- within Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Pharmaceuticals & BioTech and Law Firm industries

- within Criminal Law, Privacy, Government and Public Sector topic(s)

BACKGROUND

Despite the fact, the Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988 came into force on 19.05.1988 (hereinafter referred as "1988 Act") in India, even at that time the concept of benami transaction was not alien in India. There are plenty of judgments wherein the Hon'ble Supreme Court and various High Courts of India have dealt with the concept of benami transaction, and benami transactions have been an integral part of Indian psyche even prior to the advent of 1988 Act.

The Hon'ble Supreme Court in the year 1980 while dealing with the case of Thakur Bhim Singh (Dead) by Lrs and Anr. Vs. Thakur Kan Singh, (1980) 3 SCC 72, had elaborated the concept of "Benami Transaction" and included primarily 2 types of transactions broadly under its purview. Firstly, when a person buys a property with his own money in the name of another person without any intention to benefit such other person and secondly, when a person who is owner of the property executes a conveyance in favour of another without the intention of transferring the title to the property. The relevant extract from the judgment reads as under:

"Two kinds of benami transactions are generally recognized in India.

Where a person buys a property with his own money but in the name of another person without any intention to benefit such other person, the transaction is called benami. In that case, the transferee holds the property for the benefit of the person who has contributed the purchase money, and he is the real owner.

The second case which is loosely termed as a benami transaction is a case where a person who is the owner of the property executes a conveyance in favour of another without the intention of transferring the title to the property thereunder. In this case, the transferor continues to be the real owner.

The difference between the two kinds of benami transactions referred to above lies in the fact that whereas in the former case, there is an operative transfer from the transferor to the transferee though the transferee holds the property for the benefit of the person who has contributed the purchase money, in the latter case, there is no operative transfer at all and the title rests with the transferor notwithstanding the execution of the conveyance. One common feature, however, in both these cases is that the real title is divorced from the ostensible title and they are vested in different persons."

Furthermore, in the above case the Supreme Court has also laid down the parameters for determining, whether a transaction is Benami or not, as under:

"The principle governing the determination of the question whether a transfer is a benami transaction or not may be summed up thus:

(1) The burden of showing that a transfer is a benami transaction lies on the person who asserts that it is such a transaction;

(2) if it is proved that the purchase money came from a person other than the person in whose favour the property is transferred, the purchase is prima facie assumed to be for the benefit of the person who supplied the purchase money, unless there is evidence to the contrary;

(3) the true character of the transaction is governed by the intention of the person who has contributed the purchase money, and

(4) the question as to what his intention was has to be decided on the basis of the surrounding circumstances, the relationship of the parties, the motives governing their action in bringing about the transaction and their subsequent conduct etc."

(Emphasis supplied)

Before coming of the 1988 Act, benami transactions were not illegal in India, and there was no bar or punishment under any law for entering into any benami transaction and the said properties which were the subject matter of the benami transaction were also not liable for confiscation by the government. However, the only thing which was not permitted under the law was recovery of the benami property by the real owner from the benamidar (in whose name the property was held), if the benami transaction was entered to evade a statute or to commit a fraud and the parties succeeded in such evasion or fraud. The Supreme Court in Smt. Surasaibalini Debi vs. Phanindra Mohan Majumdar, AIR1965SC1364, relied upon the decision of the Privy Council in the case of Petherpermal Chetty v. Muniandi Servai [1908] L.R. 35 IndAp 98 and elaborated the aforesaid concept of recovery of property by the real owner as under:

"No doubt, for the purpose of deciding whether property could be recovered by the assertion of a real title there is a clear distinction between cases where only an attempt to evade a statute or to commit a fraud has taken place and cases where the evasion or the fraud has succeeded and the impermissible object has been achieved. The leading decision upon this point is that of the Privy Council in Petherpermal Chetty v. Muniandi Servai [1908] L.R. 35 IndAp 98 where Lord Atkinson dealing with the effect of benami conveyances which are motivated by the design to achieve an illegal or fraudulent purpose, quoted from Mayne's Hindu Law (7th ed. p. 595, para 466) the following as correctly setting out the law:

