- within Transport topic(s)

Key Takeaways

- Apple's 27% off-app commission, restrictive link placement, and deceptive conduct with the court led to a finding of civil contempt, financial penalties, and a referral to the U.S. Attorney for potential criminal sanctions.

- Apple's perjury and over-designation of documents as privileged damaged its credibility with the court, highlighting the need for businesses to be transparent in legal proceedings.

- Apple's new policies were seen as a willful violation of the original injunction and an effort to construct new barriers to competition.

- The court focused on the App Store's market dominance and Apple's internal documents showing exclusionary intent, signaling that competition cases will closely examine both factors.

- Platforms and developers should use this opportunity to evaluate their restrictions, or the restrictions they face, against Apple's experience.

Overview

The recent sanctions against Apple in Epic v. Apple1 are the latest development in the long saga over Apple's App Store policies. Following an order enjoining certain restrictions Apple placed on app developers, Apple developed new policies and restrictions, which they argued were consistent with the injunction. These new policies and their business rationale were evaluated in court following a motion to enforce the injunction by Epic. The court held two hearings on the matter, and between these hearings, Apple's privilege claims over certain documents were determined to be invalid. The newly produced documents shed light on Apple's decision-making and past statements in court. Ultimately, the court found Apple had willfully violated the injunction, immediately enjoined Apple's new restrictions, imposed civil contempt penalties, and referred the case to the U.S. Attorney's Office to investigate whether Apple should be held in criminal contempt.

The sanctions ruling provides insights into the type of platform restrictions that may run afoul of unfair competition laws. Theories based on similar restrictions may be tested in future antitrust cases by both class and private plaintiffs. These cases, however, will remain fact-intensive inquiries that consider, for example, whether a platform has market power and the rationales for various rules or restrictions.

Overview of Initial Injunction

Following a May 2021 trial, Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rodgers of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California found Apple had engaged in anticompetitive conduct by forbidding off-platform links for applications that utilized the App Store. The court likewise found that Apple's 30% payment processing fee for on-platform purchases was not tied to the value of its intellectual property (IP) and "allowed [Apple] to reap supracompetitive operating margins." The court enjoined Apple from continuing to forbid off-app links, noting that "a remedy to eliminate the [restriction against links] is appropriate," but declined to "micromanage" Apple's business operations. Instead, the court allowed Apple to determine and adopt policies consistent with this injunction, believing that competition from off-app purchases would price discipline Apple's 30% commission.

Apple's Post-Injunction Restrictions

In the new sanctions order, the court determined Apple purposefully hid documents showing it considered two options for complying with the injunction: (1) no commission for off-app purchases but considerable limitations on link placement and (2) a 27% commission for off-app purchases. The court determined Apple ultimately chose "the most anticompetitive option: a link entitlement program that included both the placement restrictions of Proposal 1 and the 27% commission from Proposal 2." The court then analyzed the individual components of this policy:

- 27% commission. Apple's 27% commission was

not limited to purchases made directly after a click-through.

Rather, Apple's policy required the commission on any digital

goods and services transactions on the developers' website made

within seven days of the click-through, regardless of whether those

purchases were made on an iPhone. The court noted that this fee was

nearly identical to the 30% fee for in-app purchases, which the

court found was not tied to Apple's IP and allowed it to reap

supracompetitive profits.

- Apple's documents demonstrated they determined a no-commission policy would potentially cost the company billions in revenue and designed the commission to ensure link-out purchases were "not economically viable."

- Restrictions on link placement, content, and other

practices designed to increase consumer friction. Apple

considered giving app developers more freedom in designing and

placing in-app links, but again "chose the most aggressive,

anticompetitive option" by adopting policies specifically

designed to decrease utilization and increase consumer friction.

Apple's internal analysis, again, showed these were designed to

maximize their revenue. The court broke these restrictions into

four categories:

- Link placement. Apple significantly restricted where developers could place their links within an application. The court found restrictions that forbid links from appearing anywhere users could purchase digital goods and services—e.g., an in-game store allowing the purchase of cosmetics—particularly problematic.

- Link design. Apple only permitted developers to use

"plain button style" links rather than "developer

styled links," which significantly reduced the likelihood

consumers would utilize the links. Images from the court's

opinion, which were taken from Apple's documents, illustrate

the difference.

- Purchase-flow friction. Apple's documents

indicated it sought to maximize instances where a user does not

complete a purchase to ensure developers "reach[ed] a tipping

point where they lose more on linking out than they would sticking

with Apple [in-app purchases] and the higher commission."

(Quotation from Apple's internal analysis). The court focused

on two such features:

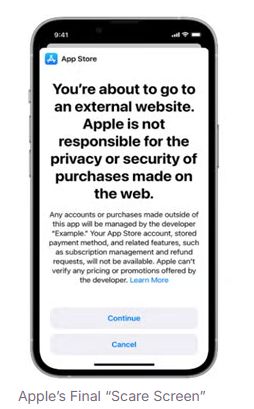

- Scare screen. Apple developed and instituted a

pop-up warning, which it referred to as a "scare screen,"

to dissuade consumers from following through to the external

website. Before reaching its ultimate decision, Apple considered

three options and "again, [] chose the most anticompetitive

option." The court found Apple's internal documents

illustrated their intent; examples from the opinion include:

- "By continuing on the web, you will leave the app and be taken to an external website" because "'external website' sounds scary, so execs will love it." (Apple Document)

- "To make your version even worse you could add the developer name rather than the app name." (Apple Document)

- "If we want to 'scare' users a bit, i like the

addition of 'out' because it raises questions and hesitancy

haha. out? out where? omg what do i do?" (Apple

Document)

- Static URLs. Apple's restrictions forbid the use of dynamic URLs, which are URLs that can change and send users to different sites depending on the user or their behavior. For example, a dynamic URL could send a user to the developer's webpage with the user already logged into their account. Static URLs, in contrast, can only send users to one specific site and do not allow features like autologin or linking to a site based on the user's pre-click activity within an app. The court found this restriction was placed on developers to further increase consumer friction and reduce developer adoption.

