- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

China's data protection laws are in a period of rapid development and change. On 20 August 2021, the Standing Committee of China's National People's Congress promulgated the long-waiting Personal Information Protection Law ("PIPL"), which will come into effect on 1 November. The PIPL, together with the Guarding State Secrets Law (2010), the Cybersecurity Law (2017), the Encryption Law (2020), and the Data Security Law (2021), have formed the legal framework of data protection and cybersecurity in China.

As the most influential legislation in the field of data protection, EU's General Data Protection Regulation ("GDPR") has many techniques that has been borrowed by China in legislating the PIPL. Nevertheless, there are still many differences between the GDPR and the PIPL because of the different visions for individual's rights and national security. In this article, we will highlight the key points in the PIPL by comparison with the GDPR.

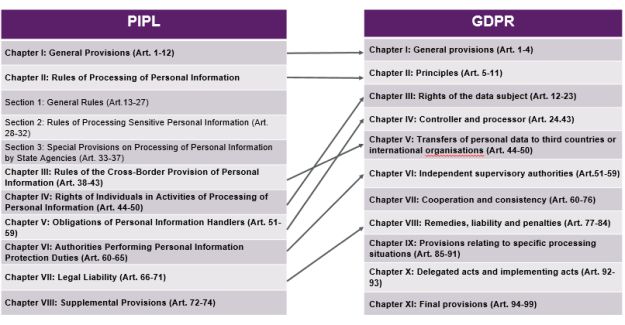

I. The Structure of the PIPL

The PIPL is composed of 8 chapters containing 74 articles, and we can find the corresponding chapter in GDPR for most of them. But the specific provisions in the PIPL maintain unique features to reflect local regulatory and business needs at the same time.

The entity that bears most personal information protection obligations in the PIPL is "personal information handler". The concept of such personal information handler can be understood as the same as the personal data controller used in the GDPR. Article 73 of the PIPL defines such a "personal information handler" as organizations and individuals that independently determine the processing purposes and means in personal information processing activities. On the other hand, the concept of personal data processor in GDPR is translated into "entrusted party" in the PIPL.

According to the PIPL, a handler shall comply with a series of processing principles and adopt organizational, technical, and other measures to protect personal information. As required by the PIPL, the handler should also abide by specific rules when it is engaging with a joint handler, a processor (namely "entrusted party" in the PIPL language), or other recipients.

In terms of legal basis, the PIPL takes an approach similar to the GDPR, which provides multiple legal bases for processing personal information in addition to consent, including necessity for the conclusion or performance of contract (including employment contract), performance of statutory duties or obligation, etc. Compared with the GDPR, the PIPL does not recognize "legitimate interests pursued by the controller" as a legal basis for personal information processing.

With respect to personal information rights of the individuals, the PIPL mostly aligns with the GDPR, but it set restrictions on the right to data portability. Article 45 of the PIPL provides that personal information handlers shall provide a channel for an individual to transfer his/her personal information only when conditions prescribed by the competent department are met. This provision may be intended to prevent tech companies from overburdens.

| Personal Information Rights | GDPR | PIPL |

| Right to information | 🗸 | 🗸 |

| Right to access/copy | 🗸 | 🗸 |

| Right to correction/rectification | 🗸 | 🗸 |

| Right to erasure | 🗸 | 🗸 |

| Right to object/restrict processing | 🗸 | 🗸 |

| Right to data portability | 🗸 | 🗸 |

| Right regarding automated decision making | 🗸 | 🗸 |

II. Cross-Border Data Transfer

The PIPL has some elements in common with the GDPR in terms of the cross-border transfer of personal information. But it also has some additional requirements as the PIPL is characterized by its distinct flavor of national security.

Unlike the GDPR, the PIPL has not adopted an adequacy decision mechanism, and the transfer of personal information shall meet certain requirements regardless of the location of the recipient of the personal information.

According to the PIPL, in general, transferring personal information outside the territory of China shall meet three necessary conditions, namely (1) obtaining the personal information subject's separate and informed consent; (2) conducting personal information protection impact assessment and making record; and (3) adopting one of the measures set forth in the PIPL to ensure that adequate safeguards would be provided for the transfer.

The measures for adequate safeguards provided by the PIPL include: (1) passing a security assessment (applicable on certain types of handlers (discussed below)); (2) undergoing personal information protection certification; (3) concluding a standard contract; and (4) meeting other conditions provided in laws or administrative regulations or provided by the Cyberspace Administration of China ("CAC").

It is reported that CAC has begun drafting the standard contract specifying the rights and obligations of both parties in cross-border data transfer. Besides, the PIPL does not provide for a mechanism akin to the Binding Corporate Rules.

