- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in Asia

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in Asia

- in Asia

- within Intellectual Property, Litigation, Mediation & Arbitration and Privacy topic(s)

- with Inhouse Counsel

- with readers working within the Pharmaceuticals & BioTech and Law Firm industries

1 Legal framework

1.1 What legislative and regulatory provisions govern copyright in your jurisdiction?

The governing statue in India is the Copyright Act, 1957, together with the Copyright Rules, 2013. In 1999, the government passed the International Copyright Order, which makes the act applicable to all works first made or published in a Berne Convention or Universal Copyright Convention country, in like manner, as if they were first made or published in India. The term of protection, however, is limited to that enjoyed in the country of origin.

1.2 Is there common law protection for copyright in your jurisdiction?

Registration is not necessary to enforce copyright in India, as long as the work is published/registered in a country that is a signatory to the Berne Convention or the Universal Copyright Convention. A suit for copyright infringement does not require formal registration of copyright with the Copyright Office and common law remedies can be invoked.

1.3 Do any special regimes apply to specific types of works or subject matter (eg, software; data and databases; digital works; indigenous works)?

There are no specific regimes applicable to any particular category of work insofar as copyright protection and registration are concerned.

1.4 Which bilateral or multilateral instruments or treaties with effect in your jurisdiction (if any) have relevance for copyright protection?

India is a member of the following international treaties and conventions:

- the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, 1886;

- the Universal Copyright Convention, 1952;

- the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights 1995;

- the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Copyright Treaty, 1996; and

- the WIPO Performers and Phonogram Treaty, 1996.

1.5 Which bodies are responsible for implementing and enforcing the copyright regime in your jurisdiction? What is their general approach in doing so?

The Copyright Office and the civil and criminal courts in India are responsible for implementing and enforcing the copyright regime in India. Their general approach is pro-rights holder, provided that the rights holder can fulfil the standard required to establish copyright in the work.

2 Copyrightabilty

2.1 What types of works qualify for copyright protection in your jurisdiction?

As per the Copyright Act, copyright subsists in the following classes of works:

- original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works;

- cinematographic films; and

- sound recordings.

The definition of 'literary work' includes computer programs, tables and compilations, including computer databases.

2.2 What are the requirements for copyrightability?

An idea per se has no copyright. Copyright protection/registration is granted only to works which are expressed in a tangible form. For all works in which copyright is sought, the test of originality must be fulfilled. An 'original work' is one which:

- originates from the author; and

- is not a mere copy/imitation of another person's work.

2.3 What types of works are ineligible for copyright protection in your jurisdiction?

A mere idea cannot be protected; only the expression of such idea in a tangible form may be protected. Any work which lacks originality will be ineligible for copyright protection.

3 Scope of protection

3.1 What legal rights are conferred by copyright in your jurisdiction?

In India, different exclusive rights are vested in the author/owner of copyright based on the type of work protected.

In the case of a literary, dramatic or musical work, which is not a computer program, these rights include the right to:

- reproduce the work;

- issue copies;

- perform the work in public or communicate it to the public;

- make any cinematographic film or sound recording in respect of the work;

- make any translation of the work; or

- make any adaptation of the work.

In the case of a computer program, the rights include the right to:

- do any of the acts specified above; and

- sell or give on commercial rental a copy.

In the case of an artistic work, the rights include the right to:

- reproduce the work;

- communicate the work to the public;

- issue copies of the work to the public;

- include the work in any cinematographic film; and

- make any adaptation of the work.

In the case of a cinematographic film, the rights include the right to:

- make a copy of the film, including a photograph of any image forming part thereof;

- sell or give a copy on commercial rental; and

- communicate the film to the public.

In the case of a sound recording, the rights include the right to:

- make any other sound recording embodying it;

- sell or give the sound recording on commercial rental; or

- communicate the sound recording to the public.

3.2 Are there special rules that limit the scope of protection for works that are useful/utilitarian/functional in your jurisdiction?

Section 52 of the Copyright Act lists several actions which do not amount to infringement of copyright. These include, among other things:

- the reproduction of any work:

-

- by a teacher or a pupil in the course of instruction;

- as part of the question to be answered in an examination; or

- in answers to such questions;

- the performance in an educational institution, if the audience is limited to staff, students, parents and guardians;

- the public playing of a record:

-

- in an enclosed room or hall meant for the common use of residents in any residential premises (not a hotel or commercial establishment) as part of the amenities provided for residents; or

- as part of the activities of a club or similar organisation which is not established or conducted for profit;

- the performance of a literary, dramatic or musical work by an amateur club or society, if the performance is given:

-

- to a non-paying audience; or

- for the benefit of a religious institution;

- the reproduction in a newspaper, magazine or other periodical of an article on current economic, political, social or religious topics, unless the author has expressly reserved the right of such reproduction;

- the storage of a work in any medium by electronic means by a non-commercial public library for preservation, if the library already possesses a non-digital copy of the work;

- the making of not more than three copies of a book (including a pamphlet, sheet of music, map, chart or plan) for the use of a library, if this material is not available for sale in India;

- the making of a three-dimensional object from a two-dimensional artistic work, such as a technical drawing, for the purposes of industrial application of any purely functional part of a useful device;

- the reconstruction of a building or structure in accordance with the architectural drawings or plans by reference to which the building or structure was originally constructed;

- the making of an ephemeral recording and the retention of such recording for archival purposes on the grounds of its exceptional documentary character;

- the performance of a literary, dramatic or musical work or the communication to the public of such work or of a sound recording in the course of any bona fide religious ceremony or an official ceremony held by the central government or the state government or any local authority; or

- the adaptation, reproduction, issue of copies or communication to the public of any work in any accessible format by:

-

- any person to assist persons with a disability in accessing the work; or

- any organisation working for the benefit of persons with disabilities in case the normal format prevents the enjoyment of such works by such persons.

