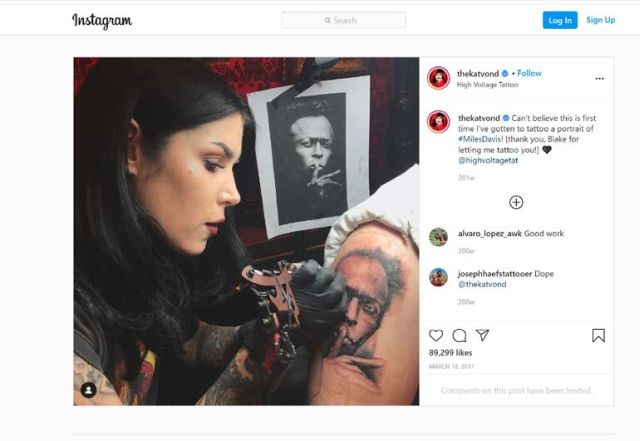

Katherine von Drachenberg using the Miles Davis reference. Screenshot from Complaint.

Famous tattoo artist Katherine von Drachenberg—better known by her celebrity moniker "Kat von D"—tattooed a picture of the legendary jazz musician Miles Davis on her friend, Blake Farmer. Kat von D used a photographic portrait of Miles Davis taken by photographer Jeffrey Sedlik. Sedlik owns a registered copyright for the Davis portrait.

The question presented to the jury in Sedlik v. von Drachenberg, et al. was whether Kat von D infringed Sedlik's copyright when she used the Davis portrait without Sedlik's permission. In January 2024, after only a couple of hours of deliberation, a jury unanimously ruled that Kat von D did not infringe because her tattoo art was not substantially similar to Sedlik's Davis portrait. Despite both parties making much ado about Kat von D's fair use affirmative defense, the jury did not reach that issue, leaving those questions unresolved. That said, the jury did return a verdict that Kat von D's social media posts including images of her tracing the Davis portrait and tattooing Farmer constituted fair use.

The Parties

Jeffery Sedlik is a prolific photographer and advocate for intellectual property rights associated with visual artworks. He runs a nonprofit called the PLUS Coalition, which promotes the licensing of visual works, and has served as an expert on copyright law's applicability to photography in numerous litigations and before Congress.

In 1989, Sedlik shot the iconic portrait of Miles Davis raising his finger to his mouth, which encouraged his listeners to quiet down and listen to the music. The portrait achieved some notoriety, as it was named one of Life Magazine's "Pictures of the Year" and featured on the cover of JAZZIZ Magazine.

A reproduction of Jeffery Sedlik's iconic Miles Davis portrait. Screenshot from Complaint.

Kat von D is a celebrity tattoo artist known for her lead role in the TLC reality television series LA Ink. In LA Ink, Kat von D is shown working on dozens of celebrities' tattoos.

In 2017, Kat von D gifted her friend, Blake Farmer, a tattoo inspired by the Miles Davis portrait. Farmer loves jazz, and Miles Davis is Farmer's favorite trumpet player.

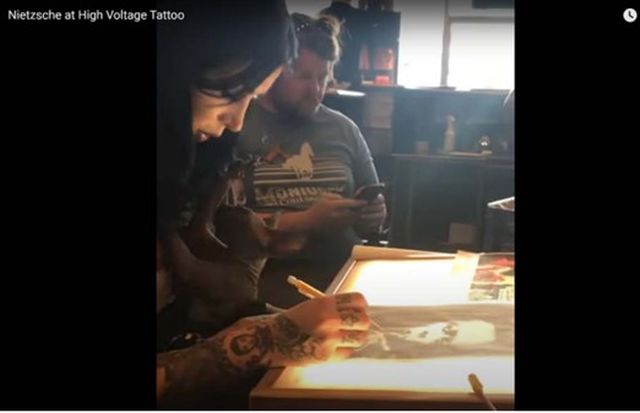

Kat von D using the portrait to trace the tattoo. Screenshot from Complaint.

Kat von D shared the tattoo on both her Instagram page and the Instagram page associated with her tattoo studio, High Voltage Inc. The social media posts showed Kat von D using the original portrait to trace the design that she would later tattoo on Farmer's arm. The posts also depicted an image of Kat von D hanging the portrait on her wall for use as a future reference during the inking process.

