Financial regulation in the UK – How will the new structure work?

It is understandable that regulation is in the spotlight, given the scale of the financial crisis and the strains it has potentially placed on the public purse. But it is not only regulatory policies and supervisory practices that are under scrutiny. So too are the regulators themselves, and the structures in which they operate.

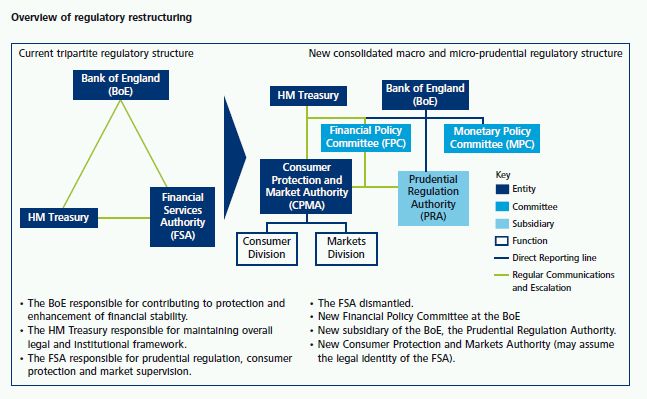

This is most clearly seen in the UK. In June, the Chancellor announced that the FSA would cease to exist in its current form, and would be replaced by a new Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), which would be a subsidiary of the Bank of England, and a "powerful new" Consumer Protection and Markets Authority (CPMA). Systemic risk would be addressed by a Financial Policy Committee (FPC) at the Bank of England. He indicated that the transition would be complete by 2012.

On 26 July HM Treasury issued a consultation paper, entitled "A new approach to financial regulation: judgement, focus and stability". It gave further details of the proposals, with a separate consultation on whether to create a single agency to tackle serious economic crime.

The new structure is set out in the diagram on the following page.

Key issues Transition

Many of the important issues in any restructuring relate to the transition. In this particular case there is a risk that the essential tasks of reforming policy, agreeing it internationally, and implementing it effectively will be disrupted by these changes. There are also personnel and systems issues, both in splitting the FSA into two or more units and in integrating the arrangements of the PRA with those of the Bank of England, and the need to consider whether to "grandfather" existing authorisations and permissions.

Although the need to address these issues is widely understood, the success or otherwise of the project will depend on how well they are tackled in practice.

Structural issues

But not all of the issues relate to the transition. There are also questions about how these arrangements will work in the longer term.

These can be grouped under four headings: governance; scope and possible overlaps; objectives of each agency; and relations with others.

a) Governance

The governance issues relate to each of the new bodies – the PRA, CPMA and FPC.

In his Mansion House speech, the Chancellor said it was only central banks that had the broad macroeconomic understanding and authority needed to make macroprudential judgments. Moreover, in order to manage crises effectively, they needed to be familiar with the institutions they dealt with, and "so they must also be responsible for day-to-day micro-prudential regulation as well."

As a result the PRA will be a subsidiary of the Bank of England, with a board chaired by the Governor, and will implement the macro-prudential decisions of the FPC. But in all other respects the Treasury paper states that the PRA will have operational independence for the day-to-day regulation and supervision of firms, with a majority of non-executives on its board, and with the Bank having no formal power of direction over it. It remains to be seen how this will work in practice.

Moving on to the CPMA, the Government proposes an operationally distinct and "strong" markets division to lead on all market conduct regulation, and represent the UK in the European Securities and Markets Authority. However, this separate identity is not buttressed by any independent board or corporate structure, so it is as yet uncertain how this will operate.

Finally, it is unclear whether the FPC will be a "Committee of Court" – i.e. with non-executive membership entirely comprised of those already on the board of the Bank of England – or whether it will follow the same model as the Monetary Policy Committee, where the independent members do not serve on the main board.

b) Scope and overlaps

The Treasury paper describes the FSA as "monolithic", arguing that prudential and conduct-of-business supervision require different skills, approaches and cultures. Nevertheless, others have noted that the theoretical advantages of an integrated supervisory model are considerable, and the PRA and CPMA will need to share information and collaborate in as effective a fashion as possible to achieve these synergies, and reduce both over and under-laps. Moreover, some small firms will not be supervised by the PRA for prudential purposes, giving scope (in theory at least) for some inconsistency here.

