- within Government, Public Sector, Environment and Technology topic(s)

In May, the Supreme Court issued a narrow decision on the issue of fair use in copyright infringement cases. The case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, strengthened the position of potential plaintiffs – a little.

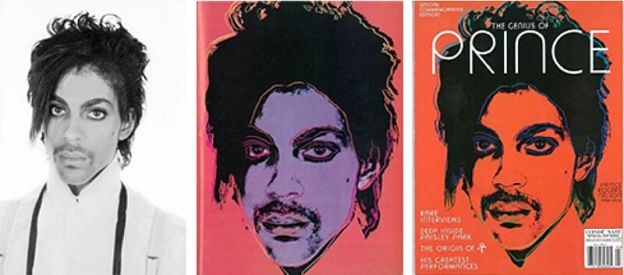

The artist Andy Warhol had used a copyrighted photograph of the musician Prince to create one of his signature stylized images. At issue was whether that use infringed the photographer's rights, or whether Warhol's work was sufficiently "transformative" to be considered a fair use, preventing liability for infringement of the underlying photograph. It generated a spirited back-and-forth between the majority and dissenting opinions, but the majority held in favor of the photographer and against the Warhol Foundation's defense of fair use.

Lynn Goldsmith is a prominent photographer, particularly of rock-and-roll musicians. She took photographs of Prince in 1981, when he was a little-known musician. In 1984, Vanity Fair magazine was preparing a story about Prince and engaged Warhol to create an illustration for the article based on one of Goldsmith's images from the 1981 session. Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith $400 for a one-time license to allow Warhol to use her photograph and to publish it in the magazine. Warhol made various changes to the photograph – cropping it, slightly rotating it, and rendering it in a high-contrast format – and created a silk screen version, which he used as a basis for a series of 14 variations with different added colors and effects. Vanity Fair chose one of those images, showing Prince with a purple face with some additional flourishes added by Warhol.

Years later, after Prince died, the magazine publisher Condé Nast wanted to use a different one of Warhol's "Prince Series" images in a commemorative edition. The Warhol Foundation, which owned Warhol's rights in the works after Warhol's death, granted Condé Nast a license to use a version showing the altered Goldsmith photograph with orange color and other additions. Condé Nast paid the Foundation $10,000 for that use. Goldsmith got nothing. She objected, and the Foundation sued her, seeking a judgment that Warhol's use was a "fair use" of the underlying image.

Goldsmith's original and Warhol's purple and orange versions, as shown in the Supreme Court's decision.

Fair use is a defense to copyright infringement that allows the re-use of copyrighted material without liability. Typically it applies where the copyrighted work is used in a way that is sufficiently different from the original that it would be unlikely to usurp the market for the original: classic fair uses are such things as use of portions of the original in criticism or in academic works. The fair use defense provides a "safety valve" to avoid liability when a rigid application of the Copyright Act would stifle the creativity that copyright law is intended to foster.

The Copyright Act sets out four factors for a court to consider in determining whether a use is "fair." The four factors are weighed against each other in making the fair use determination, and while no single factor necessarily overrides the others, the fourth – the likely market effect of the allegedly infringing use – is typically a particularly important consideration. Others may be more or less important depending on the facts of the particular case.

The District Court held that Warhol's use was sufficiently "transformative" that all of the fair use factors favored Warhol. The Court of Appeals reversed, holding that all four factors favored Goldsmith.

At the Supreme Court, the Foundation only challenged the Court of Appeals' finding on the first factor, the "the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes." The Foundation's argument, which the dissenting opinion adopted, was that Warhol so transformed the original photograph that Warhol's work is, in effect, a completely different work and should not be considered an infringement – in terms of the first factor, the argument is that the original work's "character" has been fundamentally altered.

