- within Corporate/Commercial Law and Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

Indian jurisprudence has long been dedicated to maintaining a balance between individual rights, leading to the development of a multitude of laws. Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 and Article 226 of the Constitution of India, 1949, are pivotal legal provisions conferring authority upon the High Courts to ensure justice and enforce orders. While both serve a similar objective, they exhibit distinct applications. This article thoroughly explores the nuanced scenarios where they should be used separately rather than interchangeably. It provides an exhaustive analysis of their scope, constraints, and an informed choice of remedy, emphasizing the need for judicious exercise of these powers within the Indian legal framework.

INTRODUCTION

Within Indian jurisprudence, the primary objective has perennially revolved around striking a delicate equilibrium between the rights of individuals, necessitating the creation of a plethora of laws over time. However, it remains impractical to encompass every conceivable situation within the ambit of these laws. Consequently, various legal provisions have been incorporated into these statutes, vesting the judiciary with the authority to address matters that, while not explicitly delineated in the statutes, demand resolution in the relentless pursuit of justice. Two such provisions that contribute significantly to this endeavour are section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 ("CrPC"), and Article 226 of the Constitution of India, 1949 ("Constitution").

Section 482 of the CrPC confers inherent power upon the High Court, whereas Article 226 of the Constitution outlines the High Court's authority to issue writs. Both provisions are geared towards ensuring justice for individuals and facilitating the enforcement of their own orders.

It is not uncommon for these provisions to be employed interchangeably, a practice that, as we will explore in this article, appears to be fundamentally incorrect. While both provisions ostensibly share a common objective, their application diverges significantly. This divergence prompts us to question which remedy one should opt for in various circumstances. This article seeks to shed comprehensive light on the distinct situations and contexts in which these remedies should be employed separately, rather than interchangeably.

SECTION 482 OF THE CrPC- AN ANALYSIS

Section 482 of the CrPC provides that: -

"Saving of inherent powers of High Court- Nothing in this Code shall be deemed to limit or affect the inherent powers of the High Court to make such orders as may be necessary to give effect to any order under this Code, or to prevent abuse of the process of any Court or otherwise to secure the ends of justice."

Section 482 of the CrPC is based on the maxim "quando lex aliquid alicui concedit, concedere videtur ed it sine quo res ipsae esse non potest" which means that: -

"When the law gives anything to anyone, it also gives all those things without which the thing itself would be unavailable, implying that if the court has the power to order something, it equally possesses the power to make any other order which is mandatory in enforcing or implementing such orders effectively."

As can be observed from the plain reading of the provision and rulings of the courts in various cases, High Courts can exercise section 482 of the CrPC in the following conditions1: -

(i) In order to give effect to an order under the CrPC,

(ii) To prevent abuse of the process of the court and

(iii) To otherwise secure the ends of justice.

Further, in the case of Dr. Monica Kumar & Anr. v. State of Uttar Pradesh2, it was held that section 482 of the CrPC is to be exercised ex debito justitiae (as a matter of right) in a manner to ensure real and substantial justice. Furthermore, the procedure of exercising the inherent powers is regulated through rules framed by the High Court.

Notably, the application under section 482 of the CrPC can be exercised only when no other remedy is available to the litigant.3 In Madhu Limaye v. State of Maharashtra,4 the Hon'ble Supreme Court observed that the High Court needs to exercise the inherent based on the following principles:-

(a) The power is not to be resorted to if there is a specific provision in the Code for the redress of the grievance of the aggrieved party.

(b) It should be exercised very sparingly to prevent abuse of the process of any court or otherwise to secure the ends of justice.

(c) It should not be exercised as against the express bar of the law engrafted in any other provision of the Code.

Additionally, even though section 482 of the CrPC does not explicitly enumerate its applicability, an examination of High Court practices reveals that it has been invoked in various contexts, including 5: -

- Quashing of FIR.

- Quashing of complaint.

- Quashing of Charge-sheet.

- Passing directions to register the case.

- Passing direction for reinvestigation.

- Quashing of any order passed by the courts below.

Furthermore, in the case of BS Joshi v. State of Maharastra6, the Supreme Court, while permitting the settlement in a section 498-A Indian Penal Code case, observed that section 482 of the CrPC can be employed to compound even non-compoundable offences to secure the ends of justice.7 However, it is essential to note that such application under section 482 of the CrPC is not permissible in grave offences such as murder, rape, dacoity, etc., or offences governed by specific laws, such as acts of corruption by public servants.8

Considering these points, it becomes evident that the inherent powers vested in the High Courts under section 482 of the CrPC are broad and extensive. Consequently, it is imperative that these powers are exercised sparingly, cautiously, and judiciously.