"Where a transaction is once made out to be a mere benami it is evident that the benamidar absolutely disappears from the title. His name is simply an alias for that of the person beneficially interested. The fact that A has assumed the name of B in order to cheat X can be no reason whatever why a Court should assist or permit B to cheat A. But if A requires the help of the Court to get the estate back into his own possession, or to get the title into his own name, it may be very material to consider whether A has actually cheated X or not. If he has done so by means of his alias, then it has ceased to be a mere mask, and has become a reality. It may be very proper for a Court to say that it will not allow him to resume the individuality which he has once cast off in order to defraud others. If, however, he has not defrauded any one, there can be no reasons why the Court should punish his intention by giving his estate away to B, whose roguery is even more complicated than his own ...... For instance, persons have been allowed to recover property which they had assigned away .... where they had intended to defraud creditors, who, in fact, were never injured ...... But where the fraudulent or illegal purpose has actually been effected by means of the colourable grant, then the maxim applies, 'In pari delicto potior est conditio possidentis'. The Court will help neither party. 'Let the estate liewhere it falls'."

ENACTMENT OF THE BENAMI TRANSACTIONS (PROHIBITION) ACT, 1988

As, there was no law to curb the flourishing benami transactions in India and punish the offenders, the 1988 Act was enacted with an aim to prohibit the benami transactions. The 1988 Act defined benami transactions as a transaction in which property is transferred to one person for a consideration paid or provided by another person, prohibited them and provided punishment for entering into any benami transaction with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years or with fine or with both. The 1988 Act further prohibited recovery of the property held benami from benamidar by the real owner and properties held benami were also liable for confiscation. However, during the process of formulating the rules for implementing certain provisions of the 1988 Act, it was found that owing to infirmities in the legislation it would not be possible to formulate the rules without bringing the comprehensive legislation and repealing the existing 1988 Act. Due to the infirmities in the 1988 Act, relevant rules for implementing the certain provisions of the 1988 Act couldn't see the light of the day. The 1988 Act further didn't provide any mechanism or process of confiscation/acquisition of the benami property and hence, no such effective action for confiscation of benami property could be taken.

On perusal of the 28th report of the Standing Committee on Finance, dated April 2016, on the Benami Transactions Prohibition (Amendment) Bill, 2015, it can be seen that the reason behind amending the 1988 Act instead of repealing the said Act, was to include all the benami transactions under its ambit on which no action was taken under the 1988 Act, so that consequential action could follow. The Ministry of Law was of the opinion that in case, 1988 Act gets repealed by new act then no action would be possible on any such transaction which occurred between 1988 and the date of repealing the 1988 Act, as the benami transactions during the intervening period of twenty six years, would have in fact resulted in immunity since no action could be initiated in the absence of a specific provision in the Repeals and Savings clause. It was therefore suggested by the Ministry of Law, that it would be advisable to comprehensively amend the existing Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988, so that the offences committed during the last twenty six years are also covered.

ADVENT OF THE BENAMI TRANSACTIONS (PROHIBITION) AMENDMENT ACT, 2016

The Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Amendment Act, 2016 which is also be called as Prohibition of Benami Property Transactions Act, 1988 (hereinafter also referred as "2016 Act") finally came into force with effect from 1st November 2016.

The 1988 Act has been substantially amended by the 2016 Act, and various provisions and authorities have been established to curb benami transactions and confiscate benami Properties. Under the 2016 Act, the scope of benami transaction has been widened, and the punishment and penalties have been made more stringent.

CONCEPT OF BENAMI PROPERTY AND BENAMI TRANSACTION UNDER THE 2016 ACT

Under the 2016 Act, the term "Benami Property" under section 1(8) has been defined as under:

- A Benami Property means any property

which is the

- subject matter of a benami transaction

and

- also includes the proceeds from such property.

From the above definition, it is clear that even the proceeds received from a property which is part of a Benami Transaction, will be covered under the definition of Benami Property. The definition of property under 2016 Act include assets of any kind, whether movable or immovable, tangible or intangible, corporeal or incorporeal.

Under Section 1 (9) of the 2016 Act, the term "Benami Transaction" has been defined as under:

A Benami Transaction means,-

- a transaction or an

arrangement-

- where a property

- is transferred to, or is held by, a

person,

and - the consideration for such property has been provided, or paid by, another person;

- is transferred to, or is held by, a

person,

- and

- the property is held for the

immediate or future benefit, direct or indirect, of the person who

has provided the consideration, except when the property is held

by-

- a Karta or a member of a Hindu undivided family..........;

- a person standing in a fiduciary capacity for the benefit of another person towards whom he stands in such capacity.........;

- any person being an individual in the name of his spouse or child ............;

- any person in the name of his brother or sister or lineal ascendant or descendant........; or

- a transaction or an arrangement in respect of a property carried out or made in a fictitious name; or

- a transaction or an arrangement in respect of a property where the owner of the property is not aware of, or, denies knowledge of, such ownership; or

- a transaction or an arrangement in respect of a property where the person providing the consideration is not traceable or is fictitious.

