- with Finance and Tax Executives and Inhouse Counsel

- in United States

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit, Insurance and Technology industries

What is ADM?

Automated decision-making (ADM) refers to the use of technology to make decisions with limited or no human intervention. ADM systems range in complexity and functionality – from traditional rule-based systems (eg, fixed-criteria loan approval processes) to more advanced models powered by complex algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI).

While ADM has existed, and been used by many companies, for decades in simpler rule-based forms, it is now receiving heightened attention due to the growing scale and sophistication of AI technologies and their ability to support ADM. As advanced ADM is increasingly embedded into critical functions across industry and government, governance and risk management frameworks will have to evolve in step.

This article looks at the lifecycle of ADM, mapping key considerations from data governance and algorithmic integrity to risk assessments and contractual frameworks. We explore how organisations can proactively assess their ADM frameworks to ensure transparency, mitigate risks, and uphold ethical decision-making principles ahead of the next tranche of privacy reforms and anticipated AI regulation.

Current legal landscape

Privacy reforms – where are we and what's coming?

Australia's privacy framework is undergoing significant reform, which is being implemented in two legislative tranches. The reform agenda includes new provisions addressing privacy implications of ADM – specifically:

- Tranche 1 of the privacy reforms (implemented on 10 December

2024)1 introduces a requirement for privacy policies to

include key details regarding ADM use. We set out further

information on this below.

This transparency obligation does not come into effect until 10 December 2026. The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has indicated its intention to publish more specific regulatory guidance on the topic in 2026. - Tranche 2 of the privacy reforms is expected to contain a more

sweeping set of changes than tranche 1. While details of these

reforms are yet to be released, the Australian Government

(Government) has indicated its support to introduce:2

- a right for individuals to request meaningful information about how automated decisions with significant effect are made; and

- a requirement for organisations to conduct privacy impact assessments for high-risk activities (potentially covering ADM activities).

For further information on the privacy reforms, see our previous article here: Navigating Australian Privacy Reform: Your guide to the changes ahead.

AI regulation

As noted above, AI often supports or enables ADM solutions. Last year the Government consulted on a proposal to introduce mandatory guardrails for AI in high risk settings3 – and ADM that impacts on the rights of individuals or their ability to access services would likely fall into that high risk category. However, the Government has recently announced the National AI Plan5 which steered clear of standalone AI legislation, instead confirming that the Government's regulatory approach to AI "will continue to build on Australia's robust existing legal and regulatory frameworks", in addition to other voluntary frameworks and guidance. This regulatory approach will be supported by a newly established AI Safety Institute and could have direct or indirect implications for ADM.

In September 2024, the Government released a set of Voluntary AI Safety Standards (VAISS), which provide guidance on good practices for the safe and responsible development and use of AI (including ADM that leverages AI). The ten key principles set out in the VAISS will assist organisations to manage risks in using AI for the purpose of ADM. In October 2025, the Government published their 'Guidance for AI Adoption' (GfAA).6 The GfAA condenses and integrates the original ten principles into six practices for responsible AI adoption. It is likely to be beneficial for organisations to adopt these practices early in the roll-out of ADM to build-up organisational knowledge and governance in managing these risks.

As mentioned above, we may also start to see current laws evolve to address AI or ADM specific risks. For example, a bill5 has recently been introduced in NSW to amend the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW) and establishes a specific duty for organisations to ensure that digital work systems – broadly defined to include algorithms, AI, automation, online platforms and software6 – do not create health and safety risks for workers, such as through unfair workload allocation or discriminatory practices7. These reforms reflect growing recognition that ADM and algorithmic management can introduce new psychosocial and physical risks8, and require proactive governance in system design and deployment.

International comparison

ADM is subject to more stringent regulation in some jurisdictions outside Australia than what is proposed in the upcoming Australian privacy reforms. For example, since it was introduced in 2018, Article 22 of the European Union (EU) General Protection Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes comprehensive obligations on organisations engaging in ADM. A number of data privacy regimes in other jurisdictions are also following suit with similar provisions.

Article 22 of the GDPR completely restricts the use of solely automated decisions (ie, those that are made without any human intervention) that produce legal or similarly significant effects for individuals, unless one or more of the specific conditions set out in Article 22 apply (eg, where conducting the ADM is a contractual necessity or if explicit consent has been obtained from affected individuals).

