- within Energy and Natural Resources topic(s)

- in United States

- in United States

- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

The emergence of SAF was described in a recent speech by the UK's Chancellor of the Exchequer as a "game changer". It is anticipated that the aviation sector's increasing deployment of SAF may enable the expansion of UK airport capacity, notwithstanding previously perceived restrictions on the development of that infrastructure given net zero targets. This would also require growing a SAF production industry.

The Government's aim of having at least five SAF plants under construction in the UK by 2025 will not be achieved, but it has put in place a "SAF Mandate" designed to guarantee a demand for this nascent fuel, and is legislating for a "revenue certainty mechanism" to stimulate SAF production and supply, as well as allocating grant funding for new SAF projects.

This article considers the opportunities for private funds and others to invest in the SAF market arising from the regulatory measures being introduced which will, it is hoped, support the construction of large-scale SAF production facilities in the UK.

What is SAF?

SAF is "drop-in" fuel that can be blended with conventional aviation kerosene. As SAF can be used in existing engines with no modification needed, it is expected to be the primary energy source for reducing airlines' carbon emissions.

It is an umbrella term for fuels made from a variety of feedstocks and production methods. Each are at different stages of development, broadly categorised as:

- first generation SAF, already manufactured at commercial scale, comprising of hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA), which is fuel developed from oil or fats, notably, used cooking oil;

- second generation SAF, non-HEFA, including various methods of making advanced fuels from wastes and residues, such as municipal solid waste; and

- third generation SAF, known as "power-to-liquid" aviation fuel, made from low carbon power sources, such as renewable energy.

SAF is not zero carbon. As with the aviation kerosene it is mixed with, SAF emits carbon when burned in aeroplanes. However, its production methods can deliver significant overall life cycle carbon reductions, estimated to be potentially up to 80% lower, together with other environmental benefits, compared to using conventional fossil-based fuel supplies.

Why SAF?

The UK has an established legal commitment under its national climate change legislation to bring greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050, compared with 1990 levels.

The aviation sector is a major contributor to such emissions. In 2022, international and domestic aviation was reported to account for 7% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the UK and this share was anticipated to increase, as passenger numbers are expected to grow, to 9% in 2025, 11% in 2030 and 16% in 2035.

The technological challenges of electrification of the aviation industry, or the use of hydrogen as an alternative fuel, means that such other solutions are far from being usable. SAF, however, is now used in commercial flights and is one of the only realistic, scalable ways to decarbonise this sector.

"SAF Mandate" – guaranteeing demand

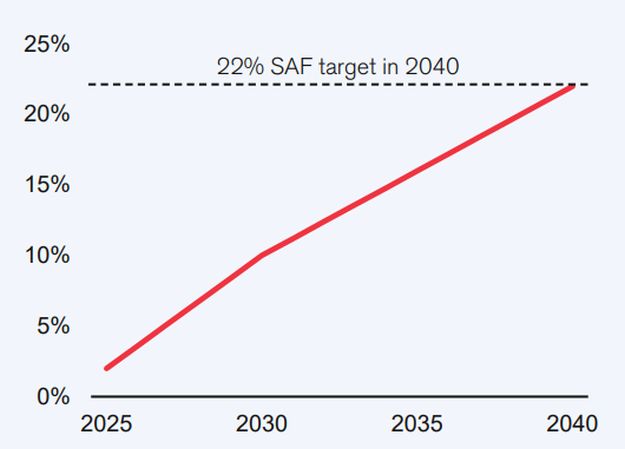

The "SAF Mandate" came into force at the start of 2025 and is the Government's main policy mechanism for securing demand for SAF. It imposes a legal obligation on fuel suppliers in the UK to supply a growing proportion of SAF, starting at 2% in 2025 and increasing linearly each year to 10% in 2030 and 22% in 2040, with any subsequent target subject to further review.

Fuel suppliers are rewarded certificates for the SAF they supply, issued by the Government regulator, based on the level of carbon reduction that it is calculated to deliver.

The SAF Mandate and revenue certainty mechanism are designed to turn a policy ambition into a private investment reality.

SAF mandate year-on-year increase, 2025-2040

These certificates are used to evidence compliance with the SAF Mandate; or, if a supplier exceeds its required proportions, they can be traded via an online reporting platform where certificates may be transferred between registered accounts.

Alternatively, a supplier could instead pay a penalty under a buy-out mechanism, which sets the maximum cost for discharging its obligation.

Eligibility for receiving such certificates includes the requirement that all SAF must achieve minimum emission reductions of 40% relative to conventional kerosene fuel sources, as well as having to satisfy industry technical specifications and sustainability criteria for relevant feedstocks (for example, any SAF derived from food or feed crops is excluded).

In prioritising waste-based and advanced feedstocks, limits are imposed on the extent to which HEFA can be used to satisfy a supplier's obligations under the "SAF Mandate". HEFA is currently the main source of commercially available SAF, but its eligible volume share will decrease to 71% in 2030 and 35% in 2040. On the other hand, there is a separate obligation to incentivise "third generation" powerto-liquid fuels, although the percentage requirements for suppliers will be much smaller, reaching 3.5% by 2040, given that its production is at an early stage of development and is relatively costly.

These obligations under the "SAF Mandate" fall on UK fuel suppliers delivering at least 15.9 terajoules (approximately 468,000 litres) of aviation turbine fuel per year. Their required proportions of SAF must be sourced ultimately from the businesses producing it.