3.3 Are neighbouring rights protected in your jurisdiction? If so, please outline the applicable regime.

Yes, neighbouring rights are protected in India under rights of broadcasting organisations and of performers.

Broadcasting reproduction rights: A 'broadcast' involves the communication to the public by any means of wireless diffusion in the form of signs, sounds or visual images, or by wire.

A broadcasting organisation holds the exclusive right to:

- rebroadcast;

- cause a broadcast to be heard or seen by the public on payment of charges;

- make any sound or visual recording of the broadcast or any reproduction thereof; or

- sell or rent, or offer to sell or rent, such recording.

These rights subsist for 25 years from the beginning of the calendar year following that in which the broadcast is made

Performers' rights: A 'performer' is any person who makes a performance. Among others, these include:

- singers;

- actors;

- acrobats;

- dancers;

- musicians;

- conjurers;

- jugglers; and

- snake charmers.

Performers hold the exclusive right to:

- make a sound or visual recording of their performance;

- reproduce such recordings;

- issue copies of such recordings;

- communicate such recordings to the public; and

- sell or rent, or offer to sell or rent, such recordings.

These rights subsist with the performer for a period of 50 years from the beginning of the calendar year following that in which the performance is made. However, if the performer consents to the incorporation of the performance in a cinematographic film, his or her rights to such performance will expire.

3.4 Are moral rights protected in your jurisdiction? If so, please outline the applicable regime.

Yes, the moral rights of performers are protected in India. A performer can restrain or claim damages in respect of any distortion, mutilation or other modification that would be prejudicial to his or her reputation.

3.5 Are any blanket exceptions to copyright infringement (eg, fair use/dealing) or specific exceptions to copyright infringement (eg, backup copies, interoperability, right of repair) available in your jurisdiction? If so, under what conditions do they apply?

Fair dealing is an exception to copyright infringement and is recognised under the Copyright Act. Fair dealing involves the use of any work which is not a computer program for the purpose of:

- private or personal use, including research;

- criticism or review, whether of that work or of any other work; or

- the reporting of current events and current affairs, including the reporting of a lecture delivered in public.

For computer programs, exceptions to copyright infringement include:

- making copies of a computer program:

-

- in order to utilise the program; or

- purely as a temporary protection against loss, destruction or damage;

- acting in a way which is necessary to obtain information that is essential to ensure the interoperability of an independently created computer program with other programs;

- observing, studying or testing the functioning of the computer program in order to determine the ideas and principles which underline any elements of the program; and

- making copies or adaptations of the program for non-commercial personal use.

Several other exceptions to infringement are provided under the Copyright Act and have been developed by courts of law.

3.6 How are derivative works protected in your jurisdiction? Who is the owner of a derivative work?

The right to make translations and adaptions of any work rests with the author or the first owner. Under the Copyright Act, the term 'adaptation' means:

- in relation to a dramatic work, the conversion of the work into a non-dramatic work;

- in relation to a literary work or an artistic work, the conversion of the work into a dramatic work by way of performance in public or otherwise;

- in relation to a literary or dramatic work, any abridgement of the work or any version of the work in which the story or action is conveyed wholly or mainly by means of pictures in a form that is suitable for reproduction in a book, newspaper, magazine or similar periodical;

- in relation to a musical work, any arrangement or transcription of the work; and

- in relation to any work, any use of such work involving its rearrangement or alteration.

3.7 Can copyrightable works also be protected by other IP rights (eg, trademarks and designs) in your jurisdiction?

Copyright and designs are governed by two different statutes:

- the Copyright Act, 1957; and

- the Designs Act, 2000.

The definition of a 'design' under the Designs Act specifically excludes, among other things, any artistic work as defined in Section 2(c) of the Copyright Act. This differs from design protection, which aims to protect novel designs which are devised to be applied to articles to be manufactured and marketed commercially. Once a design has been registered under the Designs Act, it loses its copyright protection under the Copyright Act. An unregistered design will continue to enjoy copyright protection for up to 50 reproductions by an industrial process. An artistic work which is used or capable of being used in respect of any goods or services may be protected by copyright, as well by a trademark under the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

4 Duration, publication and renewal

4.1 When does copyright protection in a work begin and end in your jurisdiction? Are there any proactive maintenance or other requirements to benefit from a full term of protection?

| Work | Term of protection |

|---|---|

| Published literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works |

The lifetime of the author plus 60 years from the beginning of the year following the death of the author. Where joint authorship is claimed for a work, this 60-year period will commence after the death of the last surviving author. In case of anonymous works, copyright subsists for 60 years from the beginning of the year following the first publication date. However, if the identity of the author is disclosed before the expiry of this period, it will subsist for 60 years from the beginning of the year following the death of the author. |

| Cinematographic films | 60 years from the beginning of the year following the first publication of the film. |

| Sound recordings | 60 years from the beginning of the year following the first publication of the recording. |

| Government works, works of public undertakings and international organisations | 60 years from the beginning of the year following the first publication of such work. |

The Copyright Act does not prescribe any maintenance or other requirements to benefit from a full term of protection.

4.2 What is required for a work to be published in your jurisdiction?

A work is deemed to be published where it is made available to the public. This may be done through the issuance of copies of a work or the communication of a work to the public. A work will not be deemed to have been publicly published/performed if it is performed/published without the authorisation of the copyright owner.

4.3 Can copyright protection be renewed or extended in your jurisdiction? If so, how?

The term of protection is fixed and the Copyright Act does not provide any mechanism to renew or extend copyright protection.

5 Ownership

5.1 Who can qualify as the owner of a copyrighted work in your jurisdiction? Are there any provisions that deem an owner to be a person other than the author?

The 'author' of a work is prima facie considered to be the 'first owner' of the copyright therein. The 'author' has been defined:

- in relation to a literary or dramatic work, as the author of the work;

- in relation to a musical work, as the composer;

- in relation to an artistic work other than a photograph, as the artist;

- in relation to a photograph, as the person taking the photograph;

- in relation to a cinematographic film or sound recording, as the producer; and

- in relation to any literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer generated, as the person who causes the work to be created.

