- within Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- within Law Department Performance and Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring topic(s)

The federal government is the largest buyer of products and services in the world—yet agencies often struggle to realize the full value from these purchases. Outcome-based contracting is possible under current federal rules, but agencies must improve contract planning and contractor performance management to achieve these objectives.

The Current State of Federal Procurement

The Federal Government spent approximately $755 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2024 on goods and services1 ranging from office supplies to aircraft carriers. Approaches to contracting vary widely across agencies and depend heavily on the type of product or service being procured.

The current administration is focused on shifting the government's buying approach toward paying for outcomes rather than for time or effort—a direction supported by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Multiple GAO studies2 demonstrate that outcome-based contracts would realize significant savings and improve operational performance. Outcome-based contracting has been available to and used by federal agencies for decades, but agencies often fail to fully utilize these tools to enforce performance standards and hold contractors accountable for delivering contractually required outcomes. Applying evidence-based practices more consistently could generate substantial benefits across the federal government.

Federal contractors seek higher profits, while agencies aim to maximize taxpayer value. Despite existing structures to achieve both goals, the government struggles to implement and execute effective mechanisms.

Misaligned Incentives

The issue is that federal contractors want to increase revenue and profitability, while government agencies want to improve return on taxpayer dollars for contracted services. While the structures exist to achieve both goals, the federal government has struggled to implement the appropriate mechanisms to achieve it and/or execute on proven mechanisms to extract value.

Federal contractors pursue increased revenue and profitability through multiple avenues. While securing new contracts is a common and obvious strategy, another approach lies in maximizing billable hours under time-and-materials (T&M) and cost-type contracts. As long as contractual requirements are met within the bounds of the contract—where employees are engaged in advancing the client's mission and work remains within the agreed-upon scope— such practices are legal and permissible. In practice, however, this dynamic can pressure contractor management and staff to prioritize billable hours at the expense of achieving meaningful outcomes for the client.

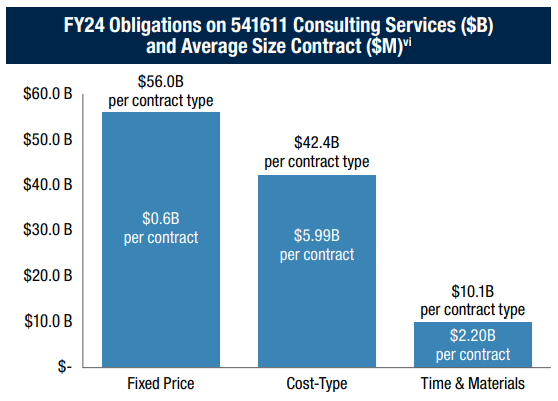

Agencies continue to use T&M and cost-type contracts, even when the services and products to be delivered can be reasonably estimated. For example, almost 50% of all consulting engagements with the US government in 2024 were contracted through T&M and cost-type methods. Likely reasons for persistent reliance include:

- A lack of understanding of contractor incentives and risk tolerance

- Reliance on contract types and structures with which procurement officials are familiar

- Reuse of prior requests for proposals (RFP), even when the requirement has matured or can now be accurately scoped

- A misconception that the government will save money through transparency in all pricing aspects

- Miscalculation of the risk profile for a given program

T&M and cost-type contracts may have a legitimate place in certain parts of the federal system—particularly for research and development, early-stage technology development, large IT modernization, complex systems integration, and undefined audit services. However, when the level of effort can be reasonably estimated, agencies should default to firm-fixed-price and fixed-price-incentive type contracts. These contract structures tie payment to clearly defined deliverables and performance standards, ensuring the cost of rework for any less-than-desirable work product is solely borne by the contractor, not the government, and that taxpayer funds are spent on results, not time.

Agencies should default to firm-fixed-price and fixed-price-incentive contracts when contractor effort is predictable. These structures ensure payments are tied to clear deliverables, holding contractors accountable for rework costs and focusing taxpayer funds on results, not time.

Aligning Incentives: Exceptional Performance and Cost Savings

Fixed Price Incentive Fee (FPIF) contracts offer a valuable solution to the issue described. Under the FPIF structure, the contractor's profit increases when work is delivered below target cost, ahead of schedule, or beyond performance minimums, while also placing risk on the contractor for significant cost overruns.3 Due to this risk-reward dichotomy, the FPIF is one of the more complex contract types to negotiate and execute, but is a meaningful tool to achieve outcome-based contracting objectives and reduce risk to the government.4

FPIF contracts provide another good option for outcome-based contracting that will provide a fair and reasonable incentive and a ceiling that provides for the contractor to assume an acceptable share of the risk. FPIF is often ideal for product development when there is opportunity for the contractor to gain efficiency savings through scale and when the government is seeking to gain a share of those savings. Conversely, FPIF is less appropriate when the government seeks long-term contractor investment in performance-enhancing capabilities. In all cases, success depends on clear metrics, disciplined program management, and balanced incentives.

Charting the Path Forward

The government has a tremendous opportunity to rethink how it structures and manages contracts to increase accountability, realize quality outcomes, and maximize taxpayer value. Too often, contractors are not held accountable for failing to deliver on contractual requirements or for delivering substandard work. In many cases, the government "checks the box" that the contractor has delivered on a given contractual requirement, pays the invoice, and moves on to the next deliverable or outcome required by the contract. This passiveness needs to change to truly deliver performance-based outcome contracting. Simply delivering a specification is not enough. The contractor must deliver and must deliver to an acceptable quality or outcome level.

Encouraging government agencies to use fixed-price-type contracts does not require massive legal, regulatory, or policy changes. The mechanisms already exist. Agencies must adapt to emphasize contractor accountability for performance when designing contracts and improve the accurate reporting of contractor performance. Agencies should change policies and regulations to require the use of fixed-price and incentive contracts unless a compelling reason exists to justify use of other contract types. Additional training for contracting officers to develop standardized contract language, evaluation templates, and incentive structures may also make fixed-price contracts easier to implement. Transitioning to fixed-price contracts, where possible, will save taxpayers billions of dollars each year,5 even if improvements are modest, and will align incentives between government and industry in achieving agency missions.

Footnotes

1 "Federal Contracting," U.S. Government Accountability Office, accessed October 21, 2025.

2 "Federal Contracting: Opportunities Exist to Reduce Use of Time-And-Materials Contracts," U.S. Government Accountability Office, June 7, 2022.

3 Cost overruns that do not exceed the point of total assumption (PTA) are shared with the government based on the agreed-upon allocations.

4 "Fixed Price Incentive Firm Target (FPIF) Contract Type," Defense Acquisition University (DAU), updated October 21, 2025.

5 "S. Rept. 118-274 - IMPROVING CONTRACTING OUTCOMES ACT OF 2024," Congress.gov, accessed October 21, 2025.

6 Chart is created using data obtained through advanced search at www.usaspending.gov.

Originally published on 04 November, 2025

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.