- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- within Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring and Employment and HR topic(s)

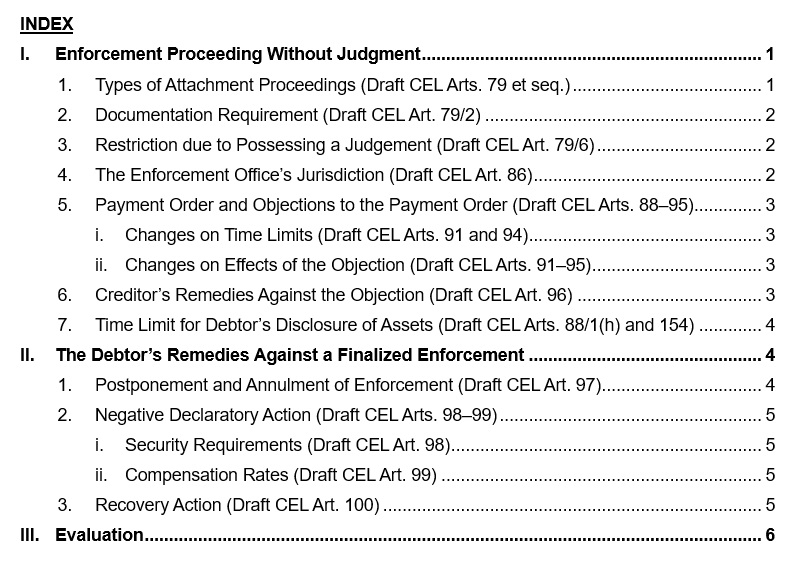

This article constitutes the second part of our series examining the amendments introduced by the Compulsory Enforcement Law (the "Draft CEL"), which is expected to enter into force in 2026. For the first part—addressing the background of the Draft CEL and the amendments concerning the enforcement of judgments, which constitute the core subject of enforcement law in its narrow and technical sense—please see: "The Draft Compulsory Enforcement Law: Enforcement of Judgments and Provisional Attachment"*

This section examines the amendments introduced by the Draft CEL specifically concerning the enforcement proceedings without judgment. It also addresses the novelties relating to other mechanisms that are closely connected to this process, including negative declaratory actions, which play an important role within the overall structure of uncontested enforcement.

I. Enforcement Proceeding Without Judgment

1. Types of Attachment Proceedings (Draft CEL Arts. 79 et seq.)

Under the current regime of the Enforcement and Bankruptcy Law ("the EBL"), an enforcement proceeding without judgment must be initiated for one of these three purposes: attachment,

liquidation of a pledge, or bankruptcy [EBL, Art. 42]. Among these, enforcement aimed at attachment is further divided into three subcategories: (1) general attachment, (2) attachment specific to negotiable instruments, and (3) eviction of leased immovable property [EBL, Arts. 46, 167 and 296]. Additionally, monetary claims arising from subscription agreements ("ASPAK") may also yield to attachment subject to a different procedure under the Law No. 7115.1

The Draft CEL abolishes the distinction between general attachment and attachment specific to negotiable instruments which reportedly "does not provide a meaningful advantage". Furthermore, ASPAK proceedings have been incorporated into the Draft CEL to ensure structural coherence (Draft CEL Arts. 102 et seq.).

1. Documentation Requirement (Draft CEL Art. 79/2)

According to the Draft CEL, the creditor must now rely on a supporting document to initiate an enforcement proceeding without judgment [For comparison, see EBL, Art. 58].

Documents that may serve as the basis for such a proceeding are:

- Document issued or approved by public authorities or competent bodies;

- An instrument—including contracts—capable of proving the legal basis of the claim;

- an invoice uncontested between two merchants.

According to the Commission, this amendment aims to prevent the risks stemming from enforcement proceedings devoid of any written evidence, thereby ensuring a more effective protection of the right to property.

2. Restriction due to Possessing a Judgement (Draft CEL Art. 79/6)

One of the deficiencies under the current EBL concerns the ambiguity as to whether a creditor holding a court judgment may nevertheless initiate an enforcement proceeding without judgment. This ambiguity was resolved by the Court of Cassation's unification of judgments decision on 2017, which definitively forced creditors with a monetary judgment to proceed with enforcement of judgments.2

The Draft CEL expressly incorporates this prohibition into legislation. Furthermore, arbitral awards are also brought within the scope of this prohibition.3

However, the prohibition does not apply to documents that, although not court judgments, nevertheless allow the creditor to proceed as if they were—such as notarial deeds containing an unconditional acknowledgement of debt. In respect of such instruments, the creditor retains the discretion to initiate either enforcement of judgments or an enforcement proceeding without judgment.

