- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

Formula 1 (F1) is the highest class of single-seater automobile racing sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The 'formula', or set of rules, includes cars with 'open' cockpits, augmented by a 'Halo' introduced to improve driver safety, open wheels, which can cause nightmares for aerodynamicists, and 1.6 litre V6 turbo-charged engines with Energy Recovery Systems, which are relevant to current road cars.

Competition and innovation

The racing series is extremely competitive with some of the best engineers and drivers battling it out to win the championship. Margins in the world of F1 are measured in thousands of a second, millimetres, and grams. Therefore, any advantage that can be gained can have a dramatic effect on a turn, a race, or a championship.

As a result, teams of engineers work around the clock to maximise performance by optimising individual elements on the car and by exploiting any loophole in the regulations to invent new solutions to give their team and driver the edge.

Yet, there does not appear to be a public patent war going on

alongside the F1 circus as it moves around the world. It may be

surprising to some to find out that Ferrari and Mercedes F1 teams

are not locked in a perpetual patent war in a bid for supremacy

over the automobile racing world.

On the face of it, F1 appears to be exactly the type of environment

that would be a breeding ground for new ideas and patentable

inventions. It has cutting edge technology, monetary resources in

the hundreds of millions, and some of the brightest minds in the

world.

So, why are there no Apple v Samsung, or Motorola v Microsoft style patent litigation suits? Does this mean that F1 is not a driving force behind Intellectual Property and innovation?

As one can imagine, the answer is a complex one with many reasons why F1 teams do not appear to be locked in litigation battles or even constantly filing patent applications for new inventions which make the F1 cars go faster. However, just because we are not aware of patent filings which result from the innovation of F1 engineers, it does not mean that the patents to do exist or have not had an impact on our day to day lives.

Regulations

The most common reason given for a lack of patents in F1 is based on a blog by James Allen, an F1 correspondent, who quoted a "Senior F1 Engineer". It is said that the reason given is "...because if a team takes out a patent on a design, that then locks in an advantage the other teams cannot access. Therefore the other teams will simply vote it out through the FIA Technical Working Group process by the end of the season in question".

Essentially, the world of F1 wants as many cars competing for the win as possible to keep the sport entertaining. Therefore, there are regulations in place to keep the playing field level. These regulations mean that if an F1 team were to try and enforce a patent, the patented technology would be ruled illegal by the FIA, and then even the patent holder would not be able to use their patented technology in a race.

So, one of the main factors for the lack of patent disputes in the world of F1 is not that the teams are being overly sporting and allowing each other to use their latest technology. On the contrary, the lack of patent disputes is down to the fact that the teams in the sport are not able to benefit from a patent in the same manner that their parent companies would outside of the sport in the real world. Therefore, based on the above, it does not seem like there is much point in an F1 team obtaining a patent to protect its inventions.

Time sensitivity

Even though the FIA's regulations provide a get out of jail card for F1 teams who may face patent infringement proceedings, the regulations are not the only issue with the patent system in the fast-moving industry of F1.

Another problem facing F1 teams and their intellectual property is the time period involved in obtaining an enforceable patent.

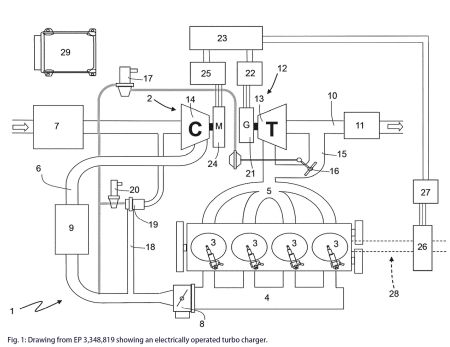

Consider, for example, Ferrari invents an electrically-operated

turbocharger in which the turbine and the compressor are not

mechanically linked by a shaft, as shown in Fig. 1.

Now imagine that this new turbocharger is legal in terms of the

formula and allows the Ferrari engine to produce more power worth a

tenth of a second per lap whilst improving component reliability.

Clearly, such an invention would give Ferrari an advantage over the

field which would be copied by rivals.

In order to maintain their advantage at every race of the season, Ferrari would need to obtain a granted patent in at least each territory which hosts an F1 race. Just some of the territories include, for example, Australia, Brazil, China, France, Mexico, the UK, and the US.

The patent applications could be filed individually in each country or, perhaps more conveniently, centrally using the PCT. However, Article 21 (2)(a) PCT states that "the international publication of the international application shall be effected promptly after the expiration of 18 months from the priority date of that application". Similar clauses can be found in the legislation of other jurisdictions, for example Article 93 (1)(a) of the European Patent Convention.

Therefore, publication of the patent application will usually occur after the season has finished, as can be seen from the example timeline in Fig. 2. As a result, Ferrari would have no patent rights to enforce and not even any provisional protection for a season and a half. Ferrari would have to request early publication in each territory or under the PCT to bring publication forwards. In any case, full patent rights in one territory would not be obtained until grant of the application in that territory. In any case, it could take Ferrari 2 years or more to obtain all the protection they need.