Therefore, it has been observed by the apex court in various cases that applications filed under section 482 of the CrPC need to be examined earnestly by the High Courts, considering its broad nature.9

The apex court has consistently emphasized that applications filed under section 482 of the CrPC must be examined earnestly by the High Courts, given the breadth of their authority. A significant cautionary note is that when exercising this inherent power, High Courts should refrain from functioning as appellate or revisional courts. The Criminal Procedure Code explicitly provides for appeal and revision mechanisms. Additionally, in the case of Hari Singh Mann v. Harbhajan Singh10, the Hon'ble Supreme Court held that applications under section 482 of the CrPC for the review of High Court judgments, whether in appellate, revisional, or original jurisdiction, should not be entertained.

Furthermore, High Courts are restricted from delving into factual determinations when entertaining applications under section 482 of the CrPC. The case of Dineshbhai Chandubhai Patel v State of Gujarat11 underscores that High Courts cannot assume the role of an investigative agency when examining the factual contents of an FIR in response to an application under section 482 of the CrPC. Moreover, in cases such as the State of Bihar and another v. K.J.D. Singh12 and Janta Dal v. H.S. Chowdhary13, it has been established that trials or investigations should only be stayed or quashed under section 482 of the CrPC in exceptional circumstances.14

In the case of State of Rajasthan v. Ravi Shankar Srivastava,15, it was further affirmed that under section 482 of the CrPC, courts should only pass orders necessary for the disposal of the case, without adding anything beyond this requirement.

Finally, it is essential to note that orders issued under section 482 of the CrPC are not subject to appeal through statutory appeal provisions. An aggrieved party must approach the Supreme Court under Article 136 of the Constitution to challenge such an order.

ARTICLE 226 OF THE CONSTITUTION- AN ANALYSIS

Article 226 of the Constitution empowers the High Courts to issue writs against any person or authority, including the government, for the enforcement of fundamental rights and other orders against government authorities or individuals. The Hon'ble Supreme Court, through various cases, has laid down that:-16

(i) The power under Article 226 of the Constitution to issue writs is not restricted solely to the enforcement of fundamental rights; it can also be employed for various other purposes.

(ii) If an effective alternate remedy is available to the aggrieved person, then the petition will not be maintainable.

(iii) However, there are a few Exceptions to the rule of alternate remedy, as follows:-

(a) if the petition is filed in concern of violation of any fundamental rights.

(b) if there has been a violation of the principles of natural justice.

(c) if the orders or proceedings have been conducted are wholly without jurisdiction.

(d) the vires of a legislation is challenged.

(iv) In situations involving contested factual issues, the High Court may opt not to exercise its jurisdiction in a writ petition.

Similar to section 482 of the CrPC, Article 226 of the Constitution also confers upon the High Courts a broad and extensive power. Interestingly, the corresponding Article in the Constitution for the Supreme Court, Article 32, has a narrower scope than Article 226. Article 32 is not limited to the enforcement of fundamental rights but extends to the enforcement of any legal rights as well. 17

However, like section 482 of the CrPC, there are certain cautions associated with the power vested under Article 226. For instance, in the case of Veerappa Pillai v. Raman and Raman Limited,18 it was established that while the jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution is broad, it does not permit the High Court to function as a Court of Appeal. Similarly, in the case of Chandigarh Administration v. Manpreet Singh (1991),19 it was clarified that the jurisdiction of the High Courts under Article 226 is purely supervisory in nature and not appellate.