In the past, some commentators suggested that giving an independent central bank responsibility both for monetary policy and financial supervision risked too great a concentration of power, and/or a lack of focus on (or conflict between) one or other function. While the potential for conflicts may have been overstated, the Bank and PRA still need the capacity to operate effectively across this wide range of roles, which is daunting given the variety of decisions that prudential supervision entails.

c) Objectives of each agency

The Treasury paper describes the CPMA as a "strong consumer champion" although it notes that the Financial Ombudsman Scheme will only be credible if it does not favour, or appear to favour, consumers. Given its powers to act against firms, the CPMA too needs to show that its rules and actions are balanced and proportionate. Whether this can easily be done as "consumer champion" remains to be seen.

Rather different issues arise with the FPC. Until the macro-prudential tools it will deploy have been identified in more detail, it will be difficult to decide whether its objectives are unduly ambitious or not.

More generally, it has not yet been decided whether to supplement each body's primary objective with secondary factors, such as competitiveness or innovation. If so, should these considerations be subservient to the primary objective (which would make the regime less flexible, but clearer) or should an alternative approach be adopted?

d) Relations with others

Clearly UK regulators need to interact effectively with opposite numbers overseas. This issue is addressed in the Treasury paper, and there is no reason to believe that the new arrangements cannot be made to work effectively.

But it will also be important for the CPMA and PRA to work together so that firms do not face clashes in terms of data requirements, meeting requests, supervisory demands and so on. In other words, effective relationship management with the industry will be important to the success of the new structure.

Conclusion

The Government has stated its commitment to a full and comprehensive consultation on these proposals. It is likely that many of the issues discussed above will feature in these discussions.

Beyond Basel III: The FSA recommends further major changes to the capital regime

"Since the financial crisis began in mid-2007, the majority of losses and most of the build up of leverage occurred in the trading book", so wrote the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in January 2009. The Committee went on to acknowledge that shortcomings in its capital framework for market risk – unchanged since its introduction in 1996 – had been an important contributory factor and announced a two stage plan of corrective action:

Stage 1: this involved correcting or mitigating a number of specific deficiencies it identified in the framework and was completed in July 2009 for implementation by 1 January 2011. Key measures taken at this stage included introducing a stressed value at risk (VaR) requirement, extending the scope of the incremental risk charge to cover rating migration risk, and requiring most securitisation positions to be subject to banking book capital requirements.

Stage 2: recognising the partial nature of the steps taken at stage 1, the Committee announced that it would be "initiating a longer-term, fundamental review of the risk-based capital framework for trading activities".

Although the Committee has not itself said another word on the matter, our own FSA – unsurprisingly given the importance of banks' trading activities to London – has not let the idea of a fundamental review drop. In March 2009, the Turner Report called for "a more radical review of trading book risk measurement and capital adequacy requirements" to be conducted at international level and completed within one year. While this target date is long past, the FSA has not been idle, with its work culminating in a substantial discussion paper in August, "The prudential regime for trading activities – A fundamental review".

As Basel III and the Banking Commission assume centre stage, the paper is probably in danger of not receiving the attention it merits. That would be unfortunate as it is important, for two main reasons. First, it raises the question whether fundamental weaknesses in the prudential regime for trading activities remain, even after the July 2009 amendments. Whatever the answer ultimately reached, it is better that it is reached after proper consideration. Secondly, in offering thoughts on how the prudential regime for trading activities may be strengthened, the paper is relevant to the question of whether those activities should be separated from the utility functions of banking and hence, to the work of the Banking Commission set up by the coalition government in the UK.

Despite its title, which may suggest that it is only relevant to banks and investment banks with a trading book, the paper also contains proposals relevant to banks and building societies which do not engage in trading.

This is because the scope of the paper goes beyond the trading book as currently defined, including, for example, consideration of the need for market risk capital charges for banking book positions.

The remainder of this article summarises the main issues raised in the discussion paper together with the FSA's recommendations. The paper addresses three main areas:

- valuation;

- the coverage and coherence of the capital regime; and

- risk management and modelling.

The main points of the FSA's analysis of each topic are summarised below.

a) Valuation

The FSA suggests that there are three main issues that need to be tackled given that valuation gains and losses, in the absence of prudential filters, directly impact regulatory capital (and generally core tier 1) and thus affect a bank's ability to leverage.