The 'owner' of a copyright may differ from the author:

- in case of the assignment of works; and

- by virtue of a contract of service.

5.2 Is corporate, joint or collective ownership of copyrighted works recognised in your jurisdiction? If so, in what circumstances?

Works of joint authorship are recognised under the Copyright Act as works produced by the collaboration of two or more authors in which the contribution of one author is not distinct from that of the others. Exploitation of the work (including the grant of licences) must be made jointly by all authors. The act does not specifically recognise works of joint ownership per se.

5.3 Can ownership of a copyrighted work be transferred in your jurisdiction? If so, how? Are any copyrights, moral rights, neighbouring or related rights inalienable? If so, how can such rights be dealt with (eg, exclusive licence, waivers)?

Yes, the rights of an owner in an existing work or the rights of a prospective owner in a future work may be transferred by way of assignment, either full or partial. This assignment:

- may be general or subject to limitations; and

- may be provided for the whole term of copyright or any part thereof.

Mode of assignment: An assignment agreement must be:

- executed in writing; and

- duly signed either by the assignor or by his or her authorised representative.

The agreement must specify:

- the work and the rights assigned;

- the duration and territorial extent of the assignment;

- the royalty or other consideration payable; and

- other mutually agreed terms.

Automatic lapse of assignment: An assignee (ie, the party to which the mark is assigned) must exercise the rights assigned to it within one year of the date of assignment of such rights. Failure to do so before the expiry of this period will result in the automatic lapse of the assignment, unless the assignment agreement specifies anything to the contrary.

Details not specified in the assignment agreement: If the assignment agreement does not specify the duration or territorial extent of the assignment, the agreement will be assumed to:

- have effect for five years from the date of such assignment; and

- extend to the whole of India and not beyond its territory

Rights which may not be transferred: Under no circumstances can the moral rights of an author be transferred. The authors of any literary or musical work which has been included in a cinematographic film/sound recording are entitled to receive a royalty for such exploitation of the work. This right is inalienable and restrictions have been imposed on the assignment of such right to any person other than a legal heir or a copyright society. In case of a performance incorporated in a cinematographic film:

- the same inalienable right subsists for the performer; and

- such right may not be transferred to any person other than a legal heir or a performers' rights society.

5.4 Where a work is created by an employee, what are the rules regarding ownership? What measures can an employer take to secure its rights to intellectual property created under an employment relationship?

If a work is created in the course of the author's employment under a contract of service, the employer, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, is regarded as the first owner of copyright vesting in the work. The exceptions are:

- literary, dramatic or artistic works made by the author in the course of his or her employment by the proprietor of a newspaper, magazine or similar periodical; and

- photographs, paintings or portraits, engravings and cinematographic film.

Under a contract of service, there is no requirement to execute a specific assignment agreement with the employee for each work, as the copyright will automatically subsist with the employer.

5.5 Where a work is created by a contractor, what are the rules regarding ownership? What measures can a hiring party take to secure its rights to intellectual property created under a contracting relationship?

Where a work is created in the course of the author's employment under a contract for service, the employee, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, is regarded as the first owner of the copyright vesting in the work.

In such case, the assignment of the ownership of the work so created by the employee is required for the employer to be entitled to the rights comprised in the copyright in question. The Copyright Act provides for the mode of assignment of the copyright in any work.

6 Registration

6.1 Is there a copyright registration system in your jurisdiction? If so, is registration mandatory?

Yes, there is a copyright registration system in India. An application may be filed with the Copyright Office along with the necessary supporting documents and the official fee. Registration of copyright is not mandatory in India; copyright subsists in a work as soon as it comes into existence. No limitation is imposed on the enforcement of rights due to non-registration of copyright with the Copyright Office.

6.2 What are the advantages of registration?

Copyright registration:

- is easy to obtain;

- is cost effective; and

- assists in enforcement actions such as:

-

- trademark opposition/cancellation actions;

- lawsuits;

- search and seizure operations;

- anti-counterfeiting measures; and

- customs notices.

6.3 What legal presumptions, rights and entitlements are conferred by copyright registration?

Registration of copyright does not bestow any new rights or entitlements upon the owner. Registration constitutes prima facie evidence of the owner's rights.

6.4 What are the formal, procedural and substantive requirements for registration?

Procedure: A no-objection/clearance certificate (NOC) is required in respect of an artistic work that is used or capable of being used in respect of goods or services. The NOC is obtained by filing an appropriate request with the Trademarks Registry along with the fee and representations of the artistic work. On receipt of this request, the registry may revert with an official action, containing any deceptively similar/identical marks, which must be responded to accordingly. Of course, the registry may also issue the NOC without raising any objections.

Upon receipt of the NOC, an application will be tendered to the Copyright Office in the prescribed form with the requisite fee and supporting documents. For all other works, an application is filed directly with the Copyright Office. The registrar of copyrights will examine the application. If the application is deficient in certain respects, the registrar may issue an official letter requiring that remedial measures be taken. Alternatively, if the registrar raises no objections, the work will be registered.

The following documents/information is required:

- title and copies of the work;

- details such as the name, nationality and address of the author of the artistic work, who must be a natural person. Where a team of persons created the work in question, the head of the team may be designated as the author; and

- a deed of assignment and NOC, if applicable.

6.5 What fees does the governing body charge for registration? Do these vary depending on the type of work?

Yes, the fee for registration varies depending on the type of work, as follows.

| Registration application | Fees |

|---|---|

| Literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works | INR 500 per work |

| Literary or artistic works which are used or capable of being used in relation to any goods or services | INR 2,000 per work |

| Cinematographic films | INR 5,000 per work |

| Sound recordings | INR 2,000 per work |

6.6 Can copyright registration be refused? If so, on what grounds and what is the impact of refusal?

Yes, a copyright application may be refused if the work is not original. While there are no codified grounds on which a copyright application may be refused, the impact of refusal is the inability to claim or enforce any rights to the work in question.

