- within Technology, Criminal Law and Law Practice Management topic(s)

Traditional outsourcing agreements have been defined by charging on a time basis, with either hourly, weekly or monthly charges, or for defined outputs, where they are clear and unambiguous. Time based charges can be challenging to manage, with inefficiency incentivized through using a charging mechanism that provides more profit for more time spent delivering services. The use of automation in delivering services is enabling a new and different way of charging based on sharing measurable outcomes and sharing risk between the buyer and the supplier. This paper will explore options for charging, their pros and cons and how technology is enabling the transition to more sophisticated charging bases.

Secondly, for those companies with their own Global Capability Centers ('GCCs'), there is much debate as to whether pricing should be (i) with the objective of recovering the cost of operation from its users, (ii) with the objective of recovering the cost of operation plus a profit from its users or (iii) charging at rates that are used by third-party operators in the industry. Each of these options has advantages and disadvantages, but the most appropriate model for your company requires detailed consideration.

Alvarez & Marsal can help you to design charging mechanisms that incentivize performance, with shared risk and reward, especially leveraging technology solutions, and determine the optimal charging bases for your GCC operations.

Pricing bases are evolving towards shared risk, facilitated by technological advancements.

Pricing bases may be determined in three categories:

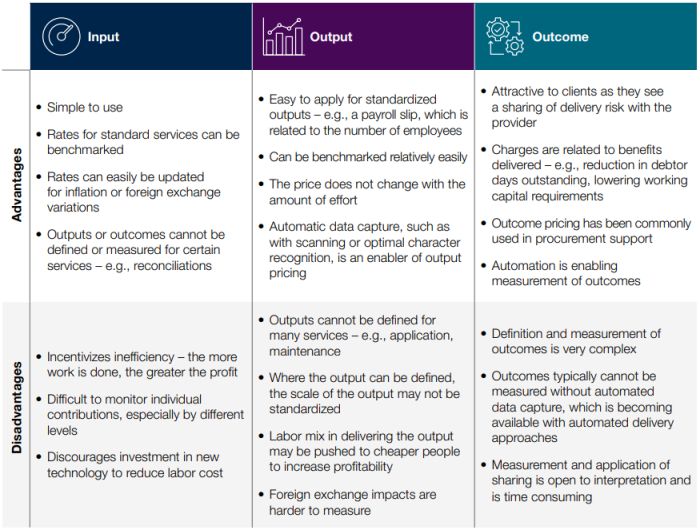

The table summarizes the three main bases of charging, which we then further describe throughout this paper

Three Charging Bases for Outsourced Contracts

Input-based pricing has been the most common approach over many years. Common examples are in application development, where a developer will charge at agreed hourly rates, which are often specified by level of person. Another example is in finance, with paying of invoices, or conducting reconciliations. These examples undoubtedly provide transparency of the amount of work and the level of person doing it but leave questions as to whether the right person delivered the work, whether the amount of time input was necessary and whether the work could be done more efficiently by applying technology in place of labor. This is especially true in this charging basis, as the supplier will decrease its revenue, even if it makes a 'one off' profit from implementing the new technology.

Output-based pricing has been common where the unit of output is standardized and well defined. Common examples include payroll slips, which can be related to the number of employees being paid and the format of the payroll report, or the invoices processed. The key to this approach is that the output being produced is standardized, consistent and well defined. In practice, this is not always possible, although advances in technology have helped speed up the process. In particular, electronic capture of data, through scanning or other means, has reduced the need for details to be manually input, thus saving time and effort, especially where large amounts of input have been required. In the example of an invoice, with electronic capture of the detail, the time to process a very simple or very complicated invoice becomes comparable, and charging per invoice is possible.

On the surface, output-based pricing appears to be simple, easy to manage and therefore attractive. However, things become challenging where there are changes in requirements, changes in volumes, changes in technology and foreign currency movements, each of which may result in a change of price per output. While such a price change may be fair, it can be very hard for the customer to validate the magnitude and timing of any change in the price of an output, and a process is required to confirm such adjustments.

Outcome-based pricing is far more complicated, and has been used much less frequently, due to its complexities. A good example of where outcome-based pricing has been used successfully is in the procurement space, where savings on purchases of goods and services through managing the process can be measured and shared between the customer and the provider. Savings are typically defined at the category level, as different categories of goods or services have different expected savings profiles. The key to successful sharing of savings is having in place rules for measurement of savings. While this sounds simple, it is in practice very complicated, especially to adjust for changes in volumes of goods or services, increases or decreases of commodities such as electricity or gas or foreign exchange fluctuations.

Another example can be seen in accounts payable and accounts receivable, whether through paying bills later or collecting cash earlier. In each case, the company's working capital is improved, and its cost of finance reduced. The challenge is measuring and calculating the benefits delivered. Traditionally, it has not been possible to measure such benefits, especially on a timely basis, and even where it has been possible to calculate benefit, the effort required has been too high relative to the benefit.

Automation, including artificial intelligence, has changed this, as benefits can be measured and calculated in real time. Moreover, the algorithm that is being used to measure the benefits can be easily updated as factors change. The ability to quantify benefit quickly allows benefit sharing to occur and has facilitated a move from traditional input and output pricing methodologies towards outcomes.

Originally Published 6 March 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.