- within Cannabis & Hemp, Law Practice Management and Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

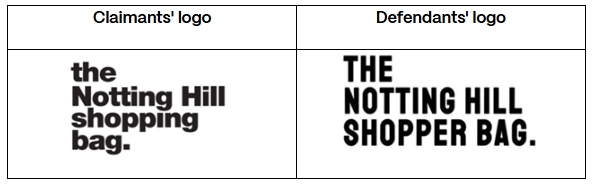

The recent decision in Courtnay-Smith & Anor v The Notting Hill Shopping Bag Company Ltd & Ors [2025] EWHC 1793 (IPEC) offers a cautionary tale for businesses and their advisors about the importance of safeguarding a company's IP while a company is restructured or goes into administration. Set against the bustling backdrop of Portobello Road Market, the dispute arose between two groups of traders over the rights to the 'THE NOTTING HILL SHOPPING BAG' brand and logo, both used on tote bags sold in Notting Hill since 2009. The judgment of Deputy High Court Judge Master Kaye considered issues of trade mark infringement, copyright infringement and passing off.

Background

Natasha Courtenay-Smith, the First Claimant, was the original creator of the brand THE NOTTING HILL SHOPPING BAG and operated her business through a company known as The Notting Hill Shopping Bag Company Limited (the 'Dissolved Company'), of which she was the director and shareholder. Ms Courtenay-Smith designed the logo for her brand in around 2008-2009 and registered a figurative mark in 2013. The history of the Dissolved Company is fairly convoluted so to distil the key events: in 2018, the Ms Courtenay-Smith voluntarily dissolved her company without transferring the trade mark or associated goodwill. Consequently, these assets vested in the Crown as bona vacantia (ownerless property that passes to the Crown).

In around 2023, Ms Courtnay-Smith discovered that two brothers were operating under similarly named companies, The Notting Hill Shopping Bag Company Limited, (First Defendant), and The Notting Hill Shopper Bag Ltd, (Third Defendant). The Defendants were marketing their own 'Notting Hill Shopper Bag' products and had applied to register figurative marks for THE NOTTING HILL SHOPPING BAG and THE NOTTING HILL SHOPPING BAG. In response, she restored the Dissolved Company to the register and purported to assign the trade mark to a newly incorporated entity, The Notting Hill Bag Company Limited (NHBCL) (Second Claimant), which subsequently applied to renew the trade mark. The Claimants then issued proceedings; NHBCL for trade mark infringement and passing off and Ms Courtnay-Smith for copyright infringement. All three pending trade mark applications in the case were, at the time of trial, subject to pending opposition actions at the UKIPO.

Decision and Analysis

The IPEC dismissed all claims, providing a detailed and at times unforgiving analysis of the legal consequences of corporate dissolution for IP rights. The Deputy Judge was critical of the reliability of certain evidence, noting that key financial figures and details of product names were provided in the UKIPO proceedings but not in the IPEC claim. There was a marked lack of contemporaneous documentation from both sides, and the court found the Defendants' evidence on trading history and product development to be evasive and, at times, not credible. The Claimants' evidence was more consistent but still suffered from gaps, particularly in relation to sales and the transition of the business.

The judgment is notable for its guidance on the restoration and vesting of assets following dissolution, a process that rarely comes before the court. When a company is dissolved, its assets (including trade marks and goodwill) vest in the Crown as bona vacantia. Restoration of the company under the Companies Act 2006 can, in some circumstances, revest assets in the company, but this is subject to strict statutory time limits and does not revive rights that have expired in the interim.

Trade mark infringement

The Second Claimant claimed trade mark infringement pursuant to section 10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 ('TMA 1994'), relying on the registration of the figurative mark for THE NOTTING HILL SHOPPING BAG.

Kaye DJ found that the Claimants' trade mark had expired on 2 May 2023 and was not validly renewed. At the time of the attempted renewal on 22 March 2023, the mark was vested in the Crown as bona vacantia, meaning the Crown can generally disclaim or sell the relevant property, including intellectual property rights. As such, neither the Claimants nor the Dissolved Company had authority to renew the mark. The Crown, as a matter of policy, does not renew trade marks or authorise others to do so and once vested in the Crown, only it can give permission for any continued use of the applicable logo, brand name or trade mark that had vested in the Dissolved Company. The subsequent assignments of the trade mark, after the Dissolved Company was restored, were ineffective because there was no longer a valid trade mark to assign. Therefore, NHBCL never became the proprietor of the trade mark, and the renewed mark was a nullity.