6.7 If copyright registration is refused, can the applicant appeal? If so, how?

Yes, anyone aggrieved by any final decision or order of the registrar of copyrights may appeal to the high court within three months of the date of the order or decision.

6.8 Can the reviewing body's decision be appealed? If so, how?

Yes, the decision of a single judge of the high court can be appealed before a division bench of the same high court and thereafter, a further appeal can be filed with the Supreme Court.

7 Enforcement and remedies

7.1 What constitutes copyright infringement in your jurisdiction?

Copyright infringement constitutes any of the following acts:

- using without authorisation the exclusive rights of the copyright owner, whether in relation to the whole or a substantial part of the copyrighted work;

- permitting a place to be used for infringing purposes on a profit basis; or

- displaying or exhibiting in public by way of trade, distributing for the purpose of trade or importing infringing copies of a work.

7.2 Is secondary liability for copyright infringement recognised in your jurisdiction? If so, how is it incurred? Are safe harbours afforded to intermediaries or others? If so, what are the requirements for such safe harbours to apply?

Sections 51(a)(ii) and 51(b) of the Copyright Act constitute the statutory basis for secondary liability in India. For a case of secondary infringement, it must be proved that there was a case of direct copyright infringement by another party. Further, secondary infringement can be classified as either contributory infringement or vicarious infringement. A primary or vicarious infringer may or may not be aware of the infringement, whereas a secondary infringer has knowledge of the infringement. Thus, for a case of secondary infringement to be made out:

- intent and/or knowledge on the part of the secondary infringer as to the occurrence of infringement is material; and

- any indirect involvement or contribution that violates the rights of the copyright owner in a work with such knowledge or intent, either express or implied, will constitute secondary infringement.

The IT Act, 2000 affords conditional immunity to intermediaries by virtue of the safe harbour principle. Section 79 provides that internet intermediaries are immune as long as:

- the intermediary has not abetted, aided or induced the commission of an unlawful act; and

- on receiving knowledge or on being notified by the appropriate government or its agency that any information, data or communication link residing in or connected to a computer resource that is in its control has been used to commit an unlawful act, the intermediary removes access to the material on that resource.

Intermediaries are immune from copyright violations as long as they adhere to the conditions set out in Section 79.

7.3 Is criminal enforcement of copyright law possible in your jurisdiction?

Yes – these can range from imprisonment, fines and seizure of infringing copies to delivery of infringing copies to the copyright owner.

7.4 What is the statute of limitations for copyright infringement?

The limitation period for filing suit is three years from the date of the infringement. Where the cause of action for filing a suit for copyright infringement is recurring or continuing in nature, the limitation period of three years will commence on the date of the last infringement.

7.5 Who has standing to bring copyright claims?

Apart from the copyright owner, an exclusive licensee can also bring a claim for infringement.

7.6 What is the procedure for pursuing claims for copyright infringement, including usual timeframes for resolution? Are there any streamlined administrative procedures for handling disputes?

Both civil and criminal claims can be pursued in respect of copyright infringement.

Civil action: A civil action involves the filing of a lawsuit seeking relief of injunction, damages, accounts or similar against the infringer. This entails filing a statement of claim together with an application seeking an interim injunction and documents before a competent court of law. Adjudication on the interlocutory application may take anywhere from one to two months to three to six months. For inter partes arguments, it may take between six months and one year. This varies across different jurisdictions in India, depending on issues such as:

- the discretion of the adjudicating authority; and

- the complexity of the matter.

Complete adjudication of a suit (ie, after trial) may take from three to five years, depending on issues such as:

- the jurisdiction; and

- the complexity of the matter.

Ex parte relief can be secured in a matter of days.

Criminal action: A criminal action involves filing a complaint with the police, who will undertake raids/search and seizure operations and thereafter file a report (also called a 'charge sheet') with the (criminal) court, pursuant to which prosecution of the case will be taken over by the state. The rights holder need not join the post-raid proceedings unless called upon by the court to do so. The decision to voluntarily join post-raid proceedings should be guided by the nature of the entity which was the target of the raid – for example:

- whether it made a significant contribution to the trade; or

- whether it was a small retailer.

The search and seizure operation is concluded within two to three weeks of receiving all paperwork. Complete adjudication of the criminal complaint may take between five and seven years.

Administrative remedies consist of:

- moving the registrar of copyrights to ban the import of infringing copies into India where the infringement is by way of importation; and

- ordering delivery of the confiscated infringing copies to the copyright owner.

7.7 What fees and costs are usually incurred in infringement actions?

No answer submitted for this question.

7.8 What typical defences are available to a defendant in copyright litigation?

Any activity that falls under the scope of fair use or similar provisions can be cited as a defence to copyright infringement, such as fair dealing in any work for private or personal use, including:

- research/criticism or review/reporting of current events or current affairs;

- reproduction of work by a teacher or pupil in the course of instructions;

- reproduction of any work for the purpose of judicial proceedings or its reporting;

- reading and recitation in public of reasonable extracts from a published literary or dramatic work; or

- storage of work in any medium by electronic means by a non-commercial public library for preservation if the library already possesses a non-digital copy of the work.

These are set out under Section 52 of the Copyright Act.

As part of the defence, one may also:

- challenge or dispute the originality of the work;

- claim independent creation; or

- argue:

-

- lack of access to the copyrighted work; or

- lack of knowledge of infringement (ie, if it can be shown that, on the date of the alleged infringement, the party was not aware and had no reasonable grounds to believe that copyright subsisted in the work).

Furthermore, in case of criminal complaints, if the offence was not committed for commercial gain, the degree of fine/imprisonment may be reduced.

7.9 What civil and criminal remedies are available against copyright infringement in your jurisdiction? Are customs enforcement measures available to halt the import or export of infringing works?

See question 7.6.

