The question presented to the U.S. Supreme Court in the copyright infringement case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, was whether the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF)'s decision to license one of Warhol's Prince Series images—a set of silkscreen prints authored by Andy Warhol and derived from Lynn Goldsmith's photograph of the singer-songwriter, Prince—constituted "fair use." Justice Sotomayor, writing for the 7-2 majority, said it did not. Affirming the Second Circuit opinion, the majority held that the "purpose and character" of AWF's particular commercial use of Goldsmith's photograph did not favor a finding of fair use pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 107(1). Justice Gorsuch filed a concurring opinion, in which Justice Jackson joined. Justice Kagan filed a dissenting opinion, in which Chief Justice Roberts joined. Importantly, the majority expressly stated that it was not deciding whether Warhol's use of the image to create the Prince Series was, or was not, fair use. Or whether displaying the Prince Series (e.g., in a museum) would be fair use. Rather, the opinion takes great pains to confine its opinion to AWF's commercial conduct, i.e., the license fee it charged for the use of the image on a magazine cover.

Setting the Stage: Lynn Goldsmith Licenses Prince's Portrait to Vanity Fair

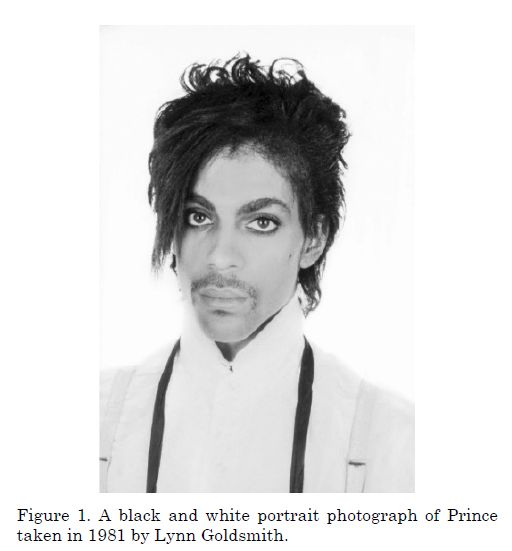

In 1981, Prince Rodgers Nelson was an "up and coming," "hot young musician." Prince booked a concert at the Palladium in New York City and rock-and-roll photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, convinced Newsweek magazine to hire her to shoot the gig. Goldsmith took additional photos of Prince at her New York studio. Newsweek ultimately ran one of the concert prints alongside its article, "The Naughty Prince of Rock," and Goldsmith kept the remaining photos. Goldsmith owns the copyright to all of the photographs.

One of the photographs is a black-and-white portrait of Prince that Goldsmith took in her studio, depicted below. In 1984, Goldsmith licensed the portrait to Vanity Fair to serve as an "artist reference for an illustration" to be published in Vanity Fair. The license agreement permitted only limited use of the portrait, specifically it could "appear one time full page and one time under one quarter page" and otherwise granted "[n]o other usage right." The license fee was $400.

