In Australia, each state and territory has legislative provisions that govern private client matters.

Each jurisdiction within Australian generally has the following laws:

- Trustee Acts, which govern trusts and the rights and duties of trustees;

- Wills Acts or Succession Acts, which govern the creation and interpretation of wills;

- Administration Acts or Administration and Probate Acts, which govern probate matters and the administration of deceased estates, and which allow certain people to make a claim for provision from a deceased person’s estate;

- Guardianship and Administration Acts, which oversee the financial and personal decisions of persons who have lost capacity;

- Power of Attorney Acts, which govern the making and operation of powers of attorney;

- Family Law Acts, which govern matrimonial matters; and

- various Duties Acts and Tax Acts, which govern duties payable on the transfer of dutiable assets and various taxes associated with the transfer of assets, whether through a deceased estate or otherwise.

The laws in each state and territory vary slightly, and usually the domicile of the deceased or the location of any real property will determine which laws are applicable.

There are no special regimes that apply to specific individuals in Australia. Generally, a person’s residency status determines his or her exposure to income tax and other taxes in Australia on income derived in Australia and elsewhere.

However, surcharges may apply depending on the status of a person’s residency, such as foreign purchaser surcharge duty on the acquisition of residential property.

There are numerous bilateral, multilateral and supranational instruments in effect in Australia which are relevant in the private client sphere. Australia has over 50 double tax agreements with other countries which provide for either income tax exemptions or reduced rates.

Australia has also entered into bilateral agreements with a number of countries in relation to the exchange of information in relation to taxes.

Australia has enacted the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (MLI), which it signed on 7 June 2017. The MLI has been ratified, which means that it applies to ‘covered countries’ such as Belgium, Canada, France, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Singapore and the United Kingdom.

Other important agreements to which Australia adheres and which affect private clients include:

- the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Cth); and

- the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth).

There are four tests to determine whether a person is an Australian tax resident. These are outlined as follows.

Residency status: The commissioner of taxation will consider the following:

- physical presence;

- intention and purpose;

- the location of your family;

- business or employment ties;

- maintenance and location of assets; and

- social and living arrangements.

If an individual does not satisfy the residency test, he or she may still be considered an Australian tax resident if any of the statutory tests below are satisfied:

- Domicile test: The domicile test assesses an individual’s permanent residence. If the commissioner is satisfied that an individual’s permanent home is located in Australia, he or she will be liable to pay tax in Australia.

- 183-day test: If an individual spends at least 183 days per calendar year in Australia, whether continuously or not, the individual will be considered an Australian tax resident.

- Superannuation test: An individual will be considered an Australian tax resident if he or she, or his or her spouse, is a contributing member of a public sector superannuation scheme of the Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme.

If the commissioner is satisfied that an individual is an Australian tax resident, he or she may be required to pay:

- income tax;

- land tax on any real property owned by the individual, subject to exemptions for a principal place of residence;

- goods and services tax; and

- capital gains tax.

In Australia, the personal tax year is referred to as a financial year. The financial year runs from 1 July to 30 June of each year.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Australian tax residents must pay income tax on their personal taxable income, including from employment, business interests, dividends, trust distributions, foreign income and the like.

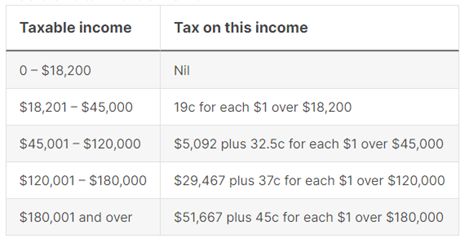

The marginal income tax rate increases according to the level of income earned. For the 2023–2024 financial year, the marginal income tax rates are as follows.

For the 2024–2025 financial year, the proposed changes to marginal income tax rates are as follows:

- Reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%;

- Reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%;

- Increase the threshold above which the 37% tax rate applies from A$120,000 to A$135,000; and

- Increase the threshold above which the 45% tax rate applies from A$180,000 to A$190,000.

The above rates do not include the Medicare levy of 2%, which is payable to fund Medicare, the national healthcare provider in Australia.

High-income earners may also be liable to pay the Medicare levy surcharge (MLS), an additional levy payable by individuals who reach a certain level of income and do not have private health insurance. In this instance, the government imposes a further levy which is calculated at approximately 1% to 1.5% of the individual’s taxable income over and above the existing Medicare levy of 2%.

The MLS encourages those who can afford private health insurance to obtain appropriate health coverage for themselves and their dependants, thus reducing the financial burden on Medicare.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The calculation of taxable income depends on its nature.

An employee is generally taxed on all remuneration and benefits received in the relevant tax year. A company’s contributions to an employee’s superannuation scheme are generally not taxable.

Further, net profits from rental property after the deduction of qualifying expenses which were incurred wholly and exclusively for the property rental business are also added to an individual’s income for that financial year. The types of expenses that can be deducted include:

- mortgage interest;

- the costs of general maintenance and repairs to the property (provided that they are not improvements);

- utility costs;

- insurance;

- letting agent fees and management fees; and

- accountant’s fees.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

An Australian tax resident must file an income tax return on a self-assessment basis where his or her gross income exceeds the tax-free threshold of A$18,200. A non-resident earning more than A$1 of Australian-sourced income must file a return. There is no joint assessment or joint filing in Australia.

The tax return is due for filing by the following 31 October, unless an extension is available.

Once a tax return is lodged, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) will issue an income tax assessment of the taxable income/tax loss and tax payable (if any) to the individual based on the income tax return. If there is a tax liability, it is usually payable by May before the commencement of the next financial year.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

In Australia, the first A$18,200 of income earned is considered tax free. Every A$1 earned over the A$18,200 is taxable. There are certain deductions and reliefs available, such as the following:

- Income from rental properties is taxed only after the deduction of costs and expenses for operating the rental property;

- There is a deduction for out-of-pocket work-related expenses; and

- There are deductions for:

-

- the cost of managing tax affairs;

- charitable donations to registered charitable organisations; and

- interest, dividend and other investment income.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

An individual is liable to pay capital gains tax (CGT) on the profits generated upon disposal of an asset. Any CGT payable will form part of an individual’s income tax and will be assessed at the marginal income tax rates.

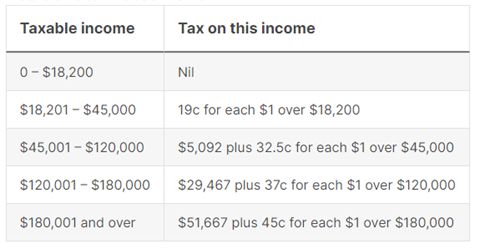

For the 2023–2024 financial year, the marginal income tax rates are as follows:

For the 2024–2025 financial year, the proposed changes to marginal income tax rates are as follows:

- Reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%;

- Reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%;

- Increase the threshold above which the 37% tax rate applies from A$120,000 to A$135,000; and

- Increase the threshold above which the 45% tax rate applies from A$180,000 to A$190,000.

Any income generated by a company is taxed at a marginal rate of 30%; and for trusts, any income accumulated (not distributed to beneficiaries) is taxed at a marginal rate of 45%.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

CGT is calculated by first determining the cost base of the asset. The cost base is what it cost to acquire the asset, together with the costs incurred in acquiring, holding and disposing of the asset. Once the cost base has been determined, these costs are subtracted from the amount received on disposal of the asset. Capital losses can be subtracted from capital gains.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

An Australian tax resident must file an income tax return on a self-assessment basis where his or her gross income exceeds the tax-free threshold of A$18,200. A non-resident earning more than A$1 of Australian-sourced income must file a return. There is no joint assessment or joint filing in Australia.

