- within Compliance, Consumer Protection, Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- with readers working within the Business & Consumer Services and Construction & Engineering industries

To paraphrase Shakespeare, some are born to use telehealth, some learn to use telehealth, and some have telehealth thrust upon them.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly thrust telehealth onto all who had been reluctant to embrace it. The rapid and simultaneous expansion of coverage, available modalities, acceptance by providers, and use by patients will be one of COVID-19's lasting impacts on how health care is delivered. Seven months since the declaration of a public health emergency (PHE), several trends have developed that expose the risks associated with telehealth expansion and highlight how telehealth can improve health care delivery.

This Briefing identifies issues that health plans should address now in dealing with telehealth and offers predictions for how telehealth can best be utilized in the near future. The Briefing provides a brief overview of the status of telehealth pre-COVID-19, details key developments in telehealth as a response to the PHE and how those developments are shaping health plans' use of telehealth now, and concludes with a look ahead as telehealth becomes the preferred health care delivery model. Throughout the discussion, the Briefing focuses on two common threads, accessibility and technology, which characterize telehealth's development before COVID-19, make it a primary weapon in fighting the pandemic, and drive risks and opportunities moving forward.

Concepts and Status Pre-COVID

To understand the impact of COVID-19 on telehealth and what it means for the future, it helps to know the principal uses and modalities of telehealth before the PHE and how they were developing. For purposes of this Briefing, the term "telehealth" means the use of digital technologies to deliver medical care, health education, and public health services by connecting users in separate locations. The term "telemedicine" means the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient's clinical health status. Telehealth technology includes a variety of electronic modalities such as two-way video, smart phones, wireless tools and other forms of telecommunications technology. In this Briefing, we use telehealth to include the use of telemedicine unless otherwise specified.

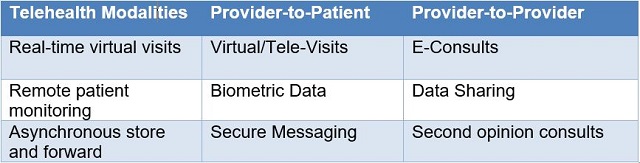

Telehealth is expressed through a variety of modalities that were becoming more ubiquitous even before COVID-19. Common modalities include: (1) synchronous, e.g., video conferencing, used for real-time patient-provider consultations, provider-to-provider discussions, and language translation services; (2) remote patient monitoring, where electronic devices transmit patient health information to health care providers; and (3) asynchronous (store and forward) technologies that electronically transmit pre-recorded messages, videos, and digital images, such as X-rays, video clips, and photos, between primary care providers and medical specialists. Examples of how these modalities can be used are set out in Table 1.

Table 1. Telehealth Modalities

More recently, mobile health applications have enabled use of health care information through mobile devices. In addition, telehealth users have leveraged virtual reality, robotics, and artificial intelligence to support diagnoses, chronic disease monitoring, and perform procedures.

These developments have been met with enthusiasm by state regulators. In its 2019 State of the States Report on Coverage and Reimbursement,2 the American Telemedicine Association (ATA) reported that 40 states and the District of Columbia adopted substantive policies or received funding to expand telehealth coverage since 2017. Among these policies, 36 states and the District of Columbia have parity policies for private pay coverage, and 16 mandate payment parity for private payers. With respect to modalities, only 16 states limit telehealth to synchronous technologies while most other states recognize remote patient monitoring and/or store and forward. The ATA also reported that the most common telehealth providers are physicians, mid-level practitioners, licensed mental health professionals, occupational therapists, physical therapists, psychologists, and dentists.