That argument has been accepted in the case of parodies, such as in a 1994 Supreme Court case involving 2 Live Crew's ribald adaptation of Roy Orbison's song, "Oh, Pretty Woman." The Foundation based its argument on the idea that the Warhol version conveyed a totally different meaning than the original, showing Prince as an iconic figure rather than the vulnerable young artist shown in Goldsmith's original. As a result, it argued, the "character" of the use was so changed that the first factor favored fair use.

An important consideration is that the Copyright Act grants the copyright owner the exclusive right to do a number of things with the copyrighted work, including the right to prepare (or to allow others to prepare) "derivative works." A derivative work is one "based upon one or more preexisting works," such as an adaptation of a book into a play or movie, a sound recording of a song, "or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted." The Court wrote that to preserve the exclusive right to make derivative works while accommodating fair use for "transformative" works, the fair use defense must be limited to those works that have been so transformed as to go beyond the transformation that constitutes a derivative work. Otherwise the fair use defense could swallow the owner's exclusive right over derivative works.

The Court clarified the analysis by holding that the first factor considers how the copier used the original work. If the original work and the secondary work are used for the same or very similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial in nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use unless there is some strong justification for the copying, such as where the second work is commentary, criticism, or parody.

Under this framework, the specific way the copier is using the original work is critical. The only use at issue in this case was the Foundation's licensing of the "Orange Prince" image to Condé Nast for use in a magazine about Prince – which was the very type of use for which Goldsmith often licensed her own photographs. Warhol himself had originally used Goldsmith's photograph under such a license.

The Court held that for purposes of the fair use analysis, the Foundation's use was for substantially the same purpose as Goldsmith's photograph, even though the two works were not perfect substitutes. The licensing was commercial in character, which weighed against fair use.

The Foundation argued for a different interpretation of the "purpose and character of the use." It argued that the purpose and character of its use was different from the original Goldsmith photograph, and was transformative for fair use purposes, because while Goldsmith's photograph showed a vulnerable young artist, Warhol's Prince image showed him as "iconic" and was a comment on the "dehumanizing nature of celebrity."

The Court rejected the idea that Warhol's addition of new expression, meaning, or message made his work transformative, because otherwise fair use would erase the author's exclusive right to prepare derivative works. Derivative works, it noted, commonly add new expression, meaning, or message – but they still require a license. It is not enough to say that the secondary work is transformative because it is a worthy piece of art, or, as in this case, "It's a Warhol." Otherwise certain artists would be granted a privilege to use others' work. Nor is the intent of the author of the secondary work sufficient to make it transformative. The question is objective: how the secondary user used the original work.

The purpose of Condé Nast's use of Orange Prince was to illustrate a magazine about Prince. Because that use was so similar to the way the original photograph is typically used, the Foundation would have to provide a "particularly compelling justification" for the unlicensed use, and the desire to "convey a new meaning or message" is not enough.

Without any justification for unauthorized use of the Goldsmith photograph, the first fair use factor weighed in favor of Goldsmith and against fair use. Because the Foundation did not challenge the determinations that the other factors all favor Goldsmith, the Court affirmed the judgment of the Court of Appeals.

The decision should help to avoid making the fair use analysis any more difficult and unpredictable than it inevitably is. The dissenting opinion arguably reads more like an art-history paper than a legal opinion, and the majority was wise to avoid turning copyright infringement cases into disputes about the meaning of creative works, particularly works of visual art whose meaning is very much in the eye of the beholder.

The dissent had two main points: that the Warhol work takes on a different meaning from the original, and that all art includes some degree of borrowing from what has come before. Those may both be true, but they do not require the conclusion that the Foundation's use was fair or that allowing such borrowing without compensation to the author of the original work is required to advance artistic creativity. The idea embodied in the Constitution and the Copyright Act is that we encourage creativity by granting the author exclusive rights to certain uses of the work (and, as a result, the right to demand payment if someone else wants to use that work). An overly broad application of the fair use doctrine would undercut that incentive. The Court wisely rejected that outcome.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.