OBA seminar: Privilege, Confidentiality and Conflicts of Interest, Oct 23.

In re Teleglobe Communications Corp.1 is an important decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit regarding the preservation of solicitor–client privilege between members of the same corporate family.2

Canadian law is clear that the legal advice provided to a company in confidence by in-house counsel is subject to solicitor–client privilege in the same way as legal advice provided by external counsel.3 What is less clear are the answers to the following, more complicated, questions. Where inhouse counsel communicates with the parent company and one or more corporate affiliates, who is the client? Is there only one client, or are there several joint clients? Is advice that is given to the parent company privileged as against the subsidiaries? Can one member of the corporate family waive privilege for all? Does in-house counsel's advice remain privileged when the interests of corporate affiliates are divergent? What happens to the privilege when the affiliates sue one another? And what practices should companies and their in-house counsel follow to protect privilege on a day-to-day basis?

Teleglobe seeks to answer all these questions. The decision upholds a parent company's right to assert privilege against its subsidiaries in certain circumstances and identifies effective steps that corporate counsel may take to protect the privilege. Although Teleglobe is a U.S. decision (decided under Delaware law), it is a clear and detailed articulation of the law in an area that has a dearth of case law in Canada. One can reasonably expect that this case will be influential for Canadian courts that are called upon to decide similar issues.

This paper reviews the Court of Appeals judgment in Teleglobe and identifies some of its implications for companies and their lawyers.

The Facts of Teleglobe

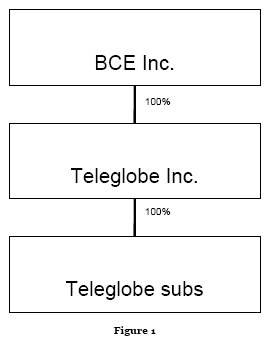

As Figure 1 shows, the corporate family in Teleglobe consisted of

- a parent company, Bell Canada Enterprises, Inc. (BCE);

- its wholly owned subsidiary, Teleglobe, Inc. (Teleglobe); and

- a group of Teleglobe's wholly owned U.S. subsidiaries (the Teleglobe subs).

The facts of the case are as follows. In 2000, BCE acquired 100% ownership of Teleglobe, and directed Teleglobe to develop a fibre optic telecommunications network called GlobeSystem. BCE caused Teleglobe and the Teleglobe subs to borrow US$2.4 billion to fund the project. These funds were depleted by 2001, at which time BCE approved a further injection of US$850 million in equity.

Around the same time, BCE began to reassess its plans for Teleglobe. The world was then experiencing the "telecom meltdown" of 2000-2001. BCE considered several options, including continuing to develop GlobeSystem, restructuring Teleglobe to turn it into a more viable business or simply cutting off funding to Teleglobe and the Teleglobe subs.

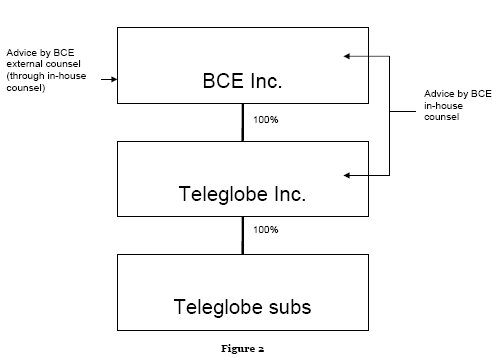

During this period of reassessment, BCE sought legal advice from both its in-house counsel and its external counsel regarding the available options. The advice received from BCE's external counsel was reviewed by BCE's in-house counsel. BCE's in-house counsel also advised Teleglobe (but not the Teleglobe subs) regarding available options during this period (see Figure 2 below). It is this legal advice from both in-house counsel and external counsel that came to be at issue in the privilege dispute, as explained below.

In April 2001, BCE cut off funding, leaving Teleglobe and its subsidiaries with no means of paying back their debt because GlobeSystem was not operational. Within weeks, Teleglobe and the Teleglobe subs filed for protection under the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act in Canada, and the Teleglobe subs filed for Chapter 11 protection in the United States.

