- within Finance and Banking topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- within Transport and Cannabis & Hemp topic(s)

The umbrella partnership real estate investment trust (UPREIT) structure has been a cornerstone of the modern REIT industry since its introduction in 1992. For property owners, the UPREIT structure provides a path to contributing appreciated real estate in tax-deferred transactions to a REIT's operating partnership in exchange for operating partnership units (OP units), instead of cash or taxable REIT stock. As holders of OP units, property owners gain access to the diversity and liquidity unique to the public trading markets, a combination that offers significant advantages to alternatives such as like-kind exchanges under Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code. For REITs, the OP unit exchange structure provides the means of using the REIT's equity (in the form of the OP unit) as an acquisition currency, while giving the REIT a competitive edge compared to all-cash buyers as a result of the tax deferral.

The UPREIT structure has proven flexible and is used today by sophisticated practitioners in a number of additional ways that help facilitate tax favorable transactions and executive compensation programs across the REIT sector.

Goodwin is proud to have served as special tax counsel in connection with the creation of the industry's first public UPREIT structure in the Taubman Centers 1992 IPO. This article provides a detailed overview of the OP unit transaction structure, highlighting key tax considerations, corporate governance mechanics, securities law matters, and protective measures typically sought by contributors.

This article does not contain a complete discussion of tax considerations relevant to a potential contributor or to the UPREIT and should not be considered tax advice. This article does not address any tax considerations other than U.S. federal income tax considerations and does not address tax considerations for contributors that are not U.S. persons. All parties are strongly advised to consult with their tax advisors regarding the potential tax consequences of contributing property in exchange for OP units, based on their individual circumstances.

I. Basics of the OP Unit Transaction Structure

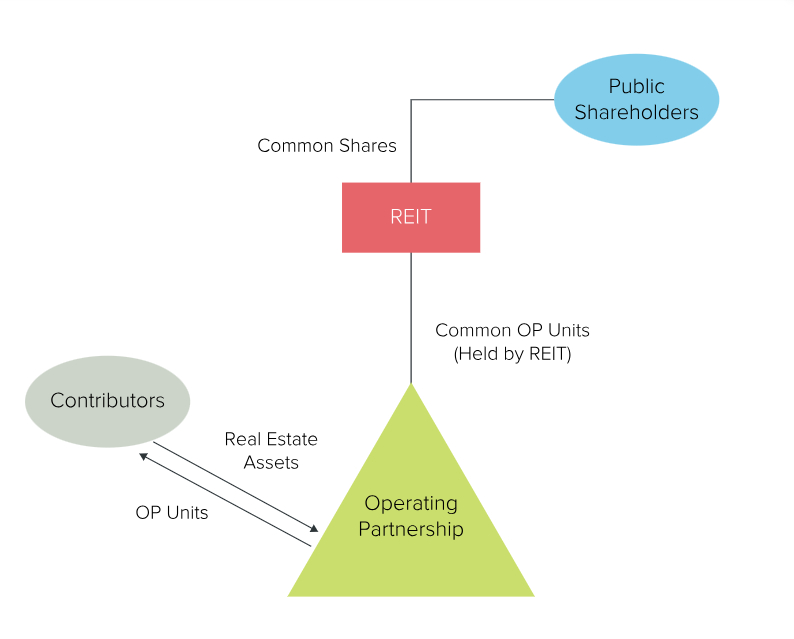

In the UPREIT structure, the REIT holds essentially all of its assets through a subsidiary operating partnership of which the REIT is the sole general partner.1 Because the REIT's assets consist primarily of its interests in the operating partnership, an investment in the operating partnership is the economic equivalent of an investment in the REIT.2 Specifically, in the UPREIT structure each outstanding share of REIT capital stock is "mirrored" by the REIT's ownership of a corresponding unit of interest in the operating partnership. These partnership units are entitled to receive ordinary and special distributions that are identical in amount to any dividends declared on the corresponding shares of the REIT.3

In the classic OP unit transaction, third-party owners of appreciated real estate contribute their property(ies) directly to the operating partnership on a tax-deferred basis (i.e., without recognition of gain or loss) in exchange for common limited partnership interests, or "OP units." In contrast, a sale of the same property for cash (outside of Section 10314), or a direct contribution to the REIT in exchange for REIT stock, would be fully taxable.

