Hanlon (USPTO Director of the Office of Patent Legal Administration); and

- Mr. Robert Katz (Principal Shareholder, Banner & Witcoff, Ltd.)

- Mr. Bob Olszewski (USPTO Director for Technology Center 2900 (the design examination unit));

- Mr. Perry Saidman (Principal, Saidman DesignLaw Group)

- Mr. Joel Sincavage (USPTO Design Practice Specialist, Technology Center 2900)

- Mr. Richard Stockton (Principal Shareholder, Banner & Witcoff, Ltd.)

- Mr. Cooper Woodring (Past President, IDSA)

Some other commenters also sat at the table, and approximately 40-50 other members of the public and USPTO employees were in the audience. The USPTO also webcast the Roundtable live.

Roundtable Topics in the Federal Register Notice

As stated previously, the Federal Register notice for the Roundtable sought public opinion regarding WDR in "certain limited situations" in which "only a subset of elements of the original disclosure are shown using solid lines in an amendment or in a continuation application."9 In this limited context, the bulk of the remainder of the notice sought public input regarding:

whether it would be useful for design examiners to consider any of the following factors in determining whether an amended/continuation design claim, which includes only a subset of the originally disclosed elements (no new elements are introduced that were not originally disclosed), satisfies the written description requirement. These factors would only be applied by design examiners in the rare situation where there is a question as to whether an amended/continuation design claim satisfies the written description requirement. The factors are as follows:

- The presence of a common theme among the subset of elements forming the newly identified design claim, such as a common appearance;

- the subset of elements forming the newly identified design claim share an operational and/or visual connection due to the nature of the particular article of manufacture (e.g., set of tail lights of an automobile);

- the subset of elements forming the newly identified design claim is a self- contained design within the original design;

- a fundamental relationship among the subset of elements forming the newly identified design claim is established by the context in which the elements appear; and/or

- the subset of elements forming the newly identified design claim gives the same overall impression as the original design claim.10

In the notice, the USPTO also sought public input regarding:

- "any additional factors, not listed above, that would be useful for design patent examiners to consider";

- "the potential advantages and/or disadvantages of using such a factors-based approach"; and

- "whether there are mechanisms applicants can use to demonstrate that they had possession of designs claimed in future amendments/continuation applications at the time their original applications were filed," such as "whether use of a descriptive statement in the originally-filed application (e.g., that specifically identifies different combinations of elements which respectively form additional designs) could be a meaningful way for applicants to demonstrate that they had possession of designs claimed in future amendments/ continuation applications."11

Actual Discussion at the Roundtable

Mr. Gerk emceed the Roundtable, and public presentations began after an introduction by Mr. Olszewski. Here is a quick summary of the public presentations in chronological order:

- Ms. Durkin: The current WDR standard defies longstanding USPTO practice; making WDR rejections in Ex Parte Quayle actions (where prosecution on the merits is closed and thus where applicants' ability to respond substantively is limited), is further unfair.

- Mr. Stockton, on behalf of AIPLA: If factors must be used in "rare situations", then "factor infusion" into everyday DPA practice must be avoided. Some ways to avoid "factor infusion" include placing the burden on the USPTO design examiner to establish a "rare situation," providing examples to applicants and examiners of amendments that satisfy WDR and revising the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure ("MPEP").

- Mr. Woodring: Noting that he was the only designer presenting at the Roundtable, stated that the factors do not track how a designer thinks, and also commented that the factors will creep into design patent litigation even when non-"rare situation" design patents are at issue.

- Mr. Bowen: Proposed having a grid system over DPA figures to establish written description support for amendments tracking the grid.

- Mr. Katz, on behalf of US Section of International Federation of Intellectual Property Attorneys (FICPI): Characterized prior case law invoking the WDR, including Racing Strollers v. TRI Industries,12 noting that if something is disclosed, then WDR is satisfied. Mr. Katz also asserted that the factors carve out a subset of previously acceptable WDR situations in violation of Federal Circuit precedent.

- Mr. Saidman: The current WDR standard for DPAs is inconsistent with utility patent application practice (example provided). The USPTO should move to a "reasonably identifiable" WDR standard for DPAs.

- Mr. Fryer: General comments in view of In re Daniels and other cases regarding the correct approach to the WDR.

No public presenters supported the factors, and the presentations (and subsequent comments) generally tilted toward objections to and inconsistencies with the heightened WDR standard overall (even in non-"rare situations").13 At one point, the USPTO was asked to identify the problem that led to the heightened WDR standard. Mr. Sincavage responded to the effect that it was not fair for applicants to be able to claim any conceivable subset of elements (e.g., a door handle and a headlight and a bumper from a solid-line disclosure of an entire car). Underlying this response is what appears to be a concern that the public should have fair notice of what it can and cannot do, especially when an amendable continuing application remains pending.

