- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy industries

I. Introduction

This report1 recommends clarifications to the rules under Section 9562 to improve the efficiency of debt-financing transactions. As explained in more detail below, Section 956 effectively limits the extent to which indebtedness of a borrower or issuer that is a United States person (a "US borrower")3 can be guaranteed by a controlled foreign corporation (a "CFC")4 related to the US borrower, or secured by pledges of the stock of the CFC, without giving rise to deemed dividends to the US borrower of any of the CFC's undistributed earnings that were not previously subject to US federal income taxation. While the impact of Section 956 was limited by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (the "TCJA"),5 Section 956 continues to have a material impact on debt financings by US borrowers, and uncertainties about the proper interpretation of Section 956 sometimes lead to lenders and other holders of indebtedness (collectively, "lenders") unnecessarily being asked to forgo certain credit support from US affiliates of US borrowers and/or to forgo certain customary commercial rights that should not raise Section 956 concerns.

A. Application of Section 956 to Debt Financings

Section 956 is one of the anti-deferral rules in "Subpart F" (i.e., Sections 951 through 965) designed to prevent certain US taxpayers that own CFCs from indefinitely avoiding US federal income taxation with respect to the undistributed earnings of the CFCs. As explained in more detail below, Section 956 generally requires significant US shareholders of a CFC to include currently in gross income their respective shares of the CFC's undistributed earnings and profits to the extent the CFC holds (or is deemed to hold) United States property (including a debt obligation of certain US affiliates of the CFC).

If a non-US corporation is a CFC at any time during any taxable year of the corporation, every person who is a "United States shareholder"6 of the corporation at any time during that taxable year, and who owns (actually or constructively (in accordance with Section 958(a))) any stock in the corporation on the last day of that taxable year on which the corporation was a CFC, shall include in gross income (for the United States shareholder's taxable year in which or with which the CFC's taxable year ends) "the amount determined under Section 956 with respect to such [United States] shareholder for such year. . . ."7 The amount determined under Section 956 with respect to a United States shareholder of a CFC for any taxable year generally is the lesser of (1) the excess (if any) of (A) such shareholder's pro rata share of the average amounts of "United States property" held (directly or indirectly) by the CFC as of the close of each quarter of such taxable year, over (B) the amount of earnings and profits described in Section 959(c)(1)(A) with respect to such shareholder (i.e., the amount of earnings and profits previously taken into income under Section 956) and (2) such shareholder's pro rata share of the "applicable earnings" of such CFC (i.e., generally the current or accumulated earnings and profits of such CFC to the extent not previously taken into income under Section 956 (or excluded from income under Section 959(a)(2))).8

While "United States property" includes a debt obligation of certain US affiliates of a CFC,9 it is unusual in our experience for Section 956 to arise as result of a CFC making loans to, or otherwise acquiring debt obligations of, the CFC's US affiliates. Potential Section 956 concerns typically in our experience arise when a CFC is asked to provide credit support with respect to third-party indebtedness of a US affiliate (i.e., to provide a guarantee of, or pledge assets in support of, a loan made by a third party to such US affiliate). Section 956(d) provides that, for purposes of Section 956, a CFC that guarantees, or pledges assets in support of, indebtedness of a United States person shall (to the extent provided in the Regulations) be treated as holding such indebtedness. The Regulations reiterate the general rule and extend the rule to cover an "Indirect Pledge or Guarantee," providing that "if the assets of a [CFC] . . . serve at any time, even though indirectly, as security for the performance of an obligation of a United States person, the [CFC] . . . will be considered a pledgor or guarantor of that obligation."10 The Regulations further provide that "[f]or purposes of this paragraph, a pledge of stock of a [CFC] representing at least 66⅔ percent of the total combined voting power of all classes of voting stock of such corporation will be considered an indirect pledge of the assets of the [CFC] if the pledge is accompanied by one or more negative covenants or similar restrictions on the shareholder effectively limiting the corporation's discretion to dispose of assets and/or incur liabilities other than in the ordinary course of business."11

The foregoing provisions of the Section 956 Regulations governing indirect pledges and guarantees by a CFC (the "Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule") generally serve as the guidepost for structuring debt financings by US borrowers without running afoul of Section 956. Lenders providing debt financing to a US borrower that owns both US operations/subsidiaries and the stock of CFCs typically expect full credit support (guarantees and pledges of assets) from the US borrower and its US affiliates but understand that there will be no guarantees or pledges of assets from the CFCs and that pledges of the voting stock of the CFCs will not exceed 65%12 of such stock. However, uncertainties about the application of the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule (and about the related question of what constitutes an "obligation" of a United States person) sometimes frustrate these commercial expectations by resulting in lenders unnecessarily being asked to forgo material US credit support and/or to forgo certain customary commercial rights that should not raise Section 956 concerns. As discussed in more detail below, these uncertainties include:

1. Whether a pledge of indebtedness of a CFC ("CFC Debt") held by a US borrower or US guarantor violates the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule;

2. The treatment of a US entity that owns no material assets other than the stock (or stock and indebtedness) of CFCs (so called "CFC Holding Companies" ("CFC Holdcos") or "Foreign Subsidiary Holding Companies" ("FSHCOs"));

3. The treatment of the pledge of the equity of, or a guarantee provided by, a US entity that is disregarded for US federal income tax purposes (a "disregarded entity") and that owns stock of a CFC;

4. Whether a US entity's guarantee of CFC Debt should be considered an "obligation" of a United States person for purposes of Section 956; and

5. Whether an arrangement among lenders, upon a default, to ratably share/reallocate a tranche of loans to a US borrower (on the one hand) and a tranche of loans to a related CFC (on the other hand) such that each lender holds a proportionate share of each tranche of loans (a so-called "collateral allocation mechanism" ("CAM") or "debt allocation mechanism" ("DAM")) raises Section 956 concerns.