In the time taken to obtain the patents, the F1 world will likely have moved. This could be due to an invention by another team that means the Ferrari turbocharger is no longer the advantageous solution it was two years ago. Alternatively, this could be due to a rule change which effectively outlaws the electrically operated turbo-charger. In either case, the patent may not be of any use to the F1 team itself.

Patentability and disclosure

A further reason that there appears to be a lack of patent activity within F1 is that some of the inventions are not patentable. Take, for example, a front wing of an F1 car. Some consider them engineering masterpieces – others monstrosities. However you view the front wing, a lot of time and detail goes into perfecting it. So much so, that some teams update this part of the car every few races: an occurrence which is more likely this year given the latest raft of aero changes to the formula and the different concepts opted for by the teams.

However, although the front wing is updated frequently, the update is normally just an iteration, or optimisation, of the previous wing – possibly a change of angle of an endplate or a widening of a flap slot gap. Such iterations are unlikely to get over the inventive step hurdle.

Often aerodynamic changes need to be tested in the real world to make sure that the airflow is behaving as it should or as it did in the wind tunnel tests or as determined using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software. And given F1's lack of behind closed doors testing, any new component bolted onto a car is likely to be snapped by photographers and discussed by bloggers from around the world. This instant disclosure, especially of visible components, means that if a team were to obtain a patent, they may have to file an application before the effectiveness of the component has been verified in the real world. This is not a risk many businesses are likely to take and so we probably should not expect any different from the F1 teams.

An invention like the "new" turbocharger mentioned above may possess novelty and the inventive step required to obtain a patent. Nevertheless, the team has to balance the commercial value that the patent may bring – it is unlikely that family road cars will require an F1 front wing – against disclosing to competitors exactly how the invention works.

In order to obtain a granted patent the application must provide an enabling disclosure. This means a person skilled in the art must be able to work the invention i.e make and use from the teaching of the application. In the F1 environment, where the slightest advantage over a rival can win you a race, and where a patented invention can be ruled illegal to maintain a level playing field, competitors do not want to help each other by publicly disclosing their inventions if they can help it, as the disclosure can be advanced upon by competitors and especially because there is no guarantee of grant. Therefore, the enablement requirement of a patent can deter a team from filing an application.

Consequently, the combination of the FIA's regulations, and the issues surrounding time sensitivity, patentability, and disclosure means that the teams must find a different way to enjoy the advantage of their invention whilst preventing their competitors from using it, or even knowing about it.

Trade secrets

The way in which F1 teams generally choose to protect their inventions is through trade secrets. Article 39 of the TRIPS Agreement defines a trade secret as information which is not generally known or accessible to persons within circles who normally deal with that kind of information, which has commercial value because it is secret, and which has been subject to reasonable steps to keep it secret.

In this way, the teams do not have to disclose any information

about the innovations, especially ones that are hidden away under

the body work. The teams go to great lengths to keep their

information secret, from using screens and covers at the race track

to hide the physical car, to team issued encrypted USB devices to

prevent digital data and designs being leaked. Therefore, unless

there is a breach of confidence or some unfortunate accident which

exposes the inner workings of a car, the teams are able to keep

inventions under wraps.

The pitfall with trade secrets, is that, well, people tell secrets

and F1 has been no stranger to spying scandals. There was

"Spygate" back in 2007 which involved McLaren, Ferrari,

and Renault. Even more recently, one team accused an employee of

taking technical files with him before his move to a rival team,

which in the end did not materialise.

It is known that engineers do often move between the teams, albeit after a long gardening leave period, and so a transfer of ideas, or at least philosophies, is likely to be a common theme even if specific technical data is not taken.

Hidden patent applications

Just because trade secrets form a large part of the way F1 teams protect their Intellectual Property does not mean that they do no file patent applications to protect their innovations.

Particularly, the filing of patent applications by F1 teams takes place on inventions which they believe will be commercially successful. This is especially true for technology that can be adapted or filtered down into high performance road cars and now it is becoming more common in road cars. In some cases, the technology patented by F1 teams is often a known technology which has had limited success but is then repurposed or "perfected" and at this stage it can then be fed back into our day to day lives.

However, for a number of reasons including complex company structures and collaborations between F1 teams and other companies, the patents themselves can sometimes be tricky to find. As patenting an invention leads to the opening up of knowledge to competitors, the teams try to hide the applications by using unusual titles or applying for the patent using the parent company's name so that the invention 'hides in plain sight' or by using an associated subsidiary, etc., to hide the application.

For example, searching Scuderia Ferrari, the F1 team, in a patent database will return no results but searching Ferrari SPA will return over 1,000. Similarly, Williams F1 team will often file under Williams Advanced Engineering, and McLaren F1 under McLaren Automotive Group. This can make sorting inventions made by the larger company and inventions derived from F1 teams difficult to differentiate. Furthermore, teams like McLaren have companies, such as McLaren Applied Technologies, through which technology perfected in F1 is repurposed or applied to provide solutions for problems in sectors other than racing and in some cases even outside the automotive sector.

