- in United States

- within Law Department Performance, Accounting and Audit and Law Practice Management topic(s)

Duane Morris Takeaway: Continued settlements in the privacy space have inspired more members of the plaintiffs' bar to make privacy litigation the centerpiece of their business models. Although the landscape has shifted over the past five years, the recipe has remained similar — combine archaic statutory schemes, which provide for lucrative statutory penalties, with a ubiquitous technology, to yield the threat of a potential business-crushing class action that can be made via widespread use of form letters and cookie-cutter complaints, to generate payouts on a massive scale.

Watch Class Action Review co-editor Jennifer Riley explain this trend in the following video:

Privacy continued to dominate as one of the hottest areas of growth in terms of class action filings by the plaintiffs' bar in 2025.

As noted, the landscape has shifted over the past five years. In 2023, many plaintiffs' attorneys targeted session replay technology, which captures and reconstructs a user's interaction with a website, or website chatbots, which are programs that simulate conversation through voice or text, or biometric technologies, which capture traits like fingerprints or facial scans for purposes of identification.

Over the past two years, the focus for many plaintiffs' class action lawyers has shifted to website pixels – pieces of code embedded on websites to track activity and, in some circumstances, to provide information about that activity to third-party social media and analytics providers. Plaintiffs have launched thousands of claims via form letters, cookie-cutter complaints, and mass arbitration campaigns.

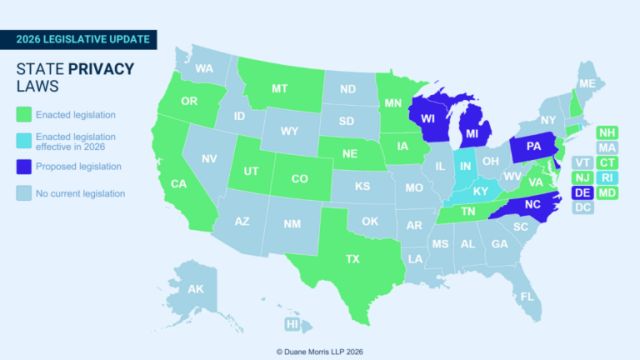

In 2025, while plaintiffs pulled back on filings in areas like biometric privacy, we saw a surge in litigation over internet tracking technologies based on a patchwork quilt of state-level laws, including the California Invasion of Privacy Act ("CIPA").

1. Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act ("BIPA") Claims

Following steep year-over-year growth between 2017 through 2024, companies that operate in Illinois finally saw a reprieve from the growth in BIPA litigation in 2025. The BIPA was once one of the most popular privacy laws in the United States. On August 2, 2024, however, the Illinois Governor signed a long-awaited amendment to the BIPA that eliminated "per-scan" statutory damages in favor of a "per-person" model. Over the past year, the impact of this amendment became apparent as the plaintiffs' class action bar shifted its attention away from the BIPA and toward potentially more lucrative statutory schemes.

Enacted in 2008, the BIPA regulates the collection, use, and handling of biometric information and biometric identifiers by private entities. Subject to certain exceptions, the BIPA prohibits collection or use of an individual's biometric information and biometric identifiers without notice, written consent, and a publicly available retention and destruction schedule.

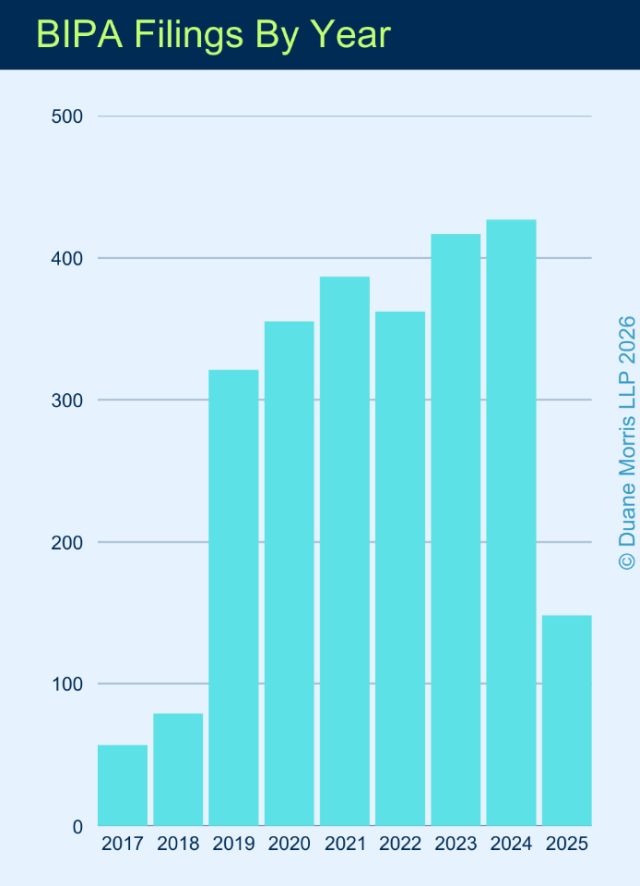

For nearly a decade following enactment of the BIPA, activity under the statute remained largely dormant. The plaintiffs' bar filed approximately two total lawsuits per year from 2008 through 2016 before filings increased in 2017 and then skyrocketed in 2019. In 2020, plaintiffs filed more than six times as many class action lawsuits for alleged violations of the BIPA than they filed in 2017 and more than the number of class action lawsuits they filed from 2008 through 2016 combined.