Andy Warhol Takes the Stage: "Purple Fame" & the Prince Series

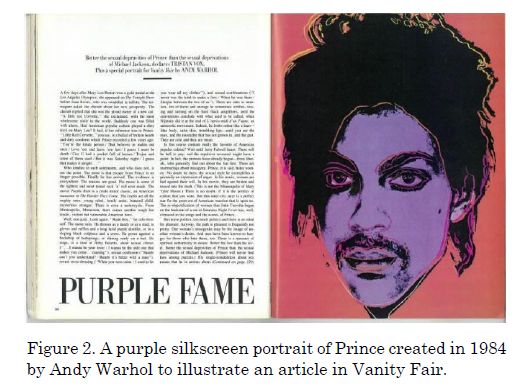

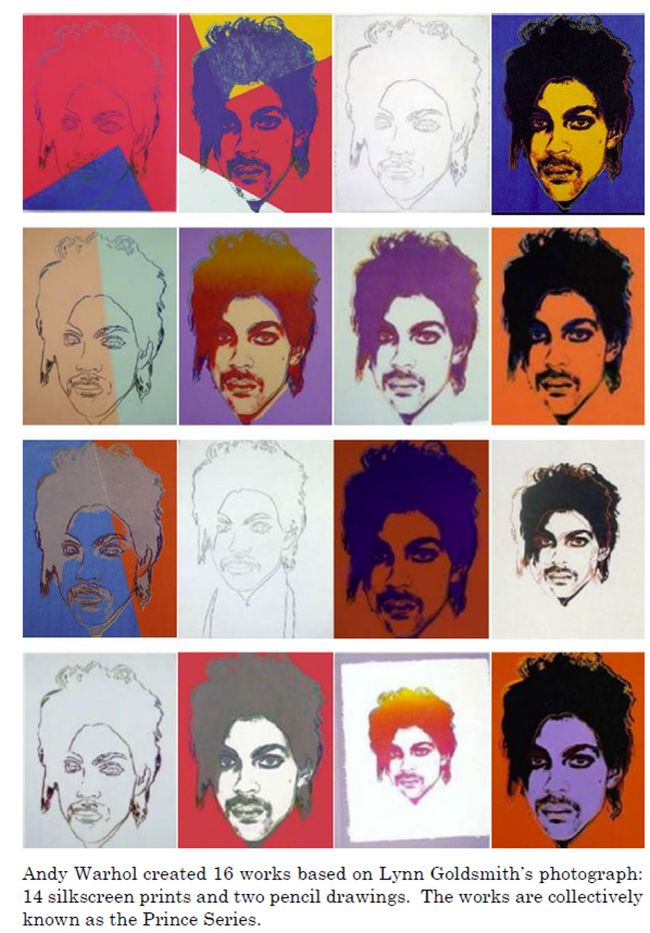

To create the illustration, Vanity Fair hired well-known American visual artist, Andy Warhol, known for, amongst other things, his silkscreen portraits of celebrities. Warhol created a purple silkscreen portrait of Prince to accompany Vanity Fair's article "Purple Fame," which highlighted the "sexual style" of Prince's music.

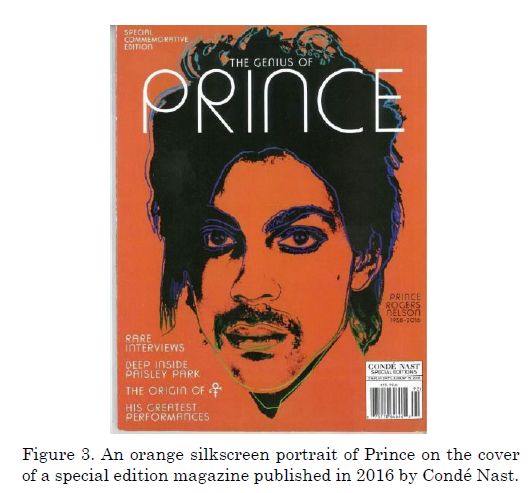

In addition to the purple silkscreen portrait, Warhol created 15 additional works based on Goldsmith's photograph, which included 13 silkscreen prints and 2 pencil drawings. The collection became known as the "Prince Series." Thirty-two years later, an orange silkscreen print from the Prince Series, referred to here as Orange Prince, would take the spotlight.

Copyright Infringement's Opening Act: Condé Nast Runs Orange Prince

The Artist Formerly Known as Prince died in 2016. Following his death, Vanity Fair's parent company, Condé Nast, published a special edition magazine titled "The Genius of Prince." On its cover, Condé Nast featured Orange Prince, which it had licensed from the AWF for $10,000. Condé Nast neither paid Goldsmith nor gave her source credit for its use of the Orange Prince image.

Goldsmith learned about the Prince Series for the first time in 2016 when she saw Condé Nast's tribute and Orange Prince. Goldsmith notified AWF of her allegation that AWF infringed her copyright by licensing the Orange Prince to Condé Nast. AWF responded by suing Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement or, in the alterative, fair use in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Procedural History Double Bill

Although Goldsmith established that, from the time Goldsmith had licensed the source image to Vanity Fair in 1984 to the time Prince died in 2016, she had licensed photos of Prince to several magazines, including People, Readers Digest, Guitar World, and Musician, for cover features, the district court granted summary judgment for AWF, finding the Prince Series were transformative, and the licensing of the works by AWF made fair use of Goldsmith's source image. Fair use, which is enumerated in 17 U.S.C. § 107, provides:

[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching . . . , scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

As to the first prong of the fair use analysis, the district court held the works were "transformative" because they "have a different character, give Goldsmith's photograph new expression, and employ new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from Goldsmith's." Specifically, the court wrote, the works "transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure," such that "each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a 'Warhol,' rather than as a photograph of Prince."

The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed and remanded. The court of appeals rejected the notion that "any secondary work that adds a new aesthetic or a new expression to its source material is necessarily transformative." Rather, "whether the secondary work's use of its source material is in service of a fundamentally different and new artistic purpose and character" is what matters. The Second Circuit held that in this case "the overarching purpose and function of the two works at issue . . . is identical, not merely in the broad sense that they are created as works of visual art, but also in the narrow but essential sense that they are portraits of the same person."

The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari to address the narrow question of "whether the court below correctly held that the first factor . . . weighs in Goldsmith's favor." Justice Sotomayor, writing an opinion for the majority, found that it did.

Headliner: Majority Finds First Fair Use Factor Weights in Goldsmith's Favor

The Court held that, for purposes of satisfying the first fair use factor, whether the use of a copyrighted work has a further purpose or different character "is a matter of degree," and that "the degree of difference must be balanced against the commercial nature of the use." Thus, "[i]f an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying."

At issue in this case was AWF's decision to license Warhol's Orange Prince to Condé Nast. The Court held that this use of Orange Prince was "substantially the same as that of Goldsmith's photograph" in that both are "used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince" even if not perfect substitutes. That use was also commercial in nature, having been licensed for $10,000.

AWF contended that the Prince Series works are "transformative," and that the first factor therefore weighs in its favor, because "the works convey a different meaning or message than the photograph." The district court accepted this argument, finding in the record evidence that the Prince Series "portray Prince as an iconic, larger-than-life figure" and "convey the dehumanizing nature of celebrity."

