This past week, the internet lit up over whether it was okay for President Biden and the First Lady to order the same dish at the Red Hen. In this issue, we invite you to read the February highlights on clean labeling false advertising litigation, updates on green claims, thoughts on whether light beer should taste like beer, FDA's plant-based milks draft guidance, and USDA's enhanced authority on "organic" claims with the same level of fascination.

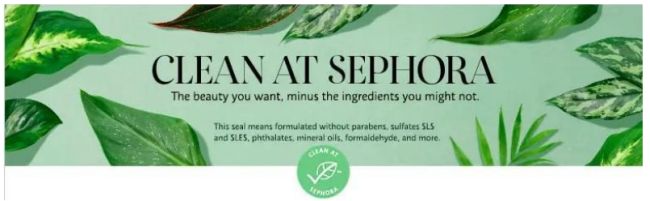

"Clean at Sephora" Motion to Dismiss A Test for the Reasonable Consumer Standard

Clean claims on foods, supplements, OTC drugs and cosmetics have surged in popularity as have retailers' efforts to curate product selections and ingredients to eliminate disfavored ingredients, such as synthetic dyes, preservatives, fragrances, parabens, phthalates, etc. "Clean" is not defined in regulations, which means that each brand or retailer must explain to shoppers how it's defined within that brand. In fact, many popular lifestyle-related terms – vegetarian, vegan, keto, cruelty-free, etc. – also are not defined by regulation.

To the delight of advertising lawyers and the chagrin of marketers, the answer to the question of how to deal with potentially vague terms is through clear and conspicuous disclosures. It is just this scenario that is at issue in a pending false advertising lawsuit, Finster v. Sephora USA Inc.

On November 11, 2022, Lindsey Finster and a purported class of consumers filed a lawsuit against Sephora USA Inc. in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York, alleging that Sephora's "Clean" cosmetics—sold under its "Clean At Sephora" program—are deceptively advertised as "clean," where the products "contain ingredients inconsistent with how consumers understand" the word "clean." Finster alleges that consumers were therefore misled into believing that the products being sold were neither synthetic nor "connected to causing physical harm and irritation." Plaintiffs allegedly purchased "Clean At Sephora" believing that the products were not harmful or synthetic. In support of her allegations, Finster lists several allegedly synthetic and potentially harmful ingredients in the products designated "Clean At Sephora." As a result, Finster asserts claims for violations of state consumer fraud acts, deceptive acts and unlawful practices pursuant to NY GBL §§ 349, 350, fraud, unjust enrichment, breach of implied and express warranties, and violations of the Magnuson Moss Warranty Act.

On February 2, 2023, Sephora moved to dismiss these claims, claiming that Finster "transform[s] the phrase 'Clean at Sephora' into something completely different," that is to say, "Natural at Sephora," and ignores the fact that "Sephora prominently explains, in plain terms, exactly what it means by the phrase." Given Sephora's transparency as to what "Clean At Sephora" means, Sephora claims that consumers could not plausibly be confused by the phrase. Finster, according to Sephora, makes no allegations that Sephora's "Clean At Sephora" definition "is not prominently displayed or is not, in any sense, being met." Sephora goes on to defend that the "Clean At Sephora" seal means "formulated without parabens, sulfates SLS and SLES, phthalates, mineral oils, formaldehyde, and more," and the label does not say that these "products contain only natural ingredients."

We have no connection to this case but it's one we're watching closely, and here's why: This case is a litmus test for the "reasonable consumer" standard. Based on the sample above, Sephora took reasonable steps to clearly and conspicuously disclose what "Clean at Sephora" means in close proximity to the claim. Sephora makes clear that "clean" is associated only with a list of excluded ingredients. It is not reasonable for consumers to assume that it means anything else. If the court finds that Sephora's disclosure was not sufficient, the litigation risks could ripple across "clean" brands everywhere.

Further, given that "clean" is not defined in regulations, is used differently across brands and retailers, and is a term that is not specific to cosmetics or even consumer products, it seems a stretch to believe that any class of consumers could have a common understanding of "clean" sufficient to form a class. Finster may survive a motion to dismiss, but we're holding out hope that Sephora comes out clean in the end.