The basics of an OP unit contribution transaction with an UPREIT can be diagramed as follows:

As noted above, the economic value of a common OP unit is intended to be functionally equivalent to that of a REIT common share. The number of OP units issued to contributors upon the contribution of their assets to the operating partnership is thus usually determined by dividing the negotiated net equity value of the contributed property by the market value of REIT common shares. The market value of REIT common shares used in the transaction can be fixed at signing, float through closing, be determined by spot market prices or based on volume-weighted average prices over a specific number of trading days before signing or closing. The value can also be subject to a cap and/or a floor. These mechanics are the subject of pre-signing negotiations among the parties and often tailored to reflect individual circumstances and preferences.

Once the contribution transaction has been completed, the partnership agreement typically provides contributors with a contractual option, exercisable after a negotiated lock-up period, to have their common OP units redeemed for a cash amount per unit equal to the then-current market value of a REIT common share or, at the REIT's discretion, exchanged for actual REIT common shares on a 1-for-1 basis. The lock-up period is commonly 12 months but can also be shorter depending on circumstances. This liquidity mechanism built into the UPREIT structure enables contributors to monetize their investment at the time of their choosing. Since, as discussed below, any such exchange or redemption of OP units is immediately taxable to the contributor whether or not the REIT shares received in exchange are sold, most contributors will only exercise the redemption/exchange option to extent they intend to promptly resell any such shares for cash. Refer to "Securities Law Considerations" below for a discussion of a contributor's ability to freely resell REIT shares received in exchange for OP units under the federal securities laws.

Though less common, the flexibility of the UPREIT structure also permits OP unit exchanges to be structured other than as issuances of common OP units. Depending on the circumstances, contributors may want different economics or a structure that delivers different rights as compared to common OP units, such as convertible/redeemable preferred units. Specific economic features that have been used in the past include a required minimum dividend or a conversion premium to address the business objectives of the parties.

II. Key Tax Benefits and Considerations for Contributors

The primary benefit to contributors in OP unit transactions is that the contribution is designed to avoid current taxation.5 It is only upon redemption of the OP units for cash or REIT shares that contributors are taxed on the gain in the redeemed OP units, including any previously deferred gain. The OP unit transaction structure also generally allows the contributor to enjoy capital gain treatment when the deferred gain is ultimately triggered, in contrast to alternative structures such as prepaid ground leases that generate ordinary income.

Moreover, in the case of OP units included in a contributor's estate, if the contributor dies before exercising the redemption option, their estates and heirs will receive a "step-up" in tax basis for the OP units to the then fair market value (ordinarily the trading price of an equal number of REIT shares), thus eliminating the built-in gain on the OP units entirely for federal income tax purposes.6

OP units received by non-corporate contributors with multiple members often can be distributed by the contributor entity to its members on a tax-deferred basis as well, thereby allowing each member to independently decide when to exit by redeeming all or a portion of its OP units, without affecting other members.

Contributors must weigh these benefits against certain risks and increased burdens. As limited partners of the operating partnership, OP unitholders are taxed on their share of the operating partnership's taxable income. If distributions do not match taxable income allocations, they may face "phantom income" (i.e., taxable income as partners requiring tax payments in excess of distributions received).7In addition, as partners in the operating partnership, OP unitholders generally will be required to file state (and possibly local) tax returns in jurisdictions in which the operating partnership does business or owns property.

Although the partnership tax rules are designed to facilitate tax-deferred contributions to operating partnerships, the parties and their advisors will need to navigate complex partnership tax rules and regulations to achieve the desired outcomes with acceptable levels of risk. For example, the parties must navigate certain "disguised sale" rules if the contribution includes cash payments or assumptions of certain "nonqualified" liabilities. Consideration also must be given to "negative capital accounts", which occur when the contributor holds its property subject to liabilities that exceed contributor's tax basis in the property (or a member of a contributing partnership has a share of contributing partnership liabilities that exceed the member's tax basis in its interest in the contributing partnership). Negative capital accounts are common in real estate and often arise from cumulative depreciation deductions that exceed the contributor's equity in the property and distributions of excess refinancing proceeds. In these cases, taxable gain can arise upon contribution of the property to the operating partnership if and to the extent that the contributor's share (or the share of a member of the contributor) of operating partnership liabilities is less than its pre-contribution negative capital account. As a result, when structuring an OP unit contribution transaction, the contributor (and its members in the case of a partnership contributor) generally must be allocated a share of operating partnership liabilities sufficient to "cover" their respective negative capital accounts. Additional considerations arise for contributors whose negative capital account also is subject to "at-risk" recapture.