Where such ADM is permitted, the GDPR requires organisations to

implement safeguards to protect individuals' rights and

freedoms. These include providing meaningful information to

affected individuals about the decision-making logic and offering

individuals the opportunity to challenge and seek review of the

decision or request human intervention.

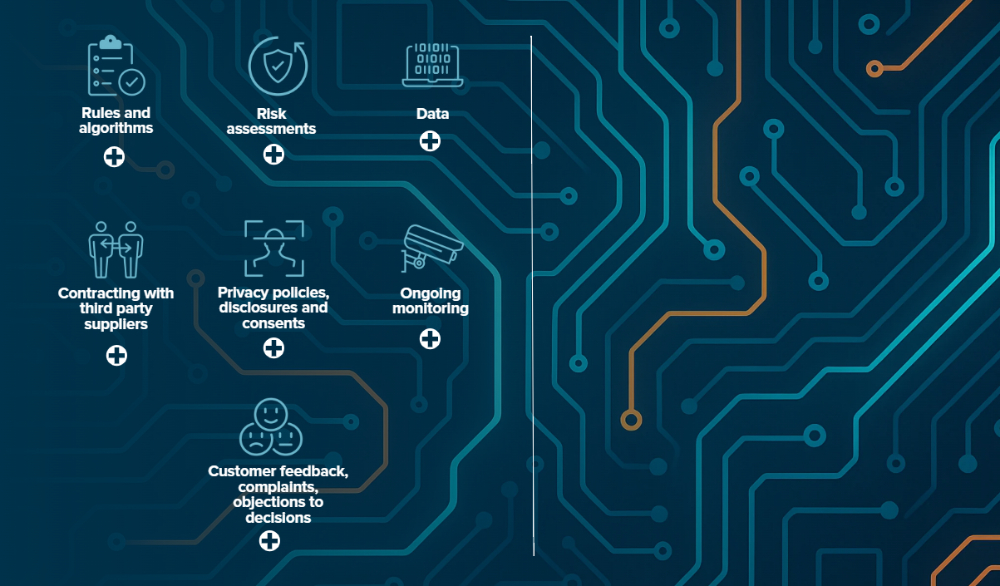

Lifecycle of ADM

Rules and algorithms

There has been significant legislative and regulatory scrutiny

(particularly in the context of consumer-facing digital platforms)

over the risks and potential harms posed by algorithms and ADM.

From a legal perspective, key risks include:

Algorithmic bias, which can result in unlawful discrimination or unfair treatment.

Algorithms that operate without sufficient safeguards against bias, discrimination or unfair treatment may infringe federal and state anti-discrimination laws, which prohibit discrimination based on various protected attributes (eg, age, disability, race, sex, gender and others) in certain contexts, as well as Australia's international human rights obligations.

These risks can be heightened when ADM is used to predict or determine access to critical services, such as credit approval, employment opportunities, healthcare, insurance or access to justice or redress mechanisms.

One notable example is the 'Robodebt Scheme' (described further below), which used an algorithm to match welfare recipients' reported income with annual income data from the ATO to identify overpayments and automatically raise debts. However, the algorithm was flawed in that it did not account for the reality of irregular, casual or part-time work which had a disproportionate impact on vulnerable groups such as people on low incomes or those with unstable work.

Consumer harms such as misleading or deceptive conduct and others.

Organisations must have a clear understanding of how their ADM algorithms operate and ensure that consumers are provided with meaningful transparency, especially where algorithms are used to determine key outcomes or shape how information is presented, ranked or priced. In addition to the new transparency requirements introduced under the privacy reforms (explored further below), regulators have scrutinised the extent to which information provided to consumers about algorithmic processes accurately reflects the actual functioning of ADM systems in place.

For example, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has taken enforcement action in several high-profile cases involving algorithmically-driven goods and services.9

|

ACCC v Trivago (2020) In 2022, Trivago was ordered to pay penalties of $44.7 million after it was found to have made misleading representations about hotel room rates in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law (which is set out in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)). The misleading representations were made by, and in relation to, Trivago's comparison website for hotels. While Trivago claimed that its website would identify the cheapest rates available for a hotel room, its algorithm in fact favoured rates from booking sites that paid higher fees to Trivago with the result that those sites were promoted over others offering lower rates in 66.8% of listings. Trivago's contraventions were estimated to have caused loss or damage to Australian consumers in the order of $30 million. |

Risks arising from the 'black box' problem.