Gross income includes any capital gains made on the disposal of an asset.

Once a tax return is lodged, the ATO will issue an income tax assessment of the taxable income/tax loss and tax payable (if any) to the individual based on the income tax return. If there is a tax liability, it is usually payable by May before the commencement of the next financial year.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

A 50% CGT discount is available on a capital gain if the individual owned the asset for at least 12 months and is an Australian tax resident.

Any costs in acquiring an asset are factored into the cost base calculations to determine the gain on a disposal of the asset.

Additional discounts of up to 10% are available for Australian individuals who provide affordable rental housing to people earning low to moderate incomes. On the disposal of such residential rental properties, the Australian homeowner could obtain a discount of up to 60%.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Australia does not impose an inheritance tax or estate tax at either the federal or state level. However, certain taxes may still apply indirectly when assets are transferred or disposed of following a person's death. These taxes vary by state and depend on the nature of the assets involved and how they are managed post-death. Some common taxes that may apply include Capital Gains Tax (CGT), Superannuation Death Benefits Tax, Income Tax on inherited assets, and state-based land taxes.

While CGT and Superannuation Death Benefits Tax apply uniformly across Australia (federal level), state-based taxes differ. Below is a breakdown of key tax considerations, including an overview of the Vacant Residential Land Tax and Land Tax specific to Victoria, Australia.

Capital Gains Taxes (CGT)

As outlined above, while there is no direct inheritance tax, Capital Gains Tax (CGT) may apply when a beneficiary disposes of inherited assets. Key considerations include:

- Main Residence Exemption:

-

- If the inherited asset is a main residence of the deceased and sold within two years of the deceased's date of death, it is typically exempt from CGT.

- If sold after two years, CGT may apply depending on how the property was used.

- Other Assets (e.g., Shares, Investment Properties):

-

- No CGT is triggered at the time of inheritance.

- CGT is calculated when the beneficiary sells the asset, based on the asset's cost base (usually the market value at the date of death for post-September 1985 assets).

- Pre-1985 Assets:

-

- Assets acquired by the deceased before 20 September 1985 are exempt from CGT until the beneficiary disposes of them.

- Upon disposal, only the gain from the date of the deceased's death is subject to CGT.

Executors and beneficiaries should seek tax advice to determine whether exemptions apply and to minimise CGT liabilities.

Superannuation Death Benefits Tax

Superannuation (retirement savings) is not automatically tax-free upon death. The tax treatment depends on the relationship between the deceased and the beneficiary:

- Tax-Dependent Beneficiary (e.g., spouse, minor child):

-

- Lump sum death benefits are tax-free.

- Non-Dependent Beneficiary (e.g., adult child):

-

- Taxable Component (Taxed Element): Currently taxed at 15% plus the Medicare levy (2%).

- Taxable Component (Untaxed Element): Currently taxed at 30% plus the Medicare levy (2%).

It is advisable to seek financial advice when handling superannuation death benefits to ensure compliance and tax efficiency.

Income Tax on Inherited Income-Producing Assets

During estate administration and following a distribution to beneficiaries of estate assets, income from inherited assets is subject to income tax:

- Estate Administration Period:

-

- Any income (e.g., rental income from investment properties, dividends from shares) earned before asset distribution is taxed within the estate.

- After Distribution to Beneficiaries:

-

- Income generated from inherited assets (such as rental income, dividends, or other earnings) is taxed at the beneficiary’s marginal tax rate.

Vacant Residential Land Tax (Victoria)

In Victoria, Australia a Vacant Residential Land Tax (VRLT) applies to certain properties that remain unoccupied for more than six months in a calendar year. This tax is designed to encourage property owners to make residential properties available for occupation.

When It Applies:

- The tax applies only to residential properties in specific council areas within Melbourne, Victoria.

- A property is considered vacant if it was unoccupied for more than six months in a calendar year.

- Short-term leases (e.g., Airbnb) generally do not count towards occupancy.

Rate:

- 1% of the property’s capital improved value (CIV) (as assessed by the council).

Exemptions:

- Properties occupied as a principal place of residence.

- Properties undergoing significant renovations or redevelopment.

- Newly acquired properties (first year exemption).

Executors of deceased estates should be mindful of VRLT obligations if a property remains unoccupied for an extended period.

Land Tax (Victoria)

Land tax is an annual tax imposed on landowners in Victoria based on the total taxable value of their landholdings, excluding exempt properties (e.g., a principal place of residence).

When It Applies:

- Land tax applies annually to landowners as of 31 December each year.

- It is assessed on the combined taxable value of all non-exempt land owned in Victoria.

- Inherited properties may be subject to land tax depending on their use and whether they qualify for exemptions.

Rates for 2024 (General Land Tax Scale):

| Taxable Value of Land | Tax Rate |

|---|---|

| Below $50,000 | No tax |

| $50,000 – $250,000 | $275 + 0.2% of value above $50,000 |

| $250,000 – $600,000 | $775 + 0.3% of value above $250,000 |

| $600,000 – $1,000,000 | $2,000 + 0.8% of value above $600,000 |

| $1,000,000 – $1,800,000 | $5,200 + 1.3% of value above $1,000,000 |

| $1,800,000 – $3,000,000 | $15,600 + 1.8% of value above $1,800,000 |

| Over $3,000,000 | $37,800 + 2.5% of value above $3,000,000 |

Exemptions & Considerations:

- The deceased estate may qualify for an exemption during the administration period.

- If a beneficiary inherits the property and uses it as their principal place of residence, land tax does not apply.

- If the property is rented out, land tax will apply.

Executors should consider land tax implications when managing or distributing estate properties in Victoria.

Summary of Applicable Taxes:

| Type of Tax | When It Applies | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Inheritance Tax | N/A (No inheritance or estate tax in Australia) | 0% |

| Capital Gains Tax (CGT) | On disposal of inherited assets | Marginal CGT rates (up to 45%) |

| Superannuation Death Benefit Tax | On death benefits paid to non-dependents | 15% – 30% + 2% Medicare levy |

| Income Tax | On income from inherited income-producing assets | Marginal tax rate |

| Vacant Residential Land Tax (Victoria) | If property remains vacant for more than 6 months in a calendar year | 1% of the property's capital improved value (CIV) |

| Land Tax (Victoria) | Annually on non-exempt land as of 31 December each year | Varies based on land value (see below for details) |

Proper estate planning can help minimise unexpected tax obligations for beneficiaries by raising these matters to the attention of the will-maker during the planning process so that careful consideration can be given to the overall consequences and impact that taxes can have on the ultimate distribution of an estate.

Similarly, executors and trustees should obtain professional tax advice during estate administration to ensure compliance with their tax obligations and avoid future unexpected tax liabilities. This is particularly important to complete before the final distribution of estate assets, as any tax obligations not correctly dealt with by the executor or trustees could become the personal responsibility of the executor or trustee.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

In Australia, while there is no inheritance tax, certain taxes like Capital Gains Tax (CGT), Superannuation Death Benefits Tax, and Income Tax may apply when inherited assets are sold or generate income. The taxable base applicable is determined differently depending on the specific type of tax:

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) – Taxable Base

The taxable base for CGT is the capital gain or loss realised when an inherited asset is sold. It is calculated as:

- Capital Gain (or Loss) = Sale Price − Cost Base

How the Cost Base is Determined:

- Post-20 September 1985 Assets (Subject to CGT):

-

- The cost base is market value at the date of the deceased's death.

- Pre-20 September 1985 Assets (Exempt Until Death):

-

- The cost base is market value at the date the beneficiary inherits.

Discounts:

- A 50% CGT discount may apply if the asset is held for more than 12 months before disposal.