The Teleglobe subs then sued BCE for its decision to cut off funding, alleging various forms of wrongdoing.

During the litigation, the Teleglobe subs sought access to documents containing the legal advice provided to BCE and Teleglobe prior to the termination of BCE funding in April 2001. BCE asserted solicitor–client privilege on the basis that (a) although some of the documents had been prepared for the joint benefit of both BCE and Teleglobe, these documents remained privileged as against the Teleglobe subs and (b) the advice from external legal counsel had been prepared solely for the benefit of BCE and was privileged even as against Teleglobe, despite having been viewed by BCE's in-house counsel who was advising both BCE and Teleglobe at the time.

The Teleglobe subs challenged BCE's assertion of privilege and were initially successful before the District Court in obtaining an order requiring BCE to produce the documents.

The District Court Decision

The District Court held that the Teleglobe subs, as wholly owned subsidiaries of Teleglobe, were deemed as a matter of law to be parties to any joint legal representation of BCE and Teleglobe. Consequently, the Court held, the Teleglobe subs were entitled to see the documents prepared by BCE's in-house counsel for the benefit of both BCE and Teleglobe. The District Court also held that the advice that external legal counsel provided solely for the benefit of BCE nonetheless had to be disclosed to the Teleglobe subs because this advice had been viewed by BCE's in-house counsel, who at the time was jointly representing both BCE and Teleglobe, and therefore was obligated to share the information with the client Teleglobe.

The District Court concluded that for BCE to have protected its solicitor–client privilege, it would have had to "wall off" its external lawyers from its in-house counsel and to require its in-house counsel to "clearly terminate" the solicitor–client relationship with Teleglobe.

Concerns and Interventions

The District Court decision in Teleglobe sparked considerable concern at the time among corporate inhouse counsel, and garnered media attention. Parent companies appeared to be faced with the choice of either significantly altering the operation of their in-house legal departments or forgoing solicitor–client privilege to the extent that their interests ever became adverse to those of their subsidiaries.

The concern was sufficient to cause the Association of Corporate Counsel, as well as five major multinational corporations (Alcan Corporation, Bombardier Inc., Canadian National Railway Corporation, Manulife Financial Corporation and Nortel Networks Corporation), to seek amicus curiae status in the appeal before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, seeking the reversal of the District Court's decision.

The Court of Appeals Decision

In its July 2007 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed the District Court ruling, overturning the order to produce the documents. The Court reviewed in some detail the legal principles that govern joint-client privilege and common-interest privilege, and then applied the joint-client privilege doctrine to parent-subsidiary relationships in general and the BCE/Teleglobe relationship in particular.

Joint-Client Privilege

The Court began by differentiating between the joint-client (or co-client) privilege, on the one hand, and common-interest (or community-of-interest) privilege, on the other. The Court noted that the two privileges are analytically distinct, yet are often confused.

Joint-client privilege, the Court explained, is solicitor–client privilege where two or more people consult a single lawyer on the same matter.4 Just as in single client solicitor–client relationships, the joint-client relationship arises when the co-clients convey their desire for representation, and the lawyer consents. For the joint-client relationship to be effective, there must be no substantial risk of the lawyer's being unable to fulfill the lawyer's duties to all the co-clients, whether because of conflicting interests among the co-clients or otherwise.5

The Court stressed that although the joint-client relationship may arise by implication, courts must be careful not to imply joint representation too readily. The existence of a joint-client relationship must be proved on the facts. It is not sufficient that a lawyer has several clients who share a common interest. Whether a joint-client relationship exists is determined by the understanding of the parties and the lawyer in light of the circumstances. The co-clients must collectively intend to retain the same lawyer for the same legal matter in which they have a common interest, and to share information and advice among themselves within that solicitor–client relationship. The Court noted that a wide variety of circumstances are relevant to the determination whether two or more parties intend to create a jointclient relationship, including how the parties interact with the lawyer and with each other. The same circumstances are relevant to determining the scope of any joint representation. The scope of the jointclient relationship is also limited by the extent of the legal matter of common interest.6

When co-clients and their lawyer communicate with one another, these communications are confidential for privilege purposes. Thus, unlike in the case of solicitor–client privilege, in which disclosing legal advice to another person constitutes waiving privilege, in the case of joint-client privilege the joint clients may share the legal advice among themselves without waiver.7 Indeed, they must share the advice because co-clients and their lawyer cannot keep legal advice arising from the joint-client relationship confidential from one another.