- Calls-to-action ban. Apple proscribed the text that could proceed links by providing five options. Under this requirement, developers could not write their own text, such as "unlock special subscription content if you subscribe on [our website]." Internal documents demonstrated that Apple determined allowing calls to action would increase off-app purchases by between 5% and 25%.

- Exclusion of certain developers. Apple offers certain categories of developers lower commission rates for in-app subscriptions on their platform. For example, video and news developers can join Apple partner programs that offer developers 15% commissions rather than the standard 30%. Under Apple's new policy, any developer that utilized in-app links for out-of-app purchases would no longer be eligible for the Apple partner programs, which would subject them to the 30% commission for purchases on Apple's platform. The court found that losing access to the reduced commission for in-app purchases ensured none of these developers would utilize in-app links to enable out-of-app purchases.

- Scare screen. Apple developed and instituted a

pop-up warning, which it referred to as a "scare screen,"

to dissuade consumers from following through to the external

website. Before reaching its ultimate decision, Apple considered

three options and "again, [] chose the most anticompetitive

option." The court found Apple's internal documents

illustrated their intent; examples from the opinion include:

Apple's Deceptive Conduct With the Court

The court held two hearings related to Apple's post-injunction conduct. During the period between those hearings, Apple was ordered to produce numerous documents it had previously claimed were privileged. These documents indicated that many of Apple's previous statements in court were false; for example, the court found an Apple executive perjured himself in the initial hearing. The executive testified in the first hearing that Apple's 27% commission was the result of a 2024 report by an external consultant; however, documents produced between the hearings showed Apple made its policy decisions in 2023—before the report was commissioned. The court also found that Apple had willfully over-withheld documents for privilege. Apple attempted to blame the privilege assertions on its document review vendors, but the court was unconvinced and noted that the privilege errors "flow[ed] in one direction."

The Court's Ruling

The court found Apple had willfully violated its injunction and immediately and permanently enjoined Apple from:

- Imposing any commission or any fee on purchases that consumers make out of an app

- Conditioning developers' style, language, formatting, quality, flow, or placement of links enabling purchases outside of an app

- Prohibiting or limiting the use of buttons or other calls to action, or otherwise conditioning the content of links to enable out-of-app purchases

- Excluding certain categories of apps and developers from utilizing links for in-app purchases

- Using anything other than a neutral message apprising users that they are going to a third-party site

- Restricting developers' use of dynamic links

The court also held Apple in civil contempt for its perjury and "abuse of attorney-client privileged designations to delay proceeding and obscure its decision-making process." As a penalty, Apple was ordered to pay for the full amount of the special master's review of Apple's privilege claims and Epic's attorneys' fees related to the privilege dispute. Finally, the court referred the matter to the U.S. Attorney's Office for potential criminal sanctions against Apple and one of its senior executives.

Takeaways

The court's ruling provides insight into the type of restrictions that may run afoul of unfair competition law, but that should not imply there is a one-size-fits-all approach. Two factors permeated almost all of the court's analysis: (1) the power of Apple's App Store and its growing dominance in digital goods and services transactions; and (2) Apple's documents, which painted a clear picture of its exclusionary intent. Nonetheless, the court's ruling and other recent developments related to app restrictions provide valuable insights to platforms and developers:

- Court deference to business decisions. This ruling should not imply that courts are likely to start requiring platforms to adopt specific policies as this court imposed on Apple. Rather, the decision reflects the court's frustrations with Apple's conduct. Following issuance of the first injunction, the court appears to have expected that additional competition by off-app purchasers would price discipline Apple's supracompetitive commissions. It was only when Apple erected new barriers to such competition that the court became directly involved in setting policies.

- The view from Europe. Legal risk related to platform restrictions is not limited to the United States, as this ruling has some echoes in Europe. A week before the judgment, Apple was fined €500 million (~$565 million) by the European Commission for failing to comply with its obligation under the EU Digital Markets Act to permit app developers distributing their apps via the App Store to inform customers, free of charge, of alternative offers outside the App Store, steer customers to those offers, and allow them to make purchases. The European Commission found that a number of restrictions imposed by Apple prevent developers from fully benefiting from the advantages of alternative distribution outside the App Store and deprive consumers of alternative and cheaper offers that developers could otherwise inform consumers about. The Commission ordered Apple to remove the technical and commercial restrictions that it had imposed. Apple has 60 days from April 23, 2025, to provide the European Commission with a description of the measures that it has taken to ensure compliance.

- Privilege review and documents.In addition to lessons about app restrictions, the ruling emphasizes the importance of normal course documents and thoughtful privilege review. Apple's defeat was largely predicated on its documents and overly aggressive privilege assertions—both of which undermined its credibility with the court.Privilege reviewsare often left to vendors, with quality checks only being applied to documents not marked privileged in first-level review. Structuring a review in this way increases the risk of finding yourself in a position similar to Apple—where your credibility with the court is undermined and you leave yourself exposed to potential sanctions. Businesses should proactively work with their counsel to make sure reviews are developed in a way that ensures privilege designations and review protocols are defensible. This will require some additional work on the front end, but it can significantly reduce costs and risk over the course of a case.

Footnote

1. Epic Games, Inc. v. Apple Inc., Case No. 4:20-cv-05640-YGR (N.D. Cal 2020).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.