The states' enthusiasm for telehealth is based on the promise of greater access to health care with lower overall costs, which is made increasingly possible by advancements in technology. Greater access and improved technology also have made telehealth more attractive to a growing number of clinicians, patients, and payers. According to a survey of physicians reported by American Well in 2019, clinician adoption of telehealth increased by 340% since 2015.3 Likewise, a 2019 survey by Massachusetts General Hospital reported in the American Journal of Managed Care4 found that 79% of patients believed telehealth was more convenient for scheduling virtual video visits (VVV);5 74% reported the overall quality of the virtual visit was as good or better than an in-person visit; and 64% felt connected to the telehealth practitioner. Finally, according to a 2019 survey of large U.S. employers (over 500 employees) conducted by the National Business Group on Health (NBGH), 96% planned to offer telehealth coverage with their insurance in states where it was an allowed option.6

Advances in accessibility and technology also bring legal risk. For example, the lack of in-person interactions provides an opening for unscrupulous providers to claim reimbursement for services not provided. Telehealth advances also present new challenges in licensure and scope of practice including the validity of licensed services provided across state lines, the ability of mid-level providers to take on more active roles, and even artificial intelligence algorithms serving as the initial patient encounter and in care planning. These challenges go hand-in-hand with professional liability concerns, including whether virtual encounters expose professionals to a higher level of malpractice risk. In addition, the ubiquity of available technology dilutes privacy and security protections, especially when vendors in the telehealth information chain, including mobile app providers, do not qualify as "covered entities" under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Despite these concerns, telehealth experienced marked growth by the end of 2019. As the new decade began, telehealth was primed to advance into the mainstream of health care delivery. Then, everything changed.

How COVID-19 Accelerated Use of Telehealth

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a change in how health care services are delivered. Limiting exposure and virus spread while enabling increased access to vital services took top priority. In this environment, telehealth emerged as the optimal, and in some instances, exclusive, delivery model. Recognizing this, the U.S. government has issued an unprecedented array of temporary legislative and regulatory waivers and new rules to promote telehealth. The following are highlights of these efforts.

From a legislative perspective, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act)7 broke down many traditional barriers in the delivery of and payment for telehealth services. For example, Section 3701 of the CARES Act allows high deductible health plans (HDHPs) to waive an insured's deductible when receiving telehealth services, which alleviates the financial burden on the patient and encourages utilization. Section 3703 of the CARES Act eliminates the initial face-to-face requirement for telehealth services for Medicare, which unleashed access for those individuals who did not have a primary care provider or could not get a timely appointment because of the pandemic. For more specific applications, Section 3705 allows physicians to perform all home dialysis evaluations via telehealth, while Section 3706 allows physicians to use telehealth to recertify patients for hospice care.

Regulatory waivers followed suit. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) took a leading role in setting access and payment standards in the Medicare program that many private payers would follow. For example, CMS established payment for telehealth services at the same rate as in-person services; allowed beneficiaries to receive telehealth in any location, including their homes; and issued waivers allowing telehealth in treatment settings where it was previously unavailable, including emergency department visits, and physical, occupational, and speech therapy services.8

Likewise, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided guidance promoting telehealth as the preferred health care delivery model, both during and after the PHE, for a variety of non-COVID-19 care such as accessing primary care providers and specialists, including mental and behavioral health, for chronic health conditions and medication management; physical therapy, occupational therapy, and other modalities as a hybrid approach to in-person care; and remote monitoring of clinical signs of certain chronic medical conditions (e.g., blood pressure, blood glucose, other remote assessments).9

With respect to health information privacy and security, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) alleviated compliance obligations under HIPAA through enforcement discretion guidance on waiving penalties for good faith services provided through common technologies, such as FaceTime or Skype, during the PHE.10

This expansion of technologies and access, in terms of increased services, types of providers, and allowed locations, led to a dramatic increase in telehealth utilization. For example, CMS reported that in the first three months of the PHE, over 9 million Medicare beneficiaries received telehealth services.11 Of these, over 3 million received telehealth services over the telephone, which was not available before the PHE.12 Of note, CMS reported a higher percentage of utilization in urban areas, 30%, than rural, 22%, bucking the traditional notion that telehealth is better suited for rural communities.13

While utilization numbers have dipped, they still remain high compared to pre-pandemic levels. Patient satisfaction also remains high with McKinsey & Company reporting in September that responding telehealth patients had moderate to high satisfaction levels of 98%, although fewer were highly satisfied than in June or July.14

Legal Challenges and Opportunities Arising Out of the COVID-19 Telehealth Expansion

The marked expansion in telehealth utilization has raised numerous legal issues. This Briefing focuses on issues related to fraud, waste, and abuse; licensure and scope of practice; and information privacy and security.