The ability to be transparent with customers and explain how automated decisions have been reached can be undermined by the 'black box' problem. For example, for certain claims under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), the burden is on the employer to prove that no unlawful bias or discrimination played a role in the action the subject of the claim.10 If organisations do not have a clear understanding of how their ADM algorithms operate, that burden may be difficult to discharge.

The 'black box' problem can also give rise to challenges in the attribution of liability. For example, when something goes wrong and harm is caused by an ADM system, should liability lie with the developer, the organisation that implemented it or someone else? Some commentators suggest that traditional torts such as negligence may not be fit for purpose in these circumstances because of difficulties identifying the foreseeable consequences of 'black box' AI models or ADM systems due to their autonomous nature and related difficulties in establishing causation.11 Even in cases where a strict liability regime applies to protect consumers from defective products, identifying the origins of a defect or error in an AI model or ADM system may be very difficult or impossible where the 'black box' problem exists.12

Potentially significant liability from breaching duties and other legal obligations flowing from governance failures in the deployment of ADM tools.

The failures of the Government's automated debt recovery scheme that used income averaging algorithms to raise debts against welfare recipients (Robodebt Scheme) highlights the serious risks of deploying opaque and flawed ADM systems at scale. Beyond the well-documented threshold issues associated with the illegality of the very rules underpinning the system, the risks that materialised included issues with the data matching as well as the lack of human review and assurance of the automated decisions that were produced. These issues make clear the need for rigorous quality assurance and human oversight mechanisms in ADM systems. Where decisions carry significant consequences, it may be appropriate to establish risk-based thresholds that trigger mandatory review to ensure that higher-risk decisions are subject to proportionate scrutiny.

The Government has agreed to pay $2.4 billion to victims of the Robodebt Scheme (including legal and administrative costs and $1.76 billion in forgiven debts).

To mitigate risks, the question is how to embed transparency,

explainability and accountability into the design and governance of

ADM models.

ADM models may be perceived as driving cost savings and

efficiencies. The flip side is that when these systems go wrong,

they can go systemically wrong. This means that any cost savings

need to be balanced with investment in diligence and understanding

how the algorithm works, including:

- Adequate testing to confirm that the algorithm works as intended, both prior to deployment and on an ongoing basis.

- Rigorous design testing and risk assessments upfront. This includes documenting decision logic, which is likely to go beyond 'chain of thought' reasoning.

- Ensuring appropriate ongoing governance and implementing structures for independent review or verification of critical ADM decision points.

Risk assessments

Safe and responsible deployment of ADM requires a structured and proactive approach to risk management. Organisations should assign clear accountability to people in relation to each element of the ADM lifecycle. Risk assessments should be conducted prior to implementing or repurposing ADM systems, particularly for high-risk use cases. For example, this may include where ADM systems make decisions which affect:

- an individual's rights under a contract, agreement or arrangement;

- an individual's access to a significant service or support, such as healthcare, insurance, housing, education or lines of credit;

- an individual's employment opportunities, including recruitment, promotion or termination; and

- a business customer's creditworthiness when applying for loans, lines of credit or trade finance.

These risks are even more acute where the decisions affect groups of potentially vulnerable individuals. Regulators have been particularly focused on ADM systems which operate unconscionably against these individuals, with significant penalties imposed.

Guidance released by the Government and regulators such as the OAIC and ASIC emphasise the need to evaluate potential harms to individuals (taking into account privacy considerations and broader community values) alongside organisational risks such as reputational damage, cybersecurity vulnerabilities and lawfulness. Where appropriate, assessments should involve cross-functional input and result in actionable strategies to mitigate or eliminate identified risks. A privacy impact assessment and a security risk assessment could be conducted together with, or as a part of, a broader risk assessment for the ADM project.

Data

The reliability and performance of ADM systems are fundamentally shaped by the quality of the input data. The risks associated with using poor quality data are well-documented, including discrimination arising from biases or inaccuracies within the dataset itself (eg historical, representation, measurement, evaluation and sampling biases) which may be replicated in outputs.

A notable instance of algorithmic bias arising from flaws in the underlying dataset is the AI-enabled recruitment tool launched by Amazon in 2014. The tool was trained on resumes submitted to Amazon over a 10-year period, and since most of the applicants in this 10-year period were male, the tool learned to favour male candidates over female candidates even though the sex of the applicants was not included in the selection information (eg, where a resume listed a candidate's role as a "women's chess club captain" or referred to an all-female college). Amazon ultimately decommissioned the tool.