Filings continued to accelerate in 2023, prompted by two rulings from the Illinois Supreme Court that increased the opportunity for recovery of damages under the BIPA. On February 2, 2023, the Illinois Supreme Court held that a five-year statute of limitations applies to claims under the BIPA, and, on February 17, 2023, the Illinois Supreme Court held that a claim accrues under the BIPA each time a company collects or discloses biometric information. See Tims v. Black Horse Carriers, 2023 IL 127801 (Feb. 2, 2023); Cothron v. White Castle System, Inc., 2023 IL 1280004 (Feb. 17, 2023). BIPA-related filings jumped markedly in the months following these rulings.

In 2024, the Illinois General Assembly abrogated Cothron. On August 2, 2024, the Illinois Governor signed SB 2979 into law, which amended the BIPA and clarified that plaintiffs are limited to one recovery per person under §§ 15(b) and 15(d). In other words, a private entity that, in more than one instance, collects, captures, or otherwise obtains the same biometric identifier or biometric information from the same person using the same method of collection "has committed a single violation" for which an aggrieved person is entitled, at most, to one recovery. See 740 ILCS 14/20 (b), (c).

In a welcome relief for defendants, within a year after the BIPA's new "per person" damages regime took effect, we saw a substantial drop in filings. Whereas their rate of growth slowed in 2024, BIPA-related filings remained robust in 2024 in comparison with prior years. In 2025, however, filings declined by a substantial margin. Plaintiffs filed only 150 lawsuits invoking the BIPA in 2025, compared with 427 lawsuits in 2024, 417 in 2023, and 362 in 2022.

The graphic shows the number of BIPA-related filings over the past eight years, including the year over year growth, followed by the substantial drop off in 2025. The rapid drop in BIPA-related filings suggests that damages available under other, perhaps more widely applicable and/or more generous per-violation statutes proved a more attractive lure to the plaintiffs' class action bar in 2025.

2. Website Advertising Technology

Although website activity tracking tools are nothing new, and appear on most websites, this past year they continued to fuel a growing wave of lawsuits alleging that such tools caused companies in various industries to share users' private information. In 2025, plaintiffs filed thousands of class action complaints – and served many more demand letters – alleging that companies had software code embedded in their websites that secretly captured plaintiffs' data and shared it with Meta, Google, or other online advertising agencies.

Advertising technology, often called "adtech," broadly describes the software and tools that advertisers use to reach audiences and to measure digital advertising campaigns. Adtech enables advertisers to track customers' online behaviors so that they can shape advertising content. Advertisers rely on adtech to inform decisions on who to target, how to present information, and how to track success.

Plaintiffs have asserted claims attacking adtech based on one or more of a wide variety of statutes and legal theories, such as the Video Privacy Protection Act ("VPPA"), the Electronic Communications Privacy Act ("ECPA"), as well as state specific statutes such as the California Invasion of Privacy Act ("CIPA"). Many of the statutes that plaintiffs seek to invoke predate the technology by multiple decades, forcing courts to attempt to apply them to technologies that the drafters never contemplated, leading to a patchwork quilt of divergent outcomes.

Plaintiffs typically seek to invoke a statute that provides for statutory damages, asserting that hundreds of thousands of website visitors, times $10,000 per claimant in statutory damages under the Federal Wiretap Act, for example, or that hundreds of thousands of website visitors, times $5,000 per violation in statutory damages under the CIPA, equals billions of dollars in supposed damages.

Certain members of the plaintiffs' class action bar have constructed business models designed to efficiently leverage such allegations. After identifying any of millions of websites with adtech, they generate form or templated demand letters asserting violations of the CIPA or other statutes based on the use of tracking technologies provided by companies such as TikTok, LinkedIn, X, or others. They slow-play any formal filing, with the goal of leveraging a quick settlement and avoiding investment of fees and costs.

This repeatable formula is fueled by settlement dollars and dependent on continued disagreement among courts on basic attributes of these claims. This past year plaintiffs asserted such claims under various statutes and common law theories. While claims under the VPPA encountered roadblocks, court rulings in other areas showed more promise, driving claims toward statutes like CIPA.