Supporting UK production and supply

While the "SAF Mandate" should mean growing market demand for SAF, it is recognised this of itself may not be enough to encourage private sector investors to finance the development of new production sites for emerging SAF technology at the necessary commercial scale.

As summarised in the Government's own recent public policy consultation response paper: "For production facilities, making the leap from lab to commercial scale has proven difficult as smaller demonstration facilities are capital intensive and often unprofitable. Commercial plants can then typically cost £600m to £2bn to reach economies of scale and tend to run at a loss during their first years of deployment. First-of-a-kind plants often struggle to secure major investment from equity and debt providers due to a number of associated risks, including revenue certainty."

Key risks for investing in building new plants and their bankability were identified. These risks include the lack of any clear pricing signal for advanced (non-HEFA) SAF (given that it is likely to be significantly more expensive to produce than currently established aviation fuels) and that such projects might often be competing for finance with other low carbon technologies.

The Government is therefore legislating to introduce a "revenue certainty mechanism" to support SAF production and supply in the UK.

The core feature of this revenue certainty mechanism is a "guaranteed strike price", delivering more stable revenue streams for SAF project financing. It is expected to follow the precedent set by the "contracts for difference" used to support renewable electricity projects. A government agency agrees a predetermined price for how much a SAF producer will be able sell its product for, with the difference between that price and what the producer ends up selling it for on the market at the time of production then being settled under this mechanism, either to compensate the producer for any lower price achieved or for it to pay back any excess profit.

The underlying workings of such mechanism will need to be confirmed, but the Government has indicated the first tranche of these revenue support contracts will be for the benefit of UK projects that produce SAF using non-HEFA technology and feedstocks.

Other measures already instigated by the Government to support the growth and stabilisation of the SAF production industry in the UK, in addition to the "revenue certainty mechanism", include awarding over £100m in grant funding for testing and development of new technologies and processes, courtesy of programmes and initiatives like the "Advanced Fuels Fund" and the "UK SAF Clearing House".

When UK production of lowcarbon fuels is up and running, it could support up to 15,000 green jobs, contribute £5 billion a year to our economy, and deliver clean and secure energy. What is more, fulfilling the SAF mandate could save up to 2.7 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year by 2030.

Heidi Alexander, Secretary of State for Transport

Site-level implementation

Developing SAF production facilities carries higher risks for investors given the nascent technology and the high levels of capital expenditure expected to result from the largescale nature of such operations. It is a complex process and will require obtaining planning permission and a bespoke environmental permit for the use of the site for its new production activities, as well as complying with operator safety requirements for handling potentially large quantities of hazardous substances under the "Control of Major Accident Hazards" (COMAH) regulations, all of which will require multi-layered and detailed site assessments and applications to Government authorities. Anticipated build times, based on experience of developing industrial plants of equivalent size and complexity, would be several years or more.

Private capital – removing barriers to investment

While private markets funds have invested in SAF businesses, investment has so far been limited.

As outlined above, SAF production capacity is currently in short supply, which can be challenging for investors, with the lack of an embedded skilled workforce and given that the industry is yet to achieve significant economies of scale and any proven steady income stream. Moreover, SAF is derived from a range of feedstocks and production methods and each comes with different technological challenges and development needs. This level of uncertainty has held back private market investors looking to invest in tried-and-tested technology with reliable business earnings.

However, the SAF Mandate and revenue certainty mechanism provide core policy levers which, together, are expected to drive up demand, stabilise revenues, and raise production capacity. This should in turn provide the scale and track record for SAF to enter the investible universe of mainstream private capital managers, both directly and indirectly (e.g. in businesses training SAF workers and other supply chain investment opportunities).

Additionally, many private capital managers have sustainability-focused investors, and it is possible a SAF business investment may align with their environmental impact objectives.

SAF has the potential to be on the cusp of scalability – but without revenue certainty and a faster planning regime, private capital could remain on the sidelines.

Concluding remarks: building UK capacity

Subsequent to the Chancellor's speech, mentioned above, official figures are reported to show that 90% of SAF deployed by UK aeroplanes during last year came from used cooking oil imported from China. Only a further 2% of SAF was produced in the UK. Other jurisdictions are also actively competing for access to increasing volumes of SAF – for example, under the European Union's own corresponding scheme, the "ReFuelEU Aviation Regulation", which similarly mandates increasing SAF blending requirements. It is therefore imperative that the UK is proactive in supporting building its own domestic capacity.

As originally contemplated under the previous UK Government administration's "Jet Zero Strategy", the primary aim of which was to achieve net zero aviation, it will be incumbent on the current Government to continue encouraging the UK aviation sector to modernise its operational management, and for it to deliver on wider international initiatives associated with, for example, emissions trading and offsetting, including the interface between the UK 'Emissions Trading Scheme' and the ICAO's 'Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation' (CORSIA).

More immediately, to attract the necessary degree of finance and investment from private capital funds and other project stakeholders, the Government will need to drive forward the domestic policies outlined in this article. Having introduced the "SAF Mandate", it is essential to bring into legal operation the SAF "revenue certainty mechanism" on competitive terms for producers. Given the timeframes for building multiple large-scale plants, it is of most importance that the processing of SAF development site permits and all other administrative hurdles is addressed responsively to establish a mature UK industry.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]