Well-advised contributors of property often seek to require the REIT to provide a "tax protection" mechanism to ensure that the tax deferral achieved by the contribution continues for a negotiated period of time. Frequently arising challenges to achieving and preserving tax deferral, including liability allocations and negative capital account coverage, are discussed in further detail in Section V below.

III. Cash Payments in OP Unit Transactions

Parties to OP unit transactions frequently seek to provide that the contributor will receive, or have the option to receive, cash consideration for some portion of the value of the contributed property. Under applicable tax rules, however, cash payments to a contributor by the operating partnership within two years of a contribution (other than normal operating cash flow distributions) may trigger recognition of a portion of the contributor's gain under the "disguised sale" rules. Moreover, the operating partnership's assumption of liabilities with respect to the contributed property, and/or the repayment of any such assumed liabilities, may effectively be treated as a cash payment to the contributor for purposes of the disguised sale rules.

Nevertheless, it is often possible for contributors to receive limited amounts of cash in connection with OP unit transactions, or for the OP to assume liabilities, without triggering a disguised sale. There are three main categories of permissible cash payments that, if properly structured, may avoid triggering a disguised sale:

Pre-Formation Expenses

Reimbursements to contributors for capital expenditures with respect to the contributed property will not trigger a disguised sale, provided that the reimbursed expenditures:

- are incurred within two years preceding the closing of the contribution; and

- do not exceed 20% of the fair market value of the property at the time of contribution (if the property value at such time exceeds 120% of the contributor's tax basis in the property; otherwise, no such limitation applies).

A contributor will be required to recognize gain to the extent that the amount distributed for pre-formation expenditures exceeds the contributor's tax basis in its OP units (including tax basis resulting from allocations of operating partnership debt to the contributor).

Leveraged Distributions

A distribution of 100% of the proceeds from new debt incurred by the operating partnership, if made within 90 days of the incurrence of the debt, is generally permitted if the debt is "allocated" to the contributor. To receive this debt allocation, the contributor must guarantee the debt, and the guarantee must have sufficient economic substance to be respected for tax purposes.

Qualified Liabilities

Assumption by the operating partnership of "qualified liabilities" does not trigger disguised sale treatment.8 Qualified liabilities include:

- debt encumbering the contributed property incurred more than two years before the contribution closing;

- debt encumbering the contributed property incurred within two years if it is clearly not in anticipation of the contribution;

- debt used for capital expenditures or acquisition of the contributed property; and

- debt incurred in the ordinary course of business related to the property.

On the other hand, assumptions of liabilities that are not qualified liabilities generally will trigger some amount of disguised sale treatment absent guarantees of the entire amount of the assumed debt by the contributor.9

When the contributor is itself a partnership, the contributor's partners may have the option of receiving cash for their interests in the contributor in a taxable exchange rather than taking OP units. If properly structured, the election by some members to take cash should not trigger tax gain for the other members by taking advantage of special partnership merger rules.

IV. Corporate Governance and Mechanics

While common OP units and REIT common shares are economically equivalent, as illustrated in the diagram above, the legal rights they confer differ significantly.

A REIT is a corporation or trust, managed by a board of directors or trustees, with shareholders having the right to elect directors/trustees and vote on all other matters presented at shareholder meetings. In contrast, the operating partnership is a limited partnership managed by its general partner (typically the REIT or a subsidiary of the REIT). As limited partners, the rights of OP unitholders are governed by the terms of the operating partnership agreement; OP unitholders do not have any of the rights of shareholders of the REIT.

Fiduciary Duties and Conflicts of Interest

The economic interests of REIT shareholders and OP unitholders are usually aligned, as both are investors in the common equity of the same enterprise. However, conflicts can arise — for example, when a sale or refinancing is beneficial to the REIT but imposes adverse tax consequences on individual OP unitholders.

