- within Transport topic(s)

Key Takeaways

- EPA is evaluating the Texas Railroad Commission's formal primacy application. If granted, Texas will assume primary enforcement authority—or primacy—over Class VI wells.

- Carbon capture and storage proponents have pushed for state primacy over Class VI wells as a solution to federal permitting delays.

- Ongoing legal disputes over primacy grants and other CCS issues—including Class VI permit appeals, environmental impact reviews, and pipeline controversies—may mean further challenges for CCS projects.

State primacy over injection wells used in carbon capture and storage (CCS) remains in the news after Texas took a key step towards becoming the fifth state to assume control over Class VI underground injection control (UIC) permitting. CCS proponents have long identified state primacy as a fix for federal Class VI permitting backlogs. The Trump administration has also touted primacy as a signal of increased cooperative federalism and permitting reform, as both goals were announced as part of Administrator Lee Zeldin's "Powering the Great American Comeback" initiative. Even as states increasingly and publicly wrestle to take control and expedite injection well permitting, however, other key legal battlegrounds are emerging that CCS project proponents should be tracking.

UIC Primacy Overview

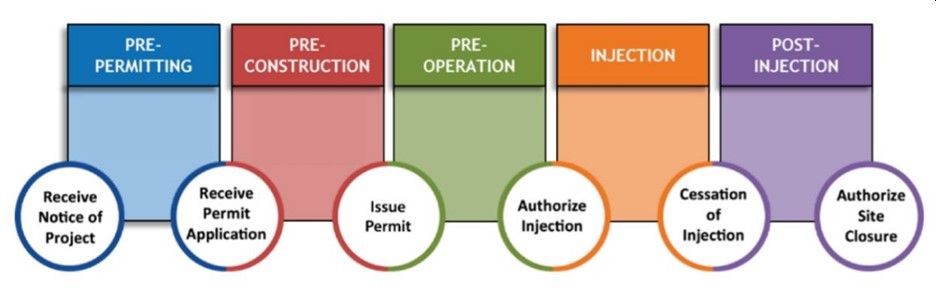

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) establishes requirements and provisions for the UIC program, which is administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and governs the construction, operation, permitting, and closure of injection wells. Under the SDWA, EPA can grant primary enforcement and permitting authority (primacy) over the UIC program to states and tribes.1 In order to obtain primacy, states, territories, and tribes must apply to EPA through its UIC primacy application process, as shown in the below diagram:2

Application process for primacy or program

revision

Class VI wells are used to inject carbon dioxide (CO2) into underground formations for permanent storage (geologic sequestration), as part of CCS. CCS could reduce the amount of CO2 emitted from power plants and other large industrial facilities. Class VI wells require a permit to construct and operate the well through site closure.

State Primacy in the Spotlight

While many states already have primacy over other well classes,3 currently, only four states have primacy for Class VI injection wells. EPA granted primacy to North Dakota in 2018,4 Wyoming in 2020,5 Louisiana in 2024,6 and West Virginia in 2025.7 Arizona submitted an application for primacy in February 2024.

On April 29, 2025, EPA and the Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) took the next step toward Texas assuming primacy with the signature of a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) regarding the administration of Texas programs related to Class VI wells. EPA is evaluating the RRC's formal primacy application submitted on December 19, 2022.8 The MOA is the end of the application phase. Next, EPA will publish a proposed approval of the primacy application, followed by a 45-day notice and comment period and submission of a final rule for the administrator's signature. Until primacy is granted and any appeals are exhausted, EPA Region 6 will continue to have Class VI permitting authority in Texas.9 Of the 19 project applicants currently waiting in the EPA Region 6 permitting queue, 17 are in Texas.

The Louisiana primacy grant is currently being litigated in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. Environmental groups, including Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, Healthy Gulf, and Alliance for Affordable Energy, allege that Louisiana's program fails to meet minimum federal standards by reducing post-injection closure liability, weakening Class VI program requirements, and failing to demonstrate that the state has the requisite staff and expertise to implement the program.10 Oral argument in this case was heard on February 4, 2025,11 and a decision may be forthcoming soon.

Three Less Covered CCS Battlegrounds Taking Shape

CCS proponents have long identified state primacy as a fix for federal permitting delays. Primacy has also been touted as an accomplishment of the Trump administration in its first 100 days. But while primacy dominates the news, less covered legal battlegrounds are forming against the push to scale CCS.

Class VI Permit Appeals

No Class VI injection well permit is viable—no matter who issued it or how fast—unless the permitting authority has complied with UIC regulations. As EPA's regional offices and authorized states inch through their respective permitting queues to grant final permitting decisions, administrative appeals brought by CCS project opponents are beginning to set important precedents that CCS project proponents should be tracking.

In one recent decision, EPA's Environmental Appeals Board (EAB) remanded Class VI permit approvals for a low-carbon ammonia fertilizer plant back to Region 5 for further evaluation.12 EPA Region 5 had approved a 10-year Post-Injection Site Care Plan (PISC) for the project, less than the default 50-year PISC period under UIC regulations. EAB held that Region 5 failed to document in the administrative record how it had exercised its independent judgment in determining that the shortened PISC period would be protective of underground sources of drinking water. Until that error can be corrected on remand, CO2 injection remains unauthorized.

