- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- within International Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Healthcare, Property and Law Firm industries

Key Takeaways

- Effective Jan. 19, 2025, the USPTO implemented a new fee framework for IDS submissions, charging up to $800 for applications that list more than 200 references. The change is aimed at curbing over-disclosure and helping examiners focus on the most relevant prior art.

- Biotech and life sciences applications often generate large volumes of references, making it difficult and costly to selectively curate submissions without risking inequitable conduct claims.

- Practitioners should approach IDS strategy with care, especially when submitting large volumes of prior art. Recent decisions show that burying key references, even if disclosed, can still leave patents vulnerable if the record suggests the examiner didn't meaningfully consider them.

A series of procedural changes at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is influencing strategy for biotech and life sciences applicants. Over the past year, the agency introduced two new fees and launched a streamlined examination pilot, each with implications for how and when applications are filed. This update is the third in a three-part series discussing these changes and their implications for biotech and life sciences companies. Click here to read Part 1 and Part 2.

Here, we break down the USPTO's new tiered fee structure for Information Disclosure Statements (IDS) and what it means for applicants managing high volumes of prior art, strict Rule 1.56 obligations and evolving IPR risk.

USPTO's New IDS Fees Target Examination Burden

Effective Jan. 19, 2025, the USPTO introduced a new fee structure for submitting IDS, which applicants use to satisfy their duty of candor and good faith when filing and prosecuting patent applications.1

In announcing the new IDS fee framework, the USPTO noted that approximately 87% of applications contain 50 or fewer applicant-provided items of information and approximately 77% contain fewer than 25 items. Of the IDS submissions having greater than 50 items, about 5% of applications contain 51 to 100 items, about 4% of applications contain 101 to 200 items and about 4% of applications contain more than 200 items.

Despite providing examiners with approximately 80,000 additional hours each year to consider large IDS submissions, the USPTO maintains that it "is onerous for examiners and hinders the USPTO's statutory obligation to timely examine applications under 35 U.S.C. 154 to consider large numbers of clearly irrelevant, marginally relevant, or cumulative information," and that considering such large IDS filings is costly.

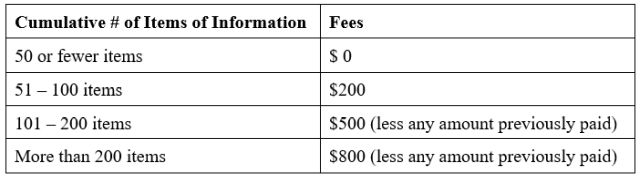

To address this, the USPTO created a three-tier fee structure for IDS filings:

Why Biotech IDS Strategy Remains a High-Stakes Calculation

The USPTO noted that the IDS size fee may encourage applicants to filter out clearly irrelevant, marginally relevant or cumulative information, which — in turn — will allow examiners "to focus on the more relevant information and perform a more efficient and effective examination" to the benefit of the patent system as a whole.

But for biotech and life sciences applications, the IDS size fee may have limited impact. These applications are frequently built from grant applications and draft manuscripts, where the number of relevant or potentially relevant references can escalate quickly.

As it is often cost prohibitive to evaluate each reference individually, patent practitioners are inclined to submit all or most of the references, as a finding of inequitable conduct in any ensuing litigation can be devastating. Specifically, if a court finds that a practitioner engaged in inequitable conduct — by, for example, failing to provide in an IDS one or more references that are deemed material to the patentability of a claim (thereby violating the Rule 1.56 duty of good faith and candor) — then all claims are rendered invalid or unenforceable. Submitting a comprehensive IDS submission not only ensures that the patent practitioner has fully discharged the obligations of Rule 1.56, but it can also shield a patent for the institution of an Inter Partes Review (IPR).