- where a property

From a plain reading of the above Section, it has been mandated that following transactions shall fall under the scope of Benami Transaction:

- Where the property is held by or transferred to another person, andthe property is held by that another person, for the immediate or future benefit of the person who has provided the consideration for such property;

- Where a transaction has been made under a fictitious name;

- Where the owner is not aware or denies knowledge of the ownership of the property; and

- The person providing the consideration is not traceable.

AUTHORITIES ESTABLISHED UNDER THE 2016 ACT

The 2016 Act provides for setting 4 major Authorities, namely:

- The Initiating Officer

- The Approving Authority

- The Administrator

- The Adjudicating Authority

For the purpose of the 2016 Act, the above authorities have been vested with the same powers as those of the Civil Courts under Civil Procedure Code, 1908

PROCESS OF ATTACHMENT OF BENAMI PROPERTY

- Under Section 24 of the 2016 Act, the

Initiating Officer, if has reason to believe that any person is

benamidar, will issue notice to:

- Benamidar

and - Beneficial owner (if identity known).

- Benamidar

- The Initiating Officer with the

approval of Approving Authority can attach the property for a

period not exceeding 90 days, if in his opinion, the person to whom

notice has been issued may alienate the property during notice

period.

The Initiating Officer shall after making inquiries and considering evidence and all other relevant material, with the approval of Approving Authority and within a period of 90 days from the date of issuance of notice: - If there is a provisional

attachment:

- Pass an order continuing the provisional attachment of the property till the adjudication order by the Adjudicating Authority; or

- Revoke the provisional attachment order.

- If there is no provisional

attachment:

- Pass an order for attaching the property till the adjudication order by the Adjudicating Authority; or

- Decide not to attach the

property.

If there is any order for attachment of the property or continuation of the provisional attachment, the Initiating Officer shall draw up a statement of the case and refer it to Adjudicating Authority within 15 days from the date of such attachment.

ADJUDICATION OF BENAMI PROPERTY

- After the reference is made to the

Adjudicating Authority by the Initiating Officer, the Adjudicating

Authority under Section 26 of the 2016 Act, within 30 days of the

reference, shall issue notice to:

- Benamidar;

- Beneficial owner (if identity known);

- Any interested party( including banking company);

- Any person who has made claim in the respect of the benami property; and

- All the joint owners if the property is held jointly (if identity known).

- To furnish all documents and evidence

in their support.

- A period of at least 30 days shall be given to the person, to whom the notice has been issued.

- After considering the reply, evidence

and all other relevant material, and granting an opportunity of

being heard to the affected parties and the Initiating Officer, the

Adjudicating Authority should pass an order holding property:

- As not to be benami and revoking the attachment order; or

- As to be benami and confirming the attachment order.

- Adjudicating Authority has to pass an order before the expiry of one year from the end of the month in which the Initiating Officer has made the reference.

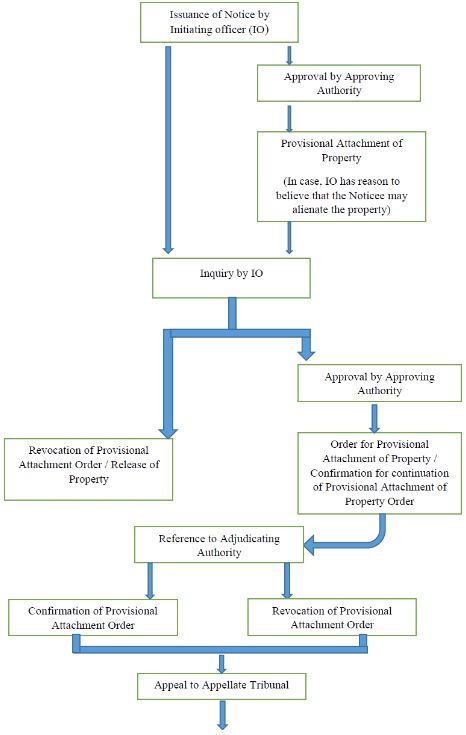

SEQUENCE CHART BRIEFLY EXPLAINING THE PROCESS OF ATTACHMENT OF BENAMI PROPERTY AND ITS ADJUDICATION

CONFISCATION OF BENAMI PROPERTY

- If the Adjudicating Authority has

held any property as benami property, the Adjudicating Authority

under Section 27 of the 2016 Act, shall after giving an opportunity

of hearing to the concerned person, pass an order to confiscate the

attached property.