Executors and beneficiaries should seek tax advice to determine whether exemptions apply and to minimise CGT liabilities.

Superannuation Death Benefits Tax – Taxable Base

Superannuation (retirement savings) is not automatically tax-free upon death. The tax treatment depends on the relationship between the deceased and the beneficiary:

- Tax-Dependent Beneficiary (e.g., spouse, minor child):

-

- Lump sum death benefits are tax-free.

- Non-Dependent Beneficiary (e.g., adult child):

-

- Taxable Component (Taxed Element): 15% tax + 2% Medicare levy.

- Taxable Component (Untaxed Element): 30% tax + 2% Medicare levy.

- Taxable Base for Superannuation Death Benefits Tax:

-

- The taxable base is the taxable component of the deceased’s superannuation payout.

- Formula: Taxable Base = Total Super Death Benefit − Tax-Free Component

- Tax-Free Component: Consists of non-concessional (after-tax) contributions and is not taxable regardless of the beneficiary.

- Taxable Component: Includes both taxed and untaxed elements, with applicable tax rates as mentioned above.

Income Tax on Inherited Income-Producing Assets – Taxable Base

When an inherited asset generates income (e.g., rent, dividends), the taxable base is the gross income earned from that asset.

Example:

- Rental Property: Taxable base = Total rental income – allowable deductions (e.g., interest, maintenance costs)

- Shares: Taxable base = Dividends received + franking credits (if applicable)

The income is then taxed at the beneficiary’s marginal tax rate.

Summary of Taxable Base Determination:

| Type of Tax | Taxable Base Formula | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Gains Tax (CGT) | Sale Price – Cost Base | Market value at death or inheritance (depending on asset type) |

| Superannuation Death Benefits Tax | Total Benefit – Tax-Free Component | Split between taxed and untaxed elements |

| Income Tax | Gross Income – Allowable Deductions | Depends on income source (rental, dividends, etc.) |

(c)What are the relevant tax return requirements?

In Australia, when a person passes away, their legal personal representative (LPR),typically the executor or administrator of the estate, is responsible for managing the deceased person's tax affairs. This includes lodging any outstanding tax returns and managing the tax obligations of the deceased estate. The following is a summary of the tax return requirements relevant to deceased estates:

Final Tax Return for the Deceased Person

The executor or administrator must lodge a final individual tax return and any tax returns not previously filed by the deceased, for the deceased up to the date of death.

Key Points:

- Period covered: The relevant tax year is from 1 July of the relevant financial year to the date of death.

- Income to Include:

-

- Employment income, pensions, annuities.

- Investment income (interest, dividends, rent).

- Capital gains on assets sold before death.

- Deductions: The same deductions apply as in a regular tax return, including work-related expenses and capital losses.

- Lodgement Due Date:

-

- Generally, the standard 31 October deadline applies.

- Executors may request a later date if needed.

Trust Tax Returns for the Deceased Estate

After the date of death, the estate becomes a trust for tax purposes. If the estate earns income while being administered (e.g., rental income, dividends, interest), the executor must lodge a Deceased Estate Trust Tax Return.

Key Points:

- Period Covered: From the day after death until assets are fully distributed.

- Income to Include:

-

- Rent, interest, dividends, capital gains.

- Tax-Free Threshold:

-

- First 3 income years:

-

- Up to $18,200 is tax-free.

- Marginal tax rates apply above this amount.

- After 3 years:

-

- Standard individual marginal tax rates apply from $1.

- Lodgement Due Date: Similar to individual tax returns (typically 31 October).

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) Obligations

While no CGT is triggered at the time of inheritance, a CGT event may occur if:

- The estate disposes of assets (e.g., sells shares or property).

- The beneficiary later sells inherited assets.

Reporting Requirements:

- Capital gains or losses must be declared in the relevant tax return (estate or beneficiary).

- CGT exemptions or discounts may apply, such as the main residence exemption or 50% CGT discount for assets held longer than 12 months.

Superannuation Death Benefits

Superannuation death benefits are generally tax-free if paid to a tax-dependent (e.g., spouse, minor child).

- If paid to a non-dependent, the taxable portion must be reported in the recipient non-dependent's tax return.

- Withholding tax may apply before distribution.

Disclosure Obligations and Reporting for Beneficiaries

In Australia, beneficiaries must report certain types of inherited income or capital gains in their own tax returns, including:

- Income from distributed estate assets (e.g., rent, dividends).

- Capital gains or losses when they dispose of inherited assets.

In addition, if beneficiaries are in receipt of government social security benefits, they may have additional reporting obligations to disclose to government agencies (Services Australia) following receipt of their inheritance to disclose a change in financial circumstances.

Summary of Tax Return Requirements

| Return Type | Who Lodges? | When Required? | What to Report? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final Tax Return for Deceased | Executor/Administrator | Up to date of death | Income, deductions, capital gains/losses |

| Deceased Estate Tax Return | Executor/Administrator | For each income year during estate administration | Income earned by the estate |

| Capital Gains Tax Reporting | Executor/Beneficiary | When assets are sold by estate or beneficiary | Capital gains/losses on disposal |

| Superannuation Death Benefits | Beneficiary | In the year benefit is received | Taxable portion of death benefit |

| Beneficiary’s Individual Return | Beneficiary | Ongoing as required | Income from inherited assets |

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

In Australia, although there is no inheritance tax, several exemptions, deductions, and reliefs may apply when dealing with deceased estates and inheritances. These can reduce or eliminate tax liabilities on capital gains, income, and superannuation death benefits. Some of the key relief that may be available:

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) Exemptions and Relief

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) may apply when inherited assets are sold, but several exemptions and concessions can reduce or eliminate the tax burden.

- Main Residence Exemption

-

- If the inherited property was the deceased’s main residence and not used to produce income, the sale is exempt from CGT if sold:

-

- Within 2 years of the date of death, or

- After 2 years, if the property was not used to produce income and other conditions are met.

- This exemption can be partially applied if the property was income-producing for some time.

- There are also some exemptions applicable where the deceased’s main residence dwelling ceased to be their dwelling because the deceased entered into aged care living.

- Pre-CGT Asset Exemption

-

- Assets acquired by the deceased before 20 September 1985 are exempt from CGT until the beneficiary sells them.

- When sold, only the capital gain from the date of the deceased’s death is taxable.

- 50% CGT Discount

-

- If the beneficiary holds the inherited asset for more than 12 months before selling, a 50% discount applies to the capital gain.

- Applies to assets such as shares, investment properties, and other non-personal-use assets.

- Small Business CGT Concessions

-

- If the deceased qualified for small business CGT concessions, beneficiaries may inherit the eligibility.

- Concessions include:

-

- 15-year exemption (full exemption if the business was held for 15+ years).

- 50% active asset reduction (halves the capital gain).

- Retirement exemption (up to $500,000 tax-free).

- Rollover relief (defers the capital gain).

Superannuation Death Benefits Tax Relief

Superannuation death benefits are tax-free under certain circumstances.

Exemption for Dependents

- Death benefits paid to a tax-dependent (spouse, minor child, financial dependent) are completely tax-free, regardless of the amount.

Lower Tax Rates for Non-Dependents

For non-dependents (e.g., adult children):

- Taxed Element: 15% + 2% Medicare Levy.

- Untaxed Element: 30% + 2% Medicare Levy.

- No tax is payable on the tax-free component.

Tax-Free Threshold for Deceased Estates

Deceased estates have a tax-free threshold for the first three income years, similar to individual taxpayers.

| Income Year | Tax-Free Threshold | Marginal Tax Rates Apply Above |

|---|---|---|

| 1–3 years | $18,200 | Standard individual rates |

| After 3 years | $0 | No tax-free threshold |

This provides temporary relief to the estate while assets are being administered.

