- within Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

- in United States

- within Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

- in United States

- within Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

- with Finance and Tax Executives

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy and Insurance industries

INTRODUCTION

U.S. real estate remains a favored asset class for foreign investment by Israeli residents. With the Israeli shekel currently being relatively strong against the U.S. dollar, investments in the U.S. have become even more attractive. And while personal use property in cities like Miami and New York City remain a privilege of high net worth individuals, fractional investments in multifamily residential and commercial property have become available to many investors.

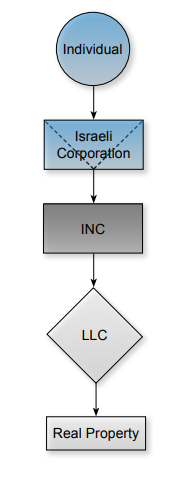

Many entrepreneurs are active in the field and offer "friends and family" to participate with as little as a $50,000 investment. Typically, there is an Israeli living in the U.S. who forms a limited liability company ("L.L.C.") that is formed to invest in a certain property, with that individual as the manager, and the investors participate as members of the L.L.C.

Often, the entrepreneur shows the investors the expected yield of return, but may fail to mention the risk of U.S. estate tax. Some investors believe that because they do not own the real estate directly, they will not face the exposure, and hope that the manager of the L.L.C. will simply transfer their interest in the L.L.C. to their heirs. They assume that since no deed recording will be needed, the issue will not come up. Not only is that not the law and not recommended by any competent U.S. tax adviser, but also, it is good to remind those investors that their plan only works if the L.L.C. manager agrees to be noncompliant with U.S. tax law, and that hardly seems an appropriate plan.

Those who realize the risk and want to plan, soon realize that a "perfect" structure may not exist when trying to be compliant in both the U.S. and Israel. Also, at times, after several years of successfully investing in the U.S. with the same entrepreneur, the investor may be invited to the table, and becomes more involved. It may be by way of organizing others to invest, or by advising or otherwise assisting the entrepreneur in relation to the investments, financing, etc. Even if not compensated, this involvement may affect the tax treatment of the L.L.C. Additionally, if the compensation is structured differently than added profit share, it may complicate the tax position of the investor.

This article tackles the key challenges and offers possible structures for Israeli investors to consider in order to optimize their U.S. real estate investments.

DIRECT OWNERSHIP + SPLITTING THE INVESTMENT BETWEEN DEBT AND EQUITY

This assumes an equity investment in the L.L.C. as well as execution of a debt instrument by the L.L.C. to the same investor, which is introduced as a partial protection from estate tax. While the loan must not be participating, and therefore limits the upside, and the investment in equity must grant the investor less than 10% of the capital and profits in the L.L.C., the benefit of such bifurcation is that as long as the debt qualifies as "portfolio debt," it will not be subject to U.S. estate tax. The equity investment remains exposed to estate tax if the investors total investment in all U.S. situs assets is valued at more than $60,000 at death.

From a U.S. perspective, the Israeli investor is a member of an L.L.C. and is expected to receive a Schedule K-1 annually from the L.L.C. That is the I.R.S. form that will report his or her share of the income, deductions, etc. The investor is required to file a U.S. tax return annually based on the L.L.C. results shown on the Schedule K-1. To do that, the investor must obtain a tax I.D. The investor will pay U.S. income tax on the net rental income, typically through quarterly withholding taxes paid by the L.L.C., as well as on the profit from the ultimate sale of the property, in the manner set forth in the L.L.C. agreement, often in proportion to such investor's equity in the L.L.C. This profit is also subject to withholding. The collection of withholding taxes, on quarterly basis and upon sale, does not excuse a non-U.S. member of the L.L.C. from his or her U.S. tax return filing obligation. Rental income is taxed as ordinary income, at graduated rates up to 37% Federally for an individual taxpayer. State and local tax may also apply. After depreciation deduction is claimed, as well as other expenses such as real estate taxes and insurance, often there in no taxable income for the duration of the investment, which typically is between three and seven years. Capital gain is taxed to individuals at up to 20% Federally (state and local tax may also apply), but any gain measured by the reduced basis attributable to depreciation deductions claimed over the years is taxed at 25% Federally.