7.10 Are damages available for copyright infringement? Are statutory damages available, and if so, in what ranges? What factors will the court consider in determining the quantum of damages?

Yes, damages are available in civil proceedings. The grant of damages is intended to restore the plaintiff to the position which it would have been in had the infringement in question not taken place. Calculating damages involves determining the loss caused to the claimant by the infringement. Punitive damages can be awarded in addition to basic amounts, especially if the act of infringement was grave or flagrant. Damages can also be exemplary in order to serve as a deterrent to others. All or some of the profits made by a defendant through the sale of the infringing copies may also be granted to the claimant as the court may, in the circumstances, deem reasonable. Litigation costs may also be awarded at the discretion of the court.

In the past few years, the Indian courts have developed a regular practice of granting damages and monetary awards in IP suits. The Delhi High Court Intellectual Property Rights Division Rules, 2022 list various factors for determining the quantum of damages, including:

- lost profits suffered by the injured party;

- profits earned by the infringing party;

- the quantum of income that the injured party may have earned through royalties and/or licence fees had the use of the IP rights been duly authorised;

- the duration of the infringement;

- the degree of intent or neglect underlying the infringement; and

- the conduct of the infringing party to mitigate the damages incurred by the injured party.

In granting damages, the courts analyse not only the rights of the parties, but also broader surrounding factors, such as:

- the impact of infringing products on public health and safety; and

- the need for higher costs to deter a habitual offender or curb a bad-faith attempt to free ride on another's goodwill and reputation.

In cases of concealment and contempt, the courts are coming down heavily on parties and imposing high costs.

For instance, in Koninlijke Philips v Amazestore (CS(COMM) 737/2016 & IA 7469/2016), the High Court of Delhi set out the following formula to calculate aggravated damages focusing on the bad-faith conduct of a third party:

| Degree of bad-faith conduct | Proportionate award |

|---|---|

| First-time innocent infringer | Injunction |

| First-time knowing infringer | Injunction + partial costs |

| Repeated knowing infringer that causes minor impact to the plaintiff | Injunction + costs + partial damages |

| Repeated knowing infringer that causes major impact to the plaintiff | Injunction + costs + compensatory damages |

| Infringement that was deliberate and calculated (gangster/mafia/scam) plus wilful contempt | Injunction + costs + aggravated damages (compensatory + additional damages) |

The Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Division Appellate Division of High Courts Act 2015 introduced amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure and specifically:

- provides for the payment of costs (eg, legal fees and expenses incurred in connection with the proceedings); and

- lays down:

-

- the scenarios in which costs are to be paid; and

- the method of calculation of costs.

7.11 What is the procedure for appealing a decision in copyright litigation?

Where a first-instance judgment is passed by a district court, an appeal may be instituted in the high court. Where the first-instance judgment is passed by a single judge of the high court, the appeal is to be filed before the division bench of the high court. Thereafter, an appeal can be filed against the division bench decision before the Supreme Court.

In case of the seizure and disposal of infringing copies, an aggrieved person may challenge the order of the magistrate and file an appeal in the court of session. An appeal against a decision of the registrar of copyright can also be filed with the high court, which can then be appealed before a division bench of the high court and thereafter before the Supreme Court.

7.12 Do any special enforcement regimes apply to specific types of works (eg, digital and online content) in your jurisdiction?

No specific regimes apply to any particular category of work insofar as copyright enforcement is concerned.

7.13 What measures can copyright owners take to help prevent infringement of their rights in your jurisdiction?

Certain deterrent measures could prove useful for copyright owners – for instance:

- registering the copyright (although this is not necessary);

- issuing proper notification of the copyright to the public;

- monitoring the activities of habitual infringers;

- making independent contractors and employees subject to confidentiality;

- addressing takedowns and cease and desist notices vigilantly and actively against misuse; and

- publicising a successful civil or criminal action in order to send out a strong message.

8 Licensing

8.1 What types of copyright licences are available in your jurisdiction?

As per the Copyright Act, voluntary, compulsory and statutory licensing are recognised:

- Voluntary licensing empowers the owner to grant any interest in the right by licence.

- Compulsory licences may be granted for:

-

- works withheld from the public;

- work of untraceable authors; and

- the benefit of the disabled.

- Cover versions, broadcasts of literary and musical works and sound recordings, and licences to produce and publish translations and reproduce and publish works for certain purposes, may be awarded statutorily.

8.2 What terms do licences typically include (both express and/or implied licences)?

A copyright licence must be executed in writing and will generally address matters such as:

- identification of the work and details of the parties involved;

- the type of licence;

- a description of the rights;

- the duration of the licence;

- the geographical/territorial extent of the licence;

- the royalty or other consideration payable; and

- any restrictions.

8.3 Does your jurisdiction have collective management regimes for copyrights or other subject matter? If so, how does collective administration generally operate and who are the key players?

Yes, the Copyright Act recognises the concept of copyright societies. Ordinarily, only one society is registered to do business in respect of the same class of work. A copyright society can issue or grant licences in respect of:

- any work in which copyright subsists; or

- any other right given by the Copyright Act.

The business of issuing or granting a licence in respect of literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works incorporated in cinematographic films or sound recordings may be carried out only through a copyright society duly registered under the Copyright Act. This is a kind of compulsory collective licensing for the management of performing rights.

A copyright society may issue licences and collect fees in accordance with its scheme of tariff in relation only:

- to such works as it has been authorised to administer in writing by the authors and other rights holders; and

- for the period for which it has been so authorised.

The distribution of fees collected will be subject to a deduction not exceeding 15% of the collection on account of administrative expenses incurred by the copyright society.

In India, many copyright societies are registered to oversee different categories of copyrighted works, including:

- the Indian Reprographic Rights Organisation, for reprographic (photocopying) works;

- M/S Recorded Music Performance Limited, for sound recordings;

- CINEFIL Producers Performance Ltd, for cinematographic works; and

- the Indian Performing Right Society Limited, for musical works.