Similarly, the Mobley v Workday, Inc.14 class action in the United States is one of the first major legal challenges to the use of algorithmic hiring tools. The plaintiffs allege that Workday's algorithms filtered out older candidates, often without human review, in contravention of federal discrimination laws. While still ongoing, the allegations and early rulings made in the class action suggest that organisations may face legal exposure in respect of both their own practices but also the practices of vendors providing AI tools, especially where those tools are trained on biased input data or operate without human oversight.

Assessment of data quality and the identification of historical bias is a complex area and market practice in this area is still emerging. Organisations will need to carefully consider what steps need to be taken to detect and mitigate these risks.

Beyond data quality concerns, organisations must also navigate a range of other data-related risks, including as to:

- Accuracy, de-identification and collection of personal

information. Personal information contained in input or output data

must be handled in accordance with privacy laws. Amongst

other things, organisations must take reasonable steps to ensure

that the personal information they hold is accurate, up-to-date,

complete, relevant and not misleading, having regard to the

purposes for which the information is held.

If third party datasets are used, organisations may need to understand the circumstances of the original collection of personal information (ie, data sources and compliance with privacy notice or consent requirements).

Organisations may consider de-identifying personal information prior to use in ADM systems, however whether this is appropriate will depend on what the system needs to achieve with input data at a particular stage in the process. For example, personal information may be less important to training an AI model, compared to applying the model to a particular individual.

Additionally, robust de-identification may be difficult, particularly where aggregated data is drawn from multiple datasets (which raises concerns as to potential re-identification through AI technologies).

- Data minimisation. Under the Australian

Privacy Principles (APPs) (contained in Schedule 1 of the Privacy

Act 1988 (Cth) (Privacy Act)), organisations must limit the

collection of personal information to what is reasonably necessary

and take reasonable steps to destroy or de-identify it once no

longer required. Collecting excessive data not only increases

privacy risks but also heightens exposure to cybersecurity

threats.

- Cybersecurity: Strong security measures are essential to protecting training data, output data and ADM systems from unauthorised access or manipulation. Certain organisations will also need to ensure compliance with sector specific regulation around information security, such as Prudential Standard CPS 234 for APRA regulated entities.

Where organisations use ADM systems developed or operated by third parties, it is essential to address data use rights with those third parties, including confidentiality of the data, how it can be used and what safeguards are in place.

For more information on the current debate in Australia, see our article here: Australian Productivity Commission proposes text & data mining exception to copyright infringement for AI training.

Contracting with third party suppliers

Organisations may choose to outsource the design, implementation, run and/or maintenance of ADM systems to external suppliers, rather than managing these processes internally. In such cases, it will be important that contracts with third party suppliers clearly set out responsibilities, risk allocation and oversight mechanisms across the ADM system's lifecycle.

In addition to the common areas of contention in technology and data procurement, key considerations in the ADM context include allocating roles, rights and responsibilities between the parties in respect of:

- privacy and cybersecurity controls;

- transparency, including notices and consents for individuals who will be affected by the ADM;

- governance mechanisms, including human oversight;

- management of data and know-how collected and developed during the course of the engagement, including use of such information to train or improve other ADM models or provide it to other parties;

- adversarial testing to identify any bias or other unlawful capabilities;

- third party claims, particularly in relation to IP infringements in relation to both the model and the use of any third party inputs used to train or enhance the model;

- addressing accountability for ADM outputs, including allocating responsibility for the effects of the ADM outputs and ensuring safeguards are in place to ensure compliance with applicable laws;

- capability to provide explanations for the basis on which decisions are made; and

- dispute resolution processes, including avenues for individuals to submit feedback or complaints or to contest decisions.

|

Case 634/21 SCHUFA Holding (Scoring) (2023) (Schufa) The importance of clearly defining roles and responsibilities in contracts with ADM technology suppliers is underscored by the Schufa case under the GDPR in the EU. In that case, Schufa – a third party credit rating agency –argued that it was not responsible for ADM because it merely generated a credit score, while the final decision to approve or reject loan applications was made by the bank. However, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) rejected this argument, holding that the creation of the credit score itself constituted an automated decision with significant effects under Article 22 of the GDPR. This ruling highlights that even upstream contributors to ADM processes may be directly subject to regulatory obligations in the EU. Accordingly, organisations outsourcing ADM functions should ensure that contracts explicitly address accountability for ADM outputs, including how decisions are generated, who is responsible for their effects, and what safeguards are in place to ensure compliance with applicable privacy laws. |