Most, if not all, investors assume that the amount received from the L.L.C.'s sale of property will be treated as capital gain, which is taxed favorably in the U.S. (either at 20% or 25% as mentioned above). However, if the L.L.C. is engaged in a U.S. trade or business, and the sale of the property is attributable to such trade or business, (for example, construction and sale of units in a condominium building), the profit may be taxed as ordinary income rather than capital gain, even if the investor is a passive investor. This is because the character of the income and profit earned by an L.L.C. is determined at the L.L.C. level and if the L.L.C. is engaged in building units that are for sale to customers in the ordinary course of business, all profits are treated as business income.

Even when the property is held for rental, any plan that contemplates a sale of the rental structure from the outset may lose its character as property held for investment and rental business and may convert the treatment of the sale proceeds from capital gains to ordinary business income. The risk often arises because the manager of the project has a history of "build and flip." Just because an L.L.C. has rental income does not necessarily mean the L.L.C. is solely engaged in the rental business. Being so engaged will not "ruin" the capital gain nature of the profit. When the purpose of the investment is "buy to sell," a risk exists that the gain that is recognized by the L.L.C. may not qualify for favorable capital gain treatment.

Even when the property is held for rental, any plan that contemplates a sale of the rental structure from the outset may lose its character as property held for use in the rental business. The risk often arises because the manager of the project has a history of "build and flip." Just because an L.L.C. has rental income does not necessarily mean the L.L.C. is solely engaged in the rental business. Hence a risk exists that the gain that is recognized by the L.L.C. may not qualify for favorable capital gain treatment.

The rules under the Foreign Investment in Real Property Act ("F.I.R.P.T.A.") will apply to the equity investment portion only. This will result in withholding with respect to the disposition of the underlying property by the L.L.C. as well the sale of the L.L.C. interest itself. Additionally, since an L.L.C. is generally taxed as a partnership, the regular withholding rules applicable to U.S. partnerships having foreign partners will also apply. As a result, these withholding rules may at times compete with the F.I.R.P.T.A. withholding rules, and regulations prevent double withholding and address which of the rules prevail in the circumstances of the L.L.C. and its business.

As long as the "portfolio indebtedness" requirements are met (which is required in order for the instrument to be exempt from U.S. estate tax), the interest paid on this instrument will not be subject to U.S. income tax.

Advantages

Direct ownership is simple and avoids complex entity structures. Due to the L.L.C. being used, some confidentiality for the investor remains, subject to other member-investors' visibility. Bifurcating the investment and using debt reduces the amount of value exposed to U.S. estate tax.

Challenges

For the debt portion to qualify as "portfolio debt," the investor cannot be viewed as the owner of 10% or more of the equity in the L.L.C. and the interest payments cannot be contingent on profits. The challenge therefore is to manage the risks. One principal risk involves the application of the attribution rules. These rules cause an individual to be considered to own the L.L.C. interest of another member. This may occur when family members invest in the L.L.C.

Subject to a $60,000 exemption, the equity portion is exposed to U.S. estate taxes. Estate taxes are levied at rates of up to 40%. Term life insurance can be purchased to protect against such exposure, if the investor is insurable. Annual filing may be burdensome, and withholding often results in excess tax paid and can affect cashflow.

The Israeli Aspect

Israel generally treats the L.L.C. as an opaque entity. Initially, an investor can notify the tax authorities if he or she wishes to treat it as a passthrough, however even if such election is made, the L.L.C. is a passthrough only for certain purposes.

An opaque L.L.C. raises a risk of "management and control" existing in Israel, which would subject the L.L.C. to corporate tax levels in Israel in addition to the U.S. Double taxation is a distinct possibility. Management and control can be a risk if the entrepreneur who manages the L.L.C. lives in Israel, a fact that can change during the life of an investment, or if the investors that were invited to the table get involved in decision making. In any event, since the U.S. has the undisputable first right to tax when U.S. real property is the asset held by the L.L.C., and because Israel will recognize the U.S. taxes paid by the investor as paid by the L.L.C., the exposure to double taxation for the L.L.C. is practically eliminated and typically concludes with the added couple of points of tax due to Israel.