Under Delaware law, which governs most operating partnerships, partnership agreements can expand or limit fiduciary duties. Most modern UPREIT operating partnership agreements state that, in case of conflict, the REIT/general partner fulfills its duty to OP unitholders by acting in the best interest of REIT shareholders. The REIT board may rely on this contractual provision to meet its fiduciary obligations, though many operating partnership agreements provide that the general partner must also consider in good faith any mitigating actions to lessen negative effects on OP unitholders.

Voting Rights of OP Unitholders

At the parent REIT level, OP unitholders have no vote at all. At the OP level, they generally have no voting rights either, except for amendments to the operating partnership agreement that would materially and adversely affect them — such as changes to provisions on distributions, allocations, or redemptions. Public markets heavily disfavor granting OP unitholders blocking or consent rights to transactions otherwise approved by REIT shareholders. In the case of extraordinary transactions, operating partnership agreements typically provide that OP unitholders do not have a separate consent right, so long as they have the right to receive an amount of cash and/or securities per unit equal to what is to be received per each REIT share in the transaction.

Of course, OP unitholders generally have the ability to tender their units for redemption and exchange for REIT shares prior to important shareholder votes, though this exchange would be a taxable event. Refer also to the discussion under the "Redemption Right Mechanics" subsection below for considerations relating to possible limitations on free exchange due to the REIT's charter ownership limitation provision.

At the IPO formation stage of some UPREITs, particularly where pre-IPO investors will have a significant economic stake in the post-offering enterprise in the form of OP units, a "dual-class" voting structure is established that permits OP unitholders to vote their economic interest at the REIT level. This structure is typically effected by offering legacy investors, at the time of the REIT formation transactions and IPO, a separate class of high-vote REIT common stock with voting power that approximates the total number of common OP units they hold. (For example, one share of 50-vote Class B common stock in place of every 50th OP unit to which they would otherwise be entitled.) Many institutional investors and corporate governance watchdogs generally disfavor dual-class voting structures on the assumption that they might contribute to entrenching management control.

Redemption Right Mechanics

As previously noted, the redemption feature is a key liquidity feature of the OP unit structure. Once the lock-up period applicable to the OP units issued to contributors ends, OP unitholders can exercise a right to have all or some of their units redeemed by the operating partnership. The redemption right allows unitholders to tender their units to the partnership for cash, in an amount per unit equal to the then-current market value of a REIT share (as determined pursuant to the applicable provisions of the operating partnership agreement). The general partner, in its sole discretion, may elect to satisfy the redemption request with actual REIT shares in lieu of cash.

In practice, absent any structural or legal restrictions, REITs almost always choose to settle redemptions through the issuance of REIT shares, preserving the nature of the original property-for-equity transaction. The exchange does not reduce the number of outstanding OP units — it merely transfers ownership of those units from the unitholder to the REIT. It does, however, increase the public float of the REIT. Thus, the decision to redeem in cash or stock typically revolves around the availability of sufficient cash and the desirability of reducing the public float, as in a stock buyback.

Redemption is a taxable event, whether for cash or for REIT shares, triggering gain to the extent of appreciation in the redeemed units and any built-in gain inherent in the contributed assets at the time of contribution. This built-in gain may be significant and serve as a deterrent to redemption by the unitholder.

To effect a redemption, unitholders typically must submit a redemption notice, a FIRPTA certificate, and an instruction letter to the REIT's transfer agent. In the redemption request documentation, the tendering OP unitholder must confirm the satisfaction of various conditions to receiving REIT shares set forth in the operating partnership agreement, including its ownership of the tendered OP units free and clear, and its status as an "accredited investor" for federal securities law purposes. In most cases, the stated conditions are easily satisfied, but there are instances — for example, where one or more OP unitholders holds a sizable percentage of total equity interests — when a given OP unitholder will not be able to exchange all or some of its units for REIT shares without violating the ownership limits set forth in the REIT's charter.10

Once an exchange of OP units for REIT shares is approved and the process initiated, it is generally critical to OP unitholders to avoid market risk between the time taxable gain is recognized (i.e., the time the units are exchanged for shares) and the time the REIT shares are monetized and sold into the market. The provisions of the operating partnership agreement or the contribution agreement are often structured to allow "seamless liquidity" so that an OP unitholder can be assured that any REIT shares issued upon redemption of OP units can be immediately sold into the trading market to fund taxes and avoid market risk.