A. The VPPA

In cases where websites allegedly transmit video viewing

information, plaintiffs often assert claims for alleged violations

of the federal VPPA. The statute prohibits a "video tape

service provider" from knowingly disclosing "personally

identifiable information concerning any consumer of such

provider." 18 U.S.C. § 2710(b)(1).

The statute defines a "video tape service provider" to include any person "engaged in business, or affecting interstate or foreign commerce, of rental, sale, or delivery of prerecorded video cassette tapes or similar audio-visual materials." 18 U.S.C. § 2710(a)(4). The VPPA provides for damages up to $2,500 per violation in addition to costs and attorneys' fees for successful litigants, making it an attractive source of filings for the plaintiffs' class action bar.

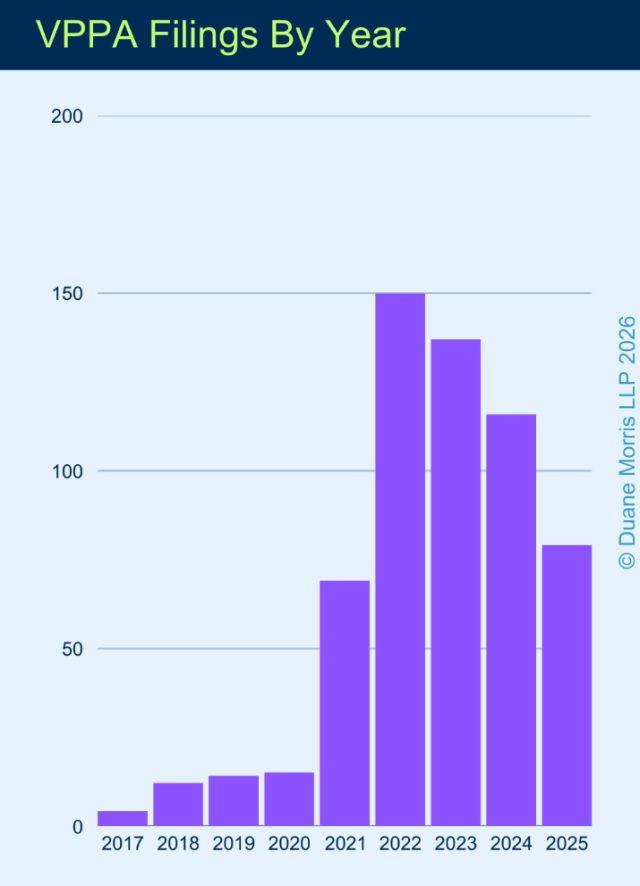

Reflecting its comparatively narrower scope, Plaintiffs filed fewer VPPA class actions in 2025, compared to 116 VPPA class actions in 2024, and 137 in 2023, fueled in large part by adtech claims.

In 2025, many defendants succeeded in dismissing VPPA claims at the outset, particularly in the Second Circuit, which surely depressed filings in this area. Solomon v. Flipps Media, Inc., 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 10573 (2d Cir. May 1, 2025), is a prime example. In that case, the Second Circuit applied a narrow reading of the VPPA, holding that the statute protects against only those disclosures that an ordinary person could use to identify a consumer's video-viewing history. The plaintiff, a subscriber to Flipps Media's streaming platform, alleged that each time she watched a video on the platform, Flipps transmitted to Facebook, via the Facebook Pixel, an encoded URL identifying the video and her unique Facebook ID (FID) in violation of the VPPA. The district court dismissed the complaint reasoning that, although Flipps transmitted data to Facebook, the plaintiff had not shown that her Facebook ID, even when paired with a video URL, would enable an ordinary person to identify her or her video-viewing behavior. On appeal, the Second Circuit affirmed. The Second Circuit emphasized that Congress intended to prevent disclosures that an average person, "with little or no extra effort," could use to link an individual to specific video content. Id. at *27. The data Flipps transmitted was embedded in a mass of technical code and unreadable to a layperson.

