- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- in United States

- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- within Law Department Performance, Accounting and Audit and Law Practice Management topic(s)

Duane Morris Takeaway:This week's episode of the Class Action Weekly Wire features Duane Morris partner Jerry Maatman and senior associate Nelson Stewart with their analysis of key developments in securities fraud class actions, including a notable decision from the U.S. Supreme Court clarifying the standard for claims brought under the Securities Exchange Act alleging pure omissions of fact.

Check out today's episode and subscribe to our show from your preferred podcast platform: Spotify, Amazon Music, Apple Podcasts, Samsung Podcasts, Podcast Index, Tune In, Listen Notes, iHeartRadio, Deezer, and YouTube.

Episode Transcript

Jerry Maatman: Thank you for being here again, loyal blog listeners and readers, for the next episode of our weekly podcast series, the Class Action Weekly Wire. I'm Jerry Maatman, a partner at Duane Morris, and joining me today is Nelson Stewart from our New York office. Thanks so much, Nelson, for being on the podcast.

Nelson Stewart: Thank you. Great to be here, Jerry.

Jerry: Today we want to discuss trends and important developments in the securities fraud class action space. Certainly, securities fraud claims generally turn on alleged public misrepresentations by a security issuer and adjudication of these claims often are done on a class-wide basis. The plaintiffs' bar obviously has made class action litigation in the securities fraud space a very active area, and 2024 was certainly no exception. Nelson, can you explain to our listeners a little bit of the background of how federal securities laws work in this context?

Nelson: Sure, the pillars of the federal securities law are the Securities Act of 1933, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, both of which were enacted in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929 to help regulate the securities markets and promote transparent disclosure to investors. The Securities Act generally regulates securities offerings, while the Securities Exchange Act governs the trading of existing securities and securities markets. The Securities Act allows private litigants to pursue claims against corporate issuers for material misrepresentations or omissions made in connections connection with the securities offering. Although the Securities Act expressly provides a private cause of action, for losses related to an offering a plaintiff must demonstrate the shares of the security at issue trace back to that offering. Because of this limitation, plaintiffs tend to look to the broader implied right of right of action under the Securities Exchange Act Section 10(b) and SEC Rule 10b-5, which prohibit fraudulent schemes and fraudulent misrepresentations in connection with any securities transaction.

Jerry: Well, thanks so much for that context. In the class action space, securing class certification is the Holy Grail for the plaintiffs' bar because it's very dangerous to try a certified class action. And so, the parties put lots of effort into either prosecuting or opposing a motion for class certification. And that in turn requires that questions of law or fact predominate over those that are pertinent to individuals, and that a class action is superior to all of their methods to adjudicate the dispute. In the securities fraud context, what are some of the challenges and litigations in terms of securing or defending against class certification?

Nelson: For a large and varied group of plaintiffs, proving reliance on a misstatement of material fact – which is one of the prerequisites of a securities fraud action – often creates individual fact issues among investors that could overwhelm common fact issues and present an insurmountable hurdle to class certification. This challenge was substantially mitigated when the U.S. Supreme Court adopted the "fraud on the market theory" of reliance in Basic v. Levinson. This theory avoids the need to show individual alliance by employing the presumption that, when a stock trades in an efficient market, investors "rely on the market as an intermediary for setting the stock price in light of all publicly available information; accordingly, when an investor buys or sells the stock at the market price, the investor has, in effect, relied on all publicly available information, regardless of whether the investor was aware of that information personally."

Jerry: How does the plaintiff's bar invoke the Basic presumption to be able to litigate securities fraud class actions?

Nelson: To invoke the Basic presumption, plaintiffs must demonstrate that a misrepresentation was publicly known; that it was material; that the stock traded in an efficient market; and that the plaintiffs traded the stock between the time the misrepresentation was made and the date the misrepresentation was revealed to be untrue.

Jerry: Well, I know a lot of cases and rulings in 2024 pivoted on that presumption. In your mind, what were some of the key rulings in the past 12 months?

