With the growth of the Islamic finance industry, there have been significant developments in the structures used to effect Shari'a-compliant financings as well as in the techniques used to implement these structures, including balance sheet and off balance sheet financings. Islamic syndicated financing is one of these techniques.

This Note:

- Examines Islamic syndicated financing and its similarities to and differences from conventional syndicated financing.

- Explains the techniques used to structure Islamic syndicated loans.

- Analyzes the issues to consider when structuring an Islamic syndicated loan transaction and developing a strategy for a successful syndication.

- Examines the future of Islamic syndicated financing.

Similarities to and Differences from Conventional Financings

Generally, Islamic syndication has the same conceptual foundation and takes into account the same commercial considerations as conventional syndication, but there are material differences between the two transactions that must be considered.

Similarities to Conventional Syndicated Financings

To better understand Islamic syndicated financing, it is important to examine what this concept means in its more entrenched conventional equivalent. In a conventional syndicated financing, the loans to the borrower are shared among two or more banks or other financial institutions (collectively, the lenders). The syndication may be structured either as a:

- Fully underwritten deal. In this case, the lead bank (also referred to as the arranger) commits to fund 100 percent of the loan whether or not it is able syndicate part of the loan to other lenders.

- Partially underwritten deal. In this type of deal, the arranger commits to use its best efforts or commercially reasonable efforts to arrange a syndicate of lenders that will make the loan but has no obligation to fund any part of the loan itself. If the loan is fully syndicated, the arranger may fund a small portion of the loan. If the loan is not fully syndicated, its terms are either renegotiated or the loan does not close. Arrangers often prefer to use the "commercially reasonable efforts" standard because it is believed to be a slightly more lenient standard than "best efforts" (which, while not a clear standard, is believed by practitioners to require extraordinary measures).

Similar to conventional transactions, an Islamic loan transaction may be syndicated before or simultaneously with financial close or after financial close (and earmarked for distribution in the primary market or the secondary market). However, unlike conventional financings, there are timing issues that must be considered.

Islamic syndicated financings are derived from the same concepts and must take into account the same commercial considerations and provide the same protections as conventional syndicated financings from the perspective of both the borrower and the participating lenders. These include:

- Allowing lenders to mitigate their exposure by sharing the borrower's credit risk

- Allowing lenders to participate in more transactions than they may have otherwise and thereby diversify their loan portfolios because they are only taking a portion of each loan transaction.

- Enabling the borrower to raise more capital than it may have otherwise if it had only one lender.

Differences with Conventional Syndicated Financings

While there are a few differences between Islamic syndicated loans and conventional syndicated loans, the principal difference is the philosophical underpinning of these transactions. In conventional loan syndications, commercial and legal considerations are generally the only issues that determine the terms and forms of these transactions and the rights of the parties. By contrast, Islamic loan syndications:

- Must comply with Shari'a principles including the prohibitions against Riba, Gharar, and Maisir.

- Cannot invest in products and services that are Haram. For example, the borrower cannot be involved in the manufacture, production or sale of tobacco products, pork or alcohol or involved in providing gambling or pornographic activities or services.

- Require the approval of Shari'a scholars or the Shari'a committees of the lenders.

However, Islamic finance institutions are as interested in protecting their investments and making a return as their conventional counterparts. So while an Islamic syndicated transaction must abide by the conditions set forth above, it must also make financial sense. As a result, any structure that is ultimately adopted must give the lenders the same rights, benefits, and protections as they would have in a conventional syndicated financing. This is especially important in transactions involving conventional lenders or the Islamic windows of conventional financial institutions who may not be as aware or sensitive to Shari'a principles.

Structuring the Relationship Between the Arranger and the Other Lenders

In an Islamic syndication, the relationship between the arranger and the syndicate is structured in the same way as conventional financings. Typically the arranger, known in an Islamic syndicated financing as the investment agent or Wakeel, enters into an investment agency agreement with the other lenders under which it is given the authority to act as the lenders' agent. In this capacity, the investment agent:

- Negotiates with the borrower and coordinates the drafting and preparation of the loan documents.

- Monitors the transaction and the borrower's compliance with its obligations under the loan documents.

- Manages the relationship with the borrower, including receiving notices and responding to queries.

- Keeps the other syndicate banks apprised of developments at the borrower.

In exchange for performing these services, the Wakeel, like a facility agent in a conventional syndicated financing, would expect to receive administrative or other appropriate fees.