Moreover, the Court held, waiving the joint-client privilege requires the consent of all joint clients. One client may unilaterally waive privilege for its own communications with the lawyer, so long as these communications concern only the waiving client; it may not, however, unilaterally waive the privilege for any of the other joint-clients' communications or for any of its communications that relate to other joint clients.8

The flip side of information sharing among the joint-clients, the Court noted, is the "adverse litigation" exception to the rule against disclosure of the privileged information. Where joint clients subsequently find themselves adverse to one another in litigation, all communications made in the course of the joint representation are discoverable by each party.9

Common Interest Privilege

Common-interest privilege, by contrast, the Court explained, involves several parties who share a common legal interest but not the same lawyer. Common-interest privilege has its origins in the jointdefence privilege, under which lawyers for criminal co-defendants could share confidential information about defence strategies without waiving the privilege as against third parties. Over time, the jointdefence privilege was replaced with the broader common-interest privilege, which applies regardless of whether the context is criminal or civil, and regardless of whether the common legal interest involves litigation. Common-interest privilege has been recognized even in purely transactional contexts.10

Common-interest privilege protects the sharing, without waiver, of information already privileged on another basis. The information may be solicitor–client privileged legal advice, in which case the common-interest privilege operates to allow the advice to be shared with a third party who is aligned in interest. Or the information may be litigation privileged, and the common-interest privilege protects the sharing of matters relating to litigation preparation and strategy.

The Court in Teleglobe identified four conditions for the existence of common-interest privilege:

- the members of the community of interest must be represented by separate counsel;

- the members of the community of interest must share a "substantially similar legal interest" (although the legal interest need not be identical, unlike the case under the joint-client privilege);

- the communication must be made in furtherance of the shared legal interest; and

- the communication must be conveyed to the lawyer of the member of the community of interest – sharing the communication directly with the client may destroy the privilege.11

Privilege Between Parents and Subsidiaries

Having distinguished the two types of privilege, the Court held that it is the joint-client privilege that applies where a corporate parent and its subsidiary consult the same in-house counsel regarding the same legal matter. It is joint-client privilege because each corporation is a separate legal entity, and these entities are retaining a single lawyer or collection of lawyers to provide them with advice on the same legal matter. Common-interest privilege does not apply, the Court found, because that privilege applies to the sharing of privileged information between lawyers acting for separately represented clients. In the parentsubsidiary context involving in-house counsel, the clients are not separately represented.12

The Court stressed that it will always be a fact-specific question in every case whether a parent and its subsidiary have jointly agreed to seek legal advice from in-house counsel on the same question. In some cases, for example, the parent may seek legal advice from in-house counsel, and the involvement of the subsidiary may be limited to supplying relevant information. It is necessary for the court in every case to examine whether in-house counsel was providing advice to both the parent and the subsidiary, rather than advising the parent (or the subsidiary) alone.13

In the case of BCE and Teleglobe, the Court found that they had shared a joint-client relationship with in-house counsel relating to the restructuring options considered prior to April 2001. Moreover, the Court found that the Teleglobe subs had never been parties to this joint-client relationship. As a result, the Teleglobe subs were not entitled to see the documents setting out in-house counsel's legal advice to BCE and Teleglobe. This was true, notwithstanding Teleglobe's willingness to share the advice with its subsidiaries, because Teleglobe could not unilaterally waive BCE's privilege.14

The Court rejected the District Court's conclusion that the Teleglobe subs were deemed as a matter of law to be parties to the joint representation. The Court held that the existence of privilege is a question of fact, and the legal separateness of each corporation made a presumption of shared privilege inappropriate. The Court also rejected the District Court's conclusion that the Teleglobe subs were entitled to see the legal advice that external counsel had supplied to BCE alone. The District Court had relied on the fact that external counsel's advice had been reviewed by in-house counsel, finding that this meant in-house counsel was obligated to share the advice with all members of the corporate family that in-house counsel represented. The Court of Appeals held that in-house counsel was acting solely for BCE when it reviewed external counsel's advice and that BCE reasonably expected that in-house counsel would maintain that advice in confidence to protect the privilege.15 The fact that in-house counsel may have been in a conflict of interest when it reviewed the advice received by BCE (because the advice may have been adverse to the interests of Teleglobe) did not affect the analysis, as discussed below.