Additionally, Phonographic Performance Limited and Novex Communications Private Limited grant licences for musical works even though they are not formally registered as copyright societies.

8.4 Are compulsory licences recognised in your jurisdiction, including with respect to digital/online intermediaries? If so, what types are available and what are their key features?

Compulsory licences may be granted for:

- works withheld from the public;

- works of untraceable authors; and

- the benefit of the disabled.

Compulsory licences for intermediaries are not expressly recognised under the Copyright Act.

8.5 Is there a formal system for establishing collective management tariffs? If so, please describe the framework for negotiating and establishing tariffs.

The Copyright Act requires that every copyright society publish its tariff scheme. However, the act is silent on any formal system of establishing the tariffs and the negotiations fall upon the authors/owners and the copyright society.

A copyright society must set out a distribution scheme that explains the procedure for the distribution of royalties specified in the tariff scheme among its members. The distribution should be proportionate to the royalty income of the copyright society derived from the grant of licences for rights or sets of rights in each specific categories of works which it handles. There must be no discrimination between authors and other rights holders in relation to the distribution of royalties. The distribution scheme should ensure that all royalty distributions are:

- fair;

- accurate;

- cost effective; and

- without any unknown or hidden cross‐subsidies.

The distribution of royalties should be based on actual use or reliable statistical data that fairly represents the commercial exploitation of the licensed rights. The distribution scheme should ensure that royalties to all members are distributed at least once a quarter.

8.6 Can or must copyright licences be officially recorded in your jurisdiction?

No, copyright licences are not officially recorded in India under the Copyright Act.

8.7 Are there any specific requirements for the validity of a copyright licence in your jurisdiction? Are there any special provisions governing sub-licensing?

A copyright licence must be executed in writing. A typical licence will generally address matters such as:

- identification of the work and details of the parties involved;

- the type of licence;

- a description of the rights;

- the duration of the licence;

- the geographical/territorial extent of the licence;

- the royalty or other consideration payable; and

- any restrictions.

The Copyright Act does not expressly contain any regulations/provisions on sublicensing.

9 Protection of foreign copyright

9.1 Are foreign copyrighted works protected in your jurisdiction? If so, how and under what conditions (eg, rule of the shorter term)?

In 1999, the government passed the International Copyright Order, which makes the Copyright Act applicable to all works first made or published in a Berne Convention or Universal Copyright Convention country, in like manner, as if they were first made or published in India. The term of protection, however, is limited to that enjoyed in the country of origin.

9.2 What key concerns and considerations should be borne in mind by foreign copyright holders in seeking to protect their works in your jurisdiction?

India is a member of the Berne Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention, which provide for automatic copyright protection upon creation. While registration is not mandatory, it serves as prima facie evidence of copyright ownership. Formal registration may be sought from the Copyright Office. It is advisable that copyright registration be sought soon after the work comes into existence, as documents such as deeds of assignment and no-objection certificates must be signed by the author and/or the agency in which the author may be employed. The relevant persons may not be traceable or may be unavailable to sign documents at a later date.

10 Trends and predictions

10.1 How would you describe the current copyright landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? Are any new developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms?

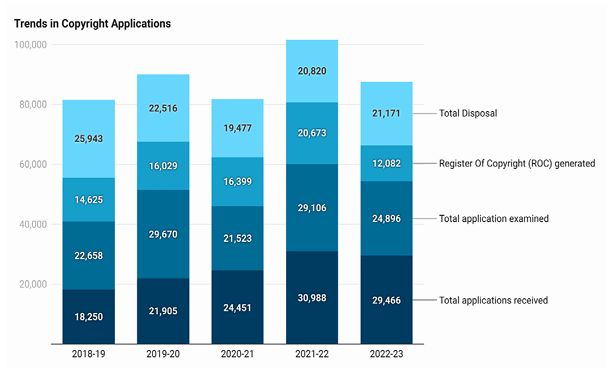

https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/IPOAnnualReport/1_114_1_ANNUAL_REPORT_202223_English.pdf

- Efforts have been made to enhance the operations of the Copyright Office by:

-

- implementing digitalisation;

- restructuring registration procedures;

- increasing staff capacity; and

- updating the website.

- To enhance transparency and engage stakeholders more effectively:

-

- the Copyright Office has started publishing received applications, disposals and pending cases on its website; and

- a dashboard has been developed to offer updates on the status of applications, granted registrations and the ability to search for registered works.

- The Copyright Office has implemented the option for individuals to file oppositions against applications for registration online.

- The Copyright Office has implemented a provision that allows for the uploading of soft copies of literary, dramatic and artistic works, as well as other relevant documents, on its online portal, with the aim of streamlining the registration process.

- The Copyright Office is in the process of enhancing accessibility to the public through virtual means. Efforts are underway to conduct copyright-related hearings virtually, eliminating the need for individuals to physically visit the office.

- The Copyright Office has conducted numerous seminars aimed at educating academics and students about copyright. The primary objective is to:

-

- inform the general public about copyright laws; and

- enhance their understanding of the registration process and procedures.

10.2 Have there been any recent legislative amendments or decisions involving copyright and generative AI, data or databases? If so, please summarise the current state of the law.

In Arijit Singh v Codible Ventures [SCC OnLine Bom 2445, 26 July 2024], the Bombay High Court restrained third parties from violating the personality rights of well-known Bollywood singer Arijit Singh and issued a ground-breaking ruling on AI-driven voice cloning. Singh is a renowned playback singer in the Indian film industry with a discography of more than 661 songs and 107 awards. He claimed that the legally protectable facets of his personality include:

- his name;

- his voice, vocal style and technique;

- his mannerisms and manner of singing;

- images, photographs, caricatures and likenesses of him; and

- his signature.