Inconsistency

The FSA refers to Bank of England research which showed large differences between the valuations of super-senior tranches of collateralised debt obligations (CDO) by six large banks at the end of 2007. In particular, the valuation range was many times (12 to 35 times!) the capital requirement of 1.6% of the par value of the notes. Other areas of variation noted include credit valuation adjustments (CVA), notably in relation to monoline insurers but also to other market counterparties, and bid-offer adjustments both of which FSA attributes to limited guidance from the accounting authorities.

Other sources of inconsistency identified are that firms use different accounting categories for the same instruments and differences between US GAAP and IFRS.

The FSA's key conclusion is that "ensuring comparable valuations across firms can be just as important, if not more so, as applying comparable capital requirements.

Uncertainty

The underlying problem identified is the existence of positions – for example, positions which are illiquid, highly concentrated or in complex financial instruments – for which there are a range of plausible valuations. The FSA notes that regulators have not agreed on how to feed such uncertainty into capital measures.

Procyclicality

The general issue identified is that mark-to-market accounting potentially allows firms to build up leverage when market values are high, exacerbating asset bubbles. In addition, specific concerns are noted regarding aggressive valuation practices for bid-offer adjustments and CVA calculations.

The FSA's broad conclusion is that: "The prudential framework should moderate aggressive valuation practices where these can be identified and quantified, especially with a view to reducing procyclicality in the upswing."

The FSA's recommendations on valuation – Summary

- A Pillar 1 capital charge to capture valuation uncertainty.

- Robust guidelines to ensure firms adopt prudent valuations.

- A system of regulatory valuation adjustments to ensure a greater consistency in balance sheet valuation approaches.

b) Coverage and coherence of the capital regime

The FSA identifies a number of items which it sees as significant inconsistencies, gaps or shortcomings in the framework for determining capital requirements. These concern the treatment of credit risk, market liquidity risk, interest rate risk on amortised cost positions, credit valuation adjustments and other risks not captured at all or not captured adequately.

Credit risk

The FSA notes that there is a structural difference between the credit markets and other financial markets, namely that a greater proportion of credit risk is retained within the financial sector. Firms hedging their credit risk tend to transfer the risk to another financial institution rather than to a non-financial firm. Hence in the case of credit risk, the incentives to hedge contained in the trading book capital regime may not be justified from a systemic standpoint.

As regards default risk, the FSA observes that the same factors drive it irrespective of valuation approach or management's intent in holding a position. Hence, there is a case for having a consistent approach across all credit positions.

With respect to using modelling in the capital framework for credit risk, the FSA notes that the crisis revealed major shortcomings in the modelling techniques used, for example underestimates of correlations, and therefore identifies a number of possible alternatives to full modelling, namely:

- continuing to allow credit risk to be modelled but subject to a floor or cap based on stress testing;

- severe restrictions on using models to determine capital requirements for credit risk but modifying the standard rules to allow more recognition of netting; and

- a consistent set of standard rules to calculate default risk on all credit assets, irrespective of valuation approach, with separate standard rules for credit spread risk.

The FSA notes that although the risk drivers of default risk are the same irrespective of how assets are valued, valuation approach does affect credit spread risk. In the case of fair valued assets, but not assets valued at amortised cost, changes in credit spread directly impact shareholders' funds. Hence, the FSA concludes such assets should be subject to a market risk capital charge, even if held in the banking book. This would be a departure from the current framework which only imposes a credit spread risk charge on fair valued assets in the trading book. Currently, banking book assets which are fair valued are not subject to such a charge.

Market liquidity risk

This is the risk of drastic price changes as a result of sudden variations in asset and derivative market liquidity. The FSA says that there are issues with the inclusion of illiquid instruments in the current regulatory trading book and expresses the view that the market risk capital standards should be related to liquidity/trading feasibility in adverse market conditions.

Interest rate risk on amortised cost positions

Currently, interest rate risk in the banking book is dealt with only under Pillar 2. The FSA proposes to publish a discussion paper in Q4 2010 which will consider the case for imposing a Pillar 1 capital requirement on at least some elements of this risk.

Credit valuation adjustments

The FSA sets out three possible options for a "more coherent" approach to calculating capital for CVA volatility, namely (1) standard percentages applied to current CVA to capture a worst-case change in credit spreads or exposures; (2) standalone VaR/incremental risk charge (IRC) of CVA i.e. running the firm's CVA measures through VaR and IRC frameworks; and (3) joint simulation of CVA with other market and credit risk factors.

