- within Compliance topic(s)

In this article, the author reviews the basic elements of the False Claims Act, its qui tam provisions, recent Department of Justice enforcement statistics and a number of recent False Claims Act developments.

The civil False Claims Act (FCA)1 was enacted in 1863 in response to allegations of fraud in Civil War procurements. The FCA has since become the government's weapon of choice to combat fraud, waste, and abuse in government contracting. This article begins by briefly reviewing the basic elements of the FCA and its qui tam provisions, and recent Department of Justice (DOJ) enforcement statistics. This article then discusses a number of FCA developments, including:

- The Supreme Court's actions regarding the government's authority to dismiss qui tam actions under 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A), and the correct pleading standard required to prove scienter;

- The Supreme Court's refusal to engage on the controversial issue of the FCA's pleading with "particularity standard";

- More changes in DOJ's enforcement policy under the Biden Administration;

- Status of Senator Chuck Grassley's proposed amendments to the FCA;

- Growing FCA enforcement against private equity firms; and

- Ongoing priority FCA enforcement against COVID-19 pandemic relief fraud.

I. BASIC ELEMENTS OF THE FCA AND QUI TAM PROVISIONS

The FCA makes it unlawful for a person to knowingly: (1) present or cause to be presented to the government a false or fraudulent claim for payment, or (2) make or use a false record or statement that is material to a claim for payment.2 A person acts "knowingly" under the FCA if he or she acts with "actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of information."3 Mistakes and ordinary negligence, however, are not actionable under the FCA.4

As of January 30, 2023, the FCA provides for up to treble damages and penalties of between $13,508 and $27,018 per violation. Violators are also subject to administrative sanctions, including suspension or debarment from participating in government contracts. The FCA has a lengthy statute of limitations of no less than six years and, in some cases, up to 10 years after a violation has been committed.

The FCA permits private citizens, known as qui tam relators, to bring cases on behalf of the government. In qui tam cases, the complaint and a written disclosure of all relevant evidence known to the relator must be served on the U.S. Attorney for the judicial district of the court where the case was filed as well as on the U.S. Attorney General. The qui tam complaint is then ordered sealed for a period of at least 60 days, and the government is required to investigate the allegations contained therein and decide whether to intervene. If the government declines to intervene, the relator may proceed with the complaint on behalf of the government. The complaint must be kept confidential and is not served on the defendant until the seal is lifted.

Relators may receive a "whistleblower bounty" of between 15 and 25 percent of the recovery if the government intervenes in their cases and between 25 and 30 percent if the government declines.

II. DOJ REPORTS HUNDREDS OF NEW FCA CASES AND BILLIONS OF DOLLARS IN RECOVERIES

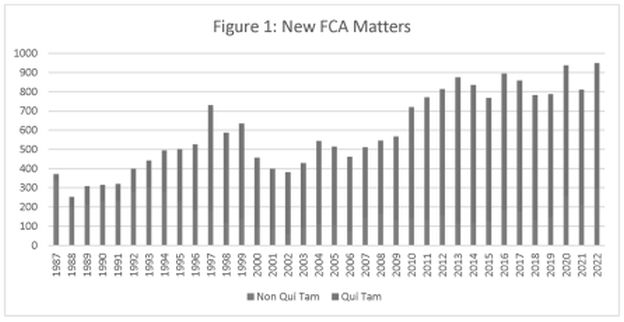

Figure 1 charts new FCA cases per year, which show a steady increase in qui tam-driven cases.5 Well over 700 FCA cases have been filed each year for the past 13 years and a high percent of those cases have been qui tam cases. Many qui tam cases remain under seal for years pending the DOJ's intervention decision. In 2022, there was a high-water mark in new FCA cases brought by both the government and qui tam relators for a total of 948, likely linked to the expenditure of substantial federal funds and potential for pandemic relief fraud. This uptick started back in 2020 during the beginning of the COVID-19 DOJ Office of Public Affairs, Fraud Statistics—Overview (February 7, 2023).

The DOJ collected over $2.2 billion in settlements and judgments in 2022, a substantial step back from prior years when there were more individual big settlements. In 2022, however, the 351 settlements and judgments reported by DOJ represents the second highest number in a single year since the FCA amendments in 1986. Figure 2 shows annual recoveries by the government in FCA cases and compares recoveries coming from qui tam cases where the government declined to intervene versus non-qui tam cases or qui tam cases where the government intervened.6 Historically, the bulk of the recoveries came in non-qui tam cases and qui tam cases where the government intervened. There was an anomaly in 2022 when recoveries from qui tam cases outpaced those in which the government actively participated. Consistent with recent trends, DOJ reported recoveries ($1.7 billion) in 2022 mostly came from settlements and judgments from the health care industry, including drug and medical device manufacturers, durable medical equipment, home health and managed care providers, hospitals, pharmacies, hospice organizations, and physicians. DOJ reported that additional 2022 recoveries reflected its focused attention on new enforcement priorities, including in pandemic relief programs and alleged violations of cybersecurity requirements in government contracts and grants.

Footnote

1. 31 U.S.C. § 3729 et seq

2. 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729(a)(1)(A)–(B) (2009); U.S. ex rel. Rose v. Stephens Inst., 909 F.3d 1012, 1017 (9th Cir. 2018).

3. 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)

4. U.S. v. Science Applications Int'l Corp., 626 F.3d 1257 653 F. Supp. 2d 87 (D.D.C. 2009).

5. DOJ Office of Public Affairs, Fraud Statistics—Overview (February 7, 2023).

6. See footnote 1 above.

Click here to continue reading . . .

Originally published by LexisNexis.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.