Income Tax Deductions and Relief

The estate or beneficiaries may be able to claim deductions and offsets to reduce taxable income.

Allowable Deductions

- Interest on loans for income-producing inherited assets (e.g., investment property).

- Maintenance costs for inherited rental properties.

- Financial advisor fees related to administering the estate.

Other Relief and Concessions

Medicare Levy Exemption

- In certain cases, if the deceased was exempt from the Medicare Levy, this exemption continues for the final tax return.

Charitable Donations

- If the deceased left assets to a deductible gift recipient (DGR), such as a charity, the donation may be tax-deductible in the deceased’s final tax return.

Summary of Exemptions and Reliefs

| Type of Tax | Relief/Exemption | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Gains Tax (CGT) | Main residence exemption | Sold within 2 years of death |

| Pre-CGT asset exemption | Assets acquired before 20 Sep 1985 | |

| 50% CGT discount | Held for 12+ months before sale | |

| Small business CGT concessions | If deceased qualified | |

| Superannuation Death Benefits | Tax-free for dependents | Spouse, minor child, or financial dependent |

| Estate Income Tax | Tax-free threshold for 3 years | $18,200 per year |

| Deductions | Maintenance, interest, and admin costs | If income-producing |

| Medicare Levy | Exemption if deceased qualified | Applies to final tax return |

| Charitable Donations | Tax deduction for donations to DGRs | Applied in final tax return |

It is important that executors, administrators, trustees and beneficiaries obtain professional tax advice in relation to the tax affairs to ensure that they utilise available exemptions, roll-over relief and other minimise to reduce or eliminate their taxation liabilities where possible.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Tax on investment income is based on how the investments are owned. For example, assets may be owned by an individual, a company or a trust structure.

For investments owned in a personal capacity, the investment income is added to the individual’s overall income, including employment income, and taxed at the marginal income tax rates.

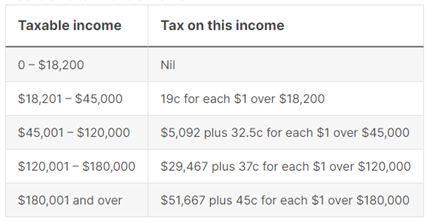

The marginal income tax rate increases according to the level of income earned. For the 2023–2024 financial year, the marginal income tax rates are as follows:

For the 2024–2025 financial year, the proposed changes to marginal income tax rates are as follows:

- Reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%;

- Reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%;

- Increase the threshold above which the 37% tax rate applies from A$120,000 to A$135,000; and

- Increase the threshold above which the 45% tax rate applies from A$180,000 to A$190,000.

Any income generated by a company is taxed at a marginal rate of 30%; and for trusts, any income accumulated (not distributed to beneficiaries) is taxed at a marginal rate of 45%.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The taxable base of investment income is calculated by classifying the investment income and deducting any related expenses incurred to earn that income.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

In the case of investment income for assets owned by an individual in his or her personal capacity, the individual must allocate such income to his or her individual tax return. An Australian tax resident must file an income tax return where his or her gross income exceeds the tax-free threshold of A$18,200. A non-resident earning more than A$1 of Australian-sourced income must file a tax return. There is no joint assessment or joint filing in Australia.

The tax return is due for filing by the following 31 October, unless an extension is available.

Once a tax return is lodged, the ATO will issue an income tax assessment of the taxable income/tax loss and tax payable (if any) to the individual based on the income tax return. If there is a tax liability, it is usually payable by May before the commencement of the next financial year.

A corporation – which includes the parent company of a tax consolidated group – can lodge a tax return under a self-assessment system that allows the ATO to rely on the information stated on the return. However, the ATO conducts audits to ensure that corporations are compliant with their tax requirements. If a corporation has doubts as to its tax liability regarding a specific item, it can request the ATO to consider the matter and issue a binding private ruling.

Generally, the tax return for a corporation must be filed with the ATO by 15 January or such later date as the ATO allows. Additional time may apply where the tax return is filed by a registered tax agent.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

As with a person’s income, in Australia, the first A$18,200 of income earned is considered tax free. Every A$1 earned over this threshold is taxable. There are certain deductions and reliefs available, such as for:

- income from rental properties – only income earned after the deduction of costs and expenses for operating the rental property is taxed;

- other expenses, such as the costs of managing one’s tax affairs; and

- dividend and other investment income.

Further deductions and relief are available for corporations, such as:

- depreciation and depletion for the decline in value held by the taxable entity;

- start-up expenses such as incorporation costs;

- interest expenses;

- bad or forgiven debts; and

- charitable contributions.

Losses can also be carried forward indefinitely, subject to certain compliance requirements.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Land transfer duty (also known as stamp duty), land tax, council rates and CGT are the main taxes which apply to an individual’s real property.

Stamp duty is tax payable upon the acquisition of real property. Stamp duty is calculated based on the dutiable value of the property and whether any concessions or exemptions are available. Different rates of stamp duty are generally payable by foreign residents. Concessions and/or exemptions are available in various circumstances, including:

- for eligible first-home buyers; and

- in other circumstances, such as transfers between spouses (or ex-spouses) or between trusts and beneficiaries.

An annual land tax is generally payable on the taxable value of real property. An individual’s principal place of residence is generally exempt from land tax.

Council rates are payable to the municipal council to cover the costs of local government services such as waste management. Council rates are calculated based on an assessment of capital improved value undertaken by the municipal council.

CGT is payable by the vendor upon the sale or disposal of dutiable property other than a principal place of residence.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

Taxes and duties relating to real estate are determined on a sliding scale depending on the value of the property. CGT is determined on the gain attributed from the purchase price less any costs for the maintenance of the property. The capital gain is then allocated to the company, trust or individual’s taxable income for that financial year.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

There are no specific tax return requirements; these taxes and duties should be accounted for in the individual, trust or company’s tax lodgements for each financial year.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

Land transfer duty exemptions are available for first-home owners in Australia, subject to satisfying certain requirements, such as:

- the property being the individual’s primary residence; and

- the value being under a threshold amount.

Land tax is not generally paid on primary residences.

Upon the sale of a primary residence, no CGT is payable; however, on disposal of any other real estate held for more than 12 months, a 50% discount of any taxable gain is available on the disposition. CGT may be rolled over (or deferred) in certain circumstances, including:

- a transfer between spouses upon the breakdown of a marriage or relationship; or

- the loss or destruction of the asset.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Companies are subject to a tax rate of 30% on taxable income, except for ‘base rate entities’, which are subject to a reduced tax rate of 25% for the 2020/2021 financial year and future years. Base rate entities are companies:

- which have an aggregate turnover of less than A$50 million; and

- where 80% or less of their assessable income is passive income such as royalties and rent, interest income or a net capital gain.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The taxable base is calculated by classifying the income generated by the company and deducting any related expenses incurred to earn that income.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

A company must lodge an annual company tax return. Generally, the lodgement and payment date for small companies is 28 February. If any prior year returns are outstanding, the due date will be 31 October.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

A company can claim a tax deduction on expenses incurred in carrying on its business, provided that those expenses relate to the earning of the assessable income. A company can claim for deductions if:

- the expense was used for the business; or

- the expense was used for a mix of business and personal use, in which case only the business use may be claimed and there must be records to substantiate the deduction.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

A large component of indirect tax in Australia is goods and services tax (GST). GST applies to any form of supply that is:

- made for consideration in the course or furtherance of an enterprise;

- connected with Australia; and

- provided by an entity that is either registered or required to be registered for GST.

