Governments are increasingly committing to a circular economy - an economy that aims to maximise the use of resources by reducing, reusing and recycling materials. Many governments have developed container refund schemes (also called container deposit schemes) as part of their circular economy policies. Most Australian states and territories now have a scheme, with Tasmania and Victoria to introduce theirs in 2023.

Container refund schemes work by changing consumer behaviour

Container refund schemes aim to reduce litter and increase recycling by changing people's behaviour. The schemes use financial incentives to achieve this - by offering consumers 10 cents for each container they return to a designated depot rather than littering or putting in the garbage.

Littering has been decreasing across Australia

Litter is any solid waste object (disposable item or resource) that has been thrown, blown or left in the wrong place. 1 Until 2020, the National Litter Index (NLI) was used to monitor the amount of litter across Australian states and territories. 2 Based on the NLI, the quantity and volume of litter has fallen nationally since 2005 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - National Litter Index, 2005-19

Source: Queensland Government 2021, Comparison between Queensland and national average trend over time, Open Data Portal.

Littering rates vary by type of waste, with cigarette butts and packaging accounting for the greatest number of items (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Breakdown of litter, by count, 2017-19

Source: Keep Australia Beautiful National Association 2019, National Report 2018 - 2019, National Litter Index.

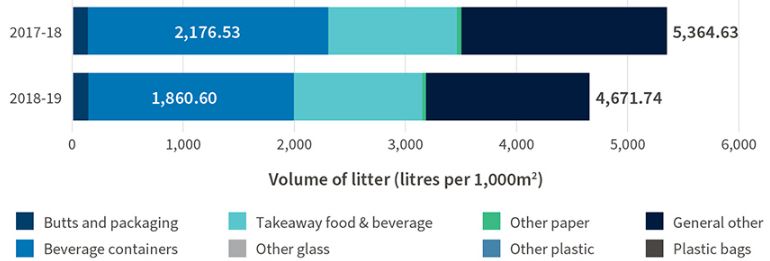

The data tells a different story if it is presented by volume rather than by number. Although there may be fewer beverage containers than cigarette butts, containers make up a much larger proportion of the total volume of national litter (Figure 3). While the number of litter items was similar in 2017-18 and 2018-19, the volume fell by 12.9 per cent. The biggest contributor to this reduction was beverage containers.

Figure 3 - Breakdown of litter, by volume, 2017-19

Source: Keep Australia Beautiful National Association 2019, National Report 2018 - 2019, National Litter Index.

Container refund schemes reduce littering, but don't significantly increase recycling

State and territory governments have targeted beverage containers because they make up a large proportion of the volume of litter we see in our parks and shopping centres and on our beaches. Perhaps more relevant to the goals of a circular economy, beverage containers are recyclable, whereas other litter items such as cigarette butts are not.

Australia's container refund schemes may have had some success in reducing littering. Regional data shows that all states and territories that recently introduced a scheme have reduced the amount of eligible containers found in litter collections - some by as much as 60 per cent. 3 However, a closer look at recycling data reveals that, although total recycling rates have steadily increased over time, the introduction of container refund schemes has not had a significant impact on recycling rates. For example, in Queensland, which introduced its scheme in November 2018, recycling rates of all materials increased by only 4 per cent - from 38 per cent that year to 42 per cent in 2019. A similarly marginal increase occurred from 2017 to 2018 - from 36 per cent to 38 per cent - when a scheme was not in place. 4

Container refund schemes contribute to the aims of a circular economy - but not on their own

Container refund schemes can effectively contribute to the aims of a circular economy: to maximise the use of resources by reducing, reusing and recycling them.

Reduce

The direct cost of these schemes falls on manufacturers, which then seek to pass these costs on to retailers, and ultimately consumers. Responding to these price rises, consumers buy fewer containers. For example, consumption of non-alcoholic beverages decreased by 6.5 per cent in the first year after a scheme was introduced in Queensland. In NSW, household spending on 25-40 packs of eligible containers fell by an average of 20 per cent after its scheme was introduced. Falling demand for containers means fewer will be produced in the first place.

Recycle

Many people dispose of their beverage containers in their household recycling bin, which is collected by the local council. Glass containers are mixed with other recycling and if they shatter during transit, glass shards can penetrate cardboard or plastics. This renders them less valuable, or potentially unrecyclable. Encouraging consumers to recycle glass separately through a container refund scheme creates higher quality and higher value recycled material streams for the recycling and remanufacturing markets.

Source: Queensland Productivity Commission 2020, Container refund scheme price monitoring review - final report, January 2020; IPART 2018, NSW Container Deposit Scheme - Monitoring the impacts on container beverage prices and competition, December 2018.

However, many factors affect recycling rates, and container refund schemes are just one mechanism governments can use to change people's recycling behaviour. For example, many states have introduced levies that increase the cost of disposing of waste in landfill. This type of mechanism may have had a greater impact on shifting material from landfill to recycling as it targets a wider range of materials than just beverage containers.

How do we know if a container refund scheme will be effective?

To understand the effectiveness of container refund schemes, it is crucial to define what policy problem is being addressed. Governments have identified two policy objectives - reducing littering and increasing recycling - but implemented just one mechanism to achieve both.

How do we reduce litter?

Container refund schemes use a tax and refund method to encourage

people to reduce littering and instead return containers to a

collection point. Evidence shows this mechanism works, although

other methods, such as enforcement, education, extended producer

responsibility or clean-ups, may achieve similar outcomes.

How do we increase recycling?

It is less clear whether these schemes have a significant impact on

recycling - the mechanism supports the collection of containers but

does not guarantee recycling unless the economic return from

recycling exceeds disposal to landfill, or if recycling is mandated

by law. Other mechanisms such as waste levies may be a more

effective way to increase recycling.

How do we do both?

More than one policy instrument is needed to achieve both

objectives. A container refund scheme alone will not increase

recycling rates unless the returns from recycling exceed those of

disposal to landfill. This is why these schemes are just one part

of a general waste strategy that includes measures to change the

relative cost of recycling and disposal to landfill.

How we can help

When thinking about policies to achieve a circular economy, it is necessary to apply some fundamental economic principles:

- Understand the policy problem and desired objectives

- Develop as many policy instruments as there are objectives

- Evaluate the costs and benefits of other options that might achieve the same objectives

- Design each instrument in a way that best targets the identified objective.

At FTI Consulting, our Economic & Financial Consulting team can guide you through the policy evaluation process and ensure that you design a container refund scheme or other waste policy that efficiently and effectively meets its objectives.

Footnotes:

1: New South Wales Government 2021, NSW Litter Report 2016-2020, March 2021.

2: This index has been replaced with the Australian Litter Measure (AusLM). For more on AusLM, see Queensland Government 2021, Australian Litter Measure (AusLM)- Field Guide, September 2021.

3: Keep Australia Beautiful National Association 2019, National Report 2018 - 2019, National Litter Index.

4: Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment 2020, National Waste Report 2020, Appendix B, Figure 21.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.