Cross-Appointed Directors

The Court considered whether it constituted a waiver of privilege for a parent company to disclose privileged information to a director who was cross-appointed to the board of a subsidiary.

The answer, the Court found, was no. For purposes of determining whether privileged information has been disclosed to a particular company within the corporate family, one must look at the capacity in which a corporate employee was acting when he or she received the information. Courts recognize that corporate officers and directors can "change hats" when they sit on several boards. If a director of the parent is also a director of a subsidiary, the mere fact that legal advice for the benefit of the parent was disclosed to the director does not imply waiver of privilege as against the subsidiary. One must look at whether the advice was shared with the director in his or her capacity as a director of the parent, the subsidiary or both.16

Conflicts of Interest and Privilege

At issue in Teleglobe was a divergence in the interests of BCE and its subsidiaries, as a result of BCE considering whether to (and ultimately choosing to) stop funding the subsidiaries. It was this divergence in interests that brought the privilege issues to the fore, since corporate affiliates sharing a community of interest would otherwise have no need to challenge one another's assertions of privilege.

The Court considered the effect of this conflict of interest upon the joint-client privilege. The Court concluded that if a lawyer sees the interests of joint clients diverging to an unacceptable degree, the proper course of action is to end the joint representation. However, if a jointly retained lawyer fails to do that and instead continues representing both clients when their interests become adverse, each client's confidential communications with the lawyer are privileged as against the other client. The Court concluded that counsel's failure to avoid a conflict of interest should not deprive the client of its privilege. In other words, since the privilege belongs to the client, it should not be defeated solely because the lawyer's conduct is ethically questionable.17

Applying these principles to the parent-subsidiary context, the Court noted that it was inevitable that on occasion parents and subsidiaries will see their interests diverge, particularly in spinoff, sale and insolvency situations. When this happens, the Court concluded, it would be wise for the parent to secure outside representation for the subsidiary. At the same time, the fact that the companies should have separate counsel on the matter of the spinoff or sale does not mean that the parent's in-house counsel must cease representing the subsidiary in all other matters.18

Best Practices for Preserving Privilege Within the Corporate Family

The Court in Teleglobe cautioned that it did not intend that in-house counsel should forgo advising subsidiaries or that businesses should decentralize their corporate legal departments, contrary to the District Court's ruling. The Court identified three principal proactive means of protecting a parent company's privilege.

First, parents can take care not to begin joint representations except when necessary. Second, the parent can take steps to limit the scope of any joint representation, either formally or informally. Third, as noted, the parent company can ensure that separate counsel are retained on matters in which corporate affiliates are adverse to the parent.19

Lessons from Teleglobe

The principal significance of Teleglobe is its message for corporate law departments about structuring the provision of legal services to corporate family members, both in cases where adversity between affiliates can be reasonably anticipated and more generally.

In cases of potential adversity, the lesson is simple, at least in theory: in matters where a parent may become adverse to its subsidiary, the parent should isolate the legal advice it receives from the advice provided to the subsidiary. Theory may be simpler than practice, however. One practical difficulty is in identifying potential adversity adequately in advance. A parent company may share legal advice with a subsidiary well before it could reasonably anticipate a sale or insolvency, only to find, once the sale or insolvency occurs, that the advice is subject to public disclosure in litigation with the subsidiary.