Structuring the Loans to the Borrower

Generally, any Shari'a-compliant structure may be used to document the loan. The structure used depends on:

- The purpose of the financing.

- The assets that will be used to repay the loans.

- The nature of the borrower's business.

- The amount of flexibility the parties require.

- The lenders' view of the Shari'a-compliant nature of the transaction.

The structures most commonly used to effect to an Islamic syndicated financing are:

- Murabaha.

- Commodity or reverse Murabaha (commonly referred to as Tawarruq).

- Mudaraba.

- Musharaka.

- Ijara.

- Istisna'a.

Murabaha

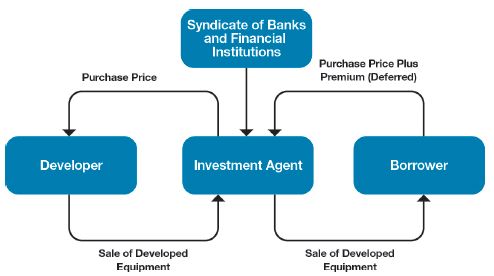

Commonly referred to as "cost-plus financing," Murabaha is frequently used in trade financing arrangements and to finance equipment. In this structure, the investment agent (as agent of the lenders) and the borrower typically enter into a Murabaha agreement under which the borrower agrees to buy an asset the investment agent, using funds received from the lenders, buys from a third-party supplier. The investment agent then sells the asset to the borrower at an agreed marked-up price. The borrower pays the marked-up sale price on a deferred basis in installments or as a bullet repayment. Typically the mark-up charged is based on a benchmark, such as LIBOR plus a margin. The economic effect of this structure is similar to an interest calculation under a conventional loan facility.

In a Murabaha-syndicated transaction, the investment agent holds title to the asset until it is sold to the borrower. Shari'a principles require that a seller owns the asset at the time it is offering to sell it. As a result, the investment agent (and, by extension, the lenders) bear the risk of loss, however briefly. Because the lenders bear this risk, the difference between the price the investment agent pays the third-party supplier and the marked-up price the borrower pays to purchase the asset from the investment agent is treated as a profit derived from a sale of the asset and not as interest on a disguised loan which is prohibited under Shari'a. Amounts paid by the borrower toward the purchase price of the asset are used to pay:

- The investment agent its agreed on fee.

- The syndicate banks (including the investment agent, if applicable) their pro rata share of the amounts they advanced.

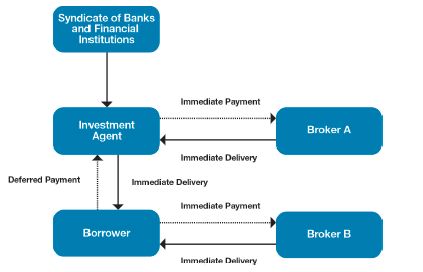

The following sets out a diagram of a typical Murabaha syndication transaction:

This structure, often referred to as a "true" Murabaha is used when the purpose of the transaction is for the borrower to acquire a particular asset. If the purpose of the transaction is instead for the borrower to obtain access to capital, the commodity Murabaha or Tawarruq structure is typically used.

Commodity Murabaha or Tawarruq

A variant on the Murabaha structure, a Tawarruq transaction involves many of the same steps. The investment agent and the borrower execute an agreement in which the borrower promises to buy an asset that the investment agent will then buy from a thirdparty supplier. However, in a Tawarruq:

- The investment agent purchases a freely tradeable asset in the spot market using the funds received from the lenders.

- The investment agent then immediately sells that asset at the agreed marked-up price to the borrower for immediate delivery. However, the borrower's obligation to pay the purchase price is deferred (to be paid in installments or as a bullet repayment at a later date).

- The borrower then immediately sells the asset in the spot market to a third party for immediate payment and delivery. The end result of these transactions is that the borrower receives cash which it can use to meet its working capital or other needs. A diagram of a typical Tawarruq-syndicated loan transaction is set forth below:

The commodity Murabaha may be used for a term loan or a revolver. In the case of the latter, the investment agent, on or before the drawdown dates, purchases additional assets on the spot market for resale to the borrower in the amount to be drawn down.