NAD + FTC

Whitens...without the harm? NAD also reviewed the use of an undefined term – "harm" – in the context of teeth whitening products. P&G challenged Oral Essentials, Inc., ("OEI") maker of Lumineux Whitening Strips relative to the following claim: Clinically proven to whiten as well as the leading brand...without the harm.

Setting aside the product efficacy review, NAD was concerned that "harm" conveys a safety-related message that P&G's product could damage teeth. OEI's declaration supported that tooth sensitivity and gum irritation are associated with peroxide bleach, as used in P&G's product. However, because these symptoms are generally mild and self-resolving, and because the American Dental Association has determined that P&G's Crest whitening strips are safe for consumer use, NAD determined that "without the harm" conveyed a safety message for which OEI did not provide substantiation.

Net Zero by 2040? Tell me how. NAD also doubled-down on parsing environmental claims to discern whether advertisers actually have plans to achieve their lofty environmental goals or whether these are merely lofty ESG-themed aspirations. JBS – the second-largest food company in the world – made several aspirational claims about its commitment "to be net zero by 2040" on its website, social media, newspapers, YouTube, and publicly accessible corporate reports. Those claims were challenged by the Institute for Agriculture & Trade Policy ("IATP"), who argued that the claims convey an unsupported message that "JBS has an operational plan in place to achieve its net zero goals and is implementing such a plan." NAD acknowledged that JBS had made a "significant preliminary investment" toward reducing emissions, that it had "undertaken steps to begin learning" how to address the operational and scientific challenges it will face, and that these steps "may be helpful towards achieving net-zero by 2040." Nevertheless, NAD found that these steps were not enough to "support the message conveyed by the claim." NAD thinks the message is "that JBS has a plan it is implementing today to achieve net zero operational impact by 2040." Check out our group's full post here. Relatedly, as part of its Green Guides update, the FTC is conducting a public hearing regarding "recyclable" claims on May 23rd.

Light Beer Should Taste Like Beer...And finally, NAD considered a Molson Coors ad in which athletes are celebrating the completion of a difficult workout by opening a can labeled "Extremely Light Beer" and pouring the liquid over their heads while an announcer says "Light beer shouldn't taste like water. It should taste like beer."

Anheuser-Busch filed a challenge using NAD's Fast-Track SWIFT process, arguing that the videos falsely disparage Michelob Ultra and other light beers by claiming that consumers find them to taste like water. Molson Coors pointed out that no competitors were named and the tagline was simply "a subjective opinion about what beer should and should not taste like, which cannot be objectively proved or disproved." In other words, mere puffery "because it is not sufficiently specific and material enough to create expectations in consumers." But NAD didn't agree. It deemed Coors' claim measurable and objective and found it to be unsupported by evidence.

Really? Crack open a beverage of choice and check out our group's concerns about what this says about the line between puffery and objectively provable claims here.

FDA + USDA

- USDA announced a final rule intended to strengthen enforcement on production, handling, and sale of organic agricultural products, which is effective March 20, 2023. As food producers and retailers know, "organic" production may involve multiple links in a supply chain. The new rule is intended to close gaps in prior regulations by requiring National Organic Program ("NOP") import certificates for imported products, clarifying NOP's oversight role, and reduce the types of entities that operate in the organic supply chain without USDA oversight. While the final rule focuses on supply chain and enforcement, labeling is also impacted. The final rule includes provisions intended to clarify calculation of organic content in a multi-ingredient product.

- FDA announced that the agency intends to exercise enforcement discretion for certain qualified health claims involving high flavanol cocoa and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

- FDA also released its "Labeling of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives and Voluntary Nutrient Statements" draft guidance. The draft guidance leans heavily on consumer understanding of plant-based products being different from dairy milk and allows for plant-based products to be labeled as "milk" and recommends that those plant-based products that feature "milk" in their names also include a voluntary nutritional comparison statement. The comment period is open until April 24, 2023.

- Related to the plant-based milk draft guidance, FDA also released its list of guidance topics it plans to issue in the upcoming year here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.