B. Section 956 Remains Important after the TCJA

Section 956 and the foregoing uncertainties that surround it continue to play a material role in US debt financings, notwithstanding the impact of the TCJA. While the enactment of the "GILTI" provisions of the TCJA13 reduced the opportunity for United States shareholders of a CFC to defer taxation of the CFC's undistributed earnings, some meaningful deferral is still permitted.14 In certain circumstances, Section 245A (which was added by the TCJA) permits the untaxed, undistributed earnings of a CFC to be repatriated free of US federal income taxation, potentially reducing or eliminating the impact of Section 956.15 But Section 245A applies only to corporate United States shareholders, not individuals,16 and is limited to the "foreign-source" portion of a CFC's undistributed earnings.17 Moreover, there are a number of uncertainties regarding the application of Section 245A.18 Many US corporate borrowers are unwilling to bear any risk with respect to this issue or to devote the time and resources needed to analyze it. Accordingly, while approximately seven years have passed since the TCJA was enacted, we believe that US borrowers (including US corporate borrowers) generally take the same approach to avoiding potential Section 956 income inclusions as US borrowers did prior to enactment of the TCJA.

II. Summary of Our Recommendations

As discussed in more detail below, we recommend that:

1. it be confirmed that, under current law, a pledge of CFC Debt by a US borrower or US guarantor does not violate the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule;

2. guidance be provided as to when, under current law, the guarantee of indebtedness of a US borrower by a CFC Holdco or FSHCO raises Section 956 concerns;

3. it be confirmed that, under current law, for purposes of determining the Section 956 consequences of the pledge of the equity of, or a guarantee provided by, a disregarded entity that owns stock of a CFC, a disregarded entity should be treated no differently than a regarded entity;

4. it be confirmed that, under current law, a guarantee of the indebtedness of a CFC by a US affiliate is not an "obligation" of a United States person for purposes of Section 956; and

5. it be confirmed that, under current law, a CAM/DAM among lenders to a US borrower and lenders to a related CFC does not raise Section 956 concerns.

III. Discussion of Our Recommendations

A. Pledges of the Indebtedness of a CFC

It should be confirmed that, under current law, a pledge by a US borrower or US guarantor of CFC Debt held by such US person does not violate the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule.

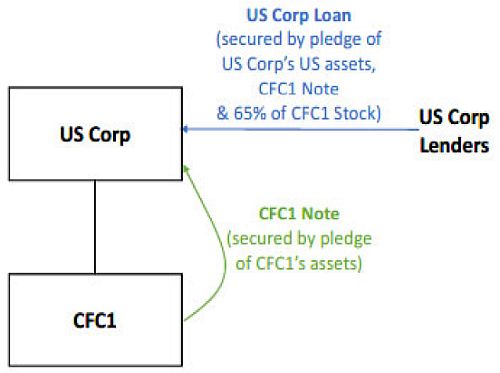

Consider the following scenario. A US corporation ("US Corp") conducts a US business directly and owns 100% of the stock of "CFC1," a non-US corporation engaged in a non-US business. CFC1 has only one class of stock outstanding. In addition to owning the stock of CFC1, US Corp owns a note issued to it by CFC1 (the "CFC1 Note"). The CFC1 Note is a bona fide indebtedness of CFC1 that is properly treated for US federal income tax purposes as indebtedness of CFC1. The CFC1 Note is secured by all of the assets of CFC1.

US Corp would like to borrow funds from a group of third-party lenders (the "US Corp Lenders") to expand US Corp's US operations. The US Corp Lenders propose to make a loan to US Corp (the "US Corp Loan"), which loan would be secured by a pledge of (a) all of the US assets of US Corp, (b) 65% of the outstanding stock of CFC1 and (c) the CFC1 Note. CFC1 would not provide a guarantee of the US Corp Loan or pledge any collateral in support thereof, but CFC1 would be designated a "Restricted Subsidiary" under the US Corp credit agreement and thereby made subject to negative covenants that limit the ability of US Corp and its Restricted Subsidiaries to dispose of their assets or incur liabilities. In contemplation of the US Corp Loan, the CFC1 Note would be amended to include a "cross-default provision" (i.e., to provide that a default with respect to the US Corp Loan would trigger a default with respect to the CFC1 Note), entitling the US Corp Lenders (as pledgees of the CFC1 Note), upon a cross-default, to accelerate repayment of the CFC1 Note and to exercise any other applicable creditors' rights with respect to the CFC1 Note.

While a pledge of the CFC1 Note would provide the US Corp Lenders with some direct access to the assets of CFC1 upon a default of the US Corp Loan, such access arises solely in the capacity of a creditor of CFC1 with respect to an indebtedness of CFC1 (the CFC1 Note), and such access is limited to the unpaid balance of the CFC1 Note. CFC1 could repay the CFC1 Note in whole or in part at any time without giving rise to any dividend income to US Corp. It would be illogical for the pledge of the CFC1 Note to result in adverse Section 956 consequences to US Corp when the pledgee's recovery in respect of the note could never exceed the unpaid balance of the note and an actual repayment of the note immediately (or at any future time) could never result in any dividend income to US Corp. This argument should be unaffected by whether or not (a) the CFC1 Note will cross-default (and thereby accelerate) upon a default with respect to the US Corp Loan or (b) the CFC1 Note is secured by the assets of CFC1 (including any bona fide indebtedness of other CFCs owned by CFC1), with the possible exception of 66⅔% or more of the outstanding voting stock of other CFCs.19

Accordingly, while a pledge of CFC Debt as collateral to support the indebtedness of a US borrower might be viewed in a general economic sense as an indirect pledge of the CFC's assets in support of such US indebtedness, that should not be the case for purposes of Section 956.

B. CFC Holdcos/FSHCOs

Guidance should be provided as to when the guarantee of a US borrower's indebtedness by a CFC Holdco or FSHCO (collectively, a "CFC Holdco") raises Section 956 concerns.

The CFC Holdco concept has become prevalent in US debt financings for many years. A CFC Holdco is generally defined in debt-financing documents as a domestic subsidiary of a US borrower (or of a US parent of the US borrower) that owns no material assets other than stock (or stock and indebtedness) of one or more non-US subsidiaries of the US borrower (or of a US parent of the US borrower) that are CFCs. A common alternative to the "no material assets" formulation is a "substantially all of the assets" formulation — i.e., that substantially all of the assets consist of stock (or stock and indebtedness) of one or more non-US subsidiaries of the US borrower (or of the US parent of the US borrower) that are CFCs.