Nelson: In 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court clarified the standards for claims brought under the Exchange Act that allege a pure omission of fact. In Macquarie Infrastructure Corp., et al. v. Moab Partners, L.P., plaintiffs alleged Macquarie omitted material facts and public statements, but did not identify any material misleading statements of fact made by Macquarie. Under the Securities Act, a pure omission of fact is expressly prohibited if it makes the statement in an offering document misleading. The Supreme Court held that Macquarie's pure omission did not impose liability under Rule 10b-5, even when there is a duty to disclose, unless they render the affirmative statement misleading. In this case, plaintiffs had not alleged any affirmative misstatement. The decision also resolved a split among the courts of appeal concerning private right of action, arising from an Item 303 statement issued pursuant to SEC Regulation S-K. Item 303 statements require a publicly held company to disclose trends and uncertainties that affect the company's financial condition. The Supreme Court ruled that, half-truths, in which a defendant discloses some, but not all, material facts that render the statement misleading can create liability for an Item 303 statement. However, a pure omission, as in this case, in an Item 303 statement does not create a private right of action. Other notable decisions discuss the reasonable investor standard established by the Supreme Court in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industries Pension Fund and the presumption for omissions under Rule 23 set forth in the Supreme Court's decision in Affiliated UTE Citizens v. United States.These cases were addressed in In Re Ocugen, Inc. Securities Litigation, and in Crews, et al. v. Rivian Automotive, Inc.

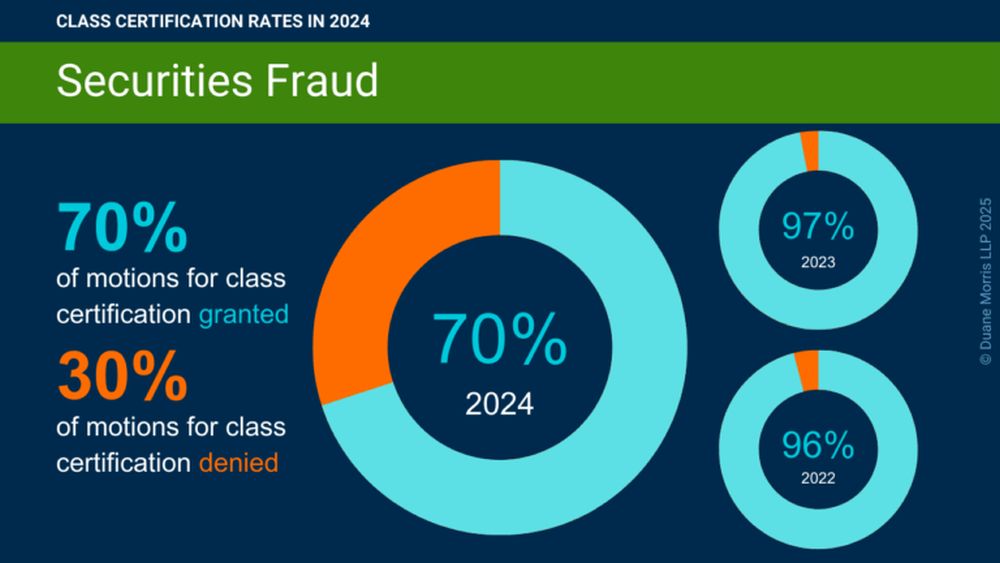

Jerry: It's like the plaintiffs' bar in the securities fraud class action area is constantly pushing the legal envelope and innovating with new theories. How successful was the plaintiffs' bar in 2024 in securing certification of motions for class certification?

Nelson: In 2024, 70% or 19 out of 27 class certification motions in securities fraud actions were successful. Defendants fared better on motions to dismiss, motions to strike, and motions for summary judgment, which were granted in whole or in part at a fairly high rate.

Jerry: That is a high rate. Do you have a sample, in terms of your thinking, of what class certification ruling kind of crystallizes all this, and is representative of victories on the plaintiff side?