The Tawarruq structure is the most commonly used Islamic syndication structure. However, it has been criticized by the International Council of Fiqh Academy as a deception because the simultaneous transactions are a disguised interest-based financing which is prohibited under Shari'a. As a result, many Islamic financing institutions will not participate in a Tawarruq syndication and some Islamic scholars will not issue the Fatwa approving these transactions which is required to close Islamic finance transactions.

The sales by the investment agent and the borrower are done on a spot basis and occur virtually simultaneously. As a result, fluctuations are unlikely in the price of the asset between the time the investment agent buys it on the spot market and sells it to the borrower for the agreed price. While unlikely, this risk does exist and it is not assumed by the lenders. Lenders do not want to be in a position of having to sell the asset for a lower price than it acquired the asset. Therefore, the investment agent, on behalf of the lenders, typically requires the borrower to enter into a Murabaha agreement to indemnify the lenders in case there is a change in the value of the commodities.

In addition to the potential liability issues that must be dealt with, Murabaha participants must also consider the tax implications of the purchase and sales. For a discussion of the tax implications of these transactions in the U.S.

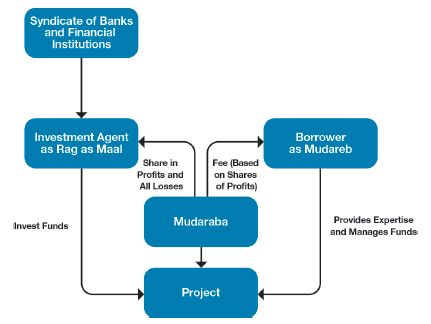

Mudaraba

A Mudaraba constitutes a special kind of partnership where one partner contributes money which is then invested by the other partner in a commercial enterprise. In a Mudaraba-based Islamic loan syndication, the borrower and the lenders (through the investment agent) form a partnership in which the lenders provide the money and the borrower provides the investment expertise. In a Mudaraba, the investment agent (the Rab al Maal), and the borrower (the Mudareb) share in any profits earned from the investment according to pre-agreed percentages.

These percentages are calculated to give the lenders an amount that is the functional equivalent of the periodic interest and principal payments that the borrower would make if the transaction was structured as a conventional financing. After receipt of these amounts from the borrower, the investment agent pays the lenders their pro rata share of these payments as provided in the Mudaraba agreement. Any losses from the investment are solely for the account of the investment agent (and ultimately, the lenders).

In exchange for investing the funds, the borrower receives a management fee. Because this is a financing arrangement, this fee is usually nominal. However, loan documents often require that this fee (together with any share of the profits to which the borrower may be entitled) be deposited into a segregated account and used to pay the lenders in case of a shortfall in the amounts required to repay the loans or following an event of default.

For a structure of a typical Mudaraba-syndicated transaction, see

A Mudaraba Can Be Either:

- A restricted Mudaraba (al-Mudaraba al-Muqayyadah). The investment agent or Rab Al Maal may specify a particular business for the Mudaraba, in which case the Mudareb must only invest in that business.

- An unrestricted Mudaraba (al-Mudaraba al-Mutlaqah). The Mudareb has discretion to invest the money advanced by the Rab al Maal in any Shari'a-compliant business it deems fit.

Because Shari'a requires that the Mudaraba participants share in the investment, this structure has fallen out of favor and lenders generally prefer non-partnership structures like the Tawarruq and Ijara.

Wakala

A common and preferred alternative structure to the Mudaraba structure is the Wakala, an Islamic agency arrangement. In a Wakala-based Islamic loan syndication, the investment agent appoints the borrower as its agent to manage the funds it receives from the lenders. In exchange, the borrower receives a pre-agreed fixed fee or a fee calculated as a percentage of the net asset value of the investment. Similar to the Mudaraba structure, these fees are often used repay shortfalls in amounts payable to the lenders. The profits earned from investing the loan proceeds in Shari'a compliant investments are paid periodically to the investment agent who uses these earnings to make payments (much like periodic interest and principal payments) to the lenders. Unlike the Mudaraba structure, the Wakeel does not have any discretion and must invest the funds for the specific purpose the investment agent has identified.

