- within Technology topic(s)

- within Technology, Intellectual Property and Tax topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

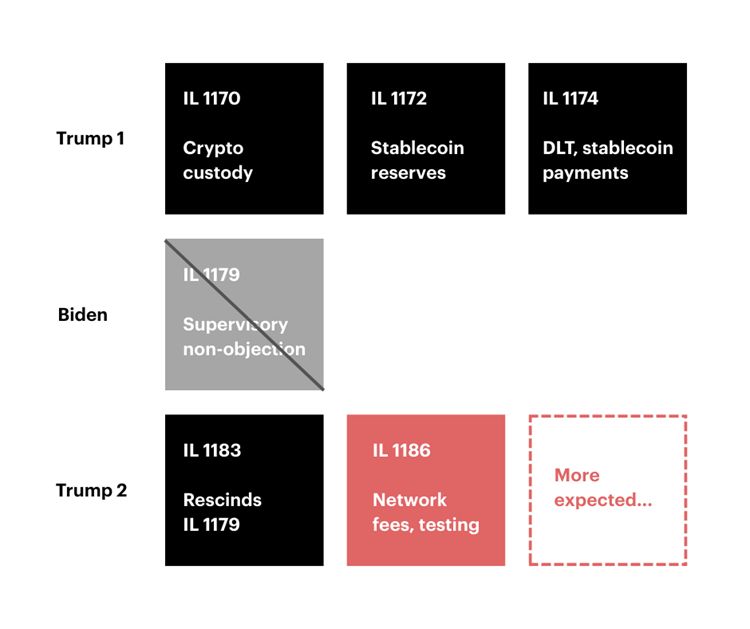

The OCC issued Interpretive Letter 1186, confirming that national banks may hold crypto-assets as principal to pay network "gas fees" and to test crypto platforms. IL 1186 builds upon the foundation laid during the first Trump Administration and reflects the second Trump Administration's regulatory priorities and supervisory posture. More clarifications from the OCC on digital assets are expected to follow. If the OCC continues at this pace, DeFi is poised to become the "electronic" and "internet" activities of the 1990s—just another thing banks can do. This is just the latest step in promoting the interoperability of crypto and blockchain technologies with traditional financial services.

The OCC also released a public database of prior requests for supervisory non-objections for permissible crypto-related activities under a now-defunct framework. The database provides overdue transparency into an opaque process marked by delays and uncertainty.

Key Takeaways

- National banks and operating subsidiaries may hold and pay network fees in crypto-assets as principal as activities "incidental to the business of banking."

- National banks may hold crypto-assets to test otherwise permissible platforms, whether internally developed or from a third party, as incidental to the business of banking.

- IL 1186 is the logical continuation of the Brooks-era interpretive letters that found node activities and other crypto-related activities permissible (e.g., crypto custody, stablecoin activities).

- The IL hints that more interpretations are likely by noting that national banks "may also hold some amount of crypto-assets as principal for other permissible purposes." Banks interested should continue to work with the OCC to clarify and widen the scope of activities that qualify under this expanded interpretation of permissible activities.

- The IL unsurprisingly clarifies that operating subsidiaries may engage in these incidental activities, too. That gives national banks structural flexibility and should help with GENIUS Act compliance.

- These clarifications and insights from the OCC seem to open the door for the ability of national banks to facilitate securing yield or rewards for stablecoin ownership. Whether a market structure bill addresses this issue remains an open question.

- Federal branches of foreign banks and national trust banks may also leverage IL 1186 and its predecessors.

- State-chartered banks whose home state laws incorporate national bank powers may also benefit from this determination.

In Context

IL 1186 reflects the OCC's broader effort under Comptroller Jonathan Gould—the agency's former Chief Counsel who developed key Brooks-era interpretations on crypto-related activities—to modernize the OCC's approach. Comptroller Gould has emphasized his intent to put OCC supervision and expectations "on a firmer legal foundation" and IL 1186 follows a string of proposed reforms to supervision.

IL 1186 also continues the trend of the first Trump Administration's ILs that clarified that national banks may engage in key crypto-related activities.

IL 1186 is very much the logical outgrowth of these ILs, especially IL 1174:

- Specifically, IL 1186 was issued in response to a bank's request to conduct crypto-asset activities that the OCC previously determined permissible under 12 U.S.C. § 24(Seventh) or that is expressly allowed under the soon-to-be-effective GENIUS Act.

- Because these activities would likely incur network fees, banks

want to hold crypto-assets as principal or agent under a custody

agreement.

- DLT networks require users to pay fees in the network's native crypto-asset to validate or record transactions, regardless of which token or smart contract the customer actually uses to complete the transaction. These fees help protect a DLT network against attempts to maliciously flood the network with excess data in a denial-of-service type of attack. Each attempt to engage with the DLT network incurs a fee, and using third parties to pay such fees causes delays and exposes the bank to risk.