The CFC Holdco concept is often utilized for commercial reasons (i.e., to save the borrower group the effort and expense of pledging 65% of the stock of each CFC owned by the borrower group by instead isolating some or all of the CFCs in one US holding company and pledging 65% of the stock of the holding company). For this reason, a CFC Holdco is typically treated as an "Excluded Subsidiary," i.e., as a subsidiary that does not provide a guarantee or pledge any collateral in support of the debt in question, and the pledge of the voting stock/equity of a CFC Holdco is typically limited to 65% of the outstanding voting stock/equity (as if the CFC Holdco were itself a CFC). But the treatment of a CFC Holdco as an Excluded Subsidiary (and the related 65% voting stock pledge limitation) is also partly for tax reasons — uncertainty as to whether a guarantee by, or a pledge of 66⅔ % or more of the equity of, a domestic subsidiary with no material assets other than the stock of a CFC may be viewed by the Internal Revenue Service (the "IRS") as a de facto pledge of the CFC stock (in violation of the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule).

Lenders generally have no concern as a commercial matter with treating a CFC Holdco as an Excluded Subsidiary if the CFC Holdco owns no material assets other than stock of one or more subsidiaries that are CFCs. But some borrowers propose expanded definitions of a CFC Holdco that include other assets that may be material to lenders, including CFC Debt, intellectual property used in non-US jurisdictions, cash and cash equivalents and/or other assets incidental to any of the foregoing. While the parties should be free to negotiate this point as a commercial matter, uncertainty as to when a guarantee by a CFC Holdco raises Section 956 concerns may impede this process.

Moreover, in the absence of tax guidance, market participants generally treat the applicable contractual definition of a CFC Holdco as a de facto Section 956 standard, which may lead to a CFC Holdco unnecessarily being treated as an Excluded Subsidiary or to a subsidiary that is not a CFC Holdco providing a guarantee that raises Section 956 concerns. This issue is compounded by the fact that both common formulations of the CFC Holdco definition — the "no material assets" version and the "substantially all of the assets" version — are subjective and context dependent.20

For example, assume that a US corporation seeking a loan ("US Borrower") has a direct, wholly-owned US corporate subsidiary ("US Sub"). US Sub owns the stock of a CFC and also conducts a segment of the US Borrower corporate group's US business (the "US Sub Division"). The value of the US Sub Division is relatively small in relation to the value of the CFC stock but the US Sub Division is nonetheless valuable to the lenders as collateral. US Borrower is willing as a commercial matter to have US Sub guarantee the loan (and to have US Sub pledge the assets of the US Sub Division as collateral) but is hesitant to do so because of uncertainty as to whether a guarantee by US Sub might be treated for purposes of Section 956 as a de facto pledge of the stock of the CFC. Regardless of whether US Sub is a CFC Holdco under the applicable debt-financing document, what standard should US Borrower use to make the Section 956 determination?

We believe that the proper standard under current law for determining whether Section 956 should apply to guarantees by (and pledges of 66⅔% or more of the voting stock of) a CFC Holdco or similar entity is whether such entity is intended to circumvent the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule (i.e., to provide lenders with a de facto pledge of 66⅔% or more of the voting stock of a CFC). We do not believe that a typical CFC Holdco raises such concerns. The decision to create and/or maintain a CFC Holdco is typically left to the US borrower group. Lenders rarely require a CFC Holdco and generally do not prohibit a US borrower that chooses to create the CFC Holdco from eliminating the CFC Holdco at any time (e.g., by transferring material US assets to such entity (such that it ceases to be a CFC Holdco) or by merging the CFC Holdco with, or liquidating the CFC Holdco into, another affiliate that is not a CFC Holdco). A CFC Holdco generally is not prohibited from engaging in commercial activities that could give rise to competing creditors (e.g., trade creditors or potential tort creditors) with respect to the CFC stock owned by the CFC Holdco.21

Accordingly, we believe that a guarantee from a CFC Holdco or similar entity (or a pledge of 66⅔% or more of the voting equity of such entity) should be viewed as a de facto pledge of the voting stock of the CFCs owned by such entity (and thereby raise Section 956 concerns) only if (1) such entity has no material assets other than the stock of subsidiaries that are CFCs22 and (2) the borrower and the lenders have an agreement, or an express or implied understanding, that the borrower will create and maintain such entity and subject such entity to atypical negative covenants that effectively preclude the existence of competing creditors in such entity. Any such guidance should confirm that it applies uniformly regardless of whether the CFC Holdco or similar entity is treated, for US federal income tax purposes, as a corporation, a partnership or a disregarded entity.23

C. Pledges of the Equity of, and Guarantees Provided by, a Disregarded Entity that Owns a CFC

For purposes of determining the Section 956 consequences of the pledge of the equity of, or a guarantee provided by, a disregarded entity that owns stock of a CFC, a disregarded entity should be treated no differently than a regarded entity.

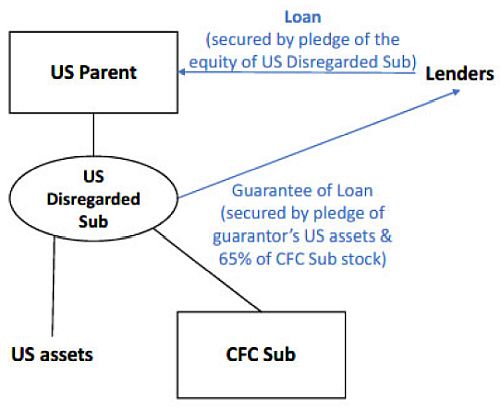

Consider the following scenario. A US corporation ("US Parent") conducts a US business through a direct, wholly-owned US limited liability company subsidiary that is a disregarded entity ("US Disregarded Sub"). In addition to conducting its US business, US Disregarded Sub owns 100% of the stock of "CFC Sub," a non-US corporation engaged in a non-US business. CFC Sub has only one class of stock outstanding (i.e., all of its outstanding stock is voting stock). The value of the US business owned by US Disregarded Sub is substantial in relation to the value of the outstanding stock of CFC Sub.24

US Parent would like to borrow money from a group of third-party lenders to expand the US operations of US Disregarded Sub. The lenders propose to make a loan to US Parent, which loan would be guaranteed by US Disregarded Sub. The guarantee would be secured by a pledge of all of the US assets of US Disregarded Sub and a pledge of 65% of the outstanding stock of CFC Sub. In addition, US Parent, as borrower, would pledge 100% of the equity of US Disregarded Sub.25 CFC Sub would not guarantee the loan or pledge any collateral in support thereof, but CFC Sub, like US Disregarded Sub, would be designated a "Restricted Subsidiary" under the credit agreement and thereby made subject to a number of negative covenants that limit the ability of US Parent and its Restricted Subsidiaries to dispose of their assets or incur liabilities.