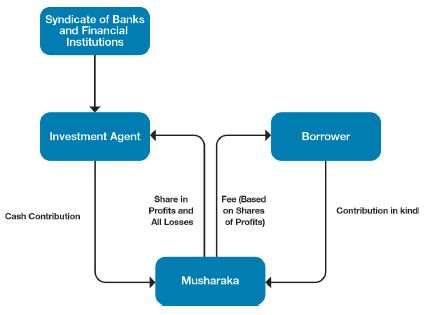

Musharaka

Under a simple Musharaka arrangement, a lender forms a joint venture with the borrower. The lender provides the financing to fund the venture and the borrower makes a contribution in kind. The Musharaka partners share the profit in agreed proportions but losses are shared in proportion to their initial investment. This arrangement is similar to an unincorporated joint venture. However, depending on the jurisdiction in which the Musharaka is formed, the Musharaka can take the form of a legal entity.

If the Musharaka structure is used to structure the Islamic syndicated financing, the lenders, through the investment agent, provide financing to the borrower for a project. The borrower makes contributions in kind (in the form of expertise, property or services) and acts as the manager of the Musharaka. It is responsible for investing the Musharaka assets to earn a return for the Musharaka partners.

Typically the profit sharing arrangements are structured in a way that ensures the lenders receive their agreed yield. The borrower may charge a management or investment fee, which may be the difference between the yield the lenders should receive as their share of the joint venture's profit and the amount the venture actually earns. This ensures that the lenders do not earn more than they would as earned interest or principal repayment. For a diagram of a typical Musharaka structure, see:

A Musharaka arrangement can take one of two forms:

- Muskaraka-Aqd.In this form, the lenders and the borrower agree to combine their efforts and resources towards a common objective. The borrower usually contributes a tangible asset and the lenders contribute cash through their investment agent.

- Musharaka-al-Melk. In this form, the lenders and the borrower act as co-owners of a specific asset or assets. The revenue is generated by leasing that co-owned asset to a third party or, as has become more common, by the lenders (acting through the Wakeel) leasing out their shares in that co-owned asset to the borrower.

A variation of the Musharaka arrangement is the diminishing Musharaka. Under this arrangement, the lenders (acting through the Wakeel) and the borrower participate in the joint ownership of a tangible asset or in a joint commercial enterprise. The shares owned by the investment agent and the borrower are divided into units and the borrower purchases the Wakeel's share on a periodic basis. This decreases the Wakeel's ownership share of the asset or joint commercial enterprise. The agreed proportions of the profits are used by the borrower to satisfy the commercially agreed payment profile, with the Musharaka coming to an end, at the term of the financing when all these payments have been made.

Similar to the Mudaraba structure, the Musharaka has fallen out of favor as a structure for Islamic syndications.

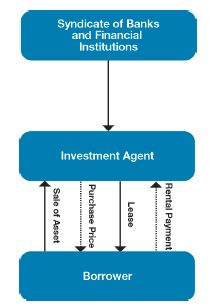

Ijara

The literal translation of Ijara is "to give something on rent" is basically a sale and lease back. Ijara in the context of a Shari'a compliant transaction means to transfer the usufruct of a particular property to another person in exchange for a rent claimed from that person or, more literally, a lease. The rules related to Islamic leasing are similar to the rules of sale as the asset is transferred to another person for valuable consideration. The only difference is that where the title to the asset passes on a sale, under an ijara title to the asset remains with the lessor.

Ijara is commonly referred to as a hybrid between an operating lease and a capital lease. It offers both the certainty of regular payments throughout the life of the financing as well the flexibility to tailor payment installments in a manner that allows the lenders to achieve a profit margin structure comparable to that in a conventional financing. While the traditional Ijara involves the lease of an existing physical asset, to enable the lenders to receive compensation during the period of construction, certain Shari'a scholars have permitted the use of the forward lease arrangement (known as Ijara Mawsufah fi al Fhima or Ijara fil Thimma). This is usually combined with an Istisna'a contract (see Istisna'a).

In an Islamic syndicated financing, the Wakeel uses the funds advanced by the lenders to purchase a Shari'a-compliant asset from the borrower which it then leases back to the borrower. The borrower pays rental payments (which may be tied to a benchmark (such as LIBOR) and coincide with the commercially agreed payment profile). At the end of the term of the financing, when all the payments have been made, the borrower has the right to buy back the asset.

For a diagram of an Ijara-based Islamic syndicated transaction, see:

The Ijara structure is the most accepted among Shari'a scholars and provides the most flexibility for purposes of developing a syndication strategy (see Method of Syndication). However, it does propose some issues, including:

- The borrower must have assets of sufficient value to sell to the investment agent to support the amount it wants to borrow.

- In the case of a revolving loan transaction, these assets (and in the required amount) must be sold on the drawdown dates.