The GST rate in Australia is 10%.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

For all goods and services which are subject to GST, an additional 10% is applied.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

The annual payment date for GST is 31 October of each year as displayed on a business activity statement (BAS). The BAS reports GST, the company’s pay as you go (PAYG) instalments, PAYG withholding tax and other taxes. Some entities must report monthly or quarterly, depending on turnover.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

There are no exemptions or deductions available. GST-free (zero-rated) supplies include:

- exports (of goods and services);

- some food products;

- most medical and health products and services;

- most educational courses;

- childcare;

- religious services;

- water;

- sewerage and drainage services; and

- international transport.

Input taxed (exempt) supplies include:

- financial supplies;

- residential rent and sales of residential premises;

- upon election, long-term accommodation in commercial residential premises; and

- fundraising events conducted by charitable and not-for-profit entities.

In Australia, succession law is primarily governed by state and territory legislation, which regulates how a person's estate is distributed upon death. Each jurisdiction has its own set of laws, but they generally cover similar principles regarding wills, intestacy, and family provision claims.

Key Laws Governing Succession in Australia

| Jurisdiction | Governing Legislation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales (NSW) | Succession Act 2006 (NSW) | Covers wills, intestacy, and family provision. |

| Victoria | Administration and Probate Act 1958 (Vic) | Similar to NSW; includes family provision claims. |

| Queensland | Succession Act 1981 (Qld) | Intestacy rules and regulation of wills. |

| Western Australia (WA) | Administration Act 1903 (WA) | Distribution on intestacy and family provision. |

| South Australia (SA) | Administration and Probate Act 1919 (SA) | Family provision claims and estate administration. |

| Tasmania | Wills Act 2008 (Tas) & Administration and Probate Act 1935 (Tas) | Laws governing the making of wills and estate distribution. |

| Australian Capital Territory (ACT) | Wills Act 1968 (ACT) & Administration and Probate Act 1929 (ACT) | Family provision and intestacy rules. |

| Northern Territory (NT) | Administration and Probate Act 1969 (NT) | Covers wills, intestacy, and family claims. |

Can Succession be Governed by the Laws of Another Jurisdiction?

Yes, under certain circumstances, succession can be governed by foreign laws. However, it depends on the nature of the assets and the deceased's connections to the foreign jurisdiction.

When Foreign Laws May Apply:

The following general rules apply to how certain assets are dealt with depending on the nature of the asset involved.

-

Immovable (Real) Property:

- Governed by the law of the jurisdiction where the property is located.

- Example: A property in California would be subject to California succession laws, even if the owner was an Australian resident.

-

Movable (Personal) Property:

- Generally governed by the law of the deceased's domicile at the time of death.

- Example: Bank accounts, shares, or personal belongings may be governed by Australian succession law if the deceased was domiciled in Australia.

-

Choice of Law in Wills:

- Under private international law, individuals can choose to have their will governed by a particular jurisdiction, but the choice may be limited.

- For example, an Australian resident may create a separate will under US law to govern US assets.

-

International Wills Convention (1973):

- Australia is a signatory to the Convention Providing a Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will 1973 (‘the Convention’), allowing wills to be recognised across other signatory countries. All states and territories in Australia have passed legislation to give effect to the convention.

- The convention seeks to harmonise and simplify proof of formalities for wills that have international characteristics. It does this by setting up a uniform law introducing a new form of will, known as an 'international will', which is recognised as a valid form in all countries that are party to the convention.

- As of 31 March 2025, according to the UNIDROIT.org website (extracted 31 March 2025 - https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/international-will/status/ ), the following countries are signatories to the Convention:

-

State Signature RT / AS EIF D Australia – AS 10.09.2014 10.03.2015 – Belgium 17.05.1974 RT 21.04.1983 21.10.1983 – Bosnia-Herzegovina * – AS 15.08.1994 15.08.1994 – Canada – AS 24.01.1977 – D: Art. XIV Croatia * – AS 18.05.1994 18.05.1994 – Cyprus – AS 19.10.1982 19.04.1983 – Ecuador 26.07.1974 RT 03.04.1979 03.10.1979 D France 29.11.1974 RT 01.06.1994 01.12.1994 – Holy See 02.11.1973 – – – – Iran 27.10.1973 – – – – Italy – AS 16.05.1991 16.11.1991 D: Arts. I, II, III Laos 30.10.1973 – – – – Libya – AS 04.08.1977 09.02.1978 – Niger – AS 19.05.1975 09.02.1978 – Portugal – AS 19.11.1975 09.02.1978 – Russian Federation 17.12.1974 – – – D: Art. XIII Sierra Leone 27.10.1973 – – – – Slovenia – AS 20.08.1992 20.08.1992 – United Kingdom 10.10.1974 – – – – United States of America 27.10.1973 – – – – - Despite Australia being a party signatory to the Convention, it is important to be aware that enforceability of an international Will in foreign jurisdictions depends on local probate processes.

Conflict of Laws — Resolving Jurisdictional Issues

When assets are located in multiple jurisdictions, conflicts may arise. In such cases the following rules determine how property is to be dealt with:

- Lex Situs Rule: Real property follows the law where it is located.

- Domicile Rule: Personal property follows the law of the deceased's domicile.

- Renvoi Doctrine: Australian courts may apply renvoi, meaning they may refer back to the foreign law if the foreign law defers to another jurisdiction.

Summary

- Australian state and territory laws govern wills, intestacy, and family provision claims.

- Immovable property is governed by the jurisdiction where it is located.

- Movable property is governed by the deceased's domicile.

- International Wills and choice of law clauses may provide flexibility.

- Multiple wills can be used to manage assets across jurisdictions

When a deceased person's estate involves connections to multiple jurisdictions (e.g., assets in different countries or residency in one place but property in another),conflict of laws principles determine which jurisdiction's laws apply. In Australia, these conflicts are resolved through private international law, which includes rules on domicile, lex situs, and renvoi.

In Australia, there is no distinction between real and personal property for the purposes of conflicts of law. Rather, there is a distinction between movable and immovable property. Whether a thing is movable or immovable will be decided by the lex situs (ie, the law of the place where the property is situated).

‘Movable property’ includes chattels not attached to land and other assets that are movable, such as bank accounts and shares. ‘Immovable property’ is land and all interest in land such as title deeds and fixtures.

The general rule is that, irrespective of domicile, the law of the lex situs will determine the succession of the property within the lex situs in relation to immovables. However, with regard to movables, the law of the deceased’s domicile at the date of death will apply.

Key Principles for Resolving Conflicts of Laws

- Lex Situs (Law of the Location) — Real (Immovable) Property

-

- Real property (e.g., land, houses) is always governed by the law of the country where the property is located.

- Example:

-

- An Australian resident who owns property in California will have that property governed by California succession laws, regardless of what their Australian will states.

- Domicile — Personal (Movable) Property

-

- Movable property (e.g., cash, shares, personal belongings) is governed by the law of the deceased's domicile at the time of death.

- Domicile is the place a person treats as their permanent home.

- Example:

-

- If a person domiciled in Australia dies, their bank accounts, shares, and personal belongings are distributed under Australian law, even if those assets are located in another country.

- Renvoi Doctrine — Referring Back to Another Jurisdiction

-

- Renvoi is a legal doctrine where a court refers back to the laws of another jurisdiction if that jurisdiction's laws point back to the original jurisdiction.

- Example:

-

- If an Australian court is handling a case regarding US property and US law points back to Australian law, the Australian court may accept the renvoi and apply Australian law.

Choice of Law — Electing Jurisdiction in a Will

- Individuals can choose which jurisdiction’s law should govern their succession for movable assets.

- This is permitted under private international law, but not all jurisdictions recognise it.