If US Disregarded Sub were a regarded US entity (i.e., a corporation or a partnership), there should be no doubt that the foregoing financing structure would not give rise to any adverse Section 956 implications. By limiting the pledge of the stock of CFC Sub to less than 66⅔% of the outstanding stock of CFC Sub, the parties should avoid the application of the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule, notwithstanding the fact that CFC Sub is subject to negative covenants that limit CFC Sub's ability to dispose of assets and incur liabilities.

In our experience, practitioners generally believe that the Section 956 treatment of the foregoing financing structure should be no different as a result of US Disregarded Sub's disregarded entity status. But, due to the lack of guidance, there is some uncertainty on the point. Because the owner of the equity of a disregarded entity is deemed to own all of the assets of the disregarded entity,26 could the IRS assert that the pledgee of the equity of a disregarded entity is deemed to have received a pledge of all of the assets of the disregarded entity? In the foregoing scenario, such a conclusion would mean that the pledge of 100% of the equity of US Disregarded Sub is a deemed pledge of 100% of the stock of CFC Sub, which would trigger the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule with respect to CFC Sub. Moreover, such a conclusion would effectively preclude US Parent from pledging any material portion of the equity of US Disregarded Sub because a pledge of even 5% of the equity of US Disregarded Sub, when coupled with the actual pledge of 65% of the stock of CFC Sub, would trigger the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule with respect to CFC Sub.27

Similarly, could the IRS assert that a guarantee from a disregarded entity should be treated as a deemed pledge of the disregarded entity's assets (by the regarded owner of the disregarded entity) because the guarantee provides the benefited lenders with a claim against those assets that is structurally senior to any outstanding indebtedness of the regarded owner that is not guaranteed by the disregarded entity? Such a conclusion would effectively preclude US Disregarded Sub from providing any credit support in respect of the loan to US Parent (even though US Disregarded Sub owns a substantial US business) because US Disregarded Sub owns a CFC.

We believe it should be confirmed that, under current law, for purposes of analyzing the foregoing issue, a disregarded entity should be treated no differently than a regarded entity.

Disregarded entity status has no effect on the creditors' rights of the applicable lenders. A lender foreclosing on a pledge of the equity of a disregarded entity that owns a CFC obtains no creditors' rights whatsoever against the disregarded entity or any of the disregarded entity's assets (including the stock of the CFC), and is structurally subordinated to all creditors (secured and unsecured) of the disregarded entity.

Similarly, an unsecured guarantee by a disregarded entity that owns a CFC does not provide the benefited lenders with any enhanced creditors' rights relative to other creditors of the disregarded entity. In the foregoing scenario, the benefited lenders' creditors' rights with respect to the 35% of the stock of the CFC not pledged to such lenders are no greater than the creditors' rights of any competing creditor of the disregarded entity (such as trade creditors or potential tort creditors of the US business).

Support for the foregoing argument may be found in four IRS private letter rulings ("PLRs")28 that addressed the appropriate treatment of disregarded entities for purposes of Treas. Reg. §1.1001-3 (the "Debt Modification Regulations"). These PLRs conclude that, for purposes of the Debt Modification Regulations, indebtedness of a disregarded entity should be treated as a recourse obligation of the disregarded entity as opposed to a nonrecourse obligation of its regarded owner (i.e., the entity's disregarded status should be ignored), because the entity's disregarded status has no effect on the respective legal rights and obligations of the borrower and the lenders and any changes thereto.

The most recent of these PLRs, Priv. Ltr. Rul. 202337007, addressed the question of whether there would be a "significant modification" of the indebtedness of a borrower that was a disregarded subsidiary of a partnership (which significant modification would have resulted in a deemed exchange of the indebtedness for deemed new indebtedness and a corresponding recognition of cancellation of indebtedness income ("CODI") by the partners of the partnership) if the disregarded borrower first became a disregarded subsidiary of a corporation (instead of a partnership), and then itself converted to corporate status. The three earlier PLRs addressed a similar question of whether there would be a "significant modification" of the indebtedness of a corporate borrower if the corporate borrower became a disregarded entity. While the technical analysis in each of the PLRs differs somewhat, each PLR concludes that, for purposes of the Debt Modification Regulations, indebtedness of a disregarded entity should be considered a recourse indebtedness of the disregarded entity, notwithstanding the entity's disregarded status. In reaching this conclusion, each PLR emphasized that the borrower's disregarded status did not affect the respective commercial rights and obligations of the borrower and the lenders.

For example, in Priv. Ltr. Rul. 202337007, the IRS ruled that the transaction, including the borrower's conversion from a disregarded entity to a corporation, did not result in a change in obligor or a change in the recourse nature of the indebtedness in question, emphasizing that:

Pursuant to the Act [the applicable commercial law], the conversion of LLC1 [the predecessor disregarded entity] into Subsidiary 2 [the successor corporation] will not affect the legal rights or obligations between Debt holders and LLC1 because, as a matter of State A law, Subsidiary 2 will remain the same legal entity as LLC1. Debt holders will continue to have exactly the same legal relationship with Subsidiary 2 that they had previously had with LLC1.

Pursuant to the Act, Debt holders' legal rights against Subsidiary 2 [the successor corporation] with respect to payments and remedies will be the same legal rights that Debt holders had against LLC1 [the predecessor disregarded entity]. The obligations and covenants from Subsidiary 2 to Debt holders will be the same as the obligations and covenants from LLC1 to Debt holders.