On a broader level, Teleglobe emphasizes the desirability of clearly identifying and documenting the relationships between in-house counsel and the companies they serve, to make clear who the clients are and whether a solicitor–client or joint-client relationship exists so that the privilege arises. Again, though, what is desirable in principle may be difficult to implement on a day-to-day basis. In practice, many in-house counsel perceive as unrealistic the suggestion that corporate law departments should formalize their retainer arrangements with their internal clients, specifying who is and is not a client for purposes of identifying and preserving privilege.

Teleglobe is also significant for its detailed analysis of the law of joint-client privilege and common-interest privilege, and of the application of both privileges to parent-subsidiary relationships. Most of the principles articulated in Teleglobe regarding the two types of privilege reflect the existing law in Canada, with some notable minor variations such as the requirement (under Delaware law) that information subject to common-interest privilege be shared only between counsel, and not with clients.20 The benefit of Teleglobe is that it provides a sophisticated and detailed analysis of how these two privileges apply within the corporate family – a topic on which Canadian law is relatively thin.21

At the same time, Teleglobe leaves to another day the analysis of when common-interest privilege may apply within the corporate family. Although the Court of Appeals found that it "makes the most sense" to apply the joint-client privilege analysis when members of a corporate family are represented by the same in-house counsel, the Court did not exclude the possibility that common-interest privilege might apply if multiple counsel are involved.22 One can foresee situations in which affiliates are separately represented as a result of, for example, different jurisdictional requirements, while still sharing a significant community of interest that would justify preserving privilege over the limited sharing of information and advice. Just as the Court of Appeals found that the existence of joint-client privilege is a question of fact, to be decided on a case-by-case basis, so too should the existence of common-interest privilege be determined on the facts of the particular case. It would be inappropriate to view the decision in Teleglobe as concluding, as a matter of principle, that common-interest privilege could not apply wit.

This paper was prepared for the OBA conference "Privilege, Confidentiality and Conflicts of Interest: Traversing Tricky Terrain," October 23, 2008.

* Wendy Matheson is a partner, David Outerbridge is counsel and Laura Day is a student at Torys LLP in Toronto.

Footnotes

1 In re Teleglobe Communications Corp., 493 F.3d 345 (3d Cir. 2007) [Teleglobe].

2 The decision speaks of "attorney–client privilege" rather than "solicitor–client privilege."

3 R. v. Campbell, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 565; Pritchard v. Ontario (Human Rights Commission), [2004] 1 S.C.R. 809. The same is true in the United States. See Upjohn Co. v. U.S., 449 U.S. 383.

4 The same privilege is recognized in Canada. See Sopinka et al., The Law of Evidence in Canada 2d ed. (Toronto: Butterworths Canada Ltd., 1999) at para. 14.46.

5 Teleglobe, supra note 1 at 362.

6 Ibid. at 362-3.

7 Ibid. at 363.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid. at 366.

10 Ibid. at 363-4. Common interest privilege is similarly recognized in Canada, in both litigious and non-litigious contexts. See, for example, Maximum Ventures Inc. v. De Graaf, [2007] B.C.J. No. 2355 (C.A.); Catalyst Fund Limited Partnership II v. IMAX Corp., [2008] O.J. No. 1495 (S.C.J.).

11 Teleglobe, supra note 1 at 365-6. Note, though, that some of the conditions for common interest privilege articulated by the Court of Appeals in Teleglobe do not apply in Canada. For example, the involvement of a lawyer is likely not required in Canada for common interest privilege to apply with respect to matters covered by litigation privilege. See Blank v. Canada (Minister of Justice), [2006] 2 S.C.R. 319 at para. 27.

12 Teleglobe, supra note 1 at 369-72.

13 Ibid. at 373.

14 Ibid. at 378-9.

15 Ibid. at 380-1.

16 Ibid. at 372.

17 Ibid. at 368-9, following Eureka Inv. Corp. v. Chicago Title Ins. Co., 743 F.2d 932 (D.C.Cir. 1984).

18 Teleglobe, supra note 1 at 373.

19 Ibid. at 373-4.

20 Ibid. at 369-72; see also supra note 11.

21 Both before and after Teleglobe. As of October 14, 2008, the decision in Teleglobe had not been cited in any case reported in LexisNexis Quicklaw.

22 Teleglobe, supra note 1 at 372.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.