Privacy policies, disclosures and consents

Organisations must comply with privacy obligations relating to notice and consent when collecting, using or disclosing personal information as part of ADM processes. However, the OAIC has cautioned against overuse of notice and consent mechanisms where this places the burden of understanding the risks of complicated information handling practices on individuals. In particular, the OAIC cautions that AI tools often use personal information as the basis for a decision in a way that is 'invisible or difficult to comprehend' and is challenging for organisations to clearly explain to individuals.15

As noted above, the tranche 1 reforms to the Privacy Act will require organisations to update their privacy policies in respect of ADM (from 10 December 2026 onwards). This will be implemented through the addition of new APPs 1.7 to 1.9. In anticipation of further guidance on these new APPs from the OAIC in 2026, organisations should start preparing by seeking to understand how they use ADM currently, where this involves personal information, and what effect the ADM can have on individuals.

| Which organisations must comply? |

Any organisation that has arranged for a computer program, using personal information, to make, or do a thing that is substantially and directly related to making, a decision that could reasonably be expected to significantly affect the rights or interests of an individual. It may not be straightforward to determine whether your organisation meets the legislative threshold – this can often depend on the extent of automation of a system and level of human involvement. |

| What must be covered in the privacy policy? |

|

These transparency requirements may prompt individuals to seek further clarification regarding how their personal information is used within ADM systems. Accordingly, organisations should be prepared to respond to such inquiries with clear and accessible explanations and further information as required. While provision of this further information is not yet a positive obligation under the Privacy Act, many organisations will look to accommodate these requests as part of meeting broader transparency standards.

Penalties for breach of the Privacy Act can be significant, with the maximum penalty for a serious or repeated interference with privacy being $50 million or more.

On 8 October 2025, the Federal Court of Australia ordered the first civil penalty ($5.8 million) under the Privacy Act against Australian Clinical Labs. Refer to our article here for further details. This signals a clear shift toward stronger enforcement by regulators, moving beyond compliance notices or warnings to imposing substantial financial penalties.

Customer feedback, complaints, objections to decisions

While not currently required under Australia law, it is considered best practice for organisations to establish processes that allow individuals to understand and, where appropriate, challenge the use or outcomes of ADM systems. To this effect, the Commonwealth Ombudsman's Better Practice Guide on ADM suggests that organisations should consider publishing plain-language transparency statements that explain how ADM systems they use operate, what decisions they make and how individuals can seek review. ADM systems should also be capable of generating a 'statement of reason'19 (which typically, among other things, lists findings on material questions of fact and includes a probative assessment or weighing of evidence), of each decision, particularly where the outcome significantly affects an individual's rights or interests. This reflects leading global standards (most notably, under Article 22 of the EU GDPR) as well as Implementation Practices 2.2 and 4.2 of the GfAA, which encourages mechanisms for individuals to contest AI-driven decisions. Additionally, tranche 2 Privacy Act reforms are anticipated to introduce a right for individuals to request meaningful information about how significant automated decisions are made.

|

Case C-203/22 Dun & Bradstreet Australia (2025) The anticipated introduction of a right for individuals to request meaningful information about how significant automated decisions are made aligns with global developments, including recent case law under the GDPR. In Case C-203/22, the CJEU considered a challenge by an individual seeking to understand why their mobile phone contract application was rejected following an automated credit assessment by Dun & Bradstreet Australia (D&B), an organisation that operates in the business information and credit scoring sector. While D&B argued that disclosing the logic behind the decision would compromise its trade secrets, the Court held that while organisations are not required to disclose complex algorithms, they must provide sufficient insight into the ADM process to allow individuals to understand and contest the outcome. This case reinforces the principle that transparency and contestability are central to responsible ADM. |

Ongoing monitoring

Ongoing monitoring is key to the lifecycle of ADM systems and should be designed to ensure that the relevant ADM system remains lawful, fair, accurate and operating as intended. Some examples of measures which may be appropriate include:

- referral pathways – ADM systems should be designed such that outputs or cases that fall outside normal parameters are automatically referred to a human decision-maker for review;

- spot checks and audits – ADM systems should involve regular human review of a sample of automated decisions to detect errors, biases or unintended outcomes. These can be random spot checks or targeted reviews as well as independent expert audits;

- version control – where changes are made following monitoring, organisations should maintain detailed records of system versions, changes and the rationale for these updates so that these decisions can be traced and explained; and

- clear accountability – monitoring and updating of ADM systems should be assigned to specific roles or teams.

