IT'S WIDELY RECOGNIZED THAT THE ROLE OF RENEWABLES IN THE GLOBAL GENERATION MIX IS RISING, REFLECTING THEIR INCREASINGLY LOWER COSTS AND IMPROVED RELIABILITY, SUPPORTED BY CHANGING POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS. THIS ARTICLE ASKS THE QUESTION WHETHER AFRICA NEEDS GAS TO COMPLEMENT ITS GROWING RENEWABLE ENERGY SECTOR?

Africa saw an 8.4% increase in installed renewable energy in 2018 to reach some 46 GW, tempered somewhat perhaps by the fact that in 2017, all new non-hydro power plant projects were fuelled by fuel oil, diesel or coal 1. The share of renewables in meeting global energy demand is expected to grow by one-fifth in the next five years to reach 12.4% in 2023.

However, with Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding Nigeria, South Africa and Angola) expected to grow economically by 4% in 2019, rising to 4.8% in 2021 in line with forecasts, and given the continent's large and growing population, energy demand is expected to nearly double by 2040.

IRENA has forecast 2 that Africa could meet nearly a quarter of its energy needs from indigenous and clean renewable energy by 2030 with renewables amounting to 310 GW, providing half the continent's total electricity generation capacity. This would amount to a sevenfold increase from the capacity available in 2017 (42 GW). However, Sub-Saharan Africa currently has the lowest energy access rates in the world, with less than half its population having access to electricity (falling to less than one-quarter in rural areas). This has a significantly negative impact on economic growth and sustainable development.

Although access to electricity generated from renewable sources (historically hydropower but increasingly solar and wind) will continue to play a key part in increasing energy access, and technological advances in renewable energy will continue to expand options for increasing access to those not served or underserved by national grids, according to Africa50 however, Africa's energy future "necessarily" includes natural gas 3. The scale of the electrification challenge means that more than one source of fuel will be required to achieve the objective 4.

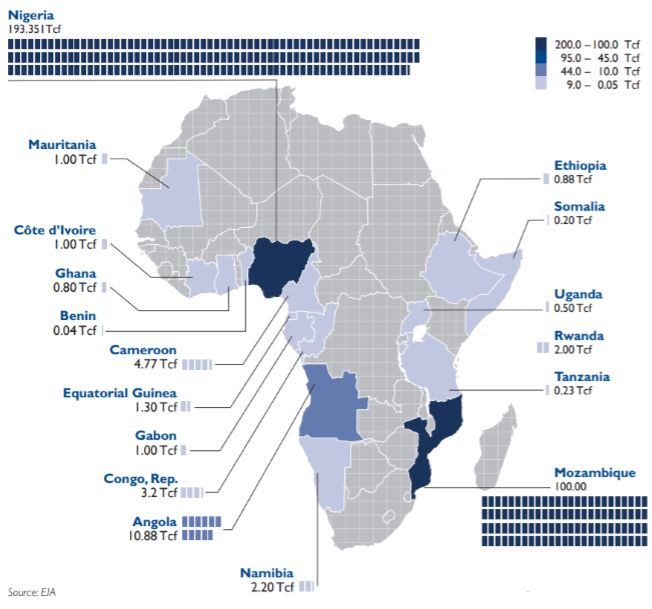

The continent is home to 7% of global reserves and Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to have some 400 GW of gas-generated power potential. Gas resources have been identified in fourteen countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, with Nigeria accounting for 81% of proven reserves and several undeveloped fields in Mozambique and Tanzania accounting for 62% of total contingent resources. Despite these notable gas reserves, only 11 countries have the necessary gas-fired generation capacity installed, and although natural gas supplies nearly one-quarter of all power plants by fuel type, they are mostly located in coastal areas of countries with large proven reserves 5.

PROVEN GAS RESERVES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Almost all the Sub-Saharan African countries could potentially use natural gas for power generation, either by using domestic gas where they have significant gas reserves, by importing gas by pipeline or LNG import terminals, where appropriate, or by interconnection with neighbouring countries.

However, gas consumption in the region is largely supplied by domestic production from within each country, LNG exports are sent outside the region (Angola and Equatorial Guinea largely exist to export LNG and only Nigeria has a relatively well-developed market which both consumes and also exports by both LNG and pipeline).

Furthermore, there are no LNG imports within the region (although FLNG is a potential alternative) and pipeline trade within the region is limited.

If it's accepted that gas has a role to play, not least as an alternative fuel to the traditional fossil fuel, then it will be necessary to not only create the demand for gas in the generation mix but also the appropriate frameworks to support its usage and the infrastructure to deliver it. If this can be achieved then natural gas could not only serve as a fuel for generation but also promote economic growth in key areas such as petrochemicals, refining and manufacturing.

Furthermore, with average development times of approximately two to three years, gas-fired power plants can fill critical electricity gaps much more quickly than large-scale hydro, coal-fired or nuclear plants. In this context, LNG-to-power projects could provide the bridge for developing domestic production of electricity and for the construction of key gas and electricity infrastructure. To date however, they have been slower to be realised than might have been expected.

