- within Employment and HR topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Business & Consumer Services industries

- within Employment and HR and Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

INTRODUCTION

Remote work is one of COVID-19's enduring legacies. What began as something necessary for health and safety has become a fairly conventional practice. As the O.E.C.D. notes:1

Increasingly, some individuals are able to, and choose to for personal reasons, carry out all or part of their work for an enterprise of a Contracting State from a place in the other Contracting State * * *.

Not surprisingly, the O.E.C.D.'s latest update to its Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital addresses implications of cross-border remote working.

This article recounts existing guidance on a remote worker's effect on his or her employer and follows with an explanation of the new enhanced guidance.

EXISTING LAW AND PRIOR GUIDANCE

Permanent Establishment Under Income Tax Treaties

Under the general pattern of income tax treaties, one treaty partner country ("Contracting State 1") may tax the business activities of a resident of the other treaty partner country ("Contracting State 2") if that resident's business activities are derived through a permanent establishment ("P.E.") located in Contracting State 1.2

In broad terms, a P.E. is defined as a fixed place of business through which a business is partly or wholly carried on.3 Typically included as examples are places of management, branches, offices, factories, workshops, and mines.4 Excluded are places where ancillary and preparatory activities occur. Examples of the latter are fixed places for (i) the storage display or delivery of goods, (ii) the purchase of goods or the collection of information, or (ii) for the performance of preparatory or auxiliary activity.5

Even if a corporation based in Contracting State 2 has no physical facility in Contracting State 1, a P.E. can exist through the presence of an agent. In some circumstances, the activity of a person acting in Contracting State 1 on behalf of an enterprise of Contracting State 2 can constitute a P.E. in Contracting State 1 if the person (i) habitually concludes contracts or (ii) habitually plays the principal role leading to the conclusion of contracts that are routinely concluded in the name of the enterprise without material modification by the enterprise, and the underlying contract6

- is in the name of the enterprise,

- relates to the transfer of property owned by the principal,

- relates to the granting of rights to use property that the principal has the right to use, or

- relates to the provision of services by the principal.

In the foregoing way, income tax treaties raise the threshold before Contracting State 1 can impose tax on business income derived by a resident of Contracting State 2 that is derived from business activities that take place in Contracting State 1. To illustrate, U.S. domestic law allows the U.S. to impose tax on a foreign enterprise if it is considered to be engaged in a U.S. trade or business that generates U.S. source business income – the presence or absence of a P.E. is largely irrelevant when determining whether tax is due in this fact pattern.7 A foreign person is considered to be so engaged if its business activities are "considerable, continuous, and regular."8

Prior O.E.C.D. Guidance

As the updated commentary notes, analytical issues arise because a remote worker typically works from premises that are "not a premises of the enterprise [who employs the worker] nor the premises of another enterprise with contractual or other connections * * * such as a customer, supplier, or associated enterprise."9 Instead, a remote worker typically works out of his or her home, a second home, a rental facility, the home of a friend or relative, or other similar facilities.

The O.E.C.D. previously stated that whether premises can be a P.E. depends partly on whether the premises are at the disposal of an enterprise. With respect to remote workers working out of their homes, the O.E.C.D. stated that intermittent or incidental work at a worker's home does not constitute a P.E.10 However, continuous use of the home office combined with an employer requirement for the worker to use his or her home, including by not providing the worker with an office when one is required, can cause the home office to be viewed as being at the disposal of the enterprise.

By contrast, a worker who chooses to work from his or her home in one country instead of using the office made available in the enterprise's country does not cause the worker's home to be at the disposal of the enterprise.

In 2021, the O.E.C.D. released updated guidance relating to a variety of tax issues in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.11 The guidance indicated that remote work caused by public health measures should not create a P.E., because (i) the work site was temporary, (ii) the work was carried out at a home that was not at the disposal of the employer, and (iii) in the absence of public health measures, the work could be carried out at offices provided by the employer.12 And while an employee who continued to work from home after no longer being required to do so for public health reasons created permanence to the use of his or her home, the O.E.C.D. also indicated that other facts were necessary to support a view that the home constituted a P.E.