Conclusion

Organisations that embed transparency, robust data governance, rigorous testing and defined accountability into their ADM design and procurement will be better placed to meet evolving regulatory expectations. Practical priorities for organisations adopting ADM processes or systems should include strengthening monitoring and human review mechanisms, clarifying contractual accountability with suppliers and designing accessible processes for individuals to contest significant automated outcomes. Taking such actions will assist with reducing legal exposure and encourage the trust of customers and the community as ADM inevitably becomes more complex and deeply integrated into business operations.

Footnotes

1. Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Cth).

2. See Australian Government, 'Government Response: Privacy Act Review Report' (28 September 2023).

3. Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer, 'Australia releases new mandatory guardrails and voluntary standards on AI – what you need to know' (September 2024) [https://www.hsfkramer.com/insights/2024-09/australia-releases-new-mandatory-guardrails-and-voluntary-standards-on-ai].

4. Productivity Commission's 'Harnessing data and digital technology' interim report (August 2025) [https://assets.pc.gov.au/2025-09/data-digital-interim.pdf?VersionId=rbzZkLQzxhnPQz4O6MwZ.moIhJRyarOo]; see also the Government's recent review into whether Australian Consumer Laws were fit for purpose found that they were capable of protecting consumers in the context of AI goods and services, along with other laws: https://treasury.gov.au/review/ai-australian-consumer-law].

5. Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 'National AI Plan' [https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/national-ai-plan].

6. Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 'Guidance for AI Adoption' [https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/guidance-for-ai-adoption#read-the-guidance].

7. Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 'How we developed the guidance' [https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/guidance-for-ai-adoption/how-we-developed-guidance].

8. Work Health and Safety Amendment (Digital Work Systems) Bill 2025.

9. See Work Health and Safety Amendment (Digital Work Systems) Bill 2025 [https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/bills/Pages/bill-details.aspx?pk=18847], Schedule 1.

10. See 'NSW Government strengthens guardrails around digital safety in workplaces' (NSW Government) [https://www.nsw.gov.au/ministerial-releases/nsw-government-strengthens-guardrails-around-digital-safety-workplaces].

11. Ibid.

12. For example, ACCC v Trivago N.V. (2020) 142 ACSR 338; ACCC v Trivago N.V. (No 2) (2022) 159 ACSR 353; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Uber BV [2022] FCA 1466; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v iSelect Ltd [2020] FCA 1523.

13. See s 361 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

14. See, eg, Yava Bathaee, 'The Artificial Intelligence Black Box and the Failure of Intent and Causation' (2018) 31(2) Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, 891-893.

15. Sunam Jassar et al., 'The future of artificial intelligence in medicine: Medical-legal considerations for health leaders' (2022) 35(3) Healthcare Management Forum, 185, 187.

16. For further details, see Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme, Final Report (released 7 July 2023).

17. Mobley v Workday, Inc. 3:23-CV-00770.

18. OAIC's Privacy Act Review Issues Paper submission [ https://www.oaic.gov.au/engage-with-us/submissions/privacy-act-review-issues-paper-submission/part-5-notice-and-consent.], para 5.12, 5.15.

19. Commonwealth Ombudsman's 'Better Practice Guide: Automated Decision Making' [https://www.ombudsman.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/317437/Automated-Decision-Making-Better-Practice-Guide-March-2025.pdf], pg 44-45.

20. Attorney General Department's Consultation Paper

on the Use of automated decision-making by government [https://consultations.ag.gov.au/integrity/adm/user_uploads/consultation-paper-use-of-automated-decision-making-by-government.pdf#:~:text=The%20Robodebt%20Royal%20Commission%20recommended%20that

%20where%20ADM%20is%20implemented%2C%20business%20rules%20and%20algorithms%20should%20be%20made%20available%20to%20allow%20independent%20expert%20scrutiny.]

] and OAIC's submission to the Attorney General

Department's Consultation Paper on the Use of automated

decision-making by government [ https://www.oaic.gov.au/engage-with-us/submissions/agd-consultation-paper-use-of-automated-decision-making-by-government].

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.