Whereas such rulings had a muting effect on filings, courts in other jurisdictions applied different standards, signaling some continued daylight for the VPPA to fuel claims. In Manza, et al. v. Pesi, Inc., 784 F. Supp. 3d 1110 (W.D. Wis. 2025), for instance, the plaintiff purchased videos from Pesi, Inc. and she brought a putative class action alleging that Pesi disclosed her purchasing history and unique identifiers (e.g., Facebook ID, Google/Pinterest client or user IDs, hashed emails, IP addresses) to third-party ad platforms and data brokers via tracking technologies (Meta Pixel, Google Analytics/Tag Manager, Pinterest Tag) without her consent in violation of the VPPA. Pesi moved to dismiss arguing that: (i) it is not a "videotape service provider" under the VPPA (citing its nonprofit status); (ii) the data disclosed is not "personally identifiable information" within the meaning of the statute; and (iii) Manza's factual allegations were insufficient to satisfy federal pleading standards. Id. at *2-3. The court denied the motion. It held that, at the pleading stage, it was reasonable to infer that Pesi is a "videotape service provider" because it regularly sold videos on its website. Id. at *5. The court held that unique identifiers tied to a specific account (e.g., Facebook ID, client/user IDs) qualify as personally identifiable information under the VPPA when paired with video titles the customer obtained from the defendant. Finally, the court rejected the "ordinary person" test (and decisions adopting it), reasoning that the VPPA's text and purpose support a broader reading that covers identifiers capable of being used to trace a customer's video purchases.

B. The CIPA

Companies that operate websites frequented by California consumers have received a wave of demand letters threatening claims under the CIPA, many of which have matured into lawsuits and arbitration proceedings. The CIPA presents an attractive option for plaintiffs because it offers statutory damages of $5,000 per violation, making it one of the most, if not the most, generous damages schemes provided by any privacy law.

California passed the CIPA, a criminal statute, in 1967 to prevent unlawful wiretapping to eavesdrop on telephone calls. Among other things, the CIPA prohibits use of pen registers and "trap and trace" devices without either a court order or explicit consent. The CIPA defines a pen register as "a device or process that records or decodes dialing, routing, addressing, or signaling information" for outgoing communications, and it defines a trap-and-trace device as a surveillance tool that captures similar information for incoming communications.

Plaintiffs frequently allege that website tracking technologies, such as cookies and pixels, run afoul of the CIPA because they permit companies to acquire identifying information about website visitors, such as their phone numbers and email addresses and other personal information. In the past few years, plaintiffs have filed hundreds if not thousands of cases attacking various types of widely used website technologies. While plaintiffs have filed many lawsuits alleging violations of the CIPA, they have sent many more demand letters that resulted in arbitration or pre-lawsuit settlements.

Inconsistency in the case law continues to fuel these claims. Taking a recent example, in Camplisson, et al. v. Adidas, Case No. 25-CV-603 (S.D. Cal. Nov. 18, 2025), the plaintiff, a website visitor, claimed that the sportswear company used pixels on its website that collected private information from visiting consumers.

The court denied the motion to dismiss. The court held that the plaintiff sufficiently alleged that the trackers on Adidas' website collected a "broad set" of personal identifying and addressing information and thus alleged a concrete harm in the loss of control of their own information. The court also held that the plaintiff sufficiently alleged that such web-based trackers plausibly qualify as pen registers and that users did not effectively consent because the website did not make its terms conspicuous and did not provide a mechanism for affirmative assent.

The ruling runs counter to other decisions and thus contributes to the patchwork quilt of rulings in this area. For instance, among other thing, the court distinguished the Ninth Circuit's ruling in Popa, et al. v. Microsoft Corp., 153 F.4th 784, 786, 791 (9th Cir. 2025), from earlier this year.

It explained that Popa addressed a claim concerning the defendant's use of session-replay technology, which collected information on what products the plaintiff browsed and where her mouse hovered while on the website, and thus concerned how the plaintiff interacted with the website rather than her personal, private information.

The ruling also failed to account for Price, et al. v. Converse, Case No. 24-CV-08091 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 30, 2025), where another district court considered similar allegations and reached a different conclusion. The plaintiff alleged that the TikTok pixel engages in "device fingerprinting" to collect data about visitors to the Converse website including browser information, geographic information, and referral tracking information. The court found the plaintiff's allegations insufficient to establish a "concrete injury" as required for standing because the plaintiff failed to plead any kind of harm that is remotely like the 'highly offensive' interferences or disclosures that were actionable at common law.

On June 3, 2025, the California Senate unanimously passed Senate Bill 690 (SB 690), which would have amended the CIPA on a prospective basis by providing a "commercial business purpose" exception. The bill defined "commercial business purpose" as the processing of personal information either to further a business purpose, as defined in the CCPA, or when the collection of personal information is subject to a consumer's opt-out rights under the CCPA.

The California Assembly, however, later placed SB 690 on hold, classifying it as a two-year bill, meaning that its earliest reconsideration would occur in 2026, if at all, and its future is uncertain.

Thus, without a legislative response, the continued variation among courts in their approaches to these claims is likely to continue to fuel uncertainty and, as a result, both claims and settlements in this area. An expansive discussion of the vast and growing patchwork quilt of differing approaches to adtech claims appears in Chapter 14 regarding Privacy Class Actions.

Disclaimer: This Alert has been prepared and published for informational purposes only and is not offered, nor should be construed, as legal advice. For more information, please see the firm's full disclaimer.

[View Source]