- within Environment topic(s)

- in United States

- within Environment, Transport, Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

Preamble

The space industry, particularly the provision of space-based data and space services is increasingly important for both the Union's economy and the daily life of citizens. However, the EU currently faces a fragmented space market and regulatory environment due to varying national laws, complicating cross-border space operations. To counteract this legal heterogeneity, the European Commission has drafted the legislative proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the safety, resilience and sustainability of space activities in the Union (the EU Space Act, "pEUSA" / "Regulation"). The pEUSA aims to harmonise regulations to create a unified internal market. By focusing on safety, resilience, and sustainability, it seeks to enhance legal certainty and boost competitiveness for Europe's space industry globally.

This article examines the question of the pEUSA's material and territorial scope, with a particular focus on its internal inconsistencies and ambiguities.

Material scope

At a first glance, Art. 1 and 21 clearly define the pEUSA's scope.

- Art. 1 states – in summary – that the regulation aims to ensure a high level of safety, resilience and environmental sustainability for space services and space-based data. It therefore establishes rules for the authorisation, registration and supervision of space activities conducted by space services providers established in the Union or third countries.

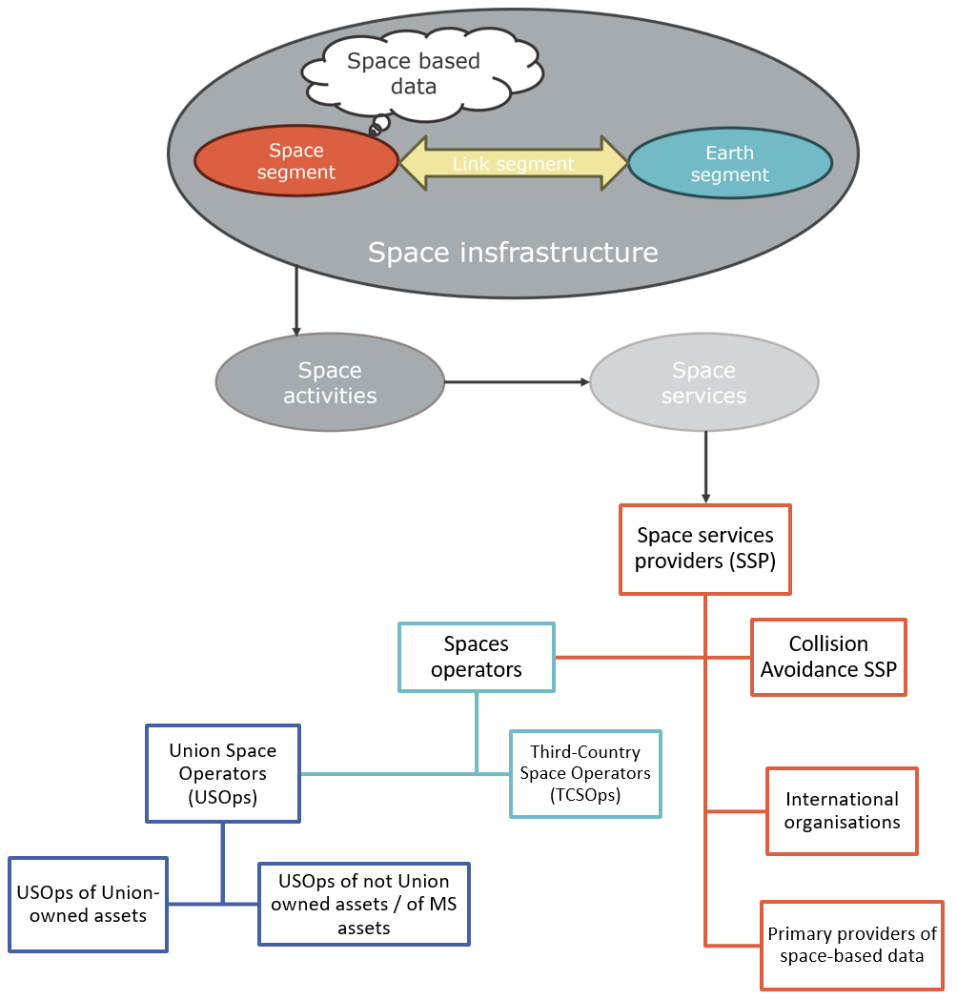

- Art. 2(1) then continues defining the relevant space services providers: "This Regulation applies to the following space services providers: (a) space operators; (b) collision avoidance space services providers; (c) primary providers of space-based data; (d) international organisations2."