Other risks not captured at all or not captured adequately

The FSA identifies three risks which have proved to be sources of material losses in the last three years and which it believes ought to be captured, or better captured, in the regulatory capital framework. These are:

- contingent market risk, i.e. the market risk created by the non-performance or loss of a hedge counterparty (e.g. Lehman) or set of hedge counterparties (e.g. where a few firms hedge a certain risk and a significant proportion of them abruptly decide to provide the hedging service no longer);

- gap risk, i.e. a market move leading to a sudden discontinuity in the price of a position which is not captured by 99% confidence interval VaR; and

- hedging risk, i.e. the risk of increased hedging costs in periods of protracted volatility (which is not captured by VaR models).

The FSA suggests stress testing may have a role to play in dealing with some of these risks

The FSA's recommendations on coverage and coherence of the capital regime – summary

- Have a consistent regulatory approach to credit assets.

- Consider a range of options for capturing the credit risk on fair valued assets better.

- Capture market liquidity risk in regulatory capital requirements.

- Link valuation and capital requirements and in particular require market risk capital for all fair valued positions.

- Consider Pillar 1 capital charge for interest rate risk on amortised cost assets.

- Develop a coherent approach to capturing CVA volatility.

- Capture contingent market risk, gap risk and hedging risk

c) Risk management and modelling

The FSA addresses the need for improvements in firms' management of risk in their trading activities. In addition, it discusses weaknesses in firms' risk modelling and raises the question whether firms' internal risk models should remain part of the regulatory capital framework.

Risk management

The FSA makes three main points:

- there continues to be a need for firms to strengthen their valuation processes and controls, particularly with regard to complex products;

- regulators need to apply higher risk management standards before granting permission to trade in a class of instruments rather than before permission model approval is granted (the crisis provides significant examples, such as CDOs, where there were inadequacies in the risk management of positions subject to standard, not model calculated, capital requirements);

- regulators' current risk management standards do not place sufficient emphasis on the responsibility of front office senior management, failing to recognise that "independent control functions are less effective in operations where the culture of front office is to elude or evade those controls".

Risk modelling

The key question raised is whether internal models should continue to play a role in the regulatory capital framework given that using internal models for regulatory capital purposes may create an incentive for firms to underestimate risk and given that the practice ignores the basic rationale for prudential regulation, namely that firms are likely to mis-price systemic risks.

The FSA outlines five possible ways of mitigating the risks posed by using internal models in the regulatory capital framework, namely:

- further research into better modelling approaches for those risks not captured by 10 day 99% VaR (e.g. expected tail risk models);

- using simple and transparent approximations to measures based on complex mathematical models (e.g. scenario matrix approaches);

- using cruder measures as back-stops to full modelling approaches, for example complementing any internal models approach for complex products with a robust stress-testing framework;

- achieving greater international consistency in approving and implementing internal models through a technical expert group established by the Basel Committee; and

- lowering the differential between requirements under standard rules and those based on model calculations in order to make the removal of model recognition a realistic possibility.

The FSA's recommendations on risk management and modelling – summary

11. Extend risk management standards and delink them from model approval.

12. Make a full, co-ordinated assessment of risk measurement approaches for trading activities.

13. Make increased and better use of stress testing in the capital framework.

14. Improve international consistency in the application of risk modelling standards.

15. Ensure cancellation of model approval is a credible threat

What are the next steps?

Comments on the paper are requested by 26th November. The FSA plans to use that feedback at Basel where the Fundamental Review is, it says, now being developed internationally.

Convergence on financial instruments accounting: still in the balance.

Convergence in the area of financial instruments accounting has featured in the plans of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) since the roadmap for convergence between the US GAAP and IFRS was put in place under the Memorandum of Understanding in 2006. Thereafter, the push for convergence of financial instrument accounting was put in the spotlight as a result of the financial crisis. Since then the two standard setters have been working steadily towards this goal, in some cases through joint Board meetings, in other cases through each Board developing and exposing their own ideas and considering whether a converged outcome can then be arrived at. The latest update on convergence, which includes financial instrument accounting, came in the form of a document released on the 24 June 2010 with the lengthy title of "Progress Report on Commitment to Convergence of Accounting Standards and a Single Set of High Quality Global Accounting Standards". The chart on the next page provides more detail of the IASB and FASB's intentions in this area over the next 2-3 years.