Priv. Ltr. Rul. 200315001 reached the same conclusion based on the same analysis. The other two PLRs concluded that there was a change in obligor,29 but, like the two foregoing PLRs, that there was no change in the recourse nature of the indebtedness in question (i.e., that the indebtedness in question became a recourse obligation of the successor disregarded entity).30

For the reasons noted above, we believe that an entity's disregarded status should be irrelevant in analyzing the foregoing issue under Section 956.

D. Guarantee of Indebtedness of a CFC by a US Affiliate

For Section 956 purposes, an "obligation" of a United States person should be limited to a primary debt obligation of a United States person (that results in the tax-free receipt of cash, property or services by a United States person) and should not include a United States person's guarantee of an indebtedness of a CFC.31 Accordingly, if an indebtedness of a CFC (the "CFC Borrower") is guaranteed by both a related CFC (the "CFC Guarantor") and a United States shareholder of the CFC Borrower, the guarantee by the CFC Guarantor (the "CFC Guarantee") should not implicate Section 956, even though (as a commercial law matter) the CFC Guarantee is both a guarantee of the underlying indebtedness of the CFC Borrower and of the guarantee obligation of the other guarantor (the United States shareholder). The IRS reached this conclusion in two technical advice memoranda issued in the early 1980s,32 but the lack of precedential authority33 on the point creates unnecessary uncertainty.

Section 956 should not apply to the United States shareholders of a CFC unless the CFC provides credit support for a borrowing that results in the receipt of cash, property or services by a US affiliate of the CFC without a corresponding recognition of dividend income. Congress made this point clear in 1976, when it narrowed the definition of "United States property" by adding the following new exception to such definition in Section 956(c)(2)(F):

the stock or obligations of a domestic corporation which is neither a United States shareholder . . . of the [CFC], nor a domestic corporation, 25 percent or more of the total combined voting power of which, immediately after the acquisition of any stock in such domestic corporation by the [CFC], is owned, or is considered as being owned, by such United States shareholders in the aggregate;

Prior to this amendment, any investment in the stock or obligations of any United States person (even if the United States person were unrelated to the CFC and its United States shareholders) was deemed to be an investment in United States property. The legislative history to this amendment confirmed that Section 956 was aimed at (and should be limited to) situations in which United States shareholders of a CFC would otherwise effectively achieve a tax-free repatriation of the CFC earnings:

The reason why [Section 956] was adopted was the belief that the use of untaxed earnings of a controlled foreign corporation to invest in U.S. property was 'substantially the equivalent of a dividend' being paid to the U.S. shareholders. . . .

In the committee's view, since the investment by a foreign corporation in the stock or debt obligations of a related U.S. person or its domestic affiliates makes funds available for use by the U.S. shareholders, it constitutes an effective repatriation of earnings which should be taxed.34

A guarantee of the indebtedness of a CFC by a United States shareholder of the CFC does not result in any tax-free receipt by a United States shareholder (or any US affiliate thereof) of any cash, property or services and therefore should not be considered an "obligation" for purposes of Section 956. The IRS reached this conclusion in two technical advice memoranda.

In Tech. Adv. Mem. 8042001, a third-party indebtedness of a CFC ("CFC F") was guaranteed, jointly and severally, by several guarantors, including a United States shareholder of CFC F ("US Shareholder A") and a related CFC of which US Shareholder A was also a United States shareholder ("CFC B"). The question was whether CFC B, by virtue of (1) CFC B's joint and several guarantee of the third-party indebtedness of CFC F and (2) US Shareholder A's pledge of the stock of CFC B, was guaranteeing the "obligation" of a United States person (i.e., the guarantee obligation of US Shareholder A) for purposes of Section 956. The IRS concluded, based on the foregoing rationale, that US Shareholder A's guarantee was not an "obligation" of a United States person for purposes of Section 956:

We believe that a proper interpretation of the statute is reached when one focuses not on the highly technical meaning of the term "pledge" and "guarantor" as used in commercial transactions, but instead on the purpose of section 956 of the Code. Legislative history indicates that section 956 was intended to prevent a United States shareholder from being able to repatriate directly or indirectly the controlled foreign corporation's earnings without the United States shareholder being taxed on such earnings as a dividend.

No such argument can be advanced here. Viewing the substance of the transaction, we find no evidence of a controlled foreign corporation's earnings being directly or indirectly repatriated to the U.S. Consequently, for purposes of section 956(c), the pledging of stock of [CFC B] by [US Shareholder A] as a guaranty for the repayment of a loan made to the foreign corporation may not be treated as the pledge of an obligation of a United States person so as to be considered an investment in United States property within the meaning of sections 956(a) and sections 956(c).

The IRS reaffirmed the foregoing conclusion in Tech. Adv. Mem. 8101012, in which third-party indebtedness of a CFC ("Corp E") was guaranteed by a United States shareholder of Corp E ("Corp A"). To support such third-party indebtedness, a related CFC ("Corp C") agreed to subordinate an intercompany debt owed by Corp E to Corp C to such third-party indebtedness and to defer payments of interest and exchange gains in respect of such intercompany debt until such third-party indebtedness was repaid. The IRS concluded that Corp A's guarantee of the third-party indebtedness of Corp E was not an "obligation" of a United States person for purposes of Section 956 and, therefore, that the credit support provided by Corp C in respect of such third-party indebtedness did not raise Section 956 concerns.

The Regulations provide that, for purposes of Section 956, an "obligation" generally includes "any bond, note, debenture, certificate, bill receivable, account receivable, note receivable, open account, or other indebtedness, whether or not issued at a discount and whether or not bearing interest."35 While the foregoing language can (and should) be read as limiting an "obligation" to a primary indebtedness, the Regulations are silent on this point. This silence has led to some uncertainty, particularly because debt-financing documents generally define an "obligation" (for commercial law purposes) to include a guarantee obligation as well as a primary debt obligation. Some borrower groups seek to address this uncertainty by prohibiting their CFCs from guaranteeing (or having more than 65% of their voting equity pledged to secure) any "obligations" of US affiliates (including guarantees by such US affiliates of third-party indebtedness of the CFCs), which prohibition may cause confusion and frustrate the commercial expectations of the parties — could such a prohibition vitiate a CFC's guarantee of the third-party indebtedness of another CFC (and the related pledge of 100% of the guarantor CFC's equity) if such third-party indebtedness were also guaranteed by a US affiliate?

