A familiar feature of the Bankruptcy Code is the ability under § 365(d)(4) for the trustee or the chapter 11 debtor in possession (DIP) to assume (or assume and assign) or to reject an unexpired nonresidential real property lease. To assume, the trustee or DIP tenant must cure all defaults and provide adequate assurance of future performance1 as the price for continued occupancy of the premises.

Upon rejection, the trustee or DIP surrenders the property and is absolved from further obligations, while the landlord is authorized to file an unsecured proof of claim for damages suffered on account of termination of the lease.2 So the determination of the proper amount of those damages—the allowed amount of the landlord's claim—is a matter of gravity, for the estate and for the lessor.3

Here the Code does additional service for the debtor tenant's estate: It provides a "cap" on the allowable amount of the landlord's rejection-damage claim. Section 502(b)(6) provides that upon objection to such proof of claim, the court shall disallow the claim to the extent

(6)...such claim exceeds—

(A) the rent reserved by such lease, without acceleration, for the greater of one year, or 15 percent, not to exceed three years, of the remaining term of such lease, following the earlier of—

(i) the date of the filing of the petition; and

(ii) the date on which such lessor repossessed, or the lessee surrendered, the leased property; plus

(B) any unpaid rent due under such lease, without acceleration, on the earlier of such dates.4

Those provisions have occasioned numerous decisions in the books; precedents vary from district to district; and numerous claim-allowance points remain contestible. This article explores four means—additional to the normal task of drafting cogent prose for a proof of claim or a claim objection—for lawyering the client's desired claim amount in the allowance process, whether the client is the landlord or trustee or DIP tenant.

The term "lawyering" has skyrocketed into the vocabulary of lawyers, judges and scholars over the past 50 years. The author's definition is instrumental: "Lawyering" is the work of a lawyer who "invokes and manipulates, or advises about, the dispute-resolving or transaction-effectuating proc-esses of the legal system for the purpose of solving a problem or causing a desired change in, or preserving, the status quo" for a client.5

The essence of "lawyering" is, in short, finding a way to accomplish the desired result for the client, which requires innovation, resourcefulness and improvisation—sometimes beyond the usual techniques of courtroom advocacy and conference-room negotiations. This article posits the possibilities of lawyering landlord claims with flow charts, algebraic equations, algorithms and spreadsheets as creative means for explaining the function of § 502(b)(6) and advocating a particular desired result on behalf of clients on either side of lease-claim-allowance disputes in, or in anticipation of, bankruptcy cases, as well as in negotiations.

Lease-Rejection Claim-Allowance Process

Flow Chart

Bankruptcy judges have employed flow charts to understand and explain difficult Code provisions.6 Similarly, in a § 502(b)(6) dispute or negotiation, a flow chart can undergird an argument on a client's behalf by depicting at a glance the overall process of rejected-claim allowance. A flow chart may also explain to the client and demonstrate to the court and parties in a hearing the two distinct phases of the § 502(b)(6) analysis. The first phase is the determination of the landlord's damages, after rejection and lease termination; this is a function of applying the terms of the lease agreement under state law. The second phase is calculation and then application of the § 502(b)(6) cap to the amount of damages.

A flow chart illustrates that this Code subsection is not the measure of a landlord's damages but rather the limit on them (see Figure 1).7 Disputes may be identified and located at various points on either or both sides of the two-phase § 502(b)(6) process depicted in this flow chart.

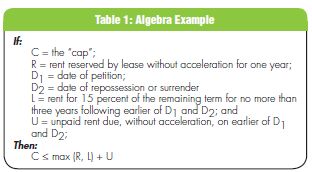

Algebra

Bankruptcy courts have occasionally used algebra to assist in analyzing the difficult provisions of the Code.8 Hence, algebra may aid in comprehending and explaining the formula of § 502(b)(6) (see Table 1).9 An algebraic expression of the cap may be informative to a math-minded client or financial adviser, as well as to a savvy judge.10

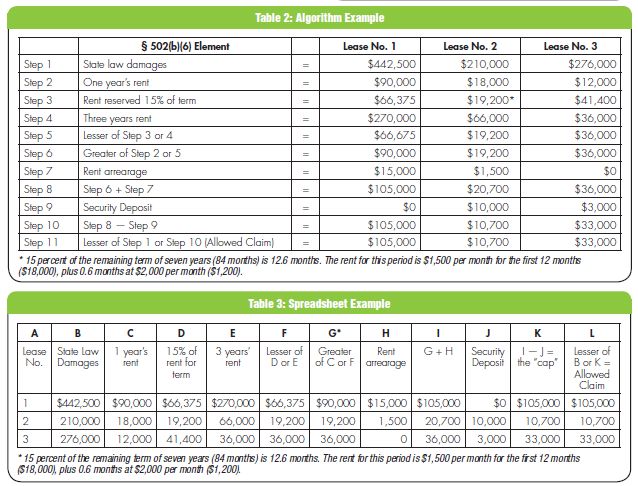

Algorithm

Widely used in computer programming, algorithms may be another way to understand and explain § 502(b) (6). Referenced in several bankruptcy decisions,11 an algorithm is simply a defined series of steps for a computation or operation (see Table 2).12 An algorithm may clarify the sequencing of the calculation and aid the arithmetical computation.