Classification and measurement: divergent proposals

Most significantly it was confirmed that, in the wake of the IASB and FASB modifying their convergence strategy, the efforts to put in place a successor standard to IAS 39 are seen as one of a small number of "major" projects that will be given priority in terms of completion by the end of the second quarter of 2011. Yet, convergence between both Boards on a new financial instruments standard is some way off.

For the classification and measurement of financial assets only, the IASB published in November 2009 "IFRS 9 Financial Instruments". This is a final standard though it is not endorsed for use in Europe yet. The corresponding guidance on classification and measurement of financial liabilities is still to be finalised as the IASB are digesting the comments received on their Exposure Draft "Financial Liabilities: Fair Value Option". This proposed that for financial liabilities designated at fair value through profit and loss, changes in fair value due to credit risk would be recognised in equity. Whilst the Board continues to deliberate on this subject, there is overwhelming support among respondents for the model proposed.

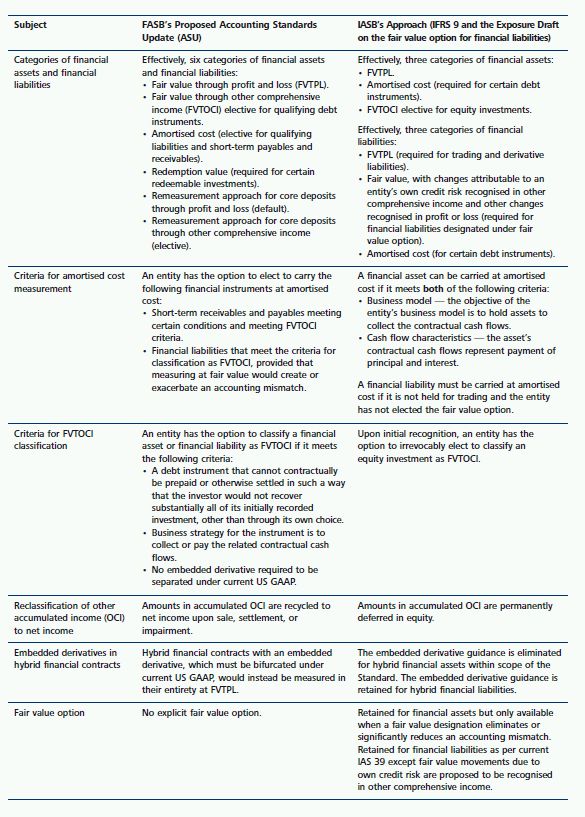

The FASB's proposals for the classification and measurement of financial instruments formed part of the proposals in the comprehensive exposure draft issued in May 2009. It is interesting to note that whilst there are areas in which the requirements would be equivalent, there are also significant areas where the two models would give very different results in terms of classification and measurement. A high level comparison of some aspects of the two models is shown in the table on the next page.

As can be seen from the table, the FASB model has a higher number of measurement categories, which may attract attention of respondents in terms of relative complexity of the model. At a high level the dividing lines between the measurement categories of fair value through profit and loss (FVTPL), fair value through other comprehensive income (FVTOCI), and amortised cost are drawn differently under the two models.

In particular, in comparison with the IASB model the FASB's proposals are more restrictive in terms of instruments eligible for amortised cost measurement, particularly with respect to financial assets. As far as financial institutions are concerned, IFRS 9 would permit many plain lending arrangement assets held to collect contractual cash flows to be measured at amortised cost whereas the FASB's model would not. The greater ability for amortised cost accounting under the IASB model are likely to be a feature of comment letters received by the FASB who may come under pressure to make changes in this area.

Impairment: feedback on two models

The two Boards also produced differing proposals in the area of impairment of financial assets. Impairment of financial assets is only relevant to debt instrument assets measured at amortised cost under the IASB approach and only relevant to short-term receivables at amortised cost or debt instrument assets measured at FVTOCI under the FASB approach.

The IASB proposed in their Exposure Draft a full expected loss approach. The expected loss model attempts to capture the forecast expected losses at the date the asset is recognised by having a lower interest income than the interest under the contract. The incorporation of expected credit losses in the initial amortised cost accounting and full anticipation of expected future cash flows means that this approach is radically different from the current incurred loss model in IAS 39. The alternative FASB model is arguably somewhere in between the expected loss and incurred loss model. It shares with the expected loss proposals of the IASB the fact that there is no trigger or probability threshold for recognition of impairment with credit impairment, which is recognised when the entity does not expect to collect all contractual amounts due for originated financial assets, and all amounts originally expected to be collected for purchased financial assets. However, it differs from a full expected cash flow method in so far as an entity is required to consider the impact of past events and existing conditions in assessing collectability, but is not required to forecast future events or economic conditions that do not exist at the reporting date. Also, while the IASB model involves the effective interest rate being adjusted initially to exclude a margin for initially expected credit losses, the FASB approach does not involve such an adjustment except in the case of purchased financial assets with initially expected credit losses (e.g. an acquisition of distressed debt).