PROVEN GAS RESERVES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Image source: Power Africa Gas Roadmap to 2030, EIA

WHAT IS CONSTRAINING NATURAL GAS?

Promoting gas generation is not new—the 2016 Power Africa Roadmap outlined plans for the public and private sector partners to work together to add 30,000 MW of new electricity generation capacity and 60 million new connections by 2030. The question therefore is why African countries, lacking investments and infrastructure, have yet to take full advantage of their natural-gas reserves?

While the flexibility of gas for electricity generation makes it an attractive option, the associated infrastructure required to transport and distribute it can significantly restrict its use, potentially limiting it to locations where both demand and infrastructure is well established.

Although the use of natural gas for power generation and other uses could support and encourage infrastructure development and regional integration, there are significant challenges to its development, including the availability of the gas (in terms of both source and delivery point), the relatively small size of the current markets and large distances between markets, the financial position of the off-takers, the lack of adequate downstream infrastructure and the relative size of the markets into which gas might be delivered and the markets ability to take it.

More generally, a challenging operating environment, coupled with a lack of transparency in the resources sector, regulatory uncertainty and policy instability, and a continuing infrastructure deficit, have all deterred investment.

Overcoming these various challenges and addressing the need for environmental and market reforms will be critical to the development of Sub-Saharan African gas-to power markets.

WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT IT?

There are any number of risks which will need to be addressed in order to create a suitable environment for the development of African gas resources—political, economic, legal and operational risks, which will have varying prevalence across the Sub-Saharan region but which will need to be identified and mitigated by the appropriate actions. These include:

- Participation of the state (as guarantor or gas aggregator). State participation brings with it political and economic risks, including the risk of expropriation, the risk that the government may enact fiscal measures that are not favourable to the project, and the risk that the government may enact regulations that are burdensome or refuse to grant requisite licences or approvals

- Sovereign ratings, currency volatility and foreign currency reserves. A sovereign may fail to meet debt repayments resulting in a lower credit rating and increased the risk to lenders. Additionally, hard currency loans can create a currency risk if revenues are denominated in local currency

- Commodity and currency risks. LNG procurement takes place in a commoditized global market, which exposes the project company to the significant risk of price volatility. Furthermore, the procurement of LNG faces currency risks, because LNG market price dynamics are driven by competition for LNG cargoes denominated in U.S. dollars

The challenge is how to use the various measures available to mitigate these risks, including:

- Contractual framework structuring which protects the project company, as far as possible from commodity and currency risks, risks associated with state participation, sovereign risks and risks associated with the project's social impact, with particular focus on the treatment of unforeseeable events or conduct, changes in law, force majeure and grid and gas system events

- Tariff structures which are cost effective and manage foreign exchange risk with costs passes through under the Power Purchase Agreement

- State support, both financial and political

- A robust financial framework, suitable for and appropriate to the project structure (whether integrated, incorporating upstream gas extraction, midstream gas transport and downstream gas delivery/regasification and power generation components, non-integrated, incorporating only some of the functions or a hybrid approach)

- Fuel management techniques, which reduce fuel supply risk, allow for effective storage management and despatch and back up and which allocate liability appropriately

CONCLUSION

If the African Union is to achieve its "Agenda 2063" initiative and transform itself socio-economically over the next 50 years, with the necessary infrastructure in place to support accelerated integration and growth, technological transformation, trade and development, including high-speed railway networks, a well-developed ICT and a digital economy, whist still acting on climate change and ensuring sustainable development, then a stable, reliable, efficient and decarbonized energy system will be needed.

Although environmental and market reforms are critical to the development of Sub-Saharan African gas-to power markets, the successful implementation of path-finder projects will provide models for success. These will be possible where there is a demand for energy, a competitively priced project, supported by secure long-term gas supply and appropriate risk allocation.

Structuring challenges can be addressed at the project level, which can address specific requirements. This flexibility, combined with the key drivers for gasto-power, should mean that gas-to-power projects will continue to play an important role in the generation mix.

The participation of a motivated state entity, supported by multilateral and private institutions in arranging project debt, with the project equity requirements fully funded by the experienced partners will help deliver successful individual projects but wider systemic reforms in creating the appropriate regulatory frameworks and addressing the currently fragmented, project-focused approach that does not consider whole power system dynamics, including bottlenecks in transmission and distribution will still need to be addressed if gas-to-power projects are to successfully deliver their wider range of benefits 6.

Footnotes

1. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Forum, Issue 117, January 2019.

2. International Renewable Energy Association (IRENA) Scaling up renewable energy deployment in Africa Impact of IRENA's engagement, January 2019.

3. Africa50, "Natural gas will make Africa greener", 30 September 2019.

4. Oxford Energy Insight 44, Opportunities for Gas in SubSaharan Africa, January 2019.

5. Algeria, Libya, Egypt and Nigeria.

6. Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) Insight Briefing, Creating a Profitable Balance –Capturing the $110 billion Africa Power Sector Opportunity with Planning, October 2019.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.