Singh claimed that misappropriation of any of these attributes for commercial purposes would violate his personality and publicity rights. In the infringement case by Singh, he alleged that:

- AI tools were being used to synthesise artificial recordings of his voice;

- the defendants had advertised his likeness to misrepresent and confuse prospective attendees about his endorsement of or performances at their virtual events;

- merchandise bearing his name, image, caricature and likeness had been created and sold on various websites, including Amazon and Flipkart;

- platforms had been developed to create, store, search for and share GIFs of Singh and his performances; and

- domain names bearing his name – including 'arijitsingh.com' and 's bearing his name – including 'arijitsingh.com' and 'arijitsingh.in' – had been registered without authorisation.

The court recognised Singh's widespread fame and reputation in India as markers of celebrity and held that the defendants had leveraged his popularity for financial gain by attracting consumers and driving traffic to their websites and AI platforms.

In previous cases, the Indian courts have recognised celebrity status and identified unauthorised commercial use of certain traits as an attack on personality rights – examples include:

- Karan Johar v Indian Pride Advisory;

- Anil Kapoor v Simply Life India;

- Amitabh Bachchan v Rajat Nagi;

- DM Entertainment v Baby Gift House; and

- Applause Entertainment Private Limited v Meta Platforms.

In light of this, the Bombay High Court ruled that:

- Singh's personality attributes – including his name, voice, photograph and likeness – were protectable elements; and

- the unauthorised creation of merchandise, domains and GIFs was illegal.

The use of AI tools to recreate Singh's voice and likeness – apart from violating his exclusive right to commercially exploit his personality – could potentially jeopardise his career if used for defamatory or nefarious purposes. The court thus granted an interim injunction prohibiting third parties from using Singh's name, voice, vocal style and techniques, mannerisms, photographs, images, signature, persona or any other aspect of his personality for any commercial or personal purposes without his explicit consent. Significantly, the injunction extended across all media, including physical, digital and the metaverse, to cover online platforms, publications, ads, merchandise and domain names, as well as AI-generated content, voice conversion technologies, digital avatars, deepfakes and GIFs. Further, this injunction was dynamic, meaning that it remains in force to ensure that the original injunction operates effectively. This aims to tackle repeat infringement, particularly in the online space (eg, mirror websites).

In Aaradhya Bachchan v Bollywood Time [CS (COMM) 230/2023], the Delhi High Court addressed the circulation of false and misleading information about the first named plaintiff, who is the daughter of celebrities Abhishek Bachchan and Aishwarya Bachchan. The plaintiffs argued that certain videos on YouTube falsely claimed that Aaradhya Bachchan was critically ill or deceased, violating her right to privacy and her IP rights. The plaintiffs contended that intermediaries such as YouTube should proactively remove such content, citing amendments to the Intermediary Guidelines Rules. The defendants, including YouTube, argued that they have no control over the content posted on their platforms and can only take action upon receiving complaints. They emphasised that they follow a zero-tolerance policy for certain types of content; but for other types of content, they must rely on user complaints.

In a decision issued on 20 April 2023, the court ruled in favour of the plaintiffs, restraining the identified YouTube channels from creating and publishing false videos about Bachchan. It directed YouTube to immediately delist the identified videos and provide details of the defendants to the plaintiffs. The court also instructed YouTube to take down any similar videos reported by the plaintiffs in the future. Additionally, it directed the central government to prohibit access to such content. The court emphasised:

- the importance of protecting the privacy and wellbeing of children, regardless of their parents' celebrity status; and

- the seriousness of disseminating misleading information about a child's health.

In summary, the court granted ad interim relief to the plaintiffs, acknowledging the prima facie case in their favour and emphasising the urgency of preventing further harm.

In Anil Kapoor v Simply Life India [CS (COMM) 652/2023 and IA 18237/2023-18243/2023], the Delhi High Court examined the misuse of Anil Kapoor's personality rights online. Renowned Indian actor Anil Kapoor filed suit to protect his name, image, likeness and various attributes of his personality against misuse by several defendants. The defendants were accused of utilising various features of Kapoor's persona in malicious ways without his consent, ranging from false endorsements to the sale of merchandise bearing Kapoor's image.

In a decision issued on 20 September 2023, the court acknowledged Kapoor's extensive career and the commercial value associated with his persona. It recognised Kapoor's rights to his name, voice, image and other elements of his personality, including the popularisation of the term 'Jhakaas', which was synonymous with his energetic persona. The court observed that the unauthorised use of Kapoor's persona for commercial purposes constituted a violation of his personality rights, publicity rights and copyright. It emphasised that such actions could adversely affect Kapoor's reputation and livelihood.

The court granted an ex parte injunction in favour of Kapoor, recognising his prima facie case and the potential irreparable harm caused by the defendants' actions. It held that Kapoor's rights deserved protection to safeguard his dignity and reputation, as well as the interests of his family and friends. In summary, the judgment underscored the importance of protecting celebrities' personality rights and upheld Kapoor's right to control the use of his name, image and likeness, particularly in commercial contexts, to prevent unauthorised exploitation and potential harm to his reputation.

10.3 Have there been any recent developments involving intermediary safe harbour and liability in your jurisdiction?

On 20 September 2024, the Bombay High Court struck down a proposed amendment to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 ('IT Rules'), which would empower the central government to establish fact-check units (FCUs) to identify "fake, false or misleading" information about government business on online platforms and have this taken down by intermediaries (Kunal Kamra v Union of India, Writ Petition 9792/2023). The amendment was held to be unconstitutional and in violation of fundamental rights and the principles of natural justice.

In 2023, the IT Rules were sought to be amended so as to introduce FCUs set up by the government to regulate digital content that the FCUs deemed to be "fake, false or misleading". This was captured under Rule 3(1)(b)(v) of the amendments as follows:

Rule 3(1) - Due diligence by an intermediary: Any intermediary, including [a social media intermediary, a significant social media intermediary and an online gaming intermediary], shall observe the following due diligence while discharging its duties, namely:-

(b) the intermediary shall inform its rules and regulations, privacy policy and user agreement to the user in English or any language specified in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution in the language of his choice and shall make reasonable efforts by itself, and to cause the users of its computer resource to not host], display, upload, modify, publish, transmit, store, update or share any information that,-

(i)........ to (iv)........