Mergers and Go-Private Transactions

Certain capital transactions may impact OP unitholders differently than they do REIT shareholders:

- A transaction at the REIT (parent) level, where OP unitholders remain in the operating partnership, typically does not affect tax deferral. This generally includes most public-to-public merger transactions where OP unitholders of the target REIT are offered the ability to retain OP units in the surviving operating partnership in lieu of receiving cash or stock merger consideration.

- A transaction at the operating partnership or asset level, where OP unitholders receive non-tax deferred consideration, will usually trigger recognition of built-in gain. This generally includes parent-level merger and acquisition transactions in which OP unitholders of the target REIT are cashed out and/or receive stock alongside REIT common shareholders.

- Changes in debt treatment or allocation may also negatively affect OP unitholder tax outcomes.

As previously noted, most operating partnership agreements specify that OP unitholders do not have a separate vote or blocking right on extraordinary transactions, so long as they have the right to receive the same consideration as REIT shareholders — meaning that different tax implications for OP unitholders do not alone generally trigger any consent requirements. As discussed in further detail in the following section, however, contributors prioritizing protection from the adverse tax effects of extraordinary transactions will often seek such protection in tax protection agreements at time of contribution.

A public REIT's board must very carefully weigh the costs and benefits to shareholders of entering into tax protection or other agreements that would make the acquisition of the REIT prohibitively expensive for would-be acquirors (or limit the universe of potential acquirors to other public UPREITs). Over the years, practitioners including Goodwin's REIT M&A and Tax attorneys have developed structures that would permit taxable transactions to proceed at the REIT level (e.g., "go private" transactions) while maintaining the tax deferral of all or some OP unitholders. This generally involves offering OP unitholders a tax-deferred alternative to cash or stock merger consideration, such as OP units in a continuing private partnership. 11 The redemption right can also be preserved in this iteration, even if the ability of the general partner to satisfy redemption requests with publicly traded common stock would generally be lost. Please refer to our alert: Privatizing Public REITs: Strategic Considerations and Legal Insights for a broader discussion of go-private transaction considerations in the sector.

V. Tax Protection Agreements

A tax protection agreement (TPA) is a contractual arrangement designed to preserve a contributor's tax deferral for a specified term. These agreements are often heavily negotiated and tailored to specific deals; there is generally no standard form.12 TPAs can be contained in the operating partnership agreement or in a separate agreement.

TPAs are designed to protect contributors from actions by the operating partnership that accelerate recognition of the contributors' deferred gain. The TPA typically does not protect contributors if the intended tax treatment of the initial contribution is challenged or otherwise allocate "tax risk" with respect to the initial structure of the transaction (i.e., the operating partnership does not have to indemnify the contributor if the IRS successfully challenges the contribution as not qualifying for tax-deferred treatment).

The term of the TPA (or of the different elements of the TPA) is subject to negotiation. Five to seven years is not uncommon, but terms vary widely. TPAs often terminate early if a specific percentage of the initial OP units is transferred, exchanged or otherwise disposed of by the contributors or upon similar events. In the early years of the UPREIT structure, longer tax protection periods were more common, but these have become less prevalent in current markets.

As discussed in detail below, key areas typically addressed in tax protection agreements include:

- Taxable Sale Provisions: Restrictions on sales or other taxable dispositions of the contributed property for a specified period;

- Tax Allocation Methods: Adoption of a Section 704(c) depreciation allocation method to minimize adverse tax consequences to contributing partner;

- Negative Capital Account Protections: Minimum allocation of partnership debt (and at-risk coverage); and

- Remedies for Breach: Monetary damages if the operating partnership breaches its obligations under the tax protection agreement (but not a veto right).

Taxable Sale Provisions

Under the partnership tax rules, a taxable sale or other taxable disposition of the contributed property generally triggers the contributor's deferred gain. Accordingly, a standard TPA requires the operating partnership to indemnify the contributors for tax costs resulting from any such disposition during the term of the TPA. Because a taxable exchange of OP units for REIT shares, cash or other taxable consideration—such as in a taxable merger, go-private transaction or other "fundamental transaction"—also will trigger contributors' deferred gain, a standard TPA also requires indemnification if the contributor is forced to exchange its OP units on a taxable basis in connection with certain fundamental transactions.