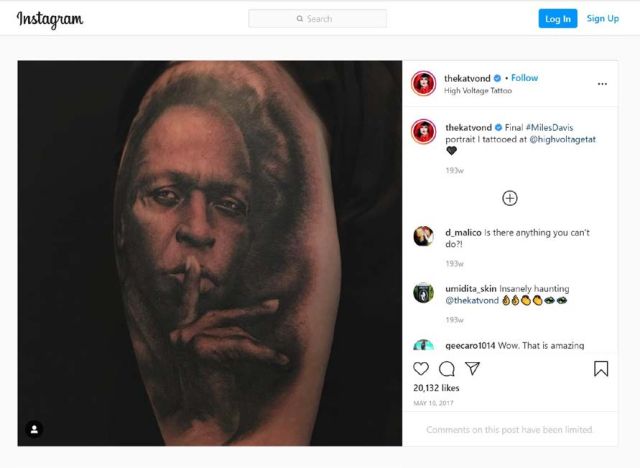

Kat Von D's Miles Davis tattoo, as shared on High Voltage's Instagram page. Screenshot from Complaint.

Procedural History

On February 7, 2021, Sedlik brought a claim for copyright infringement against Kat von D in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. Since it was clear from her social media posts that she had traced Sedlik's work to create the tattoo, Sedlik's main burden was to prove that Kat von D's work was substantially similar to his. Kat von D raised several arguments in her defense, including the affirmative defense of fair use.

To determine substantial similarity, the Ninth Circuit requires a plaintiff to prove similarity under both "extrinsic" and "intrinsic" tests. The extrinsic test is an objective comparison of specific expressive elements, while the intrinsic test is a subjective comparison that focuses on whether the ordinary, reasonable audience would find the works similar in their "total concept and feel." However, even if the plaintiff shows substantial similarity, the defendant's actions may still be excused under the fair use doctrine, which exempts certain copying from infringement liability on a case-by-case basis based on several factors provided in 17 U.S.C. § 107.

In March 2022, the parties cross-moved for summary judgement. Sedlik claimed that both the tattoo and the social media posts featuring his original portrait in the background were substantially similar to his portrait and therefore constituted copyright infringement. Sedlik alleged that he profits from the photograph through licensing agreements. Therefore, Sedlik argued, Kat von D should have sought a licensing agreement to make a tattoo based on his work.

Kat von D's summary judgment motion was based on an argument that the tattoo, as applied to Farmer, met the requirements for a fair use defense "because it is imbued with a new expression, meaning or message that is particular to Mr. Farmer. By having this image permanently imprinted on his body, Farmer intended to evoke personal memories of his college years studying jazz, and the personal significance to him of Miles Davis, with whom he shares a 'rebellious spirit.'" Kat von D argued that the inherently transformative nature of tattoos shields tattoo artists from liability.

The court denied Sedlik's summary judgment motion as to copyright infringement liability and also denied Kat von D's motion as to fair use, finding that a trial was necessary to determine both whether Kat von D's work was substantially similar to Sedlik's and whether it qualified for a fair use defense.

However, on November 21, 2022, before trial could commence, the court issued a temporary stay pending resolution of the Supreme Court case Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. 508 (2023). The Warhol case was directly pertinent to Kat von D's claims about the transformative character of her tattoo because the parties in Warhol sought clarification of the first prong of the fair use test, which evaluates "the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature[.]" 17 U.S.C. § 107.

The issue in Warhol was whether the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF)'s decision to license one of Warhol's Prince Series images—a set of silkscreen prints authored by Andy Warhol and derived from Lynn Goldsmith's photograph of the singer-songwriter Prince—constituted fair use. On May 18, 2022, the Court held that there was no fair use. (You can read more about the Warhol decision in our article "SCOTUS: Fair Use Defense Fails to Protect Warhol's Licensing of Orange Prince").

Following the Supreme Court's decision in Warhol, Sedlik and Kat von D petitioned the district court for reconsideration of its summary judgment order. In October 2023, the court determined that Warhol was relevant and updated certain aspects of its summary judgment order to conform to the principles established by the Supreme Court. Specifically, the court held that Kat von D had not produced evidence that the tattoo was transformative because her reliance on formal analysis of the tattoo's aesthetic character was foreclosed by Warhol. Nevertheless, the court still determined that triable issues of fact remained as to fair use with regard to both the tattoo and the social media posts. And the court further held that Warhol had no influence on its previous holding that there remained a triable issue as to the substantial similarity between the Davis portrait and the alleged infringements.