This presented a fundamental problem for the Claimants in pursuing its action for trade mark infringement.

Goodwill and Passing Off

For a successful claim in passing off a claimant must establish that it has protectable goodwill in the UK, a defendant has committed an actionable misrepresentation that has caused damage to the claimant's goodwill - the 'classic trinity', as set out in Reckitt & Coleman Products Ltd v Borden Inc (the "Jif Lemon" case).

The judgment is particularly instructive on the fate of goodwill following dissolution. Kaye DJ held that any goodwill attached to the business was destroyed upon dissolution. This was not merely a cessation of trading, but a deliberate and final act of abandonment. Restoration of the Dissolved Company did not revive the lost goodwill and attempts to assign goodwill in gross (i.e. without the underlying business) were ineffective.

Kaye DJ found that NHBCL's claim to have generated its own goodwill in the intervening years also failed on the evidence. There was insufficient proof of trading activity, reputation or sales of the relevant branded bags during the period between dissolution and the alleged acts of passing off (around November 2022). The court scrutinised NHBCL's social media presence and marketing activity, finding them inadequate to support a claim to goodwill. NHBCL's social media following was minimal, with only 923 Instagram followers and 216 Facebook followers at the time of issuing the claim. There was no evidence as to when or where these followers were acquired, nor any indication that they represented a customer base in the UK during the relevant period.

The limited number of invoices to wholesalers or stockists that were produced by NHBCL did not specify whether the bags supplied were those bearing the disputed logo and brand name. Furthermore, sales to Organic Hill, the main wholesaler, could not be relied upon to establish NHBCL's goodwill, as Organic Hill continued to generate its own goodwill independently. The court was clear that the mere use of a logo or brand name is not enough to establish goodwill; there must be an evidential base, such as sales, marketing, or public recognition, and this was lacking.

Copyright infringement

Ms Courtenay-Smith claimed copyright infringement pursuant to section 16(2) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ('CDPA 1988'). The court accepted that the logo was an original artistic work within the meaning of the CDPA and that Ms Courtenay-Smith owned the copyright. However, it found that the level of creativity involved was low. The court's analysis centred on the creative decisions made in designing the logo, such as the use of a lower-case "t", a full stop, left alignment, and the choice of font (Arial). While these were acknowledged as creative choices, the court concluded that the overall degree of creativity was low, given the constraints of the subject matter and the limited scope for originality in a simple, text-based logo.

As a result, the scope of copyright protection was narrow, meaning that only a close copy would infringe. The Defendants' signs, though similar in concept, differed in key aspects. They used all capital letters, a different font, and a different layout (three lines instead of four), and 'SHOPPER' instead of 'SHOPPING'. Kaye DJ held that these differences were sufficient that the Defendants had not copied a substantial part of the copyright work, and there was no actionable copyright infringement.

Comment

This case is a clear warning to businesses and advisers about the serious consequences of corporate dissolution for intellectual property rights. When a company is dissolved, its assets, including trade marks and goodwill, automatically pass to the Crown under the doctrine of bona vacantia. Restoring the company does not guarantee recovery of those rights, especially if statutory renewal deadlines have been missed.

The court's approach to goodwill can be equally uncompromising, confirming that goodwill is destroyed by deliberate abandonment and cannot be revived by subsequent restoration. The case also illustrates the risks of overlooking the legal status of IP assets during corporate events like dissolution, which can have irreversible consequences for enforcement and commercial value.

Finally, the case highlights the narrow copyright protection available for simple, text-based logos. While copyright may subsist, infringement is unlikely unless the copying is very close.

Key Takeaways

- Corporate dissolution can permanently extinguish trade marks and goodwill if not properly managed.

- Restoration of a company does not automatically revive expired IP rights or lost goodwill.

- Goodwill must be transferred with the business, not in isolation.

- Assignments of IP after dissolution are ineffective if the rights have lapsed or vested in the Crown.

- Copyright protection for simple logos is real but very limited in scope; only close copies are likely to infringe.

- Complex, fact-intensive disputes may not be well-suited to the IPEC's time and cost limitations, potentially leaving key issues unresolved.

"To revest company assets which have passed bona vacantia to the Crown there are two broad options: restore the company or apply to vest the assets. Both require a court order. The alternative is to buy the assets from the Crown"

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.