In considering the responses to the two proposed models in this area, the Boards will also draw on the work of the Expert Advisory Panel (EAP), set up to look at the operational aspects of the credit impairment models. A team comprising of bankers, regulators, audit firms, and some IASB members and staff completed six scheduled meetings with the EAP during the IASB's public consultation period for their exposure draft. A summary of the EAP discussions which go into considerable detail in terms of the practical implications of implementing an expected loss approach, is available on the IASB's website.

At their meeting on 24 August, the IASB began in earnest to redeliberate the area of credit impairment. At the meeting the Board tentatively decided to move forward using an expected loss impairment approach, having considered the alternatives of an incurred loss approach, fair value approach or IAS 36 Impairment of Assets approach. The IASB also tentatively decided to consider an expected loss approach based on expected losses during the lifetime of the asset rather than a shorter or longer period. The Board considered that using a shorter outlook period for determining expected losses would ignore some credit losses and convey an incomplete picture of profitability and the pricing of the financial assets. Having considered the alternative proposed, the IASB also tentatively decided that entities should consider all reasonable and supportable information (including forecasts of future conditions) when calculating expected losses, which is at odds with the direction the FASB had proposed.

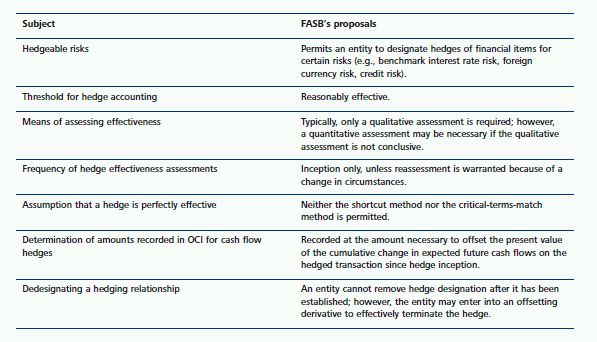

Hedge accounting: FASB proposes simplification with IASB proposals still to come

In the area of hedge accounting the FASB, as part of its comprehensive proposals on financial instrument accounting issued in May of this year, has suggested an approach that is summarised below:

In a number of respects this differs from the current requirements in IAS 39 (de-designation, threshold for hedge accounting, means and frequency of assessment). However, the IASB has been considering revising that model. The IASB is yet to issue its proposals in this area with these due out in the fourth quarter of 2010 with Board discussions ongoing. Some of the more interesting tentative decisions taken by the Board are as follows:

- to permit bifurcation-by-risk for financial items and indicated a leaning toward permitting bifurcation-byrisk for non-financial items.

- to permit designation of derivatives as hedged items in several situations, including the situation when the hedged exposure is a combination of a derivative and a non-derivative.

- to require an approach for fair value hedge accounting under which the fair value changes of the hedging instrument and the hedged item attributable to the hedged risk are taken to other comprehensive income, and any ineffectiveness is transferred immediately to profit or loss.

Again, as some of these are at odds with the FASB proposals it will be interesting to see to what extent the two Boards will be able to arrive at a converged outcome.

Derecognition: no imminent convergence

The convergence agenda also included a project to improve and converge US GAAP and IFRS standards for derecognition of financial assets. In the wake of the financial crisis, separate steps were taken by the two Boards but with the aim of ultimately working towards a converged outcome. In June 2009, the FASB finalised amended and improved requirements on derecognition of financial assets and liabilities. The changes (in particular, the elimination of the Qualifying Special Purpose Entity concept), reduced the differences between IFRSs and US GAAP. The IASB published its proposals in 2009 for a new derecognition model which was subsequently developed in response to the comments of constituents. The model was explicitly based on the concept of control, not risk and rewards, and therefore represented a departure from the present IAS 39 model.