Trial

Trial began on January 23, 2024. According to courtroom reports, on the issue of substantial similarity, Sedlik's counsel argued in closing that a side-by-side comparison of the photograph and tattoo revealed them to be nearly identical works, barring the differences in medium of expression. Kat von D's attorney used a similar side-by-side comparison to make the opposite point, emphasizing that her tattoo was an artistic interpretation of the photograph reflecting her artistic choices. In recreating the image for Farmer's arm, Kat von D altered the lighting to make it visible on Farmer's skin, rendered the lighting more uniform, added shading to soften the perimeter of the portrait, and changed other details to alter the perception of movement evoked by the tattoo. Kat von D's counsel explained that these differences should lead the jury to conclude that the works are not substantially similar under the extrinsic test, but they also add up to a tattoo that is different in composition and overall feel from Sedlik's photograph under the intrinsic test. In Kat von D's own words, she is "not a copy machine."

On the issue of fair use, Kat von D's trial team attempted to convince the jury that her tattoo should be deemed transformative as reflecting her own artistic designs. Under the first fair use factor, a work serves a transformative purpose when it "adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message." Of course, the Supreme Court did not hold Warhol's silkscreen print to be fair use even though it was artistically transformative because it shared a commercial purpose with Goldsmith's original copyrighted photograph. According to courtroom reports, in her testimony, Kat von D sought to differentiate herself from "a mass-produced magazine that, you know, you're selling thousands of units based off somebody's artwork," explaining that "I'm not mass-producing anything or gaining any monetary value." She underlined that the tattoo did not face Warhol's same-commercial-purpose problem because she provided the tattoo for free, and it was therefore non-commercial.

Both sides also sought to address the fourth prong of the fair use test, which concerns "the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work." 17 U.S.C. § 107. Sedlik's trial team advanced the argument that the Copyright Act should be interpreted to protect a hypothetical market for licensing images to tattoo artists. Although, in his testimony, Sedlik could not identify an existing market for licensing copyrighted images to tattoo artists who sought to ink them, he did point to numerous instances where other artists had paid him reference licenses to create derivate works. He estimated that one licensing agreement he had reached with a painter had earned him as much as $100,000. Sedlik's counsel argued that the tattoo industry should not be treated differently from other creative industries in which users compensate copyright holders for permission to create derivative works.

According to courtroom reports, Kat von D testified that, to the contrary, there is something inherently different about the customs and norms of the tattoo industry. "Nobody asks for permission" to use other people's works, she said of tattoo artists, explaining that she had recreated tattoos made by other tattoo artists as well. "It's fan art. That's what we do. That's all tattooing is." Kat von D's attorneys argued that, without a potential market to point to, Sedlik's claim of harm was merely speculative.

The jury returned a verdict for Kat von D, finding that she did not infringe Sedlik's portrait because the works were not substantially similar. In light of this finding, the jury had no need to resolve the question of whether the tattoo constituted fair use.

The jury did, however, need to address the fair use defense in connection with Kat von D's social media posts featuring the Miles Davis portrait, such as the image of Kat von D tracing it. The jury found that these posts were indeed protected by the fair use doctrine and entered a verdict for Kat von D on that ground.

Impact and Implications

While the jury returned a victory for Kat von D, its verdict fell short of delivering a victory to the tattoo industry at large. By finding that the two works in question were not substantially similar, the jury avoided reaching the potentially broader question of fair use in the context of the tattoo market as Kat von D had described it. The case therefore leaves open various questions, including whether tattoo art is transformative due to its inherent nature, whether tattoo industry norms akin to "fan art" would preclude a finding of harm to a potential licensing market for copyrighted inspiration works, and whether a tattoo artist who charged for her work might be found liable even if an artist working for free would not. Given the proliferation of lawsuits involving tattoos in recent years, other courts may find occasion to address these questions in the future.

The case is Sedlik v. von Drachenberg et al, No. 2:21-cv-01102, C.D. Cal. 2024.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.