Fraud, Waste, and Abuse

Fraud, waste, and abuse in telehealth comes in many forms. As the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) stated when CMS issued the telehealth waivers, "[t]here are unscrupulous providers out there, and they have much greater reach with telehealth, . . . Just a few can do a whole lot of damage."15 These concerns are equally borne by private health plans. In the seven months since the waivers went into effect, federal law enforcement has been active in rooting out fraudulent telehealth practices. These enforcement efforts provide a guide to suspicious patterns and trends health plans should be following now.

In the Middle District of Florida, the owner and manager of a durable medical equipment (DME) company were charged in connection with a scheme that used a telemarketing operation to collect the personal information of Medicare beneficiaries, purchase doctor's orders for orthotic braces for the beneficiaries under the guise of telehealth, and then submit more than $25 million in claims to Medicare for medically unnecessary braces.16 Similarly, in the District of New Jersey, laboratory owners were charged with submitting claims to Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies for genetic testing that the owners knew was medically unnecessary and not reimbursable. Many of the unnecessary tests were approved by doctors operating on telehealth platforms, who had not previously treated the patients and had little or no contact with them in connection with prescribing the testing.17

These cases show how accessibility can be abused when physicians use telehealth platforms to order diagnostics and supplies for patients they never see. As noted by the OIG, telehealth technology brings a scalability to these schemes, which generates more false claims than can be made through a traditional in-person practice. This scalability was evident in a similar scheme in Texas, which collected $2.9 million in approximately eight months.18

These fraudulent schemes existed before the pandemic and related telehealth waivers, but with more types of modalities, clinicians, and settings allowed, these schemes are likely to proliferate in the current environment. Health plans can take action now to mitigate this increased risk of fraud, waste, and abuse. The first line of action is beneficiary education. Many of the practices currently being prosecuted began with telephone or social media outreach to gain the beneficiaries personal information. Using these same pathways and traditional modes of communication, health plans can advise beneficiaries to be on the lookout for fraudulent schemes and let them know the hallmarks of such practices.

The second proposed course of action is identifying high-risk areas and utilizing heightened investigation efforts. Out-of-network providers in high-risk services such as laboratory, diagnostic testing, and DME have higher incidences of abuse just as they do in traditional delivery models. A third area of focus should be on identifying what's new, including new types of services and technologies that may now be covered as a result of the pandemic. Closer scrutiny in these new frontiers of telemedicine can help lower rates of fraud, waste, and abuse. Fourth, the adoption of legally compliant fail-safes that link coverage to documentation and other verification requirements also may be a useful tool. These requirements can be introduced in newly allowable services and rolled out after proof of efficacy. Finally, all health plan efforts in this regard should leverage technology for the collection and use claims data to identify trends and build criteria, which can flag a potentially fraudulent claim before the issue gets out of hand.

Licensure and Scope of Practice

The practitioner/patient relationship is protected in varying degrees in all 50 states. This protection includes states setting minimum standards for licensure and limiting the scope of a licensed professional's practice by their education and training. Telehealth disrupted this framework long before the PHE with several states adopting special telemedicine licenses, which allowed a patient at an originating site in one state to receive telemedicine services from a physician at a distant site in another state. This disruption was accelerated following the declaration of the PHE as demand for health care providers led multiple states to waive licensing requirements for out-of-state providers for both in-person and telehealth services. Likewise, state regulations relaxed boundaries between traditional physician functions and those of a mid-level practitioner such as an advanced practice nurse.19

As demand subsides, the increased supply of health care providers created by the pandemic has the potential to lower costs if PHE waivers on licensure and scope of practice remain in place. Downward pressure on costs would be increased where mid-level practitioners provide more services traditionally reserved to physicians.

Whether and to what extent these waivers remain in place will likely vary from state to state. There are, however, two guiding legal principles that should provide some level of predictability: the corporate practice of medicine doctrine and fee-splitting. How a state traditionally handles these issues, along with its local health care access issues and technological capabilities, will provide a good idea on whether the state will continue to allow telehealth services delivered by out-of-state physicians and mid-level providers.