CHOICE OF REMEDY

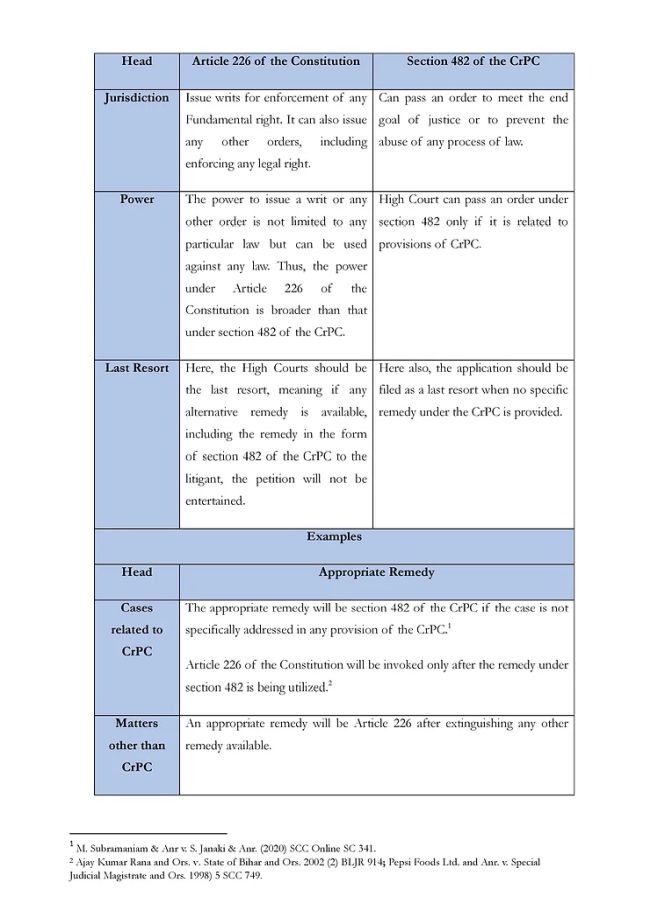

The preceding discussion has provided a comprehensive overview of the jurisdiction of both these provisions. Now, the decision regarding which remedy to pursue, whether through Article 226 of the Constitution or section 482 of the CrPC, in varying situations and circumstances, can be better comprehended through the following table:-

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the selection between Article 226 and section 482 of the CrPC should be a deliberate choice, taking into consideration the nature of the legal issue at hand. When dealing with matters beyond the scope of the CrPC, Article 226 of the Constitution emerges as the appropriate remedy, but only after exhausting other available options. Section 482 of the CrPC should be invoked when addressing issues directly related to the CrPC. In both cases, the exercise of these powers by High Courts must be judicious, sparing, and guided by principles of justice.

To sum up, the decision between Article 226 of the Constitution and section 482 of the CrPC is not a matter of preference but rather one of legal appropriateness. A thorough understanding of the intricacies of these provisions and the specific scenarios in which they are applicable is essential to ensure that the correct remedy is pursued, thereby facilitating efficient and effective justice delivery within the Indian legal system.

Footnotes

1. Narinder Singh v. State of Punjab (2014) 6 SCC 466; State of Karnataka v. Muniswamy AIR 1977 SC 1489.

2. Dr. Monica Kumar & Anr. v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2008) 8 SCC 781.

3. R.P. Kapoor v. the State of Punjab 1960 SCR (3) 311.

4. Amit Kapoor v. Ramesh Chander (2012) 9 SCC 460.

5. Amit Kapoor v. Ramesh Chander (2012) 9 SCC 460; Sakiri Vasu v. State of U.P (2008) 2 SCC 409.

6. BS Joshi v. State of Maharastra (2003) 4 SCC 675.

7. Gian Singh v. State of Punjab (2012) 10 SCC 303; Sushil Kumar Sharma v. Union of India (2005) 6 SCC 281; B S Joshi v. State of Haryana 2003 (4) SCC 675; Geeta Mehrotra v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2012) 10 SCC 741.

8. Parbatbhai Ahir v. State of Gujarat (2017) 9 SCC 641.

9. Sakiri Vasu v. State of U.P. (2008) 2 SCC 409; Arun Shankar Shukla v. State of U.P. (1999) 6 SCC 146.

10. Hari Singh Mann v. Harbhajan Singh (2001) 6 SCC 169.

11. Dineshbhai Chandubhai Patel v. State of Gujarat (2018) 3 SCC 104.

12. State of Bihar and another v. K.J.D. Singh 1994 SCC (Cri) 63.

13. Janta Dal v. H.S. Chowdhary (1992) 4 SCC 305.

14. Central Bureau of Investigation v. Aryan Singh, 2023 SCC OnLine SC 379.

15. State of Rajasthan v. Ravi Shankar Srivastava (2011) 10 SCC 632.

16. Radha Krishan Industries v. State of Himachal Pradesh (2021) 6 SCC 771; Whirlpool Corporation v. Registrar of Trademarks (1998) 8 SCC 1; Harbanslal Sahnia v. Indian Oil Corpn. Ltd. (2003) 2 SCC 107.

17. Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. the Union of India (1984) 3 SCC 161; Common Cause v. the Union of India (2018) SCC Online 945.

18. Veerappa Pillai v. Raman and Raman Limited 1952 SC 583.

19. Chandigarh Administration v. Manpreet Singh 1991 SCR Supl. (2) 322.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.