- The assets must not be subject to any restrictions (for example, lien or other covenant restrictions) that preclude their sale to the investment agent.

These issues may make it difficult for borrowers with small asset bases or other debt obligations to do an Ijara-based loan.

Istisna'a

Istisna'a involves the investment agent requesting a manufacturer to manufacture a specific asset for the borrower in exchange for a fee. The Wakeel uses the funds provided by the lenders to pay the manufacturer. To be Shari'a-compliant, the arrangement must meet these conditions:

- The manufacturer must use its own materials to produce the asset.

- The price and specifications of the asset to be manufactured must be settled at the outset.

The investment agent then charges the borrower the price it pays the manufacturer, plus a commercially agreed rate of profit. Until the asset is delivered, the borrower is not obligated to purchase it. (However, to mitigate the lenders' risk, the borrower enters into a wa'ad with the Wakeel under which it promises to buy the asset). Therefore, although the Wakeel does not manufacture the asset itself, it takes the manufacturing risk of the asset.

For a diagram of a typical Istisna'a syndicated loan transaction, see:

An Istisna'a has, to date, been used in several different Shari'acompliant financing structures, most commonly for project financings. The Istisna'a structure is commonly used in conjunction with the Ijara structure. In this case, the borrower leases the asset once it is delivered to the lenders and uses the rental payments to pay the purchase price owed to the Wakeel. While the bank uses the Istisna'a method to advance funds to the borrower, the Ijara provides a repayment method for the borrower. The Wakeel, in turn, uses these funds to repay the other members of the syndicate.

This structure is often used for project financings or construction loans.

Issues for Developing a Successful Syndication Strategy

While Islamic syndicated financing is derived from the same fundamental notions and shares some of the same commercial considerations as a conventional syndicated financing, it does present some unique issues. These issues include:

- The absence of standard documentation.

- The Shari'a approval process.

- The methods of syndication.

Absence of Standard Documentation

The Islamic finance industry does not have a universally agreed form of documentation to match its conventional counterparts (which tend to use the documents prescribed by a loan market body, such as the Loan Market Association (LMA) in the UK and the Loan Syndication Transactions Association (LSTA) in the U.S.). As a result, the documents used in a Shari'a-compliant structure must be vetted by the lenders (with the assistance of their in-house legal team or external legal advisors) to ensure they understand their rights and obligations under the documents. This may be a cumbersome and time consuming process. However, these documents are typically based on LSTA and LMA forms which enable conventional lenders to participate in an Islamic syndication by giving them an established frame of reference for understanding their rights.

Shari'a Approval Process

The loan and syndication documents must also be approved by the Shari'a scholars or boards of the lenders. This may inhibit the syndication process because the arranger may not be able to sell down its underwriting commitment to a new bank or financial institution unless the financing or the structure is deemed compatible with Shari'a, as interpreted by the Shari'a scholars or boards of that new bank or financial institution. As noted above, certain transaction structures have been criticized as disguised loan transactions and some Islamic financial institutions will not participate in them (see Commodity Murabaha or Tawarruq).

These syndication-specific issues are in addition to the other issues that the Shari'a approval process may present such as:

- The insufficient number of Islamic scholars who are available to assess the Shari'a compliance of Islamic finance transactions.

- The over-representation of certain scholars on the boards of certain companies.

Method of Syndication

The arranger, the lenders and their respective counsel must also consider when and how the loan should be syndicated.

Assignment or Novation of the Loans

Depending on the structure of the transaction, Shari'a scholars or the Shari'a committees of the investment agent may not permit it to novate or assign its financing commitment. Shari'a prohibits trading in debt. The sale by the arranger of an interest in the loan, which is the essence of the syndication process, is not permissible. As a result, any novation or assignment must be of an asset. This is not an issue for asset-backed structures such as Ijara or Istisna'a. In these structures, the Wakeel is selling its interest in the underlying asset (the asset under lease in the case of an Ijara transaction or the asset being manufactured in the case of an Istisna'a).

However, this is an issue in structures that are not backed by an asset but that rely on a payment stream such as the Murabaha or the Tawarruq. In these structures, once the investment agent has sold the asset to the borrower, its only interest is the right to receive the purchase price of that asset.