Upon closer inspection, the clarity and unambiguity of these two provisions diminish. Firstly, it is imperative to consider the exact definitions of the terms (e.g. space services provider) used in Art. 1 and 2; the definitions are listed in Art. 5 and outlined below. Furthermore, to definitively ascertain the scope of application, it is necessary to undertake a comprehensive analysis of further provisions, and their terminology. However, many of these terms are difficult to distinguish, causing confusion rather than clarity. This makes it challenging for an entity to conclusively determine if the pEUSA applies to them.

A. Space Activities and Space Services

The first two key terms are space activities and space services. Art. 1 states that authorising, registering and supervising space activities is necessary to ensure a high level of safety, resilience and sustainability for space services. Articles 5(13) and 5(14) pEUSA define these terms.

- Space activities are defined as "set of operations when carrying out activities in outer space" such as the operation and control of space objects, including related ground-based operations like maintaining launch sites or providing launch attempts, which use space infrastructure (Article 5(13)). The list provided in this Article is not exhaustive.

- Space services, in contrast, are defined as "any of the following services" (i.e. an exhaustive list), with the list containing services such as operation and control of a space object, provision of launch services, in-space services, collision avoidance space services and any of the services provided by a primary provider of space-based data (Art. 15(14)).

Although the lists of space activities and space services overlap, the regulation does not clearly distinguish between these two concepts or define their relationship. However, the wording suggests that space services constitute a sub-sector of the broader space activities.

B. Space Services Provider and Space Operator

The entities providing space services are called space services providers (Art. 5(15)) ("SSP"). The pEUSA differentiates between Union based SSP and third country based SSP, with both of them falling within the scope of application. Art. 2(1) lists the specific SSP to which the pEUSA applies. These are: a) space operators, b) collision avoidance ("CA") space services providers, c) primary providers of space-based data ("PPD"), and d) international organisations ("IO"). Four points warrant clarification:

- SSP are defined in art. 5(15) as "providers of space services covered by this Regulation." The provision does not clarify the meaning of "covered by this Regulation." Consequently, it is unclear whether this phrase refers to 1) the space services listed in Art. 5(14), 2) the geographical scope of the pEUSA, or 3) the SSP listed in Art. 2, which would result in a circular definition. This ambiguity obscures the definition of SSP. The wording of 5(15) suggests that "covered by this Regulation" refers to the space services listed in Art. 5(14).

- Since Art. 5(16) defines space operators as entities carrying out "at least one of the following space services" and the list contained in Art. 5(16) is not identical to the enumeration in Art. 5(14), it is to be concluded, that space operators are a specific subgroup of SSP. The same applies to CA space services providers and primary providers of space-based data; they are also subgroups of SSP.

- According to Art. 2, the pEUSA applies only to the SSP listed therein. Consequently, some SSP fall outside its scope, even if they provide space services or conduct space activities, because they do not qualify as space operators, do not provide CA services, and are not PPD.

- Entities that only conduct space activities, but do not provide space services, fall outside the scope of the pEUSA, since they do not qualify as SSP and therefore fall outside the scope of Art. 2(1). This scenario is probable, particularly because the pEUSA lists space services exhaustively, but not space activities.

As an interim conclusion, it can be stated that the scope of the pEUSA is linked, on the one hand, to the status of a company as a "space services provider", even though the definition of this term in Art. 5(15) is not entirely unambiguous.

Territorial Scope

Recitals 23-25 establish that the pEUSA's applies to the provision of space-based data or space services within the Union. Consequently, the pEUSA applies to SSP offering such data or services in the Union, irrespective of their place of establishment, thereby including third country-based SSP.

A key ambiguity arises for Union-based space operators (a sub-category of SSP) that conduct space activities or offer space services exclusively outside the Union. On the one hand, Art. 2 and 6 appear to establish extraterritorial scope over these Union-based operators based on their establishment, irrespective of where they provide the services. For example, Art. 6 states that Union-based space operators "shall not provide space services unless [...]," implying the service's location is irrelevant.

On the other hand, Recital 23 states that "[...] the rules for all space services providers within the scope of this Regulation, including Union space operators, should apply to the extent space-based data and space services are provided in the Union." This strongly suggests that the pEUSA does not cover the provision of space services or space-based data outside the Union, even if the SSP is based in the Union.

Therefore, as Recital 23 clarifies, the pEUSA's applicability is ultimately limited to the provision of space services and space-based data within the Union. This means the service location, not the operator's establishment is the controlling factor.