By May 2010 it had become apparent in joint discussions of the IASB's model that the two Boards differed in their views on the appropriate approach. Interestingly, members of the FASB were unconvinced that a move to a more controls based approach to derecognition would be appropriate given their experiences with such models under US GAAP. The IASB had also received comments from National Standards- Setters on the largely favourable effects of applying IAS 39's derecognition requirements during the financial crisis. In light of this, a decision was made by the Boards that their near-term priority should be improving disclosure requirements in this area, not trying to produce a new derecognition model.

The IASB is therefore aiming to finalise shortly improved disclosure requirements that were originally published in 2009 that are similar to recently amended US GAAP requirements. As regards a new derecognition model, the Boards decided to conduct additional research and analysis, including a post-implementation review of the FASB's recently amended guidance in 2012, as a basis for assessing the nature and direction of any further efforts to improve or converge IFRSs and US GAAP. In practice this means that convergence efforts on this front have been put on the back burner until at least 2012. The existing requirements under US GAAP and IFRS will therefore continue to be in force for a number of years to come.

Financial instruments with characteristics of equity: back to the drawing board?

The issue of what is a liability and what is equity was put on the joint agendas of the IASB and FASB in 2006. Progress on the project has been slow. By early 2010, the Boards had jointly developed a proposed comprehensive new model under the financial instruments with characteristics of equity project. This represented an approach that was different to both existing IFRS and US GAAP. External stakeholders that reviewed a staff draft of that proposal raised concerns about the meaning, enforceability, and internal consistency of some of the proposed requirements. As a result of this, in May of this year the Boards decided that more time was required to work through these concerns. As a result the new timeline now envisages publishing an Exposure Draft in the first quarter of 2011, holding public roundtables in third quarter of 2011 and publishing the final standard in this area by the end of next year. This in turn means that the existing requirements in both GAAPs will be used for a number of years to come.

Offset: balance sheet netting of derivatives

The latest addition to the IASB's and FASB's joint efforts on financial instrument accounting is a separate project to address differences in the standards on balance sheet netting of derivative contracts and other financial instruments. Derivatives assets and liabilities with the same counterparty that are entered into under International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) master netting agreements have generally not met the criteria for offset under IFRS due to failing the condition over intention to settle on a net basis. Although the general criterion also exists under US GAAP, an exception to it is made with respect to derivatives entered into under ISDA master netting agreements. Whilst this has always led to material IFRS/US GAAP differences in terms of balance sheet presentation, the issue has come into sharper focus in the wake of the financial crisis and pressure on financial institutions to reduce the size of their balance sheets. The decision to add this item to the Boards' agendas came in response to stakeholders' concerns (including those of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Financial Stability Board).

The Board discussions on this topic have not yet started in earnest. Currently the IASB is surveying financial statement users to get their views on the offsetting of financial assets and liabilities. The survey focuses on whether and how users of financial statements adjust for offsetting of financial instruments. It is intended to help the standard setter better understand what information is useful to users.

Convergence: nearing the finishing line?

The coming nine months will be a crucial period for both the IASB and FASB in putting in place the next generation of financial instruments accounting standards. By mid-2011 the Boards are due to have the final requirements in place which will capture classification and measurement of financial assets and financial liabilities, impairment and hedge accounting. By that point the IASB and FASB will also have issued their joint exposure drafts on offsetting financial assets and liabilities and financial instruments with characteristics of equity. The financial crisis has placed greater focus on the need for global accounting standards and therefore, there will be much interest in whether the two Boards really are able to produce substantially converged solutions.

OTC derivatives reform – A not so quiet revolution

On 15 September 2005, fourteen of the world's largest derivatives dealers were called to a meeting by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to discuss the growing concerns about the operational risks arising from the explosive growth in credit derivatives. Three years later, on 15 September 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection amid speculation that derivatives were bringing about the collapse of the world's financial system. Today, four of those banks have ceased to exist as independent companies; and there has been a sandstorm of opinions, proposals and papers addressing the apparent shortcomings of the OTC market. So what lessons have been learned and where will they lead us?

An accelerated evolution

In its earliest years, the OTC market has been evolving to improve operational practice. The introduction of the ISDA Master Agreement in 1987 under which contracts could be netted represented a major step forwards in mitigating counterparty risk. Similarly, since SwapClear was voluntarily launched in 1999, it has grown to account for more than 40% of the global Interest Rate Swap market. Parallel advances in electronic confirmation, portfolio reconciliation and compression have all made a contribution to improving the operational and credit risk of the OTC markets (if you like, the unwanted by-products of assuming and shedding market risk). What we have observed in recent years, is an acceleration of this process. Not only have the financial institutions been busy making commitments to global regulators coordinated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, but regulators, policy-makers and industry bodies have been churning out research and opinions at an unrelenting pace.