Common exceptions to tax protection provisions (i.e., permitted dispositions that do not trigger tax protection damages) include:

- tax-free exchanges (although replacement property remains subject to tax protection);

- eminent domain (provided the operating partnership uses commercially reasonable efforts to defer the contributor's gain under Sections 1031 or 1033);

- tax-free contributions to joint ventures, provided no gain is recognized; and/or

- fundamental transactions where contributor is offered a tax-deferred alternative to the taxable consideration (regardless of whether the contributor elects the tax-deferred option).

Some TPAs require the REIT to make good faith efforts to structure a sale of the contributed property as a 1031 exchange, to distribute the contributed property back to the contributor after the tax protection period expires or to continue to provide debt protection until the contributed property is sold. However, REITs typically prefer clear cutoff dates for their obligations.

Section 704(c) Allocations

Most TPAs mandate the "traditional method" under Section 704(c) for tax depreciation allocations with respect to the contributed property. However, this method may reduce tax depreciation available to the REIT and other non-contributing partners as compared to tax depreciation that the REIT and others would enjoy if the REIT purchased the property for cash and obtained a basis step up.

Alternative methods that better preserve REIT depreciation may accelerate recapture of built-in gain for contributors.

Negative Capital Account Protections

As noted above, to avoid immediate gain recognition in the contribution, a contributor (and/or a member of a partnership contributor) must be allocated a share of operating partnership liabilities at least equal to its negative capital account. This allocation may be achieved via debt guarantees and/or certain nonrecourse debt.

Guarantees. A properly structured guarantee attracts an allocation in the amount of the guaranteed debt. Guarantees must have economic substance under the tax regulations, among other requirements necessitating that a sufficient amount of assets be held by an entity guarantor to support the guarantee. So-called "bottom-dollar" guarantees will not attract a debt allocation and the guarantor also cannot have rights of contribution or indemnity against other partners. In light of the economic risk required for guarantees to attract debt allocations under the regulations, contributors often negotiate the quality and terms of the debt they guarantee (or that must be offered for guarantee if the original guaranteed debt is no longer available (e.g. upon the maturity of the original debt or upon refinancing)).

Non-recourse debt. In many cases the REIT agrees to avoid recapture of negative capital accounts by maintaining sufficient non-recourse debt that encumbers the contributed property. Use of non-recourse debt is relatively straightforward (and the operating partnership typically can satisfy its debt-maintenance obligations) if it is secured solely by the contributed property and refinanced solely with non-recourse debt secured solely by the contributed property in an amount not less than the balance of original debt at contribution. In other cases, providing the contributor with an adequate allocation of non-recourse debt can be more complicated.

TPAs vary widely in balancing the interests of the REIT and operating partnership, on one hand, versus those of contributors, on the other hand. The REIT/operating partnership desires both flexibility to provide adequate debt allocation through any means, as well as "safe harbors" (such as maintaining a minimum non-recourse debt amount on the contributed property or the ability to substitute guarantees). Conversely, contributors typically seek to allocate as much risk of a debt allocation shortfall to the operating partnership as possible and to avoid being forced into guarantees.. In all cases, the operating partnership needs to consider how its debt allocation obligations under the TPA could constrain its financing strategies going forward.

Remedies for Breach

Typically, remedies for breach of the TPA by the operating partnership are limited to a measure of damages based on the amount of tax incurred by the contributing partner as a result of the breach. Remedies generally do not include specific performance.

The most common damage provisions in a TPA provide for full indemnification by the operating partnership for all taxes triggered plus a "gross-up" for taxes on the indemnification payment. The taxes owed may be determined by formula and are typically calculated with reference to the built-in gain at time of contribution (i.e., excluding taxes attributable to post-contribution appreciation).

Less common in current TPA formulations, but preferable for the operating partnership, are damage calculations that compensate the protected partner solely for the time value of money on the acceleration of taxes arising from the breach as compared to if such taxes had been triggered when the protection period expired.

As noted earlier, significant indemnification obligations under TPAs at the operating partnership level can make a taxable acquisition of the REIT prohibitively expensive for would-be acquirors. Where material, this could be reflected in the REIT's market trading price. It is critical to consult with counsel when drafting TPA indemnification provisions to ensure that the provision of an appropriate tax-deferred option in a taxable acquisition of the REIT does not set off an indemnification obligation under the TPA.