A Cautionary Example: The '202 Patent and a 1,000-Reference IDS

Consider the recent history of U.S. Patent No. 11,925,202 (the '202 patent). In denying a petition for IPR of the '202 patent, the PTAB indicated that the references asserted in the IPR petition had been previously presented in an IDS during examination of the application. But, this was no ordinary IDS. The submission included more than 1,000 references, including the four cited in the petition. And, although the examiner requested that the applicant identify any reference or portion thereof that warranted particular attention, the applicant did not comply. The examiner then processed the IDS by making of record all provided references.

In response, the petitioner requested director review of the decision, arguing that the PTAB misapplied both parts of the two-part Advanced Bionics, LLC framework for evaluating whether a discretionary denial under Section 325(d) is warranted.2

The first prong of Advanced Bionics framework is satisfied by showing that the asserted prior art was presented to examiner using an IDS. And although the petitioner failed to provide an analysis under the second prong of the analysis, the director's decision resolved any ambiguity by clarifying that "a petitioner must provide an analysis even when the asserted prior art is on an IDS, but the examiner did not apply the reference."

In other words, even when the asserted prior art was previously included in an IDS, the petitioner must still explain how the examiner erred in "overlooking the prior art" and must do so with a focus on several Beckton Dickison factors.3

In remanding the proceeding back to the PTAB,4 the acting director instructed the board to consider "whether discretionary denial is appropriate in view of the 1,000-reference IDS and the applicant's tacit refusal to identify references in response to the examiner's request." The director's order effectively acknowledged the potential for a patent examiner to overlook references that are submitted in a very large IDS submission.

On remand, the PTAB agreed that the petitioner had now demonstrated how the Office erred by not substantively considering the four references during the prosecution of the challenged claims. The PTAB also acknowledged that "the Office error may be attributed, at least in part, to the applicant's failure to respond to the examiner's request to identify the relevant references and portions of references among the extraordinarily large number of references cited on the IDS." Accordingly, the PTAB declined to exercise its discretion to deny institution under § 325(d). However, the PTAB then exercised its discretion to deny institution under 35 U.S.C. § 314(a) because the corresponding ITC investigation was at an advanced stage (e.g., discovery and claim construction are complete and an evidentiary hearing was held).

The Takeaway: A Large IDS Doesn't Insulate Against IPR Risk

While providing examiners with an IDS submission identifying quality prior art can shield patent from IPR, burying the best prior art in a voluminous IDS submission and ignoring examiners' requests for assistance can also be considered by the PTAB when exercising its discretion to institute an IPR petition. Practitioners should weigh the risks of over-disclosure just as carefully as under-disclosure and be prepared to justify their approach.

Footnotes

1. Under 37 C.F.R. § 1.56, "each individual associated with the filing and prosecution of a patent application has a duty of candor and good faith in dealing with the Office, which includes a duty to disclose to the Office all information known to that individual to be material to patentability as defined in this section." This Rule then defines information as material to patentability when it is not cumulative to information already of record and when (i) the information establishes, by itself or in combination with other information, a prima facie case of unpatentability of a claim; or (ii) the information refutes, or is inconsistent with, a position the applicant takes in either opposing an argument of unpatentability relied on by the Office, or asserting an argument of patentability.

2. See Advanced Bionics, LLC v. MED-EL Elektromedizinische Geräte GmbH, IPR2019-01469, Paper 6 (PTAB Feb. 13, 2020) (precedential).

3. Specifically, the relevant Beckton Dickinson factors include Factor (c) (i.e., the extent to which the asserted art was evaluated during examination, including whether the prior art was the basis for rejection; Factor (e) (i.e., whether Petitioner has point out sufficiency how the Examiner erred in its evaluation of the asserted prior art); and Factor (f) (i.e., the extent to which addition evidence and facts presented in the Petition warranted reconsideration of the prior art or arguments).

4. (Ecto World, LLC v. RAI Strategic Holdings, Inc. (§ A), IPR2024-01280, Paper 13 (May 19, 2025) (designated: May 19, 2025).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.