3. The Enforcement Office's Jurisdiction (Draft CEL Art. 86)

Under the EBL, the enforcement office's jurisdiction for attachment proceedings was determined by reference to the rules of jurisdiction under substantive law—more specifically, by reference to the Code of Civil Procedure ("the CCP") [EBL, Art. 50]. However, differing from the CCP, the EBL also stipulated an additional rule that granted jurisdiction for the enforcement office located at the place where the contract underlying the claim was executed at.

Seeking to align the legislation with the current legal framework, the Draft CEL removes the place of execution of the underlying contract from the set of reference points used to determine the jurisdiction.

Draft CEL also explicitly provides that where a decision of lack of jurisdiction becomes final, the creditor may request, within two weeks, that the file be transferred to the competent enforcement office. Otherwise, the enforcement proceeding shall be dismissed. The EBL remains silent on this matter; instead, by its reference to the CCP, a two-week period is nevertheless granted to the creditor.

4. Payment Order and Objections to the Payment Order (Draft CEL Arts. 88–95)

Once the enforcement office receives the creditor's request for the proceeding and verifies that it contains the required formal elements, it issues a payment order and serves it on the debtor. The Draft CEL does not introduce any substantial deviation from the EBL regarding the issuance or the elements of the payment order. Rather, the amendments focus primarily on the procedure for the debtor's objection to the payment order.

These amendments appear to be motivated by the objective of maintaining the balance of interests between the parties. Indeed, the draft provisions generally introduce rules in favour of the debtor.

i. Changes on Time Limits (Draft CEL Arts. 91 and 94)

The period for the debtor to object to the payment order has been extended from 7 days to two weeks [EBL, Art. 62]. Additionally, unlike the EBL, the Draft CEL provides that where the payment order is served at multiple addresses upon the creditor's request, the objection period shall begin to run from the latest date of service.

Furthermore, the period for filing a late objection—available to a debtor who was prevented from objecting on time due to an impediment arising without fault—has also been extended. The three-day period under the EBL, which begins once the impediment is removed, has been increased to one week [EBL, Art. 65].

ii. Changes on Effects of the Objection (Draft CEL Arts. 91–95)

A timely objection by the debtor suspends the proceedings and prevents the creditor from initiating attachment without a court judgment.

The debtor may raise objections based on substantive law or enforcement law. At subsequent stages, the debtor will be bound only by objections relating to enforcement law; however, objections based on substantive law may be modified.

Under the current system, the debtor must expressly indicate the amount of the debt to which they object, failing which the objection is deemed not to have been made [EBL, Art. 62/5]. The Draft CEL abandons this presumption and provides that where the debtor does not specify the amount objected to, they shall be deemed to have objected to the entire claim.

5. Creditor's Remedies Against the Objection (Draft CEL Art. 96)

Under the current system, the creditor has two options: removal of the objection before the enforcement court, and cancellation of the objection before the civil courts [EBL, Arts. 68, 68/a, 68/b]. Removal of the objection requires the enforcement court to conduct a formal review limited to enforcement law, whereas cancellation of the objection requires a substantive determination of the existence of the debt by the civil court.

The Draft CEL abolishes the mechanism of removal of the objection entirely, and leaves cancellation of the objection to be the sole remedy available to the creditor. This ensures a higher degree of legal security for debtors.

In addition, the Draft CEL introduces several important procedural amendments to the cancellation action:

- The time limit for the creditor to file a cancellation action—currently one year under the EBL—has been reduced to six months (Draft CEL Art. 96/1).

- The court having the jurisdiction has been clarified as either the court located at the place of the enforcement office conducting the proceedings or the debtor's domicile (Draft CEL Art. 96/2).

- It was stipulated that, when rendering its decision, the court shall consider only the merits of the debtor's objections as of the date the objection was filed. Any payments made by the debtor after the objection shall be taken into account at the enforcement stage by the enforcement office. Accordingly, even if the debtor has made a payment during the course of the proceedings, they will still be exposed to punitive enforcement-denial compensation if their initial objection to the debt was unjustified.

6. Time Limit for Debtor's Disclosure of Assets (Draft CEL Arts. 88/1(h) and 154)

Another amendment introduced by the Draft CEL concerns the period granted to the debtor to submit a statement of assets once the objection period has lapsed or the objection has been cancelled. Under the EBL, this period is seven days [EBL, Art. 60]. The Draft CEL extends this period to two weeks.

II. The Debtor's Remedies Against a Finalized Enforcement

The proceedings shall be finalized if the payment order remained uncontested during the prescribed period, or if the objection is annulled by the civil court.

The Draft CEL introduces some amendments regarding the debtor's remedies following the finalization of enforcement, namely: postponement and annulment of enforcement, negative declaratory actions, and recovery actions. Some of these amendments relate to changes in the legislative structure, while others codify issues that previously arose in practice and were resolved through case law.

This section discusses the amendments applicable to each of these mechanisms.

