With the EU Taxonomy Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) which entered into force on 12 July 2020, and the Disclosure Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088), the EU is pursuing the aim of steering investments and financial flows on the capital market towards "green" (financial) products and sustainable business activities. For this purpose, the EU taxonomy defines in various delegated legal instruments when a company acts in an environmentally sustainable manner. Accordingly, financial market participants must publish information on the sustainability risks of financial products or, within the framework of sustainable investments, demonstrate the EU environmental goal, the type and scope of the taxonomy-compliant economic activities in which the product is invested and the percentage share of the taxonomy-compliant activities in the overall portfolio. Furthermore, alongside large corporations already affected, small and medium-sized capital market-oriented companies and large non-capital market-oriented companies will also be required to report under the EU taxonomy from 2023. This is subject to at least two of the following three criteria relating to size: balance sheet total of EUR 20 million, net sales of EUR 40 million, average number of employees during a financial year of 250.

Motivated by pressure to be classified as sustainable, the demand for green financial products and investments is increasing. Not only banks, but also companies or pension funds are looking for new and safe investment opportunities. Due to a guaranteed Renewable Energy Act allowance over 20 years, renewable energy plants have been in high demand for some time. Due to the sharp rise in electricity prices last year, such investments have become even more attractive. For a long time, the focus was on large wind farms or ground-mounted solar plants, but due to increased competition, small rooftop solar plants are increasingly coming into focus for sustainable investments.

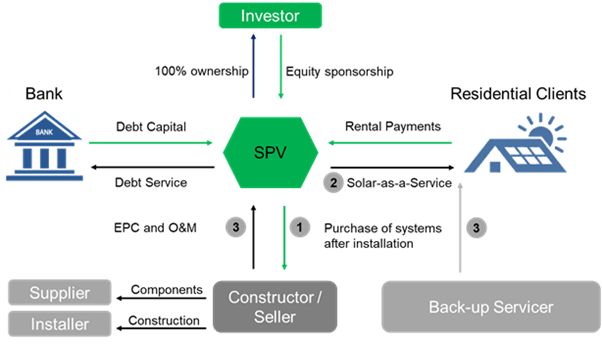

There are now more and more providers selling rooftop solar systems to private individuals under long-term contracts in various models and developing portfolios with a large number of such contracts that are suitable as a green financial product or investment.

Unlike an investment in large-scale projects, the large number of contracts with consumers particularly entails a cluster of legal risks. Not only is the probability of a judicial review of these contracts much higher, but other bodies - such as consumer protection centres - also deal in detail with the agreed regulations. In the banking sector, for example, it was seen how a single court decision triggered a wave of litigation also with other parties involved. This scenario must be avoided.

Set out below is an overview of how such a PV portfolio can look in practice (see I.), what points are important when purchasing (see II.) and what has to be considered from a legal point of view in the end customer contract (see III.).

I. Models for rooftop solar PV portfolios

II. Acquisition of a PV portfolio

In the acquisition of a PV portfolio, a distinction is usually made between three (3) phases:

- Phase 1 comprises a project status in which the PV portfolio is still in the planning phase. The seller provides a so-called special purpose vehicle (SPV), which is gradually filled with PV systems, e.g. via a project development contract. In this case, the purchase agreement structure is quite simple and the sale and purchase agreement (SPA) should contain standard guarantees for the acquisition of shelf companies (e.g. no business operations carried out so far, no employees, etc.).

- Phase 2 comprises a project status in which the PV portfolio is already under construction. The SPV to be acquired has either already concluded a large number of project contracts or is gradually being filled with PV plants on the basis of a project development contract. In this case, in addition to careful due diligence in relation to the project development agreement, care should also be taken to ensure that the seller guarantees under the SPA that it has transferred the PV assets contributed to the SPV in accordance with the project development agreement.

- Phase 3 comprises a project status in which an SPV is acquired that has already been filled with a complete PV portfolio. In addition to the aforementioned guarantees, care should be taken in this phase to ensure that certain financial assumptions and sales figures are guaranteed under the SPA. Such an SPA would usually also include a purchase price adjustment mechanism should the sales figures not yet be finalised at the time the contract is concluded.

III. Legal aspects of the end customer contract

When setting up such a portfolio or in the context of due diligence, the structuring of all contractual relationships is naturally important. However, due to the cluster of risks described at the beginning, particular importance must be attached to the end customer contracts. From the perspective of property law, civil law, energy law and financial law, there are different risks that need to be taken into account when drafting and reviewing the corresponding contracts.

1. Property law aspects

The end customer contract should in principle be designed in such a way that the PV system remains the property of the SPV. Otherwise the PV system loses not only its quality as a security deposit, but also its purpose as a rental object, as it does not seem to make much sense from the customer's point of view to rent his own property. Care must be taken that the PV system is either firmly connected to the building (often not the case) or is considered necessary for the building. Such a necessity can arise both from a legal point of view (obligation to erect) and from an actual point of view (own power supply). In order to counter the risk of legal transfer of ownership, either the prior registration of an easement is required or the agreement of the contribution of the PV system for a temporary purpose. However, according to established case law, the latter depends on the entire content of the contract, so that a temporary purpose cannot simply be expressly agreed. In particular, the term of the contract, takeover obligations as well as purchase options can contradict such a temporary purpose, which must be taken into account when drafting the contract.

2. Civil law aspects

From a civil law perspective, it should generally be noted that contracts with consumers are subject to the German law on general terms and conditions (Sections 305 - 310 German Civil Code). Accordingly, all contractual provisions must be carefully checked for their legality. This applies in particular to termination, liability and transfer clauses.

3. Energy law aspects

From an energy law perspective, the renewable energy surcharge is still of particular importance. For a long time, the renewable energy surcharge was the largest state-based cost factor in the electricity price. For the profitability of corresponding rooftop PV models, it was therefore of considerable importance that the tenant does not pay a renewable energy surcharge when supplying himself with electricity from the roof. However, this is only possible if the tenant is classified as the operator of the PV system and thus a so-called self-supply constellation exists (Section 61b para. 2 Renewable Energy Act). Similar to ownership, the operator status is assessed on the basis of the entire contract under the operator criteria defined by the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) (actual material control, operational control, economic risk). When drafting the contract, therefore, particular attention must be paid to the regulations on risk distribution and the rights and obligations of the tenant with regard to the PV system. With the abolition of the renewable energy surcharge in July 2022, this problem will be a thing of the past.

4. Financial law aspects

Finally, in the case of long-term contracts in which the tenant ultimately pays off the PV system and may purchase it at the end, there is a risk that these contracts will be classified as finance leases by the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin). The sale of such a financial product is subject to authorisation and requires approval by BaFin. Due to the financial and organisational effort involved, the contract should therefore be structured in such a way that it does not amount to such a finance lease. In this context, the term of the contract, the warranty rights and regulations on accidental loss are of particular importance. In order to secure the model, a written negative confirmation can be requested from BaFin, with which the authority confirms that no finance leasing exists.

IV. Conclusion

In conclusion, rooftop PV systems are certainly suitable as a green financial product, but are characterised by a relatively high degree of complexity, not least with regard to the various legal aspects that need to be considered for successful implementation. In particular, the aspects mentioned under III. should be legally examined and, if necessary, adapted to the respective project structure before an investment decision is made.

Originally published 22 March 2022

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.