- Example:

-

- An Australian resident with assets in the US may specify that Australian law applies to movable assets, but this may not be enforceable if it conflicts with mandatory local laws.

International Conventions Impacting Conflict of Laws

International Wills Convention (1973)

Australia is a signatory to the Convention Providing a Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will 1973 (‘the Convention’), which allows wills executed under this form to be recognised in other signatory countries.

All states and territories in Australia have passed legislation to give effect to the convention.

Despite Australia being a party signatory to the Convention, it is important to be aware that enforceability of an international Will in foreign jurisdictions depends on local probate processes.

Dealing with Conflicting Jurisdictions in Practice

- Multiple Wills: To avoid conflicts, individuals often create separate wills for each jurisdiction where they hold assets.

- Obtaining a Reseal: If probate is granted in Australia, a reseal of probate may be needed for assets in other jurisdictions, depending on whether that jurisdiction recognises Australian grants.

- Legal Advice in Multiple Jurisdictions: Executors may need to seek legal advice in each jurisdiction where the deceased held assets.

Summary

| Conflict Rule | Applies To | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Lex Situs (Location) | Real (immovable) property | Governed by the law where the property is located. |

| Domicile | Personal (movable) property | Governed by the deceased's last domicile. |

| Renvoi | When laws refer back | Court may accept or reject the referral. |

| Choice of Law | Electing a jurisdiction | Permitted for movable property, but not always enforceable. |

| International Wills Convention | Form of will | Ensures recognition of wills but does not override local probate laws. |

Australia does not have rules of forced heirship, unlike many civil law jurisdictions where a portion of the deceased's estate must go to certain heirs (such as children or spouses). Instead, Australia follows the principle of testamentary freedom, meaning individuals are generally free to distribute their assets as they wish through a will.

However, this freedom is not absolute. Australia's succession laws (as enacted in each of the states and territories) include provisions for family provision claims, allowing certain eligible persons to challenge a will and/or the laws of intestacy if they believe they have been inadequately provided for.

Testamentary Freedom vs. Family Provision Claims

Testamentary freedom refers to the right of individuals to distribute their assets as they wish through their will. However, this principle is subject to legal challenge under certain circumstances. Family provision laws allow eligible persons to contest a will if they believe they have not been adequately provided for. This right to challenge is limited, as only individuals who meet specific eligibility criteria can bring a claim under the relevant legislation.

Family Provision Claims:

- If an eligible person is left out of the will or receives insufficient provision, they can apply to the court for a family provision order.

- The court can alter the distribution of the estate if it deems the provision inadequate.

Who Can Make a Family Provision Claim - eligibility?

The eligibility criteria vary slightly across states and territories, but common categories include:

| Eligible Claimants | Definition |

|---|---|

| Spouse | Legal spouse or de facto partner. |

| Former Spouse | In some jurisdictions (e.g., NSW and Victoria (subject to exceptions)), a former spouse may claim. |

| Children | Biological, adopted, or stepchildren. |

| Grandchildren | In limited circumstances (if they were dependent on the deceased). |

| Dependents | Any person who was wholly or partly dependent on the deceased. |

| Close Personal Relationship (NSW) | Two adults living together in a close personal relationship, often non-romantic. |

Factors the Court Considers

As outlined above, each of the states and territories have enacted legislation which outlines the eligibility and factors the court must take into account when determining a family provision claim. When determining whether to make an order or further provision, the court considers factors such as:

- Size and nature of the estate.

- Financial needs and resources of the claimant.

- Relationship between the claimant and the deceased.

- Health, age, and earning capacity of the claimant.

- Any moral obligation the deceased may have had.

- Conduct of the claimant (in some cases).

Time Limits for Making a Claim

Time limits for lodging a family provision claim vary by state:

| Jurisdiction | Time Limit to File a Claim |

|---|---|

| NSW | 12 months from the date of death. |

| Victoria | 6 months from the grant of probate. |

| Queensland | 9 months from the date of death. |

| WA | 6 months from the grant of probate. |

| SA | 6 months from the grant of probate. |

| Tasmania | 3 months from the grant of probate. |

| ACT | 6 months from the grant of probate. |

| NT | 12 months from the grant of probate. |

Key Differences from Forced Heirship

| Feature | Forced Heirship (Civil Law) | Australia (Common Law) |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory Distribution | Yes — Certain heirs have a guaranteed share. | No — Complete testamentary freedom (subject to family provision). |

| Eligible Heirs | Spouse, children, descendants. | Spouse, children, dependents, others (varies by state). |

| Automatic Enforcement | Mandatory — Heirs automatically receive their share. | Not automatic — Requires a court application. |

| Challenge Grounds | Not applicable — Shares are fixed by law. | Inadequate provision or moral obligation. |

| Asset Scope | Often includes entire estate. | May exclude non-estate assets (e.g., jointly owned property, superannuation). |

Summary

- No forced heirship exists in Australia.

- Individuals have the freedom to distribute assets as they wish.

- Family provision claims offer a safeguard for eligible dependents who might have otherwise missed out on the opportunity to challenge the idea of testamentary freedom.

- The court assesses various personal and financial factors before altering a will.

Whilst Australia has no force heirship rules, a set of laws enacted in the relevant legislation each of the Australian states and territories known as ‘laws of intestacy’ apply when a person dies intestate (without a valid will) in Australia. In such cases, the estate is distributed according to the intestacy rules set out in the relevant state or territory legislation governing succession in those jurisdictions.

As succession laws are governed not at federal level, but rather, at each of the state and territory levels, each jurisdiction in Australia has its own set of rules for how an intestate estate is distributed. Despite this, the basic principles are similar across the country.

For example:

- New South Wales (NSW): Governed by the Succession Act 2006 (NSW), which provides specific formulas for dividing the estate between a surviving spouse and children.

- Victoria: Governed by the Administration and Probate Act 1958 (Vic).

- Queensland: Governed by the Succession Act 1981 (Qld), with a different formula for spousal entitlements.

- Western Australia: Governed by the Administration Act 1903 (WA), where a spouse might receive a larger share if there are no children.

Intestacy Rules in Australia

When someone dies intestate, the estate is divided according to a prescribed order of priority, based on family relationships. The key steps include:

Order of Priority for Distribution

| Relationship | Distribution Rules |

|---|---|

| Spouse and Children | The estate is generally split between the surviving spouse and the children. The spouse may receive a fixed sum (which varies by jurisdiction) and the rest is divided among the children. In some cases, the spouse may inherit the entire estate if the deceased had no children or if the children are the children of the same relationship between the deceased and spouse. |

| Spouse (No Children) | If the deceased has no children, the surviving spouse typically receives the entire estate. |

| Children (No Spouse) | If there is no surviving spouse, the estate is divided equally among the children. |

| Parents (No Spouse/Children) | If there are no surviving spouse or children, the estate is distributed equally between the deceased’s parents (if they are alive). |

| Siblings (No Spouse, Children, or Parents) | If no spouse, children, or parents are alive, the estate is divided among the deceased's siblings (or their descendants, such as nieces and nephews). |

| Other Relatives (No Immediate Family) | If there are no immediate family members, distant relatives (such as grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins) may inherit according to the laws of the state or territory. If no relatives can be found, the estate may ultimately go to the state. |

In the absence of a will, an administrator (usually the surviving spouse or another close family member) is appointed by the court to administer the estate. This is typically done by obtaining letters of administration, which grant the authority to distribute the estate according to the intestacy rules.

Even if the deceased has died intestate, family provision claims can still be made. A family provision claim allows eligible persons to challenge the distribution of the estate if they feel that they have not been adequately provided for, regardless of whether there is a will or if the estate is being distributed according to the intestacy rules.