Environmental Impact Reviews

EAB also recently reaffirmed that UIC Class VI permitting decisions are exempt from environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).13 Other federal permitting or funding actions may still trigger NEPA review for some CCS projects, but EAB's holding is nevertheless reassuring.

In California, however, environmental groups have sued to stop the state's first-ever approved CCS project for alleged failures to comply with environmental review requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Kern County certified an Environmental Impact Report and approved entitlements to the Carbon Terravault I project, which proposes a 46-MMT capacity CCS project within the Lost Hills oil field. The environmental groups' complaint includes numerous allegations of noncompliance with CEQA, including failure to adequately disclose, assess, and mitigate the project's environmental impacts with respect to air quality, energy use, pipeline hazards, biological resources, and water supply, among others. If the case proceeds to a decision on the merits, the outcome would provide the first true precedent for assessing the legal adequacy of environmental review for a CCS project in California.

Pipeline Controversies

Deployment of CCS at scale will require construction or repurposing of pipeline networks for CO2 to be transported from carbon capture projects to sequestration sites, especially when it comes to nascent CCS "hubs." One high-profile project in the Midwest proposes to connect ethanol plants in five states to a CO2 sequestration site in North Dakota. South Dakota's Public Utilities Commission voted in April to deny the project sponsor's route permit application, just one month after South Dakota's legislature passed and the governor signed a ban on the use of eminent domain for CO2 pipelines in the state. Iowa legislators are currently considering a similar eminent domain ban. Elsewhere in Louisiana, environmentalists have sued state environmental agencies, alleging they lacked authority to execute a CO2 storage and pipeline agreement for a pipeline proposed to run through a state wildlife management area. Still, in other states (such as California), intrastate CO2 pipelines remain banned entirely pending Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration's (PHMSA) adoption of federal safety standards.14 Emerging controversies over CO2 pipelines are reminiscent in some respects to the myriad legal challenges that arose from opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline and the delays faced by transmission projects that interconnect renewables to the electric grid.

Conclusion

The regulatory framework for CCS and related infrastructure remains both complex and highly dynamic. Legal and regulatory disputes continue to arise. As CCS initiatives expand, proponents must be prepared to navigate an intricate landscape marked by shifting administration policies and priorities, federal and state rules, active litigation, and persistent public resistance.

Endnotes

1. Safe Drinking Water Act, 42 U.S.C. 300h-1, 300j-9; 40 CFR Parts 144, 145, and 146.

2. 40 C.F.R. Part 145. The EPA has issued two guidance documents that describe the procedures for the EPA's review and approval for primacy and program revision applications. See Memorandum from Victor J. Kimm, Director, Office of Drinking Water to Water Division Directors Regions I-X, Guidance for Review and Approval of State Underground Injection Control (UIC) Programs and Revisions to Approved State Programs; Env't Protection Agency, Guidance for State Submissions under Section 1425 of the Safe Drinking Water Act, Ground Water Program Guidance #19.

3. Currently, 37 states and three territories have assumed primacy over the arguably similar Class II program. Primary Enforcement Authority for the Underground Injection Control Program, U.S. EPA.

4. State of North Dakota Underground Injection Control Program; Class VI Primacy Approval, 90 Fed. Reg. 10,691 (Apr. 24, 2018).

5. Wyoming Underground Injection Control Program; Class VI Primacy, 85 Fed. Reg. 64,053 (Oct. 8, 2020).

6. State of Louisiana Underground Injection Control Program; Class VI Primacy, 89 Fed. Reg. 703 (Jan. 5, 2024).

7. West Virginia Underground Injection Control (UIC) Program; Class VI Primacy, 83 Fed. Reg. 17,758 (Feb. 26, 2025).

8. Texas, Class VI UIC Primacy Application (Dec. 19, 2022).

9. EPA issued its first UIC Class VI permits for three wells in Texas on April 7, 2025. See Press Release, EPA Issues Final Permits for Geologic Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide in Texas, Env't Protection Agency (Apr. 7, 2025); see also Project Details, Env't Protection Agency.

10. See Brief for Petitioner at *1, Deep S. Ctr. For Env't Justice v. Env't Protection Agency, No. 24-60084 (5th Cir. June 12, 2024).

11. ECF No. 138, Deep S. Ctr. For Env't Justice v. Env't Protection Agency, No. 24-60084 (5th Cir. Feb. 4, 2025).

12. In re Wabash Carbon Services, LLC, 19 E.A.D. 128 (EAB 2025).

13. Id. at 147 (citing in re Powertech (USA) Inc., 19 E.A.D. 23, 40–42 (EAB 2024)).

14. Cal. S.B.905 (2022). PHMSA issued a notice of proposed rulemaking on revisions to the Pipeline Safety Regulations to include safety standards and reporting requirements for gas- and liquid-phase carbon dioxide pipelines on January 15, 2025. The proposed rule was withdrawn from publication on January 20, 2025, under Presidential Memorandum on Regulatory Freeze Pending Review, which required all federal departments and agencies to withdraw any rules that had been introduced but not published.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]