(v) deceives or misleads the addressee about the origin of the message or knowingly and intentionally communicates any misinformation or information which is patently false and untrue or misleading in nature or, in respect of any business of the Central Government, is identified as fake or false or misleading by such fact check unit of the Central Government as the Ministry may, by notification published in the Official Gazette, specify.

The IT Act, 2000 contains safe harbour provisions (Section 79) that exempt intermediaries from liability for content hosted by them, provided that they observe due diligence. As a natural corollary, failure to comply with proposed Rule 3(b)(1)(v) would threaten the safe harbour protection enjoyed by intermediaries.

Following the announcement of this amendment, Indian comedian Kunal Kamra filed a writ petition in the Bombay High Court challenging the amendment as unconstitutional. The Editors Guild of India and the Association of India Magazines followed suit with similar petitions challenging Rule 3(1)(b)(v) on the grounds that it violates the fundamental right to equality, speech and liberty under the Indian Constitution. All these petitions were clubbed together for hearing before a division bench of the Bombay High Court.

The division bench of the Bombay High Court, comprising two judges (Justice GS Patel and Justice Neela Gokhale), presided over the batch of writ petitions challenging Rule 3(1)(b)(v) and delivered a split verdict in January 2024. The core question raised by the writ petitions was whether it was constitutional to take away the safe harbour afforded to intermediaries if they did not remove:

- content that was found to be patently false and untrue or misleading; or

- "false, fake or misleading" content concerning "any business of the central government" as identified by an FCU.

Justice Patel struck down the amendment as being unconstitutional and in violation of the IT Act, while Justice Gokhale upheld its validity.

Due to this difference in opinion, the matter was placed before a third judge, Justice Chandurkar, who sided with Justice Patel and held the impugned rule to be unconstitutional. The key issues considered were as follows:

- False speech and free speech: The division bench judges disagreed about whether false speech could be restricted under the Indian Constitution. Justice Patel held that under the right of free speech, there is no further "right to the truth". Thus, mere falsity does not allow speech to be restricted and the impugned rule thus sought to restrict content on a ground that the Indian Constitution does not recognise. In contrast, Justice Gokhale held that the right to free speech is a right to the truth and that false content cannot enjoy freedom of speech. Justice Chandurkar sided with Justice Patel and rejected the claim that mere falsity constitutes valid grounds for restriction and that it is not the responsibility of the state to ensure that citizens are entitled only to information that has been identified by FCUs as not being "false, fake or misleading". Justice Chandurkar took the view that the Indian Constitution already lists the grounds on which speech can be restricted – such as in relation to the security and integrity of India, public order or defamation – and that falsity is not encapsulated therein.

- Reading down the impugned rule: On the prospect of reading down the impugned rule, Justice Gokhale suggested that:

-

- the impugned rule, when considered in its entirety, merely required an intermediary to make a "reasonable effort" in order to avoid losing the safe harbour; and

- the option of a disclaimer rather than a takedown would still be available as a means of reasonable effort.

- It was Justice Gokhale's view that since political satire, parody, criticism, opinion, views and similar do not constitute offensive information, the impugned rule did not overreach. However, Justice Patel saw the rule as overreaching and disagreed, holding that excluding any opinion, view, commentary, parody or criticism from the ambit of "information" would be impermissible and a disclaimer would not be enough given that the impugned rule carries a positive obligation – that is, "not to host". Justice Chandurkar rejected Justice Gokhale's claims and agreed with Justice Patel that the scope of the impugned rule could not be said to be restricted to facts only; it would also invariably affect political views, satire, opinion – that is, 'information' in general.

- Equality, proportionality and natural justice: Justice Patel took the view that the impugned rule violated natural justice principles and the right to equality as members of the FCUs, selected and appointed by the central government, would assess the veracity of information. This would make the central government a judge in its own case. Justice Gokhale, on the other hand, held that there was no rational basis to impute a pre-emptive bias upon FCU members due to their appointment by the central government. Justice Gokhale also stated that even after the FCUs had issued a decision, there were adequate safeguards for a party to approach an appellate body or court which would serve as the final arbiter. Justice Chandurkar sided with Justice Patel and held that unilateral determination by the central government violated principles of equality and merely having a forum for further appeal was not a safeguard. He also reiterated that equality was further violated as the rigour of the scrutiny sought to be imposed by the impugned rule on digital media was not the same as that imposed on print media, and this was seen as unequal treatment of different forms of media and profession. He further held that the impugned rule lacked meaningful and proportionate safeguards, as well as transparency, with respect to:

-

- the operation and constitution of the FCUs; and

- the criteria for determining what constituted "false, fake or misleading" information.

- Due to this vagueness, the due diligence expected of an intermediary was not proportionate or reasonable, which in turn would chill free speech.

Therefore, the third judge held that the impugned rule was liable to be struck down as being unconstitutional and accordingly, the rule was struck down.

11 Tips and traps

11.1 What are your top tips for protecting copyrighted works in your jurisdiction and what potential sticking points would you highlight?

The protection of copyrighted works in India involves several steps and considerations. Our top tips include the following:

- While copyright protection is automatic upon creation of the work, registration with the Copyright Office is strongly recommended. It serves as prima facie evidence of ownership and facilitates enforcement actions.

- Display copyright notices on your works to alert others of your rights. Include:

-

- the symbol ©;

- the year of publication; and

- the copyright owner's name.

- Expressly outline the terms under which a licence can use your copyrighted work and regularly monitor (unauthorised) use of your copyrighted works. Digital tools and services may be utilised to track unauthorised use and take appropriate action to enforce your rights.

- Ensure that stakeholders understand the importance of copyright protection and their responsibilities in respecting copyrighted works.

- Copyright laws and regulations change and develop over time. Stay updated on developments in copyright law to ensure compliance and maximise protection.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.