VI. Securities Law Considerations

OP units are "securities" for purposes of the federal and state securities laws. As such, both REITs and contributors must be mindful of applicable securities laws at each stage of the transaction, including initial issuance of OP units, the later exchange of OP units for REIT shares, and the sales of such REIT shares into the market.

Initial Issuance of OP Units

The contribution of property to the operating partnership in exchange for OP units constitutes an offer and sale of securities by both the operating partnership, as the issuer of OP units, and the REIT, as the entity with the right to issue REIT shares upon redemption of OP units. In the majority of cases, the offer and sale of OP units is structured to qualify for an exemption from the registration requirements of the Securities Act, as well as the securities or "blue sky" laws of the states where the contributors reside.13 While some form of private placement exemption is most commonly used, several different exemptions may be available, each with its own pros and cons and applicable requirements. Each transaction requires a careful analysis of the facts and circumstances to ensure the conditions for the exemption, which the parties intend to rely on, are satisfied.

For example, in transactions where the operating partnership will issue units to a private limited partnership that owns the to-be contributed property, the exemption analysis may need to be conducted on a "look through" basis to each limited partner of the contributing entity, particularly if a vote of limited partners is necessary to approve the transaction. In certain scenarios, such as where there are non-accredited investors among the limited partners, a transaction can be structured to provide for the contributing entity to hold the OP units and not distribute them out to limited partners for a significant period (the so-called "coming to rest" concept).14

Getting the securities analysis and exemptions right is of critical importance to the integrity of the transaction. If the offer and sale of OP units fails to satisfy each and every condition for exemption from registration, the contributors may be entitled to significant remedies, including the right to demand rescission of the transaction entirely. In extreme cases, failure to comply with all the requirements of a particular exemption results in giving contributors a "free option" on the transaction as a whole, meaning they could seek rescission after the fact if, say, the price of a REIT share declines materially from its value at time of contribution.

Exchange and Sale of REIT Shares

As previously noted, access to prompt liquidity in connection with the realization of taxable gain upon redemption of OP units for REIT shares is critical for contributors. In most cases, under current guidance, so long as contributors have held their OP units for at least six months, the REIT shares received upon exchange are immediately freely tradeable in the public markets. This treatment is based on an SEC no-action letter issued in 2016 that, in recognition of the economic equivalency between OP units and REIT shares, permits OP unitholders to "tack" the holding period of their units to the REIT shares received upon redemption.15 As a result, the REIT shares received in exchange for OP units can be sold without an additional holding period, notwithstanding that such REIT shares are technically "restricted securities," meaning securities issued in transactions exempt from the registration requirements of the Securities Act and, therefore, subject to certain limitations on transfer to comply with the federal securities laws.16

Historically, the six-month holding period for "restricted securities" began anew upon exchange of OP units for REIT shares, because they are the securities of two different issuers. This fact meant that, prior to the SEC's no-action letter permitting tacking, prompt resale into the market of the REIT shares was generally not permitted absent the registration of the REIT shares under the Securities Act, leading contributors to negotiate separate registration rights agreements. Since 2016, registration rights agreements are either not entered into at all in connection with OP unit transactions or typically only provide passive registration rights that require the REIT to register the resale of the REIT shares issued upon an exchange of OP units if the Rule 144 exemption is not available.

VII. Other Uses of the UPREIT Structure

While the UPREIT structure was initially developed to facilitate the common OP unit contribution transactions described in detail above—the structure has proven to be a flexible one. As noted above, the structure can also accommodate the use of more complex securities as consideration for acquisitions, such as preferred or convertible units.

While beyond the scope of this article, a well-known additional development of the UPREIT structure is the use of tax-advantaged profits interests, or LTIPs, as substitutes for REIT stock in equity compensation plans. Goodwin's REIT M&A and Tax attorneys were instrumental in pioneering this important feature of executive compensation programs in the modern REIT sector.

In addition, the UPREIT structure can facilitate direct investment(s) at the operating partnership level, for example in cases where the ownership limitation provisions in the REIT's charter might preclude a large investment in the REIT. Similarly, an operating partnership contribution may be a viable exit for property owners of replacement property previously acquired in a Section 1031 exchange.

In our view, the UPREIT structure will continue to evolve to meet today's challenges.

Footnotes

1 The general partner can also be a wholly-owned subsidiary of the REIT. The "operating partnership" can also take the form of a limited liability company taxed as a partnership, in which the REIT (or its wholly-owned subsidiary) is the sole managing member. For purposes of this article, we refer to all operating partnerships as "partnerships" consistent with their intended tax treatment.