To prevent clogging up the courts with baseless claims, legislation has been enacted in each of the states and territories which specifies who may make such claims (known as eligible persons).

Generally, these include:

- Spouse, including de facto partners (and in some jurisdictions, former spouses).

- Children, including adopted children, stepchildren, and sometimes grandchildren.

- Dependents (e.g., someone who was financially dependent on the deceased).

Time Limits:

Family provision claims usually have a time limit (e.g., 12 months in NSW) from the date of death or the date of the grant of letters of administration (e.g., 6 months in Victoria). The court will consider the claimant's needs and the size of the estate before making an order to alter the intestate distribution.

Impact of Intestacy on Property and Assets

- Real Property (Land and Houses): The rules of intestacy apply to all types of property, including real estate. The ownership and distribution of property depend on the relationships of the surviving family members.

- Joint Assets: Jointly owned property, such as bank accounts or real estate with a spouse, may pass to the surviving joint owner automatically, as it is typically held in joint tenancy. This may reduce the size of the intestate estate that must be divided under the intestacy rules.

- Superannuation: Superannuation death benefits may be handled separately from the estate. The superannuation trustee may decide to pay the benefits to the deceased’s dependents, regardless of the intestacy rules.

Summary: How Intestacy Rules Work in Australia

- When a person dies intestate, the estate is distributed according to state or territory intestacy laws.

-

The order of succession typically prioritises:

- Spouse and children.

- If no spouse or children, parents, siblings, or other relatives.

- Family provision claims can still be made if an eligible person feels inadequately provided for, even under intestacy.

- Intestacy affects estate administration — an administrator is appointed to manage the estate and follow the laws of intestacy.

- Property distribution may also be influenced by joint ownership or superannuation regulations.

In Australia, wills and estates are governed by state and territory legislation, meaning the relevant laws differ depending on the jurisdiction in which the deceased was domiciled. The key legislation includes:

- Victoria – Wills Act 1997 (Vic) and Administration and Probate Act 1958 (Vic)

- New South Wales – Succession Act 2006 (NSW)

- Queensland – Succession Act 1981 (Qld)

- South Australia – Wills Act 1936 (SA) and Inheritance (Family Provision) Act 1972 (SA)

- Western Australia – Wills Act 1970 (WA) and Family Provision Act 1972 (WA)

- Tasmania – Wills Act 2008 (Tas) and Testator’s Family Maintenance Act 1912 (Tas)

- Northern Territory – Wills Act 2000 (NT) and Family Provision Act 1970 (NT)

- Australian Capital Territory – Wills Act 1968 (ACT) and Family Provision Act 1969 (ACT)

Each jurisdiction has its own rules regarding the formal requirements for making a valid will, estate administration, and provisions for contesting a will.

A will can be governed by the laws of another jurisdiction in certain circumstances. The key considerations include:

- Domicile of the Deceased: Generally, the laws of the state or territory where the deceased was domiciled at the time of death will govern the administration of their estate.

- Location of Assets: If the deceased held assets in multiple jurisdictions (including overseas), different laws may apply to the distribution of those assets.

- Choice of Law Clause: In some cases, a will may specify that it is to be governed by the laws of a particular jurisdiction, though this may not always override the relevant succession laws where the assets are located.

- International Considerations: If a person has assets in a foreign country, that country’s laws may impact the administration and taxation of the estate. Some countries do not recognise Australian wills, requiring a separate will in that jurisdiction.

When a deceased person's estate involves connections to multiple jurisdictions (e.g., assets in different countries or residency in one place but property in another),conflict of laws principles determine which jurisdiction's laws apply. In Australia, these conflicts are resolved through private international law, which includes rules on domicile, lex situs, and renvoi.

In Australia, there is no distinction between real and personal property for the purposes of conflicts of law. Rather, there is a distinction between movable and immovable property. Whether a thing is movable or immovable will be decided by the lex situs (ie, the law of the place where the property is situated).

‘Movable property’ includes chattels not attached to land and other assets that are movable, such as bank accounts and shares. ‘Immovable property’ is land and all interest in land such as title deeds and fixtures.

The general rule is that, irrespective of domicile, the law of the lex situs will determine the succession of the property within the lex situs in relation to immovables. However, with regard to movables, the law of the deceased’s domicile at the date of death will apply.

Key Principles for Resolving Conflicts of Laws

- Lex Situs (Law of the Location) — Real (Immovable) Property

-

- Real property (e.g., land, houses) is always governed by the law of the country where the property is located.

- Example:

-

- An Australian resident who owns property in California will have that property governed by California succession laws, regardless of what their Australian will states.

- Domicile — Personal (Movable) Property:

-

- Movable property (e.g., cash, shares, personal belongings) is governed by the law of the deceased's domicile at the time of death.

- Domicile is the place a person treats as their permanent home.

- Example:

-

- If a person domiciled in Australia dies, their bank accounts, shares, and personal belongings are distributed under Australian law, even if those assets are located in another country.

- Renvoi Doctrine — Referring Back to Another Jurisdiction

-

- Renvoi is a legal doctrine where a court refers back to the laws of another jurisdiction if that jurisdiction's laws point back to the original jurisdiction.

- Example:

-

- If an Australian court is handling a case regarding US property and US law points back to Australian law, the Australian court may accept the renvoi and apply Australian law.

Yes, foreign wills can be recognised in Australia under certain circumstances. The process for recognising a foreign will depends on various factors, including whether the will meets Australian legal requirements and the jurisdiction where the will was made.

Key Considerations for Recognition

- Validity Under Foreign Law – A will made in another jurisdiction may be recognised if it is valid under the laws of the country where it was executed.

- Recognition Under Australian Law – The will must also comply with Australian succession laws, particularly regarding execution, testamentary capacity, and undue influence.

- Conflict of Laws Principles – If a deceased person had assets in Australia and another country, different legal systems may govern different parts of the estate (e.g., immovable property such as land is usually governed by the law of the country where it is located).

Process for Recognising a Foreign Will in Australia

- Resealing of a Foreign Grant – If probate has been granted in a foreign jurisdiction, an application can be made to the Supreme Court of an Australian state or territory to "reseal" the foreign grant of probate. This process applies to only certain recognised jurisdictions, including the UK, New Zealand, and some other Commonwealth countries.

- Probate as a Foreign Will – If the will has not been granted probate overseas, an application for probate can be made in Australia as if the will were an Australian will. The applicant must provide evidence that the will is valid under the law of the place where it was executed.

- Intestate Succession – If a foreign will is not recognised and no valid Australian will exists, Australian intestacy laws may apply to assets located in Australia.

Testamentary freedom is balanced against the testator’s moral responsibility to certain eligible persons such as spouses or children, to make proper provision for their adequate maintenance and support. If a testator has failed to make adequate provision for such persons, the will may be subject to challenge.

The courts also consider whether the eligible person has a need for provision or further provision from the estate.

In Australia, each state and territory has legislation governing the formal requirements for a valid will. However, the fundamental requirements are generally consistent across jurisdictions.

Key Formal Requirements for a Valid Will:

-

The Will Must Be in Writing

- The will must be written, either handwritten, typed, or printed. Oral wills are not legally valid (although they may still be admitted to probate in some circumstances as an informal will).

-

The Testator Must Have Testamentary Capacity

- The testator (the person making the will) must:

-

- Be at least 18 years old (exceptions apply for minors in limited circumstances).

- Be of sound mind, memory, and understanding at the time of making the will.

- Understand the nature and effect of the will, including the extent of their estate and the claims of potential beneficiaries.

- Intend the document to be their Will.

-

The Will Must Be Signed by the Testator

- The testator must sign the will at the end of the document.