Modification of the Loan Terms

Many conventional syndications, especially in the U.S., include flex language that allow the arranger to change the terms of the loan to give it the flexibility it may need to attract investors. Some of these transactions also include reverse flex language that gives the investment agent the right to modify the terms of the financing to make it more favorable to the borrower in case the loan is oversubscribed to give the borrower the benefit of an attractive deal. Flex language can also be included in Islamic syndicated financing, but depending on the change the agent wants to make, the investment agent may need to obtain the approval of its Shari'a committee. In addition, the agent must consider whether it can sell down the loan at a premium or discount. Generally, Shari'a scholars and boards only permit a sell down if it is done at par or if there is a tangible asset that backs the commitment being syndicated. This is intended to mitigate the argument that the lead bank is trading in debt which is generally not permissible under Shari'a principles. This, however, may cause a problem for the investment agent if the transaction is fully underwritten because it would be forced to fund the entire commitment if it cannot sell the loans at a discount to attract investors.

Participation of the Loan

Many conventional loan syndications give the lenders the right to participate the loans. Although superficially an Islamic syndication has components that are similar to a participation, it is a very different structure. If the lenders are considering a participation (or sub-participation, in the case of the UK), they must consider the following issues:

- Will it be permitted by their Shari'a committees? Because of the prohibition against trading in debt, a lender who wishes to participate a portion of its loan must do so at par unless the transaction is using an asset-backed structure. If an assetbacked structure is being used, the lender can sell any portion of its interest in the underlying asset at any price it chooses.

- If permitted, can it be effected through a funded or unfunded arrangement? In a funded arrangement, the participant gives the existing lender a deposit up front (which is a portion of the principal amount of the loan), to be repaid from the proceeds of the loan. By contrast, in an unfunded participation, the participant agrees to give the existing lender a portion of the loan under certain circumstances (for example, if the borrower defaults).

Timing of Syndication

Unlike conventional financings, most Shari'a-compliant structures do not allow for a stub period in connection with a syndication post financial close. This means that any new banks that are acquiring an interest in the loans post-closing must do so at an interval that coincides with the commercially agreed payment date. If the acquisition does not match a payment date or a commodity trading date, it may be viewed as trading in debt.

Presence of a Conventional Tranche

Many Islamic syndicated financings have a conventional tranche. The syndication strategy and documents may need to accommodate the syndication of the conventional tranche and the Islamic tranche. The conventional tranche must factor in the issues discussed above.

The Future of Islamic Syndication

Shari'a-compliant methods of financing have become prevalent among industry participants in the capital markets because of the current economic climate, and in particular, the refinancing risk to which many borrowers are now subject. However, although Islamic syndicated financing has increased considerably in the last 20 years, it has also suffered from the economic recession.

While there was some recovery in 2010 and 2011, Islamic syndicated financing in the first half of 2012 has been losing some of the strides it has made. This is due in part to the crisis in the Eurozone. According to Islamic Finance News (IFN), European banks, which were the major participants in Islamic syndicated financings, have withdrawn from the market to preserve their own liquidity and better manage their balance sheets. According to IFN, Islamic syndicated financings volumes in the Middle East and North Africa region was down 40 percent from the same period in 2011 at US$1.97 billion, which is the lowest volume since 2004.

When the global markets recover, Islamic syndicated financing volumes may increase. But to be a viable alternative to conventional syndicated financings on a grander scale it must provide the same protections as conventional syndicated financings. While great strides have been made, Islamic syndications lag way behind conventional syndications because of:

- The absence of uniform international Shari'a principles that can assure borrowers and investors that their transactions and structures are Shari'a-compliant, will be upheld and can give them the same confidence and protections they have in conventional syndicated financings.

- A developing secondary market for Shari'a-compliant financings which has, for the time being, led to investors holding their primary commitment.

The same perseverance and intellectual rigor which the Islamic finance industry has applied to its capital market and derivatives platforms must be replicated in developing the framework and scope of offerings regarding Islamic syndicated financings. This should not be difficult because compared to other Islamic finance products, such as Sukuk, an Islamic syndicated financing is relatively easy to implement. Despite the requirements that must be met to satisfy Shari'a, the concepts of Islamic syndicated financing are generally familiar to conventional lenders and use documents (albeit on a revised basis) that are well tested and understood.

This is particularly important because syndication remains an important tool that banks and other financial institutions use to manage their own balance sheets and financial condition, which has become even more important in the current economic and regulatory climate.

This article previously appeared in Practical Law Company, June 2012.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.