Although related, the prohibitions on the corporate practice of medicine and fee-splitting are not interchangeable. The corporate practice of medicine doctrine generally relates to preventing a non-physician from controlling the clinical decisions of a physician.20 Fee-splitting, on the other hand, generally relates to a non-physician receiving a direct financial benefit from the physician's license, such as a percentage of fees received for physician services.21 In this context, some states take a transactional approach prohibiting ownership of physician practices and/or employment of physicians by non-physicians,22 while others take an operational approach, which focuses less on the legal relationship between the parties and more on whether the physician's independent medical judgment is protected.23

Understanding a state's corporate practice of medicine and fee-splitting prohibitions will be important for health plans seeking to use telehealth for the delivery of physician services across state lines. For example, states with no corporate practice of medicine or fee-splitting restrictions are more likely to allow out-of-state physicians to deliver telemedicine services to their residents. This is especially true if the employment agreement imposes quality guidelines consistent with the state's medical board standards.

Health plans also will need to assess patient safety. Traditional concerns regarding the clinical efficacy of telehealth as compared to in-person services will be compounded by concerns that the telemedicine encounter is being delivered by a physician who is not directly accountable to the state's licensing board. Similar safety concerns apply to expansion in scopes of practice for non-physician practitioners.

Health plans can address these issues though development of quality and outcome data. Long-term telehealth outcomes, with respect to both interstate services and expanded scopes of practice, that are equivalent to or better than historical numbers for in-person services can support transition to new telehealth delivery models. This will be especially the case if such outcome data is derived from larger patient populations driven by increased access. As with fraud, waste, and abuse, leveraging technology to capture and utilize data will be an important driver of this legal issue moving forward.

Health Information Privacy and Security

Privacy and security requirements under HIPAA and state law have historically been an obstacle to the quick adoption of telehealth. First implemented before widespread availability of wireless internet connectivity and smart phones, HIPAA's privacy and security rules are often cumbersome and confounding to practitioners and patients alike. At the same time, however, protection of personal privacy in a digital world was on the rise before COVID-19.24 HHS and OCR's response to the PHE, including HIPAA enforcement discretion guidance, both generally and with respect to non-traditional telehealth technologies, tended to deemphasize individual privacy in favor of ease-of-access, public health, and allowing providers to operate in emergency mode without fear of regulatory reprisal. With respect to telehealth, non-traditional technologies which came into use after OCR's announcement, e.g., Skype, Zoom, arguably do not carry the same privacy protections and certifications as traditional telehealth modalities.

Early reports from patients were in favor of the convenience of telehealth with no complaints about quality of care.25 Patient satisfaction, coupled with providers enjoying a lower regulatory compliance burden, may prove a high hurdle in returning health information privacy and security to pre-pandemic standards. That said, health plans are themselves covered entities under HIPAA and must develop a compliance strategy that takes into account alternative enforcement scenarios.

In this regard, two guiding principles emerge. First, even if the current enforcement discretion becomes the new norm, this enforcement discretion is limited to good faith uses of telehealth technologies. As the exigencies of the pandemic subside, good faith will evolve from ensuring access to ensuring safe, reliable access with due regard for information privacy and security. Health plans must work toward a balance in this regard, which will require careful consideration in authorizing non-traditional telehealth technologies.

Second, a health plan's current health information supply chain may include vendors who are not covered by HIPAA, or at least do not consider themselves to be. Now is the time for plans to examine this chain, identify weak links with respect to HIPAA compliance, and bolster those links with appropriate safeguards. These safeguards may include appropriate business associate agreements or technical measures to secure protected health information.

The likely result of COVID-19 on health information security and privacy will be to mark an historic shift in priorities from an asymmetrical emphasis on individual privacy to a more balanced approach, which gives equal consideration to concerns of public health, access, and convenience. Until that picture becomes clear, however, health plans should continue working toward optimal protection of the privacy and security of health care data.

Predictions and Conclusion

Telehealth will continue to be a preferred means of health care delivery in the future. The common threads of increased access and improved technology will remain high priorities in the immediate aftermath of the PHE such that a complete return to pre-COVID-19 standards is unlikely. Most practitioners will be able to continue to provide clinical services using telehealth technology. Likewise, laws and regulations will retain certain telehealth-friendly aspects of the temporary measures implemented during the early phases of the pandemic.