The tools for change

There is broad agreement everywhere about the problems to solve. They can be summarised as lowering credit risk and increasing transparency. When Lehman Brothers collapsed, contagion risk was uppermost in everyone's mind; along with the recognition that without the necessary data, it is impossible to determine the extent of that risk. How you go about solving these problems is where there is significantly greater variety of opinion. In this article, we discuss the main approaches to addressing credit risk and increasing transparency.

Credit risk mitigation

Following their bankruptcy, it took just 18 days for London Clearing House (LCH) to unwind Lehman's $9 trillion swap portfolio, without recourse to the default fund. To global supervisors, this was more than a mere fire drill – it was proof that in volatile markets, contagion risk is manageable when an adequately capitalised central counterparty leads the payout. It is unsurprising, therefore, to observe supervisors putting their weight behind proposals to broaden the take-up of clearing in OTC markets. But despite this convergence, there remain several issues to resolve.

The first is where the line is drawn in eligibility. Despite the obvious interest that regulators have in mandating what gets cleared, we believe that the Central Counterparties (CCP) and their members will have the last word in what is cleared (clearly in dialogue with supervisors). The reason for this is clear – CCPs must be confident about the risks they assume as it is the members that put up the capital for the default fund. Pushing inappropriate products (e.g. illiquid or nonstandard products) through a CCP will only serve to transfer risk away from those qualified to manage it, to a central counterparty ill-equipped in the event of a market shock.

A second major issue relates to the differential capital requirements associated with bilateral versus CCP trades. In order to quicken the uptake of clearing, it is widely expected that there will be a greater incentive to clear trades through a central counterparty through the application of a lower risk weighting for CCP-facing trades; whilst increasing the capital buffers required to back traditional, uncleared derivatives positions. Where the line is drawn to make clearing more attractive is still a matter for speculation, with the Basel Committee working out detailed recommendations.

The third key issue relates to how clearing exemptions for non-financial corporate end-users will apply. The fact that daily margin or collateral calls introduce liquidity risks for end-users appears to have been accepted. In the USA, clearing will not be mandated for non-financial end users. However, while early versions of the Dodd-Frank Act exempted end-users from posting collateral for hedge trades, the final legislation under consideration does not. In Europe, a slightly different approach is being taken, with the European Commision's (EC) consultation on Derivatives and Market Infrastructures. In it, exemptions for clearing are applied at a threshold of materiality, below which disclosure alone would suffice. September was a crucial month as the EC prepared to publish its formal proposal.1

For those trades which cannot be cleared, alternative risk mitigation measures are under consideration. We can expect supervisors to encourage even greater uptake of electronic confirmation platforms; as well as seeking evidence of good risk management practice (including the timely and accurate exchange of collateral).

Transparency

It's easy to see just how useful CCPs are to supervisors, with their enforceable and up-to-the-minute information on trades, values and counterparts. But even the most optimistic authority would concede that not every trade can be cleared. To make up for this, registered trade repositories will receive and publish transaction level data for public and supervisory consumption. At present, global repositories have been established for Credit, Equity and Interest Rate derivatives. The evolutionary path of these repositories is easy to map – (a) more granular data; (b) more frequent submissions and (c) greater coverage of the global markets. However, there are issues to address with each of these.

Disclosing counterparty data for the trades held is a considerable challenge which requires multiple jurisdictions to collaborate on confidentiality. Frequency of submission is relatively straightforward to increase – but only to a point. What we may ultimately find, is a trend for supervisors to turn to operational data sources (such as execution and confirmation platforms) where data is 'golden' and real-time. With regard to global coverage, there is a limit to how many market participants can be forced to disclose their positions. However, given the concentration of business through the global main dealers, it appears that the majority of business can be disclosed through their books alone (as long as inter-dealer business can be identified).

Conclusion

Looking back at the last two years, there has been significant convergence upon the tools to create more resilient markets. Looking ahead another two, the reform agenda has taken shape and the details of the route now lie firmly in the hands of regulators in the USA and Europe to devise. Without doubt, the evolution is finished and the revolution is about to begin.

Footnotes

1. Since going to press, the EC has published its proposal which can be found at http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/index_en.thm

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.