However, for the investor, the situation is different, and an opaque treatment for the L.L.C. may result in significant double taxation. This is because the U.S. tax paid by the investor will not be creditable in Israel for the investor. When a distribution is made, Israel will tax the investor again for what it views as dividend income, currently taxed at 25% up to a not-so-high certain threshold and 30% thereafter.

n comparison, if an election for passthrough treatment in Israel is made with regard to the L.L.C., the situation is better, because the U.S. tax paid is creditable, and capital gain treatment (to extent available) flows through. As a result, upon a sale, the investor will pay 20% Federal tax, as well as potentially some State tax, and both those taxes will be creditable against the Israeli tax of 25% - 30%, resulting in potentially little or no additional Israeli tax.

With respect to rental income, this is generally taxed as business income in Israel when it flows through from an L.L.C. Therefore, the income would be taxed at graduated rates of up to 50% with credit for any U.S. tax paid.

The drawback of the L.L.C. – even if an Israeli tax election is in place – is the fact that it is only partially tax transparent, meaning, losses do not flow through. Therefore, if an investor invests in more than one L.L.C. at the same time, and one produces losses but the other gains, Israel will not allow an individual to pool the results of the several L.L.C.'s. Tax will be due in Israel with respect to the profitable L.L.C.'s without any offset for the losses of other L.L.C.'s. For that reason, Israelis who invest in more than one L.L.C. generally prefer the use of U.S. partnerships over L.L.C.'s, because Israel recognizes foreign partnerships as true tax transparent entities.

Lastly, Israel does not allow local tax to be credited. Consequently, New York State tax will be creditable, but New York City tax will not.

OWNERSHIP THROUGH A TWO-TIER CORPORATE STRUCTURE WHERE THE UPPER TIER ENTITY IS AN ISRAELI "FAMILY COMPANY"

In General

When investors recognize that their U.S. profits will be taxed as ordinary income because the real estate investment is made in a development project, they often consider using a U.S. corporation. This is because the U.S. corporate tax rate is relatively low, 21% at the Federal level. This compares to rates of up to 37% when individuals are involved. In addition, State and Local taxes will apply to both individuals and corporations and the differences in individual and corporate tax rates generally often are not of the same magnitude. Dividend distributions from the U.S. will be taxed at the rate of 25% under the terms of the existing Israel-U.S. Income Tax Treaty (the "Treaty") if the shareholder is an Israeli resident individual, but only at a 12.5% rate if the shareholder is an Israeli corporation owning least 10% of the U.S. corporation. The two levels of tax result in approximately 40% Federal taxes in the U.S. if the individual rate is taken into account.

When the Israeli company used as the upper-tier entity is a Family Company, discussed more in detail below, the U.S. will apply the Treaty in a way that recognizes the Israeli look through treatment and essentially grant the Treaty benefits to the individual, thus subjecting the dividend to a 25% tax. If a regular Israeli company is used, the total effective rate of U.S. Federal tax may be lower, approximately 30% (only 12.5% will be imposed on the after tax earnings). However, Israel will tax dividends paid by the Israeli company at a rate that varies between 25% and 30%. Consequently, a Family Company is most often used.

An additional U.S. tax benefit that is derived from the use of an upper-tier corporation is that it protects the ultimate beneficial owner from U.S. estate tax on his share of the value of the U.S. corporation. Ownership of a U.S. corporation by an Israeli resident individual is subject to the same exposure to estate tax as direct ownership of U.S. real property.

Because the owner of the real estate is a U.S. corporation, no F.I.R.P.T.A. tax is imposed on the gain derived from the disposition of the underlying property. In addition, no branch profits tax ("B.P.T.") applies to the Israeli company in connection with the sale of shares of a U.S. corporation. B.P.T. is discussed in more details below where investment through an Israeli corporation is discussed.

Advantages

If the project is structured to generate ordinary income for an Israeli investor, it may be preferable to have the U.S. tax imposed at lower corporate rates, and to have the U.S. corporation reinvest the after-tax excess cash in additional real estate projects in the U.S. Additionally, if several investments are made, it is possible to offset income in one project with losses in a second project within the U.S. corporation.

Additionally, the investor is able to control the timing of the dividend from the U.S. corporation, which may allow some deferral in both the U.S. and Israel. Lastly, neither the individual nor the Israeli company need to file U.S. tax returns.

Challenges

This structure may be viewed as complex and may have added administrative costs relating to filing. It typically would be considered by investors who invest significant funds in development properties.

To view the full article click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.