As such, the legal challenges that have arisen to date will continue but their trajectory will depend on what health plans do now in response. By identifying the legal risks applicable to the health plan and using data captured through telehealth services, health plans can take a leading role in identifying fraudulent patterns of behavior as well as tracking quality outcomes and patient safety. Privacy and security risks will remain, but enforcement standards will continue to be flexible within the bounds of good faith.

Now, as before the PHE, telehealth presents tremendous opportunity and risk. For a health plan to deploy a telehealth strategy properly in a post-pandemic environment, understanding the common threads of accessibility and technology is key. This requires an appropriate understanding of how these factors are shaping what's happening now and how to use them to overcome challenges and mitigate risks.

Footnotes

1 Twelfth Night, Act II, Scene V. William Shakespeare.

2 American Telemedicine Ass'n, 2019 State of the States Report: Coverage and Reimbursement, https://www.americantelemed.org/industry-news/annual-telehealth-state-of-the-states-report-from-ata-recognition-policy-and-reimbursement-vary-widely-2/.

3 American Well, Telehealth Index: 2019 Physician Survey, https://static.americanwell.com/app/uploads/2019/04/American-Well-Telehealth-Index-2019-Physician-Survey.pdf.

4 Donelan, et al., Patient and Clinician Experiences With Telehealth for Patient Follow-up Care, 25 Am. J. Manag. Care. 40-44 (2019).

5 The modality used in the study was 2-way audiovisual synchronous videoconferencing between the clinician and patient.

6 As reported in, Wheel Health Team, Master Guide to Telehealth Statistics for 2019 (July 31, 2019), https://www.wheel.com/blog/master-guide-to-telehealth-statistics-for-2019/.

7 Pub. L. No. 116-136.

8 See comments of CMS Administrator Seema Verma, reported in Early Impact Of CMS Expansion Of Medicare Telehealth During COVID-19, Health Affairs Blog (July 15, 2020), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200715.454789/full/.

9 CDC, Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html.

10 OCR, Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency (Mar. 30, 2020), https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html.

11 See CMS Administrator Seema Verma comments, supra note 8.

12 Id.

13 Id.

14 McKinsey Consumer Healthcare Insights, September 17, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/helping-us-healthcare-stakeholders-understand-the-human-side-of-the-covid-19-crisis.

15 Fred Schulte, Coronavirus Fuels Explosive Growth In Telehealth―And Concern About Fraud, Kaiser Health News (Apr. 22, 2020) (quoting Mike Cohen, operations officer with the OIG), https://khn.org/news/coronavirus-fuels-explosive-growth-in-telehealth-―-and-concern-about-fraud/.

16 See Department of Justice, 2020 National Health Care Fraud and Opioid Takedown: Case Descriptions, https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/hcf-2020-takedown/case-descriptions.

17 Id.

18 Id.

19 See, e.g., emergency amendments to Texas Board of Nursing regulations allowing an advanced practice registered nurse to treat chronic pain with scheduled drugs through use of telehealth medical services under certain circumstances including a determination that the telehealth treatment is needed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

20 See, e.g., Gupta v. Eastern Idaho Tumor Inst., Inc., 140 S.W.3d 747 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2004, pet. denied) (collecting cases); see also People v. Superior Court (Cardillo), 218 Cal.App.4th 492, 498 [160 Cal.Rptr.3d 264] (2013).

21 See, e.g., Flynn Bros., Inc. v. First Med. Assocs., 715 S.W.2d 782, 785 (Tex. App.-Dallas 1986, writ ref'd n.r.e.); see also Ten. Code Ann. § 63-6-225.

22 See Flynn Bros., Inc., 715 S.W.2d at 785; see also N.J. Admin. Code § 13:35-6.16.

23 See, e.g., Mack v. Saars, 150 Conn. 290, 188 A.2d 863 (1963); Virginia Board of Medicine, Guidance Document 85-21 (1995; Reaffirmed Oct. 18, 2018).

24 See, e.g., California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.100, et seq.

25 See supra note 4.

Originally Published by American Health Law Association