Precedential guidance affirming the conclusion reached in the Technical Advice Memoranda would provide definitive comfort on this issue.

E. CAMs/DAMs

A CAM/DAM (collectively a "CAM") should not raise Section 956 concerns.

A CAM is an agreement requiring lenders with respect to different tranches of loans to two or more related borrowers, upon a default by such borrowers, to exchange interests in the respective tranches of loans36 such that each lender ends up owning a uniform percentage of each tranche. CAMs are designed to ensure that, upon a default, each lender receives the same proportionate aggregate recovery with respect to all of the loans outstanding at the time of the default, regardless of each lender's relative ownership of each tranche prior to the default.

The need for a CAM typically will arise if (i) two or more tranches of loans to related borrowers have different priorities, guarantees, collateral or other commercial terms that would impact the expected recovery by lenders upon a default and (ii) each tranche is not owned by the same lenders in the same proportions. This fact pattern is very common in debt facilities for multinational groups that have borrowings in both the United States and non-US jurisdictions.

Two or more tranches of loans to related borrowers may have different commercial terms for a variety of tax and non-tax reasons, including as a result of Section 956. As discussed earlier in this report, due to Section 956 concerns, a third-party loan to a US borrower typically will have a different guarantee and collateral package than will a third-party loan to an affiliated non-US borrower. The loan to the US borrower may be supported by guarantees from all of the US affiliates of the US borrower and pledges of all of the assets of the US borrower and its US affiliates, other than any stock of a CFC (the pledge of which generally will limited to 65% of the outstanding voting stock and 100% of any non-voting stock of the CFC)), but may not be supported by guarantees from, or pledges of assets of, CFCs. In contrast, subject to the risk discussed above in section III.D of this report (with respect to guarantees of loans to CFCs by their US affiliates), the loan to the affiliated non-US borrower may be supported by guarantees and asset pledges from both US and non-US affiliates.

Similarly, two or more tranches of loans to related borrowers may be held by different groups of lenders (or by the same lenders in different proportions) for a variety of tax and non-tax reasons, including regulatory constraints, currency impacts and withholding tax considerations.

There is some uncertainty as to whether Section 956 could apply to a CAM involving a tranche of loans to a US borrower (a "US tranche") and a tranche of loans to a related CFC (a "CFC tranche"). The potential concern is that, because a lender to the US borrower would, upon a default of the borrowers, exchange a portion of the US tranche loans for a portion of the CFC tranche loans, the CFC borrower (and any other CFC guaranteeing the CFC tranche loans) might be viewed as providing credit support with respect to the US tranche loans.

We believe that the foregoing concern is unfounded and a CAM involving a US tranche and a CFC tranche should not raise Section 956 concerns. A CAM does not enhance the credit support with respect to the US tranche, but simply reallocates the ownership of the US tranche (and the ownership of the CFC tranche) such that each tranche is owned by the same lenders in the same proportions.

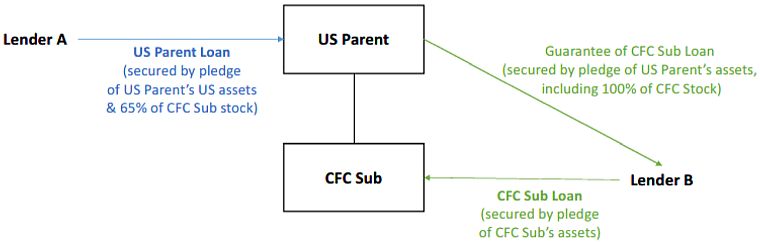

Consider the following scenario. A US corporation ("US Parent") conducts a US business and directly owns 100% of the outstanding stock of a CFC that operates a non-US business ("CFC Sub"). CFC Sub has one class of stock outstanding. US Parent obtains a $100x term loan from Lender A (the "US Parent Loan"), which loan is secured by all of the assets of US Parent other than the stock of CFC Sub and by 65% of the stock of CFC Sub. CFC Sub does not guarantee the US Parent Loan or pledge any assets in support thereof. CFC Sub obtains a $100x term loan from Lender B (the "CFC Sub Loan"), which loan is secured by all of the assets of CFC Sub. US Parent guarantees the CFC Sub Loan and pledges all of the assets of US Parent (including 100% of the stock of CFC Sub) in respect of such guarantee. US Parent's guarantee of the CFC Sub Loan (and the pledge of the assets of US Parent in support thereof) are pari passu with the US Parent Loan (and the pledge of the assets of US Parent in support thereof).

Assume that, at some later date when the full balance of both loans remains outstanding, US Parent's US business becomes worthless, but CFC Sub's non-US business has performed reasonably well. CFC Sub has the cash and/or borrowing capacity to repay the CFC Sub Loan, and value of the stock of CFC Sub is $50x. US Parent defaults on the US Parent Loan, which triggers a cross-default with respect to the CFC Sub Loan. Both loans are accelerated and become immediately due and payable.

Absent a CAM, (a) Lender B would receive a full repayment of the CFC Sub Loan ($100x) and (b) Lender A's recovery in respect of the US Parent Loan would be limited to 65% of the stock of CFC Sub (with a value of $32.5x (i.e., 65% x $50x)) and, subject to pari passu unsecured claims of competing creditors (such as trade creditors or potential tort creditors), the remaining 35% of the stock of CFC Sub (with a value of $17.5x (i.e., 35% x $50x)).

With a CAM, the recovery in respect of each loan would be exactly the same as it would be absent a CAM, but the full repayment in respect of the CFC Sub Loan and the limited recovery in respect of the US Parent Loan would be shared equally by the lenders.

A CAM does not enhance the lenders' recovery in respect of the US Parent Loan but simply places the lenders in the same economic position as if each lender owned one-half of each loan. Each lender could have funded (and held) one half of each loan without raising any Section 956 concerns. The result should be no different if the lenders' pro rata ownership of each loan results from a CAM.

Accordingly, we recommend it be confirmed that, under current law, a CAM involving a US tranche and a CFC tranche does not raise Section 956 concerns.