- If the testator cannot physically sign, they may direct someone to sign on their behalf in their presence.

-

The Will Must Be Witnessed

- The testator’s signature must be witnessed by at least two people who are both:

-

- Present at the same time when the testator signs.

- Over 18 years old.

- Witnesses should not be beneficiaries (or the spouses of beneficiaries), as this may affect their entitlement under the will.

-

The Will Must Be Made Voluntarily

- The will must be made without undue influence, coercion, or fraud.

Exceptions & Special Circumstances:

- Holographic Wills: Some jurisdictions (e.g., NSW) may accept a will that is entirely handwritten by the testator, even if it does not meet all formal witnessing requirements.

- Informal Wills: Courts may recognise an informal will (one that does not strictly comply with legislative requirements) if clear intent can be proven.

- International Wills: A will made overseas may be recognised in Australia if it meets Australian legal standards or complies with the Convention Providing a Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will 1973.

When drafting a will in Australia, a number of best practices can be adopted to mitigate the risk of a a successful challenge to the Will and can help ensure that the will is legally valid.

The following key considerations should be observed:

1. Compliance with Legal Formalities

- Ensure the will is in writing (handwritten, typed, or printed).

- The testator must be at least 18 years old (unless an exception applies).

- The will must be signed by the testator in the presence of two witnesses, who must also sign the will.

- Witnesses should not be beneficiaries or the spouse of a beneficiary.

2. Confirm Testamentary Capacity

- The testator must be of sound mind, memory, and understanding at the time of making the will.

- They must comprehend:

-

- The nature and effect of the will.

- The extent of their estate.

- The claims of potential beneficiaries.

- If there is any doubt about the testator’s capacity (e.g., due to age, illness, or cognitive decline), obtaining a medical certificate or having a solicitor assess and record their capacity is advisable.

3. Avoiding Undue Influence & Fraud

- The testator must make the will voluntarily, without coercion or pressure from others.

- If undue influence is suspected (e.g., if a vulnerable person changes their will significantly in favor of one party), independent legal advice should be sought.

4. Clarity and Precision in Language

- Use clear and unambiguous language to avoid misinterpretation.

- Specify exactly how assets should be distributed and identify beneficiaries by full name and relationship to the testator. This will assist the executor/administrator to identify and locate the beneficiaries when administering your estate.

- Include contingency plans, such as what happens if a beneficiary predeceases the testator so as to prevent the risk of the gift failing.

5. Appointment of Executors and Trustees

- Name a trusted executor to administer the estate and carry out the testator’s wishes.

- If assets are held in trust (e.g., for minor children), appoint a trustee to manage them.

- Consider naming a backup executor in case the primary executor is unable or unwilling to act.

6. Providing for Dependents & Avoiding Family Provision Claims

- Ensure adequate provision is made for spouses, children, and other dependents to minimize the risk of family provision claims.

- If intentionally excluding a close family member, record the reason in a separate document (or include a clause in the will) to help defend against potential claims.

7. Reviewing and Updating the Will

- Regularly review the will, especially after major life events such as:

-

- Marriage, divorce, or separation.

- Birth or death of a family member.

- Acquisition or disposal of significant assets.

- A new will should be drafted if significant changes are required, rather than making excessive amendments.

8. Storing the Will Safely

- Keep the original will in a secure location, such as:

-

- With a solicitor.

- In a safe deposit box.

- With the Supreme Court’s will registry (where applicable).

- Inform executors and key family members where the original will is stored.

Finally, obtaining legal advice. Meeting with a legal practitioner specialising in the area of Wills and estates will enable the testator to obtain legal advice regarding their testamentary wishes specific to their circumstances. Having this legal advice prior to making a will may assist to mitigate the risk of disgruntled beneficiaries and legal challenges to the will.

In Australia, a will cannot be amended after the death of the testator. However, there are certain circumstances where modifications or alterations may be possible under Australian law:

- Rectification of a Will: Courts in various Australian states and territories have the power to rectify a will if it does not reflect the testator’s true intentions due to clerical error or misunderstanding of instructions. Applications for rectification typically need to be made within a certain timeframe after probate is granted (e.g., six months in some jurisdictions).

- Informal Wills: If a document does not meet the formal requirements of a valid will but was intended to function as one (or as an amendment to an existing will), courts may recognise it as a will under dispensing provisions in the relevant state or territory legislation.

- Family Provision Claims: If a will fails to provide adequate provision for an eligible person (such as a spouse, child, or dependent), they may apply to the Supreme Court in their state or territory for a family provision order. This does not amend the will itself but can alter how the estate is distributed.

- Deeds of Family Arrangement: Beneficiaries can mutually agree to vary the distribution of an estate through a Deed of Family Arrangement, provided all affected parties (including any legal representatives for minors or incapacitated individuals) consent.

When considering whether to, in effect, amend a will (whether by consent or family provision claim), it is important to consider the impacts of the amendment on the beneficiaries. These may include triggering taxes, where tax may otherwise not have been payable, or welfare gifting provisions. We recommend that the executor and beneficiaries intending to enter into a deed of family arrangement obtain independent legal advice before agreeing to any proposed altered distribution.

Each state and territory has its own legislation enabling eligible applicants to make a claim for provision or further provision from a deceased estate. Generally, for an application to succeed, the following elements must be satisfied.

Eligible applicant: The following persons are generally considered to be eligible applicants Australia wide:

- a spouse or domestic partner of the deceased at time of death;

- a child, including a stepchild, of the deceased; and

- a person who was wholly or partially dependent on the deceased, to the extent the deceased had a moral obligation to provide for that person in the will.

Relevant considerations: A claim must generally be made within six months of grant of representation being issued by the court or 12 months of the date of death, depending on the state or territory in which the deceased was domiciled. When assessing the validity of a claim, the court will consider various factors, including:

- the terms of the deceased’s will (if any);

- evidence of why the deceased drafted the will in a certain way; and

- any evidence as to the deceased’s intentions in relation to provision for the applicant.

The court may also consider other factors, such as:

- the size of the estate;

- the relationship between the deceased and the applicant;

- the applicant’s personal and financial circumstances;

- the circumstances of the other beneficiaries; and

- any other circumstances that the court sees fit.

Australian courts place a strong focus on whether the deceased had a moral obligation and the adequacy of any provision made. They also consider whether the applicant has a need for provision from the estate.

When a person dies without a valid will (intestate), their estate is distributed according to the intestacy laws of the state or territory where they resided. While the rules vary slightly across jurisdictions, they generally prioritise spouses, children, and other close relatives.

Each Australian state and territory has its own intestacy laws governing how an estate is distributed when a person dies without a valid will:

- Victoria – Administration and Probate Act 1958 (Vic)

- New South Wales – Succession Act 2006 (NSW)

- Queensland – Succession Act 1981 (Qld)

- South Australia – Administration and Probate Act 1919 (SA)

- Western Australia – Administration Act 1903 (WA)

- Tasmania – Intestacy Act 2010 (Tas)

- Australian Capital Territory – Administration and Probate Act 1929 (ACT)

- Northern Territory – Administration and Probate Act 1969 (NT)

These laws set out the hierarchy of beneficiaries and how an estate is distributed in the absence of a will.

Who Inherits Under Intestacy Laws?

- Spouse and No Children → The spouse inherits the entire estate.

- Spouse and Children (from that spouse) → The spouse inherits the entire estate.

- Spouse and Children (from a different relationship) → The estate is usually split between the spouse and children.

- No Spouse, but Children → The children inherit the estate in equal shares.

- No Spouse or Children → The estate passes to parents, then siblings, then more distant relatives (grandparents, aunts/uncles, cousins).