- The bank explained how it would conduct the activities in a safe and sound manner and maintain appropriate risk-management processes and controls.

- The OCC recognized that banks may need to step in to keep permissible crypto-asset activity moving and provided an express clarification to do so. Notably absent were granular regulator-specified quantitative and qualitative tests that were not developed in regulation or required by statute. Instead—and consistent with the OCC's recent supervisory approach—a national bank may now enjoy some flexibility to conduct the limited activity to the extent needed to pay reasonably foreseeable fees or test otherwise permissible platforms.

We note that the bank's explanation of how it would ensure that its activities would be conducted in a safe and sound manner is something of a roadmap for banks and others seeking future OCC clarification.

Why It's Permissible

Under the permissibility analysis framework in 12 C.F.R. § 7.1000(d), an activity is permissible if it:

- Facilitates delivery and improves efficiency with risk controls. Allowing a bank to pay network fees or hold a small amount of native tokens required to pay them, directly facilitates the delivery and improves the efficiency of otherwise permissible activities in the bank's course of business.

- Enables the bank to use existing capacity to avoid economic loss or waste. Many banks already have the operational capacity to buy, sell, and hold crypto-assets for custody, stablecoin, or other permissible activities. By permitting banks to hold and pay the small amount of native tokens needed for network fees, institutions may avoid contracting with third-party fee providers*, avoiding unnecessary costs and leveraging existing capacity.

*We note that banks that don't have the operational or compliance capacity in place to leverage this authority very well may want to use third-party fee providers—at least until they are ready to conduct the activities in a safe and sound manner and with appropriate risk controls.

IL 1186 also analogizes holding crypto-assets as principal to long-standing practices in traditional payment systems, where banks have typically invested capital in "building, joining, or maintaining the network[.]" In that way, using these technologies is just a new way to "conduct[] the very old business of banking."

Testing

IL 1186 applies the same permissibility analysis to crypto-asset platform testing. A bank developing or acquiring a crypto-asset platform must be able to test transfers, settlement, recordkeeping, controls, and compliance before putting the service in front of customers. Banks, therefore, may hold the amount of crypto-assets needed to test platforms, helping banks avoid increased costs and heightened operational risks, while encouraging banks to test systems thoroughly.

More to Come

IL 1186 doesn't suggest this is the end of clarifying permissible crypto-related activities for national banks.

By revisiting and developing previous ILs, conducting an incidental activities analysis, and analogizing these new activities to long-standing payment systems practices, the OCC has charted a viable way forward.

In addition, the OCC notes in footnote 35 that national banks "may also hold some amount of crypto-assets as principal for other permissible purposes" that are unspecified and thus quite broad. The OCC gives two examples: (1) foreclosing on crypto-assets used as collateral for a loan; or (2) physically hedging a customer-driven derivative on a crypto-asset in conformity with 12 C.F.R. § 7.1030. Taking the OCC's statement at face value and to its logical conclusion, there are likely many more "permissible purposes," including possibly:

- Various short-term facilitation activities

- Holding de minimis assets acquired as a byproduct of operations

- In various FX and other execution contexts

- BaaS operational contingency reserves (to the extent not covered under custody powers)

- Audit/fraud-mitigation or forensics activities

- Escheatment contexts

Public Database of Former Supervisory Non-Objection Requests

The OCC also released a Summary of Interpretive Letter 1179 Requests database to show how its earlier interpretations were applied in practice under the now-defunct supervisory non-objection framework of the prior administration. It provides overdue transparency and follows the FDIC's release of the crypto letters earlier in 2025 in response to reports and allegations of debanking.

While the disclosure of 21 "formal requests" over two years is useful, the submissions represent fairly measured requests to update banking systems and processes. Banks that sought to modernize banking businesses faced an opaque agency process that added costs and delays. Some received a supervisory non-objection, while many didn't; those who didn't, withdrew their requests—a practice that previously typified the application process at other federal banking agencies.

The controls the OCC specified for those that received a non-objection are not terribly informative, either. Providing the OCC's interpretations more broadly through general guidance or developed regulation could have promoted consistent and specific risk controls, through a transparent routine process, backstopped by supervisory oversight.

The database moreover doesn't show the many informal requests the OCC presumably received during this period, which we imagine would significantly expand the dataset.

Our Take

IL 1186 is helpful as national banks and others develop their products and services. It also confirms the new supervisory approach that the OCC announced.

We expect additional guidance from the OCC to promote innovation in financial services, banking, and payments. Banks and traditional financial institutions remain at the heart of the U.S. financial system and integrating the best technology from blockchain and crypto use cases constitutes the next step in creating the future generation of financial products and services.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.