Similarly, with respect to a P.E. caused by dependent agents, the O.E.C.D. believed that an employee with contracting authority should not be viewed as habitually exercising that authority in another country if the employee's presence in that country was forced by government measures.13 The result could differ for employees working abroad prior to government-mandated lockdowns and employees working abroad afterwards.14

As much of this guidance focused on the unique circumstances arising from the pandemic, further guidance was needed with the normalization of non-COVID-related remote work.

NEW GUIDANCE

The new guidance does not change the language of the treaty, but it revises the O.E.C.D.'s commentary to Article 5.15 The updated commentary emphasizes that general principles for determining the existence of a P.E. – such as the permanence of the premises and whether the premises are used to carry out core business functions rather than ancillary functions – apply in evaluating whether the employer, a resident of Contracting State 2, maintains a P.E. in Contracting State 1 by reason of a home office of an employee located in Contracting State 1.

The new guidance is largely divided between two factors: time spent working out of a remote worker's home and commercial reasons for being in another country.

Time SpentThe commentary focuses on whether the place is a fixed place and whether the place is used on a regular basis. The O.E.C.D. anticipates that, in many cases, business activities will be carried out at a home in Contracting State 1 by an employer based in Contracting State 2 only intermittently or incidentally, which would not cause an employee's home in Contracting State 1 to be a place of business for the enterprise.16 However, the use of a home in Contracting State 1 on a continuous basis for an extended period of time may indicate that the home of the employee in Contracting State 1 is a place of business for an enterprise based in Contracting State 2.

The O.E.C.D. also anticipates that in most cases, a home in Contracting State 1 will not be considered a place of business for an employer based in Contracting State 2 if less than 50% of the employee's working time is spent at home.17 By contrast, an employee who spends 50% of more of his or her working time at home in Contracting State 1 could cause the home to be treated as a place of business for his or her employer in Contracting State 2, depending on facts and circumstances.18 While actual conduct controls, contractual arrangements can provide supporting evidence for the calculation of working time.19

Commercial Reasons

The O.E.C.D. takes the view that the presence or absence of commercial reasons for an employee to be in another country is a prominent consideration in determining whether the employee's home office constitutes a P.E.20 If a commercial reason does not exist, then an employee's home cannot be a place of business for the employer, and therefore not a P.E. unless facts and circumstances indicate otherwise.21 A commercial reason generally exists where the use of an employee's home facilitates an enterprise's business activities.22 A relevant factor in the analysis might be whether an employer, in the absence of an employee working from home, would find other premises in that employee's country. Presumably if a location in Contracting State 1 would exist in any event, the home office of the employee in Contracting State 1 merely substitutes for a fixed place of business.

Specific examples of commercial reasons include situations where an employee's presence in a country facilitates any of the following:23

- Meeting with customers

- Cultivating new customers or identifying business opportunities

- Identifying new suppliers or managing relationships with suppliers

- Real-time interactions, including remote ones, with customers or suppliers in different time zones

- Consulting relevant experts, such as university researchers

- Collaborating with other businesses

- Performing services for customers that require physical presence

- Interacting with fellow employees

As with the time factor, intermittent or incidental activities do not create a commercial reason for an enterprise based in State 2 to have an office in Contracting State 1.24 These include short, occasional visits to a customer or relatively minor engagements with a customer. Additionally, the mere presence of customers or suppliers in the same country as the employee's home is not a commercial reason.25

An employer might allow remote work for incidental reasons. For example, remote work might be a job perk, or an employer might want to cut costs such as office rental expense in Contracting State 2.26 Such reasons are not commercial reasons.

Where there is no commercial reason for undertaking the activities related to the business of an enterprise formed in Contracting State 2 from a home or other relevant place located in Contracting State 1, that place would not be a place of business of the enterprise, unless other facts and circumstances indicate otherwise.27

Finally, if an employee of an enterprise based in Contracting State 2 is the only person or the primary person conducting business for an enterprise in Contracting State 1, such as a consultant on an extended assignment,28 the consultant's home in Contracting State 1 is a place of business for her employer in Contracting State 2.29