Authorisation, registration and certification

Title II of the Regulation establishes the rules for authorising and registering "space activities" (wording of Title II). To provide "space services" (wording of Art. 6 as first provision under Title II) and data, space operators must comply with the proposed pEUSA. Compliant space operators can or must then register in the Union Register of Space Objects ("URSO"). The compliance assessment varies depending on the entity and is not further outlined or analysed in this article.

The above-mentioned authorisation provisions are somewhat unclear. As an abstract legislative act, the pEUSA employs similar yet inconsistent terminology (e.g. space activities vs. space services; authorisation only for space operators), which creates unnecessary confusion. The specific ambiguities are discussed below. It is to be noted, that the pEUSA also distinguishes between the authorisation and registration process for Union based operators and third country-based operators. The following sections will discuss these specific ambiguities and the two subgroups separately.

A. Union-Based Space Operators

Union-based space operators demonstrate compliance through an authorisation from their Member State of establishment, which confirms their clearance to operate and conduct space activities (Art. 6(1)). Several points warrant attention.

First, Art. 6 applies exclusively to Union space operators. Consequently, other Union-based SSP under the scope of pEUSA, such as collision avoidance (CA) space services providers and primary providers of space-based data (Art. 2(1)), do not require this authorisation. Their specific requirements are listed in Art. 25, 26 and 27 and will not be further analysed here.

Furthermore, it is confusing that according to Art. 6, space operators need an authorisation for space activities to provide space services ("Union space operators shall not provide space services unless they have obtained in a Member state an authorisation to carry out space activities [...]"). Linking the authorisation to the broader definition of space activities to legitimise the more narrowly defined space services seems impractical and illogical.

For Union based space operators intending to operate or launch Union-owned assets, the Commission (not the Member State) issues the authorisation based on a technical assessment proposal from the European Union Agency for the Space Programme ("Agency") (Art. 11(1); explanatory memorandum, p. 10). The Agency conducts the assessment and recommends to the Commission either to issue or refuse the authorisation (Art. 12(1)).

Following the authorisation (issued by a Member State or the Agency), Union based space operators are registered in the URSO (Art. 24(1)(a)). Upon registration, the Agency issues and delivers an e-certificate (Art. 25). Another ambiguity arises concerning the URSO registration: although URSO stands for "Union Register of Space Objects," some provisions in the pEUSA (e.g. wording of Art. 24), respectively mention the registration of the SSP itself, not the space objects. Conversely, the pEUSA also stipulates that space-based data can only be provided if generated by a space object registered in the URSO (Art. 27(1)).

B. Third Country-Based Space Operators

To provide space services, third country-based space operators must obtain a registration in the URSO as well as an e-certificate under Art. 14.

Similar to Art. 6, Art. 14(1) limits this licensing regime to "third country space operators". This limitation seems unintended, as it means that third country-based SSP not qualifying as space operators fall outside the scope of Art. 14(1), even though all third country-based SSP would have to undergo an examination and subsequent registration.

Instead of harmonising regulations for the internal space market, the act creates legal uncertainty, making it difficult for affected entities to determine their obligations.

C. Primary Providers of Space-Based Data

PPD are subject to a more lenient regime than space operators, as they are conveniently not bound by their substantive rules. Consequently, PPD do not undergo the technical authorisation for URSO registration; instead, the system generates their record via a separate, less demanding administrative list (Art. 27). PPD provide space-based data within the Union, positioning themselves as intermediaries between space operators and users (Recital 22). Their sole requirement is to ensure data originates from a space object registered in URSO (Art. 27(1)), which implies the object is operated by a registered SSP. This provision presumably applies to both Union-based and third-country PPD, though the text lacks definitive clarity on its enforcement, particularly concerning the latter.

Conclusion

Introducing a harmonised framework for space activities, services and data across the Union represents a significant and positive step, however the draft still exhibits a number of ambiguities. Key terms such as "space activities" and "space services" are not clearly distinguished, and the scope of application for different entities is defined in a way that can appear circular and overlapping. The provisions on authorisation and registration would also benefit from greater precision, particularly regarding their application to the various types of SSP, operators, services and activities covered. As a result, rather than offering the desired level of legal certainty, the current draft can create uncertainty for entities trying to understand their obligations, which may limit its effectiveness in fostering a clear internal market for space services.

Illustration: The correlation between space infrastructure, space activities and space services

Footnotes

1 All provisions listed refer to the pEUSA, unless defined otherwise.

2 This article excludes international organisations and does not address the subject of their involvement.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.