Nelson : In Pampena v. Musk, plaintiffs filed a class action under 10(b) of the Exchange Act alleging Elon Musk made misleading statements to artificially depress the share price of Twitter, after Musk announced his intention to acquire the company. In April 2022, Twitter agreed to be acquired by an entity that was wholly owned by Musk for $54.20 per share. From May 14, 2022, to May 17, 2022, Musk made three public statements concerning the anticipated acquisition. First, Musk stated that the merger was on hold because the presence of fake accounts and spam on the Twitter platform would prevent him from completing the acquisition. Musk followed that comment by stating that these accounts comprise more than 20% of Twitter users. Finally, Musk announced that the merger could not move forward until Twitter's CEO issued accurate SEC statements after the CEO declined to publicly disprove Musk's claims about the fake accounts. Plaintiffs alleged that the share price dropped from $45.08 on May 12 to $35.76 by May 24. In opposition to the motion for class certification, Musk did not dispute the numerosity requirement or the commonality requirements of Rule 23. His opposition focused primarily on the predominance requirement of Rule 23(b)(3). Musk argued that the sophisticated investors would have understood that his statements were false and would not have relied on them. Accordingly, the class could not show individual reliance among the sophisticated investors and the other investors in the class. The court noted that the plaintiffs asserted their claims under the fraud on the market theory of reliance adopted by the Supreme Court in Basic. In challenging the fraud on the market theory, Musk argued the difference between sophisticated investors and other investors in the class rendered the market for Twitter shares inefficient. The court found that this argument misplaced the emphasis on investors. The fraud on the market theory presumes that in an efficient market, all publicly available information, not an investor's interpretation of that information, is deemed to be reflected in the share price. Once the Basic presumption is established, predominance is satisfied, absent a rebuttal of the price impact caused by the misrepresentation. The court found that Musk had not presented any evidence that would sever the link between his misrepresentations and the decline in share price that is required to rebut the basic presumption. Musk also argued that the lead plaintiffs were not typical of those in other of other class members, because there were certain class members who did not rely on his statements. The court found this argument similar to the predominance defense and held that the lead plaintiff's experience reflected common issues among the plaintiffs, and that the claims were sufficiently typical. Finally, Musk argued that the class was overbroad because it would include individuals who either did not realize a loss or profited from the trades within the class period. The court ruled that a subset of class members who did not incur damages does not defeat a class action at the certification stage. It reasoned that injured parties and non-injured parties should be sorted out in the damages phase of the litigation, and the court granted the plaintiff's motion for a class certification.

Jerry: That last point is interesting. Yesterday morning, the U.S. Supreme Court issued an 8-to-1 ruling in LabCorp v. Davis and indicated that certiorari had been improvidently granted. But Justice Kavanaugh issued a dissent – and this is a class action case that many people were following – where he indicated that if a class contains uninjured class members, a district court cannot certify it, and it's not something in the damages phase. Obviously, it's just one vote. It's in a dissent. But, when a Supreme Court Justice dissents like that, it's very important. So, it will be interesting to see if there's a motion for reconsideration brought or the defense in that case continues to assert the defense that to the extent an uninjured class member is in the four corners of the class definition – that's a reason why the class can't be certified. But separate and apart from that, obviously, when cases get certified, settlements typically follow. How did the plaintiffs' bar do on the settlement front in the securities fraud class action space?

Nelson: The plaintiffs' class action bar successfully converted class certification rulings into class-wide settlements at a brisk pace in securities fraud litigation. The top 10 securities fraud class action settlements totaled $2.65 billion in the past year. By comparison, the top 10 securities fraud class action settlements totaled $5.4 billion in 2023.

Jerry: Well, that's certainly a drop, but it's still an incredible amount of money that was collected by the plaintiffs' securities fraud class action bar. So, it will be interesting to see if 2025 replicates that sort of success that the plaintiffs enjoyed in 2024. Well, great analysis, Nelson, and thanks so much for joining this week's Class Action Weekly Wire.

Nelson: Thank you.

Disclaimer: This Alert has been prepared and published for informational purposes only and is not offered, nor should be construed, as legal advice. For more information, please see the firm's full disclaimer.