In addition, the PIPL has set special requirements regarding localization and security assessment out of national security concerns. Under the PIPL, the critical information infrastructure operators ("CIIOs") and personal information handlers handling personal information reaching quantity threshold provided by the CAC can only transfer the personal information overseas after a security assessment organized by the CAC is passed, unless otherwise provided for in laws, administrative regulations and CAC provisions.

III. Enforcement and Litigation

i. Penalty

If a handler violates the PIPL, the enforcement authority may order it to rectify, issue warnings, confiscate illegal income, suspend its services or other business activities, revoke its business license, and of course, issue a fine. The GDPR sets a maximum fine of EUR 20 million or 4% of annual global turnover – whichever is greater – for infringements, while the fine under the PIPL can be up to RMB 50 million (equivalent to approx. USD 7.73 million) or 5% of the organization's annual turnover. But the PIPL has not clarified whether the turnover refers to (1) the worldwide turnover or is limited to the turnover generated within Mainland China, and (2) the group turnover or only the turnover of the undertaking violating the law.

ii. Enforcement authorities

Articles 51-59 of the GDPR require that each EU Member State shall designate an independent, public authority to be responsible for monitoring the application of GDPR, known as a data protection authority ("DPA").

Nevertheless, China does not have a unified law enforcement authority in the area of data protection (and cybersecurity). The PIPL has authorized three kinds of enforcement authorities responsible for personal information protection. To be specific, the CAC is responsible for comprehensive planning and coordination. Then there are a number of departments of the State Council (like the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the State Administration for Market Regulation, the People's Bank of China and the National Health Commission, etc.) can enforce the PIPL within their respective industries and scope of duties and responsibilities. What's more, relevant departments of county-level and higher local governments shall also perform personal information protection duties according to the law and regulations.

According to the draft PIPL released previously, relevant authorities of county-level were authorized to impose a maximum fine under the circumstance where the unlawful acts were grave. The final version, however, only allow authorities at the provincial level or above to perform the duties of imposing penalty under this circumstance.

On 2 July 2021, China's top ride-hailing platform Didi Chuxing was announced to be probed for cybersecurity review, two days after its IPO in the US. The CAC announced that Didi's ride-hailing app had "problems of seriously violating laws on collecting and using personal information" and ordered it to be removed from mobile app stores. After the effective date of the PIPL, a number of personal information enforcement cases carried out by different departments are expected to be witnessed sooner or later.

iii. Litigation

The GDPR allows data subjects to lodge a complaint against a controller or processor in case of data right infringement. It also provides data subjects with a solution for "class action". Article 80 of the GDPR states the data subject has the right to mandate a competent third party in the field of data protection to lodge a complaint on his or her behalf. When individual claims are combined, the third party takes over as a whole against the defendants.

Similarly, under the PIPL, the personal information handler will be liable for tort damages if they infringe the personal information rights and interests of individuals. What is unique is that if the group that being victimized is large, the People's Procuratorate, consumers associations and other designated organizations may file public interest litigations.

Public interest litigations in the field of personal information protection are not rare in China now. In April 2021, China's Supreme People's Procuratorate has issued a series of typical public interest litigation cases in this field. One of the litigations was brought up by a county-level People's Procuratorate in Zhejiang Province in 2020. In this case, the authority found that an app developed by a technology company in the district has infringed on the personal information of a large number of citizens in the course of a special supervision action. In 2020, the agency filed a lawsuit against the technology company, ordering it to rectify and make a public apology. In the end, the parties reached a mediation agreement. The technology company deleted the illegally collected personal information and paid RMB 500,000 in liquidated damages. The local enforcement authority followed up and monitored the company's rectification.

IV. Further Comments from A Chinese Practitioner's Perspective

In general, China's PIPL has borrowed many techniques from the GDPR. The costs of learning and compliance with the PIPL would then be reduced a lot for companies having rolled out the GDPR compliance program. That said, the differences between PIPL and GDPR require companies to precisely adjust their privacy policies and safeguard measures to reflect the unique concepts and requirements of the PIPL. For example, the PIPL requires special treatment to children below the age of 14 years, different from the age threshold of the GDPR.

Based on the trend of social development and policy orientation in China, we believe that the impact on China's economy and people's lives brought by the PIPL would be both unexpected and unprecedented. Multi-national enterprises need to attach more emphasis to the legislative development, enforcement landscape and procedures under the PIPL. In addition, the national security flavor of the PIPL should always be born in mind. There are very serious administrative and criminal punishments for the violators who intentionally or unintentionally process personal information in breach of China's national security requirement.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]