But that reasoning was insufficient for the majority. Instead, the Court held that "Campbell [v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U. S. 569 (1994)] cannot be read to mean that § 107(1) weighs in favor of any use that adds some new expression, meaning or message. Otherwise, 'transformative use' would swallow the copyright owner's exclusive right to prepare derivative works." Here, "the degree of difference [in the expressions] is not enough for the first factor to favor AWF, given the specific context of the use." To permit otherwise, the majority cautions, would permit a copyist to "make modest alterations to the original, sell it to an outlet to accompany a story about the subject, and claim transformative use."

The majority also noted that the asserted expressive commentary "has no critical bearing on Goldsmith's photograph" and thus its "claim to fairness in borrowing from [Goldsmith]'s work 'diminishes accordingly.'" This can be contrasted with Campbell where use of the underlying source material was necessary to the parody. Further, the Court implied that satire, which by definition does not target an original work, and the commentary "can stand on its own two feet" may be viewed under an even stricter standard, requiring "justification for the very act of borrowing."

Thus, the Court found that "[e]ven though Orange Prince adds new expression to Goldsmith's photograph, . . . in the context of the challenged use, the first fair use factor still favors Goldsmith."

Encore: Justices Gorsuch's and Jackson's Concurrence

The concurring opinion directly addresses the parties' disagreement about which "purpose" and "character" to apply to the first factor. AWF focused on the purpose of the creator, i.e., Warhol, when creating the Orange Prince. Goldsmith focused on the purpose and character of the challenged use, i.e., the license granted to Condé Nast for use as a cover image. The concurring Justices found no statute "call[ing] on judges to speculate about the purpose an artist may have in mind when working on a particular project."

Instead, Justices Gorsuch and Jackson found that the statute "asks [a court] to assess whether the purpose and character of [a] use is different from (and thus complements) or is the same as (and thus substitutes for) a copyrighted work." They argue that this interpretation is supported by (1) the statutory preamble, which lists various uses; (2) the derivative works definition, which necessarily implies a copyright owners ownership over certain transformations of the underlying work; and (3) the case law supporting the importance of the fourth fair use factor and warning against treating each factor in isolation.

The Dissent: Justice Kagan and Chief Justice Roberts Warn That the Majority Opinion Will "Stifle Creativity of Every Sort"

Justice Kagan and Chief Justice Roberts dissent from the majority's opinion that "Warhol's licensing of the silkscreen to a magazine precludes fair use." To them, "the majority's lack of appreciation for the way [Warhol's] works differ in both aesthetics and message from the original templates" is one that "hampers creative progress and undermines creative freedom."

The first fair use factor "is distinctive: It is the only one that focuses on what the copier's use of the original work accomplishes." Citing Campbell, the dissent points out that "[t]he critical factor 1 inquiry, we held, is whether a new work alters the first with 'new expression, meaning, or message.'" The dissenters further argue that in Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 U. S. ___ (2021), the Court found that "transformative uses 'stimulate creativity' and thus 'fulfill[] the objectives of copyright law.'"

Justice Kagan further criticizes the majority for not giving enough credit to the way Warhol "'add[ed] something new, with a further purpose or different character'—all the ways he 'alter[ed] the [original work's] expression, meaning, [and] message'" and instead created a "commercialism-trumps-creativity analysis" that and is better suited for factor 4. The "one way out," noted by the dissent, would be "[i]f Warhol had used Goldsmith's photo to comment on or critique Goldsmith's photo" But because he instead "commented on society—the dehumanizing culture of celebrity" Orange Prince did not satisfy the first factor. This holding, the dissent stated, "is not faithful to our precedent."

Turning to text, Justice Kagan objects to the majority's allegedly "reductionist view" of the "character" part of the first factor, claiming that "everyone (save the majority) knows—about the differences in expression and meaning between Goldsmith's photo and Warhol's silkscreen." She also condemns the majority's narrowing of the "purpose" reference to exclude Warhol's artistic purposes and to focus only on the licensing activity.

In sum, the dissent worries that the majority's opinion "impedes non-copyright holders' artistic pursuits, by preventing them from making even the most novel uses of existing materials."

The Audience Reaction: Thoughts and Takeaways on Potential Reverberations

This eagerly anticipated opinion certainly did not disappoint in terms of the unusual alignment of Justices and the high-spirited rhetoric. Warhol probably would have loved it. It is expected to have an immediate impact on pending cases where fair use is at issue including, for example, the various embedding disputes, appropriation art, and generative AI litigations.

The Court was narrowly focused on whether fair use applied to AWF's licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast. It did not opine as to whether other uses of the Prince Series, including whether Warhol's creation of the Orange Prince in the first instance, constituted fair use. The Court provides clues of uses that it would likely consider to be fair (e.g., uses listed in the fair use preamble, parody) but satire could be a harder lift. As to the balance of factors, there appears to be room for parties to argue as to how a specific use is determined, whether the purpose and character of the infringing use is sufficiently similar to use of the copyrighted work, and what types of justifications are persuasive enough to overcome a more-commercial-than-transformative use.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.