Footnotes

1 The principal authors of this report are Craig Horowitz and Ann Kato Creed, with research assistance from Niechao Bai. Helpful comments were received from Kim Blanchard, Bora Bozkurt, Andy Braiterman, Robert Cassanos, Josh Goldstein, Ed Gonzalez, Adam Kool, Jiyeon Lee-Lim, John Lutz, John Narducci, Richard Nugent, Arvind Ravichandran, Gary Scanlon, Michael Schler, Eric Sloan, Wade Sutton, Linda Swartz and Libin Zhang. This report reflects solely the views of the Tax Section of the New York State Bar Association ("NYSBA") and not those of the NYSBA Executive Committee or House of Delegates.

2 Unless otherwise indicated, all "Section" references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the "Code"), and all "Treas. Reg. §" references are to the Treasury Regulations promulgated thereunder (the "Regulations").

3 For purposes of Section 956, a "United States person" generally has the meaning assigned to it by Section 7701(a)(30), and includes a domestic partnership or corporation. See Section 957(c).

4 In general, a non-US corporation will be considered a CFC with respect to any taxable year of such corporation if more than 50% of (1) the total combined voting power of all classes of stock of such corporation entitled to vote, or (2) the total value of the stock of such corporation, is owned actually or constructively (in accordance with Sections 958(a) or (b)) by United States shareholders (as defined below) on any day during such taxable year. See Section 957(a). A more stringent 25% rule applies with respect to non-US corporations that derive insurance income. See Section 957(b).

5 Pub. L. No. 115-97, 131 Stat. 2054 (2017).

6 In general, a United States person will be considered a United States shareholder with respect to a non-US corporation if such person owns (actually or constructively (in accordance with Sections 958(a) or (b))) 10% or more of the total combined voting power of all classes of stock of such corporation entitled to vote or 10% or more of the total value of shares of all classes of stock of such corporation. See Section 951(b).

7 See Section 951(a)(1)(B) and Treas. Reg. §1.951-1(a).

8 See Sections 956(a) and (b).

9 See Sections 956(c)(1)(C) and 956(c)(2)(F) (United States property held by a CFC generally includes any debt obligation of any United States person other than a US corporation that is not a United States shareholder of such CFC and is not owned (actually or constructively (in accordance with Sections 958(a) or (b))) 25% or more (by voting power), in the aggregate, by United States shareholders of such CFC.

10 Treas. Reg. §1.956-2(c)(2).

11 Id.

12 While the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule would permit a pledge of just less than 66⅔% of the voting stock of CFCs (e.g., 66½%), market practice generally limits the pledge percentage to 65%. Adherence to the 66⅔% pledge limitation generally is required (to avoid running afoul of the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule) because debt-financing documents generally subject a CFC owned by a US borrower to negative covenants that limit the CFC's ability to dispose of assets and incur liabilities.

13 See Section 951A.

14 See Section 951A(b), which limits the application of the GILTI provisions to the excess, if any, of a United States shareholder's net CFC tested income for the applicable taxable year over the shareholder's net deemed tangible income return for the year, and Section 951A(c)(2)(A), which excludes several categories of income from tested income.

15 See Treas. Reg. §1.956-1(a)(2), which reduces a potential deemed dividend under Section 956 by the amount of the deduction that would be allowed under Section 245A if, in lieu of the deemed dividend, there were an actual dividend of an equivalent amount.

16 See Sections 245A(a) and 245A(b)(1). Even if an individual were to elect under Section 962 to be taxed as a corporation with respect to his or her income inclusions under Section 951(a) (including Section 956 inclusions), Section 245A would remain unavailable to the individual. See Preamble to Proposed Section 956 Regulations, REG-114540-18, 83 Fed. Reg. 55324 at 55326 (Nov. 5, 2018).

17 See Sections 245A(a), 245A(c) and 245(a)(5) (Section 245A does not apply to undistributed CFC earnings attributable to income effectively connected with a US trade or business ("ECI") and subject to US federal income tax or to dividends received by the CFC from 80%-or-greater-owned US subsidiaries).

18 For example, there is uncertainty regarding the extent to which a "nimble dividend" (i.e., a dividend paid by a corporation with current earnings and profits and an accumulated earnings and profits deficit) may qualify for the Section 245A deduction. See Preamble to the Final Section 245A Regulations, T.D. 9909, 85 Fed. Reg. 53068 at 53073 (Aug. 27, 2020) ("The Treasury Department and the IRS are studying the extent to which nimble dividends should qualify for the section 245A deduction generally and may address this issue in future guidance under section 245A."). There is also some technical uncertainty as to whether, as drafted, the "foreign source" limitation works as intended. See NYSBA Tax Section Report No. 1404, Report on Section 245A (Oct. 25, 2018), at 44–45 (requesting clarification that the foreign-source portion of a dividend from a specified 10% owned foreign corporation includes earnings attributable to all US-source income of such corporation other than ECI and dividends from 80% or greater owned US subsidiaries, as well as ECI that is exempt from US federal income taxation pursuant to an applicable income tax treaty).

19 If a CFC Debt were guaranteed by another CFC (a "guarantor CFC"), a pledge of the CFC Debt in support of the indebtedness of a US borrower might appropriately be viewed for Section 956 purposes as an indirect guarantee of the US indebtedness by the guarantor CFC. If that were the case, even if there were no guarantee of a CFC Debt, the Indirect Pledge or Guarantee Rule could apply if 66⅔% or more of the voting stock of another CFC were pledged in support of the CFC Debt.

20 In determining whether a transaction constitutes a sale of "all or substantially all" of a company's assets, New York corporate law requires a case-by-case analysis of all relevant facts and circumstances. See, e.g., Sharon Steel Corp. v. Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A., 691 F.2d 1039, 1049 (2d Cir. 1982) ("The words 'substantially all' . . . have been given meaning in light of the particular context and evident purpose of the relevant provision.") and HFTP Investments, L.L.C. v. Grupo TMM, S.A., No. 602925/2003, Trial Order, 2004 WL 5641710 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Jun. 4, 2004) (taking a two-pronged approach analyzing both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the sale in question, and citing Sharon Steel Corp.). A similar analysis applies under Delaware corporate law. See, e.g., Gimbel v. Signal Cos., Inc. 316 A.2d 599, 606 (Del. Ch. 1974), aff'd, 316 A.2d 619 (Del. Sup. Ct. 1974) (looking to whether there has been a sale of "assets quantitatively vital to the operation of the corporation that is out of the ordinary and that substantially affects the existence of the corporation") and Altieri v. Alexy, No. 2021-0946-KSJM, 2023 De Ch Lexis 126 (Del. Ch. 2023) (citing Gimbel).

