It's Nothing Personal: Federal District Court Recognizes English Judgment Against Foreign Debtor Not Subject to Personal Jurisdiction in New York

Southern District of New York: Standing alone, lack of personal jurisdiction was not a viable defense to recognition of a foreign money judgment where the debtor's other defenses were "meritless on their face" or "wholly lacking in evidentiary support."

Cargill Financial Services International Inc. v. Barshchovskiy, 2025 WL 522108 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 18, 2025).

A two-step process governs the recognition and enforcement of foreign money judgments in New York. First, recognition of a foreign judgment under Article 53 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules ("CPLR") essentially converts the foreign judgment into a New York state or federal court judgment. Once recognized, the judgment may then be enforced against the debtor's assets in the jurisdiction in accordance with CPLR Article 52. These distinct steps have different jurisdictional requirements: while personal jurisdiction over the judgment debtor is not invariably required for recognition of a foreign money judgment, the debtor or third-party garnishee holding the debtor's assets may still challenge the court's jurisdiction to enforce the judgment. In that case, the creditor must show that the court has personal jurisdiction over the debtor or garnishee, or quasi in rem jurisdiction limited to the value of the debtor's assets in New York.

Cargill sought recognition of an English Commercial Court judgment confirming an LCIA arbitration award of approximately $124 million against Ukrainian businessman Taras Barshchovskiy. The judgment originated from an arbitration over Barshchovskiy's alleged failure to pay debts under 27 individual agreements. After the award was rendered, Barshchovskiy unsuccessfully challenged it in English court, claiming the tribunal was not impartial and had denied him a reasonable opportunity to present his case. The English court rejected these defenses and issued a judgment confirming the award's terms.

When Cargill brought an action in New York to recognize the English judgment under CPLR Article 53, Barshchovskiy argued that the court lacked personal jurisdiction over him. The court explained that personal jurisdiction is not required for recognition, either under Article 53 or by due process, unless the judgment debtor "place[s] in question" the judgment's entitlement to recognition with substantive defenses, such as fraud or denial of due process in the underlying proceeding. Otherwise, a personal jurisdiction requirement for recognition would create a "game of judgment enforcement whack-a-mole," allowing debtors to evade enforcement by moving assets before courts could act, depriving the court of jurisdiction, and undermining the purpose of giving creditors tools to locate assets.

The court found Barshchovskiy's defenses did not place the foreign judgment in question because they were either "meritless on their face" or "wholly lacking in evidentiary support." His objections to the foreign judgment targeted the underlying arbitration rather than the foreign judgment itself—a critical distinction since the English court judgment was the subject of the recognition proceedings, not the arbitration award. Moreover, even if the English court had not already rejected Barshchovskiy's purported defense based on fraud in the underlying arbitration, that allegation was "so general as to be meaningless." Without colorable defenses, the court held its role was "merely ministerial," requiring no personal jurisdiction.

The result likely would have been different had Cargill sought recognition of the LCIA award itself under the New York Convention and Chapter 2 of the Federal Arbitration Act. In award (as opposed to judgment) recognition proceedings, the enforcing court must deny recognition if the debtor demonstrates that it is not subject to the court's personal jurisdiction—regardless of whether the debtor challenges recognition on any other grounds. By seeking recognition of the English judgment confirming the LCIA award, Cargill was able to avoid that outcome.

Read the court's full decision here.

Careful Where You Click: New York's Highest Court Enforces "Clickwrap" Arbitration Agreement to Bar Consumer's Previously-Filed Lawsuit

New York Court of Appeals: "Clickwrap" arbitration agreement applied to ride-hailing passenger's personal injury claims in already-pending lawsuit against Uber.

Wu v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 2024 WL 4874383 (N.Y. Nov. 25, 2024).

Under New York's "objective standard," contract formation requires the parties to have (at least) "inquiry notice" of the agreement's terms, along with a "clear and objective manifestation" of their assent to be bound by them. Because the standard is objective, a party who accepts a written contract without reviewing it generally bears the risk that the agreement may contain unexpected provisions, unless the offeror's wrongful conduct prevents the offeree from understanding the terms.

Plaintiff Emily Wu was injured when, after being dropped off by an Uber driver in Brooklyn, she was struck by another vehicle. As a result, Wu filed a personal injury lawsuit against Uber. Two months later, while her lawsuit was pending, Uber updated its terms of service to require mandatory arbitration to resolve "any dispute, claim or controversy . . . whether the dispute, claim or controversy occurred or accrued before or after the date you agreed to the Terms" (emphasis added). The next time Wu opened her Uber app, she was presented with a pop-up screen announcing updated terms. Wu checked a box indicating she had "reviewed and agreed to the Terms of Use" and clicked "Confirm." When Uber moved to compel arbitration based on these updated terms, Wu objected, arguing that she never validly agreed to arbitrate her pending lawsuit.