In this regard, design patent practitioners acknowledged that "gaming the system" with spurious amendments should not be allowed. While a longstanding generalized maxim of US design prosecution practice has been that solid lines may be converted to dotted lines and vice-versa, if the maxim was indeed this simple then it would be very easy to "game the system." On this point, Mr. Stockton's presentation included a spurious amendment example in which he asserted a WDR rejection would be proper:

The USPTO has suggested that spurious "gaming the system" amendments have already been attempted, and everybody seems to agree that they should not be allowed. However, disagreement begins to arise when "real world" examples such as the baby strap in Figure 4 supra are considered.

After the public presentations, there was a brief discussion regarding "real world" additional examples the USPTO provided.14 No public presenters asserted that the examples would violate the WDR.

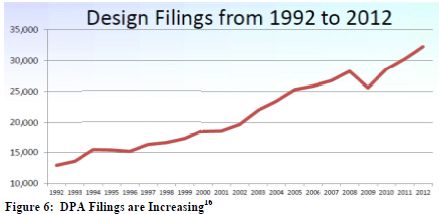

Another issue underlying the Roundtable is prosecution efficiency, for the USPTO and applicants. As a result of a heightened WDR standard, the USPTO stated that it is seeing an increase of DPAs with numerous embodiments (each corresponding, for example, to a potential claim scope that otherwise might be prohibited by the WDR if the claim scope were instead introduced by amendment) and/or lengthy descriptive statements describing various and sundry claim scopes that inventors possessed.15 These DPAs have the potential to dramatically decrease examination efficiency, especially in view of design examination fees being fixed, and an increase in DPA filings:

on the applicant side, obviously these DPAs are increasing attorney and drafting fees as well.17 Mr. Bowens' presentation showed an example of a more complex filing strategy (namely, using a grid system over DPA figures to establish written description support for any amendments that track the grid). This presentation probably caused some unease about prosecution efficiency, especially as no clear precedent exists to prohibit such a strategy.

To read this article in full, please click here.

Footnotes

1 See 79 Fed. Reg. 7171-73.

2 In re Owens, 106 USPQ2d 1248, 1250 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (emphasis added) (reh'g en banc denied). As discussed in the Post-Script infra, Owens is arguably limited to a narrow set of facts. But it remains the most recent Federal Circuit case relating to the WDR for DPAs.

3 The enablement requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) applies to DPAs but is generally an issue so long as all of the claimed subject matter is visible in the DPA.

4 See http://patentlyo.com/patent/2010/01/design-patent-rejections.html

5 See, e.g., http://www.aipla.org/learningcenter/Pages/2014-USPTO-Design-Day.aspx

6 In response to a question after his presentation, Mr. Sincabage opined that amending from right to left, i.e., from claiming a subset to claiming every element, would likely not trigger a WDR rejection.

7 In the GUI DPA context, and setting aside novelty, the amendment shown in Figure 1 likely would receive a WDR rejection. The amendment would be less likely to receive a WDR rejection if it were part of a set of figures relating to a cube having a punched-out cylinder as described previously.

8 See 79 Fed. Reg. at 7172 ("During discussions between the Office and members of the public attending Design Day, some attendees requested that the Office reconsider how the written description requirement under 35 U.S.C. 112(a) is applied to design applications where only a subset of elements of the original disclosure are shown using solid lines in an amendment or continuation application. In order to obtain a better understanding of the attendees' concerns, the Office is hosting this roundtable event.")

9 Id.

10 Id.

11 Id. at 7172-73.

12 Racing Strollers Inc. v. TRI Industries Inc., 11 USPQ2d 1300 (Fed. Cir. 1989)

13 One public commenter noted that the broadening reissue process allows conversion of solid lines to dotted lines in ways that seem inconsistent with the heightened WDR standard for DPAs.

14 See http://www.uspto.gov/patents/init_events/additional_ex_2014.pdf.

15 In the Federal Register notice, the USPTO sought comments regarding such descriptive statements. See 79 Fed. Reg. at 7173.

16 Extracted from Mr. Olszewski's presentation at Design Day 2013 titled "State of the Technology Center".

17 At the Roundtable, it was pointed out that this system will disadvantage smaller entities that lack resources to file DPAs with numerous embodiments and lengthy descriptive statements.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.