21 A CFC Holdco is typically designated a "Restricted Subsidiary" under the applicable debt-financing documents and thereby subject to negative covenants that restrict its activities to a meaningful degree. However, these restrictions typically do not limit the activities of the CFC Holdco to any greater extent than such restrictions limit the activities of the US borrower or other Restricted Subsidiaries.

22 As discussed above in section III.A of this report, we believe that pledges of CFC Debt should not raise Section 956 concerns. Accordingly, the ownership of CFC Debt by a CFC Holdco or similar entity should not raise Section 956 concerns.

23 The proper treatment of pledges of the equity of, and guarantees provided by, disregarded entities that own a CFC is addressed more broadly below in section III.C of this report.

24 In section III.B above, this report discusses the proper Section 956 treatment of CFC Holdcos.

25 Lenders often seek a pledge of the equity of a guarantor (in addition to obtaining the guarantee and a pledge of the guarantor's assets) because, in the event of a default, lenders may enhance their recovery by foreclosing on the equity pledge (in lieu of foreclosing on the guarantor's assets), thereby leaving the guarantor's operations intact (and preserving going concern value).

26 See, e.g., Rev. Rul. 99-5, 1999-1 C.B. 434 (Jan. 15, 1999).

27 A deemed pledge of 5% of the 35% of the CFC stock not actually pledged would be a deemed pledge of 1.75% (i.e., 5% x 35%) of the CFC stock, which, when added to the actual pledge of 65% of such stock, would exceed 66⅔% of such stock.

28 See Priv. Ltr. Rul. 202337007 (Oct. 3, 2022); Priv. Ltr. Rul. 201010015 (Mar. 12, 2010); Priv. Ltr. Rul. 200630002 (Jul. 8, 2006); and Priv. Ltr. Rul. 200315001 (Apr. 11, 2003). A fifth PLR involving similar facts (Priv. Ltr. Rul. 200709013 (Mar. 2, 2007)), does not meaningfully inform the analysis here because the successor disregarded entity promptly became a partnership as part of an integrated plan.

29 In each case, the change in obligor did not result in a significant modification because one of the exceptions in Treas. Reg. §1.1001-3(e)(4)(i) applied.

30 The IRS has treated disregarded entities differently

in some other contexts where doing so better reflected the purpose

of the particular statutory or regulatory provision at issue. But

we believe that those authorities emphasize the commercial

realities of the particular situation, as opposed to a literal

adherence to the tax fiction of a disregarded entity, and are not

inconsistent with the PLRs addressing the Debt Modification

Regulations or our recommendation with respect to Section

956.

For example, two PLRs concluded that indebtedness of a disregarded

entity should be treated as nonrecourse indebtedness of the

regarded owner (as opposed to recourse indebtedness of the

disregarded entity) for purposes of determining whether the

satisfaction of such indebtedness at a discount resulted in gain

(pursuant to Commissioner v.

Tufts, 461 U.S. 300 (1983)) or CODI.

See Priv. Ltr. Rul. 201644018 (Oct. 28, 2016) and

Priv. Ltr. Rul. 202250014 (Dec. 11, 2020).

In Priv. Ltr. Rul. 200953005 (Jan. 4, 2010), the IRS concluded

that, for purposes of Sections 108(a)(1)(D) and 108(c)(3)(A) (which

permit a non-corporate taxpayer to exclude from gross income any

CODI arising with respect to "qualified real property business

indebtedness" ("QRPBI")), indebtedness secured only

by the equity interests of disregarded entities that owned real

estate should be treated as "secured by" such real estate

(and thereby as QRPBI). While the PLR stated that it would be

"incongruent" to give significance to the disregarded

LLCs for the purpose noted above but to disregard such LLCs for all

other purposes, the focus of the analysis appears to be on

furthering the specific purpose of the QRPBI provisions

(i.e., to provide relief from CODI arising from a decline

in the value of real estate used in a business). The PLR explicitly

concludes that, while a pledge of the equity interests of the

entities owning the real estate in question was not a mortgage

(i.e., an actual pledge of the real estate), the

legislative history of the QRPBI provisions evidenced a legislative

intent to include a "broader range of security interests"

than just mortgages. Moreover, the PLR emphasized that the

indebtedness in question was effectively secured by the real estate

as an economic matter because the only assets owned by the

disregarded entities were the real estate and related personal

property ("[T]he only difference between this structure and

that of a mortgage or deed of trust is the method of

foreclosure.").

The IRS reached a similar conclusion in Rev. Proc. 2003-65, 2003-2

C.B. 336 (July 11, 2003), which provided a safe harbor for treating

a loan made to the owner(s) of a partnership or disregarded entity

owning real property, and secured only by the equity interests of

the partnership or disregarded entity, as an obligation secured by

a mortgage on real property or an interest in real property (and

thereby as a real estate asset generating qualifying REIT gross

income for purposes of Section 856(c)(3)).

31 Our recommendation is not intended to permit a CFC to effectively guarantee a primary debt obligation of a United States person (a "primary US debt") without adverse Section 956 consequences by guaranteeing a US guarantee of the primary US debt (rather than directly guaranteeing the primary US debt). The CFC's guarantee of the US guarantee should be viewed as an indirect guarantee of the primary US debt.

32 See Tech. Adv. Mem. 8042001 (Mar. 18, 1980) and Tech. Adv. Mem. 8101012 (Oct. 7, 1980).

33 See Sections 6110(b)(1)(A) and (k)(3) (technical advice memoranda generally may not be used or cited as precedent).

34 See S. Rep. No. 94-938, at 225-226 (1976).

35 Treas. Reg. §1.956-2(d)(2).

36 For commercial reasons, the exchanges typically are implemented by issuing economic participations in the underlying loans, as opposed to actual assignments of the loans.

Originally published inTax Notes, 13 December 2024

To subscribe to Cahill Publications Click Here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.