Examples

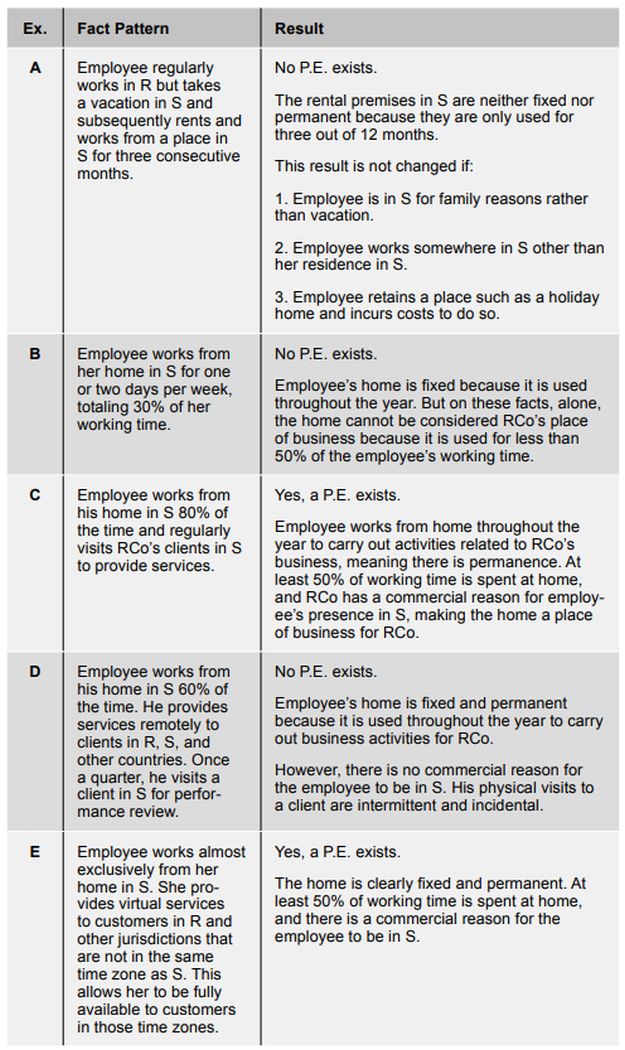

Para. 44.21 of the updated commentary provides five examples featuring an employee who works for RCo, an enterprise of R, a treaty country, in S, another treaty country. The examples are summarized below.

CONCLUSION

Several broad comments may be made regarding the O.E.C.D.'s update:

- They do not cover the full breadth of P.E. For example, there is no mention of auxiliary or preparatory activities that are common specifically to remote work, which would not by themselves create a P.E.

- The discussion focuses entirely on P.E.'s created by fixed places of business rather than through the activities of agents.

- The general statements and conclusions are so broad and so careful to provide exceptions if the facts require a different conclusion that tax authorities in two separate jurisdictions can find justification for reaching contradictory conclusions in the same fact pattern.

Nonetheless, the updated commentary provides more concreteness to the norms of a post-COVID world.

Footnotes

1 O.E.C.D. Model Tax Convention Commentary on Art. 5 ("Commentary") Para. 44.1.

2 O.E.C.D. Model Tax Convention ("Treaty") Art. 7 Para. 1.

3 Treaty Art. 5 Para. 1.

4 Treaty Art. 5 Para. 2.

5 Treaty Art. 5 Para. 4.

6 Treaty Art. 5 Para. 5.

7 Code §882.

8 Pinchot v. Commr., 113 F.2d 718 (1940).

9 Commentary Para. 44.1.

10 2017 Commentary Para. 18.

11 "Updated guidance on tax treaties and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic." O.E.C.D. (2021) ("COVID Guidance").

12 COVID Guidance Para. 16.

13 COVID Guidance Para. 21.

14 COVID Guidance Para. 22, 23.

15 See Commentary Para. 44.1-44.21.

16 Commentary Para. 44.7.

17 Commentary Para. 44.8.

18 Commentary Para. 44.10.

19 Commentary Para. 44.9.

20 Commentary Para. 44.11.

21 Commentary Para. 44.19.

22 Commentary Para. 44.12.

23 Commentary Para. 44.17.

24 Commentary Para. 44.14.

25 Commentary Para. 44.18.

26 Commentary Para. 44.15, 44.16.

27 Commentary Para. 44.19.

28 Commentary Para. 44.20.

29 The Commentary says that different considerations apply in such circumstances, although it appears that many of the listed activities and factors would also apply here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]