In a 5-2 decision, the Court of Appeals sided with Uber, finding that a binding arbitration agreement had been formed through that so-called "clickwrap" process. Judge Cannataro, writing for the majority, concluded that Uber's pop-up screen put Wu on "inquiry notice" of the January 2021 terms, and that she objectively manifested her assent by checking the box and clicking "Confirm." While Wu argued the arbitration agreement was unenforceable because Uber's practices were deceptive and unconscionable, the clickwrap arbitration agreement provided "that the arbitrator would have 'exclusive authority' over any disputes relating to the applicability or enforceability of the arbitration agreement," including whether its terms were unconscionable. On that basis, the majority found, Wu was required to present her arguments "to a neutral arbitrator, not the courts."

In dissent, Judge Rivera, joined by Chief Judge Wilson, argued that no reasonable person would have understood that agreeing to the updated terms would "force them to arbitrate previously filed, currently pending claims." In the dissent's view, this amounted to a fatal formation defect, as a contract requires "a manifestation of mutual assent sufficiently definite to assure that the parties are truly in agreement with respect to all material terms."

Read the court's full decision here.

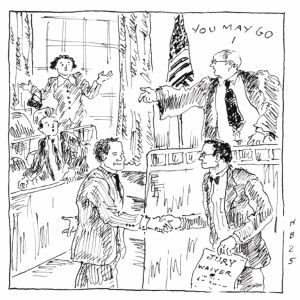

"Waiving" Goodbye to the Jury: Appellate Division Upholds Contractual Jury Waivers Despite Fraud Claims

First Department: A contractual jury waiver between sophisticated parties applies to fraudulent inducement claims unless the plaintiff challenges the validity of the entire agreement.

International Business Machines Corporation v. GlobalFoundries U.S. Inc., 235 A.D.3d 22 (1st Dep't 2024).

lthough contractual jury waivers between sophisticated parties are generally enforced in New York, they may become unenforceable in case of fraud. But not all fraud claims invalidate a jury waiver. The First Department recently clarified that a jury waiver provision may not apply where the plaintiff's "primary claim is [for] fraudulent inducement and the validity of the entire contract is clearly being challenged," but a broad jury waiver remains enforceable where the plaintiff seeks "to enforce the underlying contract by obtaining damages for fraudulent inducement." This case, the court explained, "f[ell] into the latter category."

IBM and GlobalFoundries entered into a series of agreements in 2014-2016 whereby IBM transferred its microelectronics business and $1.5 billion to GlobalFoundries in exchange for the latter's commitment to develop and supply 14nm and 10nm semiconductor chips. Each agreement contained broad jury waivers "to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law" and covering any proceeding, "whether in contract, tort, equity or otherwise," "directly or indirectly arising out of, under or in connection with" the agreements.

Shortly after closing the transaction, GlobalFoundries repudiated its obligation to develop the 10nm chips and proposed developing more advanced 7nm chips instead. Despite this development, the parties later amended their agreements on other terms but retained the broad jury waiver provisions. Eventually, GlobalFoundries abandoned development of both the 10nm and 7nm chips, though it continued to supply the 14nm chips specified in the agreements. After receiving the last of the 14nm chips, IBM sued GlobalFoundries for fraudulent inducement, breach of contract, and promissory estoppel. When IBM demanded a jury trial, GlobalFoundries moved to strike the demand based on the contractual jury waivers. The trial court granted the motion, and IBM appealed.

The First Department affirmed, finding IBM's "primary claim [wa]s not fraudulent inducement but rather breach of the agreements," meaning that IBM's fraud claim did not challenge the enforceability of the jury waivers. The court distinguished other fraud cases where jury waivers were invalidated on the ground that IBM made only a single allegation of fraud, unlike the multiple fraud allegations in the other cases that were the "central premise of the party's position." Moreover, IBM had continued to perform under the agreements after it became aware of GlobalFoundries' alleged fraudulent conduct, even amending the agreements in March 2016 after learning GlobalFoundries would not develop the promised chips, while retaining the jury waiver. According to the court, these facts showed IBM "merely s[ought] to enforce the underlying agreements by obtaining damages . . . and d[id] not challenge the validity" of the jury waiver.

Read the court's full decision here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.