- If an appeal has been preferred against the order of attachment passed by Adjudicating Authority, the property shall be confiscated after the order of the Appellate Tribunal.

- If any property is held or acquired by any person from the benamidar for adequate consideration prior to the issuance of the Notice by Initiating Officer, that property won't get confiscated.

- Any right of any third person created in such property with a view to defeat the purposes of this Act shall be null and void.

- Pursuant to the order of confiscation, all the rights and title in such property shall vest absolutely with the central government free of all encumbrance and no compensation shall be payable.

- The Administrator will administer the confiscated property.

APPEALS

- Any person aggrieved by the order of the Adjudicating Authority of holding the property as benami or not, can file an appeal to the Appellate Tribunal within 45 days from the date of the order. An appeal against the order of the Appellate Tribunal may be preferred in the High Court within 60 days.

PROHIBITION OF & PENALTY FOR BENAMI TRANSACTIONS

- Any person who had entered into any benami transaction prior to the commencement of the 2016 Act shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years or with fine or with both.

- Under Section 53 of the 2016 Act, whosoever enters into any benami transaction on and after the date of commencement of the 2016 Act i.e. 11th November 2016, and any other person who abets or induces any person to enter into the benami transaction, shall be guilty of the offence of benami transaction and shall be punishable with rigorous imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than one year, but which may extend to seven years and shall also be liable to fine which may extend to 25% of the fair market value of the property.

COMMENTS

From comparison of the 1988 Act with the 2016 Act, it becomes clear that 1988 Act didn't have any mechanism or process of confiscation/ acquisition of the benami property and therefore, no benami property could be acquired by the government. On the other hand, the 2016 Act is a comprehensive law which not only provides for the mechanism and process for attachment and confiscation of the benami property, but has also enaected the administrative structure for proper implementation of such provisions. The 2016 Act has not only widened the ambit of benami Transaction, but the same also mandates for more stringent punishment. By the 2016 Act, the Government of India has made its intentions abundantly clear that the benami transactions occurred during the intervening period of 1988 to 2016 are not going to be spared.

However, in order to protect the bonafide purchaser of the benami property, from the perusal of the Section 27 clause (3) and (4) of the 2016 Act, it can be observed that the 2016 Act has excluded the benami properties which has been purchased by the bonafide purchaser for adequate consideration, prior to the issuance of notice by the Initiating Officer, from the scope of confiscation under the 2016 Act.

It appears that inadvertently, the Parliament while amending the 1988 Act did not make any amendment in sub clause 3 of Section 1 of 1988 Act, which deals with the different effective date of sections 3, 5 and 8 of the 1988 Act from the rest of the sections of 1988 Act. As, no amendment has been made in sub clause 3 of Section 1 of 1988 Act under the 2016 Act, the same reads as under:

"The provisions of sections 3, 5 and 8 shall come into force at once, and the remaining provisions of this Act shall be deemed to have come into force on the 19th day of May, 1988".

Due to the existence of the aforesaid provision in the 2016 Act, it is likely that unnecessary confusion will prevail on the date of application of the sections of 2016 Act, thereby causing unwarranted litigation and ridiculous interpretations as to the applicability of the 2016 Act.

There is no doubt that 2016 Act has been enacted to bolster the efforts of the Government to curb the parallel economy and eradicate the black money, and this enactment has some teeth to deal with the menace of benami transactions.

By

Vijay Pal Dalmia, Advocate

Supreme Court of India & Delhi High Court

Mobile: +919810081079

Email: vpdalmia@vaishlaw.com

AND

Rajat Jain, Advocate

Mobile: +91 9953887311

Email: rajatjain@vaishlaw.com

© 2017, Vaish Associates Advocates,

All rights reserved

Advocates, 1st & 11th Floors, Mohan Dev Building 13, Tolstoy

Marg New Delhi-110001 (India).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist professional advice should be sought about your specific circumstances. The views expressed in this article are solely of the authors of this article.