Spreadsheet

Examples of judges using, even creating, spreadsheets to assist decision-making exist in the case law,13 and parties have used spreadsheets in preferential-transfer litigation14 and as proof-of-claim attachments.15 Similarly, a spreadsheet may both calculate and display the application of the cap to lease-termination claims on multiple leases, as shown in Table 3.16 Applied to a lease portfolio, the spreadsheet demonstrates § 502(b)(6)'s benefit to the estate.

Conclusion

The rejected landlord's proper claim amount is easily subject to dispute. Both sides are normally represented by counsel, and their lawyering makes a difference. This article stimulates thinking about graphic and mathematical expressions17 or other nontraditional tools18—adapted for variations per local precedents—for creatively lawyering the desired result, whether the client is a landlord or trustee or DIP tenant. Counsel may employ these methodologies in pre-petition planning, out-of-court negotiations or post-petition contests regarding the landlord's allowable rejection-damage claim under all chapters of the Bankruptcy Code.

Reprinted with permission from the ABI Journal, Vol. XXXI, No. 11, December/January 2013.

Footnotes

1 11 U.S.C. § 365(b).

2 11 U.S.C. § 502(g).

3 This article assumes that the estate's distributable value makes the game worth the candle.

4 11 U.S.C. § 502(b)(6).

5 Josiah M. Daniel, III, "A Proposed Definition of the Term 'Lawyering,'" 101 Law Library J. 207, 215 (2009).

6 In re Gonzalez, 388 B.R. 292, 297, and Appendix A (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2008) (utilizing flow chart in chapter 13 to comprehend and apply § 1325(b)); In re Williams, 394 B.R. 550, 557 n.10 (Bankr. D. Colo. 2008); In re Singletary, 354 B.R. 455, 459, and Ex. A (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2006) ("[F]low chart of the mechanics of § 707(b)."); Boyd v. Water Doctor (In re Check Reporting Services Inc.), 140 B.R. 425, 444 (Bankr. W.D. Mich. 1992) (charting "ordering problem" of new-value exception under § 547); Gore v. IRS (In re Gore), 182 B.R. 293, 312 n.16 (Bankr. N.D. Ala. 1995) (flow chart in IRS publication, Your Rights as a Taxpayer, helps understand § 507(a)(7)(A)(i)).

7 The author thanks his partner, William L. Wallander (Vinson & Elkins LLP; Dallas), for flow chart assistance.

8 Crowson v. Zubrod (In re Crowson), 431 B.R. 484, 487 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2010) (algebra helps determine how much tax refund is estate's); In re Porter, 112 B.R. 979, 984 (Bankr. W.D. Mo. 1990) (section 522(f) is "more like a difficult algebra equation than purely legal analysis"); Slater v. Smith (In re Albion Disposal Inc.), 152 B.R. 794, 804 (Bankr. W.D.N.Y. 1993) ("If the value of the two parcels together is T and T is made up of two elements, O...and S...then fixing the value of S defines O.").

9 The author thanks Prof. Nan Bailey of the Mathematics Department at the University of Texas at Tyler for her algebraic assistance.

10 Other examples of algebra in decision-making: Woodson v. Tom Bell Leasing (In re Breece), 58 B.R. 379, 386, and n.5 (Bankr. N.D. Okla. 1986); GMAC v. Willis (In re Willis), 6 B.R. 555, 564-65 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 1980).

11 In re Predragovic, 2010 WL 3239360, at *3 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio Aug. 16, 2010) ("[M]eans test is...an algorithm that makes limited purpose calculations."); In re Spurgeon, 378 B.R. 197, 205-6 (Bankr. E.D. Tenn. 2007) (algorithms in interpreting § 1325(b)(2)); Child World Inc. v. Service Merchandise Co. (In re Child World Inc.), 173 BR 473, 476 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 1994) ("[F]ive elements of the preference algorithm.").

12 Using three hypotheticals, a simple algorithm for § 506(b)(6) may be:

" Lease No. 1: Remaining term of four years 11 months; remaining rent reserved of $442,500; monthly rent of $7,500; $15,000 rent arrearage; $0 security deposit.

" Lease No. 2: Remaining term of seven years; remaining rent reserved of $210,000; monthly rent of $1,500 for 12 months, then $2,000 for 24 months, and finally $3,000 for 48 months; $1,500 rent arrearage; $10,000 security deposit.

" Lease No. 3: Remaining term of 23 years; remaining rent reserved of $276,000; monthly rent of $1,000; $0 rent arrearage; $3,000 security deposit.

13 In re Heritage Organization LLC, 375 B.R. 230,260-61 (Bankr. N.D. Tex. 2007) (court "create[d] its own spreadsheet to track the numerous claims and defenses").

14 In re MarkAir Inc., 240 B.R. 581, 585 n.16 (Bankr. D. Ala. 1999).

15 E.g., In re DePugh, 409 B.R. 84, 109 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2009).

16 See footnote 12 for hypotheticals.

17 For instance, one court used "the simple set theory of middle-school mathematics" to aid decision-making. In re Coleman Enterprises Inc., 266 BR 423, 434 (Bankr. D. Minn. 2001).

18 See, e.g., Mark MacDonald, et al., "Chapter 11 as a Dynamic Evolutionary Learning Process in a Market with Fuzzy Values," 1993 Ann. Surv. Bankr. L. 1; Edward Adams, et al., "Beyond the Formalism Debate: Expert Reasoning, Fuzzy Logic and Complex Statutes," 52 Vand. L. Rev. 1243, 1245-46 (1999).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.