1. Postponement and Annulment of Enforcement (Draft CEL Art. 97)

The debtor may apply to the enforcement court by submitting documentation showing that the claim forming the basis of the proceedings has been extinguished, has become time-barred, or that the creditor has granted the debtor an extension. In such cases, the enforcement court conducts a formal review and issues a decision regarding the fate of the finalized enforcement, without rendering a judgment with res judicata effect.

The principal document required for the debtor to pursue this remedy is a notary-certified document bearing the creditor's signature.

The EBL also allows the debtor to rely on non-certified documents, provided that the creditor acknowledged the signature. However, EBL does not provide any details on the procedure and evidentiary standard for establishing such acknowledgement.

The Draft CEL adopts the same principle as the EBL. However, it also eliminates this uncertainty in parallel to the Court of Cassation decisions. It provides that the enforcement court shall summon the creditor to a hearing to confirm whether the signature belongs to them. If the creditor denies their signature at the hearing, the debtor's request shall be rejected without further inquiry. If the creditor confirms it or does not appear at the hearing, the debtor's request shall be granted.

2. Negative Declaratory Action (Draft CEL Arts. 98–99)

The debtor may file a negative declaratory action to prevent the initiation of an enforcement proceeding against them, and even to halt the attachment process that has commenced as a result of a finalized enforcement. If a cancellation of objection action is pending simultaneously, the negative declaratory action shall be suspended until the former is resolved.

The Draft CEL rewrites the provisions on negative declaratory actions in a manner partially corresponding to the EBL [EBL, Art. 72], but introduces significant amendments, particularly regarding security requirements and conditions for interim measures.

i. Security Requirements (Draft CEL Art. 98)

The new regulation differs substantially from the EBL with respect to situations in which the debtor is required to provide security when requesting an interim measure.

Under the current legislation, if the debtor requests an interim injunction in a negative declaratory action, the court must order the debtor to provide security of no less than 15% of the claim. Under the Draft CEL, however, the court's discretion is considerably expanded.

Accordingly, if the negative declaratory action (i) is filed before the initiation of enforcement or (ii) is based on the allegation that the claim relies on a forged document, the court may rule that no security is required, or may determine the amount of security at its own discretion.

For actions filed after the initiation of enforcement but does not involve allegations of forgery, the Draft CEL increases the minimum thresholds for securities. The court shall now order the debtor to provide security in the following minimum amounts:

- At least 20% of the claim, where the requested interim measure is to prevent the payment of funds deposited with the enforcement office to the creditor;

- At least 40% of the claim, where the requested interim measure concerns lifting of attachments or suspension of the sale.

ii. Compensation Rates (Draft CEL Art. 99)

Where it is established that the enforcement proceedings or the debtor's objection is based on a forged document, the compensation payable by the party relying on the forgery has been increased. Under the current regime, this compensation is set at no less than 20% of the claim; the Draft CEL raises this threshold to 40% of the claim.

3. Recovery Action (Draft CEL Art. 100)

Where a person who is not actually indebted makes a payment under the threat of compulsory enforcement, the period for initiating a recovery action—previously one year from the date on which the debt was fully paid—has been extended to two years.

The burden of proof placed on the debtor has also been eased. In a recovery action, the debtor is required to prove only that the payment was not owed. Unlike the Turkish Code of Obligations Art. 78,4 the debtor is not required to demonstrate that the payment was made under the mistaken belief of being indebted.

III. Evaluation

The enforcement proceedings not based on a court judgment does not exist in every legal system. With each legislative amendment to date, it has increasingly evolved into a unique, Turkish way of enforcement.

Although this type of proceedings promises swift collection of the claim without the need for judicial litigation, this expectation is never fulfilled in practice; the dispute invariably becomes the subject of judicial proceedings, triggered by the debtor's simple objection.

The Draft CEL refrains from introducing a radical reform such as completely abolishing this type of proceeding. Instead, it seeks to streamline the proceedings itself and the primary and ancillary legal mechanisms associated with it. For instance, the enforcement procedure specific to negotiable instruments, and one of the remedies available to the creditor against the debtor's objection—removal of the objection—has been abandoned.

At the same time, the Draft CEL relaxes certain rules alternately in favour of the debtor and the creditor. For example, the objection periods have been extended to the benefit of the debtor, while the creditor's period to file a cancellation of objection action has been shortened. Conversely, to the creditor's benefit, the security amounts required from the debtor in negative declaratory actions have been increased subject to certain stipulations.

Footnotes

1. See the Law No. 7115 on the Procedure for Initiating Enforcement Proceedings for Monetary Claims Arising from Subscription Agreements.

2. See the Court of Cassation Plenary Assembly on the Unification of Judgments' judgement with the case number of E. 2017/2, K. 2017/3, dated 26 May 2017,

3. See the Draft Compulsory Enforcement Law Art. 79 reasoning.

4. See, Turkish Code of Obligations Art. 78: "A person who voluntarily performs an obligation that they do not owe may reclaim it only if they prove that the performance was made under the mistaken belief of being indebted".

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.