2 If a REIT holds substantial assets outside the operating partnership, the operating partnership is commonly referred to as a "downREIT." DownREITs are typically designed so that a downREIT partnership unit can be viewed economically equivalent to a share of REIT common stock, and many of the issues addressed in this article also apply to downREITs. However, a discussion of downREITs is beyond the scope of this discussion. Likewise, a detailed discussion of private UPREITs or downREITs is beyond the scope of this discussion.

3 Payment of dividends at the REIT level is thus funded by the distributions paid by the operating partnership with respect to the corresponding partnership interests held by the REIT.

4 Section references are to the Internal Revenue Code, unless otherwise noted.

5 Because the contributor does not recognize gain upon the contribution of property to the operating partnership, the operating partnership does not get a basis step-up, and the REIT therefore has lower depreciation deductions compared to if it purchased the property in a taxable transaction. Fewer deductions mean more taxable income and a larger distribution requirement for the REIT. Thus, the tax-deferred nature of the OP unit transaction, while beneficial to the contributors, has a cost to the REIT.

6 This benefit is generally not available for OP units held in trusts that are not included in the contributor's estate. .

7 Contributors intending to rely on losses from other sources to shelter income generated by their OP units should consult their tax advisors regarding various generally applicable limitations of their ability apply any such losses against their shares of operating partnership income.

8 The disguised sale exception for assumptions of qualified liabilities does not apply if the operating partnership does not assume the liability but instead makes a cash payment to the contributor to repay the qualified liability.

9 A deemed payment arising from an assumption of a non-qualified liability might be sheltered as a reimbursement of pre-formation expenditures to the extent available.

10 Ownership limitation provisions are intended to ensure compliance with the so-called "5/50" test, pursuant to which five or fewer individuals may not own more than 50% of the value of a REIT's capital stock, and avoid any related party tenant issues. Refer to our alert "Waivers of Ownership Limitation Provisions in REIT Charters" for a more detailed discussion of REIT charter ownership limitation provisions.

11 A structure of this sort was challenged by unitholders with tax protection agreements in the 2007 Archstone go-private transaction. Archstone prevailed in litigation with the assistance of Goodwin, who served as expert witness for Archstone. Note that any future litigation on issues like this will likely be heavily dependent on the specific language of the relevant contracts.

12 Some REITs have developed forms of contribution agreements, including TPAs (that they intend to offer on a "take it or leave it basis") for example, in hopes of limiting transaction costs in smaller OP units transactions.

13 The applicability of state securities and "blue sky" laws can be tricky, as many states take a very expansive view of what constitutes "residence" for the protection of investors and the interplay of federal and state law can be intricate. In addition, the issuance of a large number of OP units may trigger SEC disclosure obligations under Form 8-K (Item 3.02, Unregistered Sales of Equity Securities).

14 In REIT formation transactions, care must also be given to the special rules applicable to "roll-up transactions" under Item 900 of Regulation S-K. Wherever possible, contributions of property for OP units must be carefully structured to avoid implicating the roll-up transaction rules, since these would impose additional and burdensome requirements.

15 Bank of America, N.A., Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated (March 14, 2016). In the no-action letter, the SEC noted that it relied in particular on the following points in reaching its conclusion: (1) that the unitholders paid the full purchase price for the OP units at the time they were acquired from the operating partnership, (2) an OP unit is the economic equivalent of a REIT share, representing the same right to the same proportional interest in the same underlying pool of assets, (3) the exchange of REIT shares for OP units is entirely at the discretion of the REIT, and (4) no additional consideration is paid by the unitholders for the REIT shares. See, also, "SEC Permits Immediate Resale Under Rule 144 of REIT Shares Issued in Exchange for OP Units," Goodwin's discussion of the no-action letter.

16 See Rule 144 under the Securities Act. The principal restriction on the sale of restricted securities is a six-month holding period prior to resale. The six-month holding period applies to issuers that are current in their SEC filings and have been SEC reporting companies for 90 days. For issuers that have not been SEC reporting companies for 90 days, the holding period is one year. The same holding periods apply to affiliates of issuers, but affiliates are subject to volume limitation and other requirements under Rule 144.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.