F1 patents

F1 has given us carbon fibre monocoques, "flappy paddle" semi-automatic transmissions, sequential transmissions, improved control electronics for anti-lock brakes, traction control, and engine management, as well as improvements in fuel efficiency, aerodynamics, and energy recovery systems.

Although patent applications for inventions from F1 can be difficult to find and identify, there are some applications which are regarded at F1 technology which either has or will filter down into road cars.

One of these examples is EP 1,402,327 B2. The patent relates to a mechanical device known as an inerter, a third element in a suspension system alongside the springs and shock absorbers, as shown in Fig. 3. For years, the device was kept secret using a non-disclosure agreement between Cambridge Enterprise and McLaren, who referred to using the codename "J-damper".

The inerter works by being attached at one end to the car body and at the other end to the wheel assembly. A plunger slides in and out of the main body of the inerter as the car moves up and down which causes the rotation of a flywheel inside the device in proportion to the relative displacement between attachment points.

It was first run on the McLaren car in 2005 and offered improved mechanical grip and handling. It is now supplied by Penske to each F1 team.

The inventor, Professor Smith, had previously worked with Williams F1 on its active suspension system, which was so advantageous that active systems were banned from F1. It is clear that Smith's involvement in F1 helped to identify the problem he has solved with his inerter, especially with the banning of the active systems.

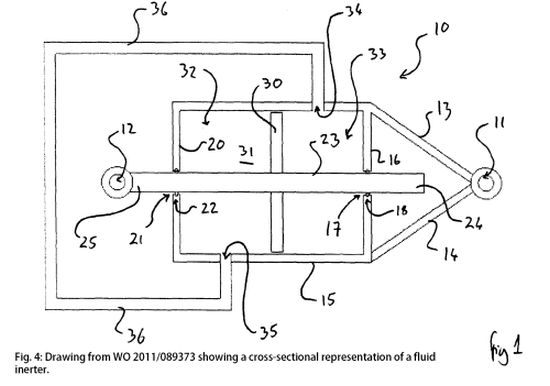

Since Professor Smith's inerter, F1 has made some developments of its own. Lotus Renault GP, the team that existed before the current Renault F1 team, filed an application, WO 2011/089373, directed towards a fluid inerter comprising piston acting on a fluid in a feed line between opposing sides of the piston. In this invention the inertial reaction is provided solely by the fluid such that a flywheel arrangement is no longer needed.

Another of the well-known F1 patents is a KERS patent, GB 2,469,657 (B) or EP 2,422,110 (B1), titled "Flywheel Assembly". It was filed by Williams Hybrid Power Ltd, which was a division of the company which owned Williams F1. This is one of the earlier patents relating to the Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems, and was part of a large patent portfolio. The portfolio was sold in 2014 to GKN with a view to developing the technology for public transport. Variations and developments of such KERS systems can be found on performance sports cars.

In addition, the current V6 hybrid turbo engine formula has made large strides in Energy Recovery System performance, using kinetic and heat energy, to the point that Mercedes claims to have broken the 50% thermal efficiency mark. The engine formula was chosen for just this reason – to be relevant to road cars so that developments will find their way onto road cars. Perhaps we will see technology patented by Mercedes on their road cars soon – maybe patented split turbocharger technology: an idea taken from Daimler's truck division?

F1 collaborators

It is not only the teams that compete in F1 which have inventions to protect using patents. Each F1 team works closely with a number of partners or sponsors towards achieving the goal of winning. This can be through technical partnerships, for example, between Mercedes and Petronas in developing fuels for more efficient combustion or improved lubricants. One example from the Mercedes-Petronas partnership is an oil, Petronas Syntium, which becomes denser as it heats up, supposedly "defying the laws of physics".

Mercedes, together with Daimler, have also produced an innovative NANOSLIDE® coating for engines which is protected by over 40 patents. The extremely thin, low-friction coating reduces friction between cylinders and the engine block which saves fuel.

Another of Mercedes' partners Epson holds over 50,000 patents worldwide and files around 4,000 new patent applications a year. Mercedes uses products containing these patented products and methods to help in the design and build of a championship winning car.

Brembo, the brake disc manufacturer, has over 400 patent families based around new materials and component design, many of which result from meeting the deceleration and temperature requirements of F1 cars.

It is not just automotive engineering collaborations which yield inventions in F1. Partnerships between F1 teams and clothing or fitness equipment companies also produces patentable inventions. For example, Williams' partnership with Cybex, a fitness equipment manufacture with over 90 patents, provides the drivers with some of the best equipment to physically prepare their bodies for a race.

Renault also previously partnered with Athletic Propulsion Labs, an athletic footwear and apparel company. APL developed shoes at the front of footwear technology for the team to wear. You may think shoes have nothing to do with F1, but a mechanic who works around the clock would be glad to have lightweight, luxury shoe protecting their feet. APL's Load N' Launch® technology helps increase vertical leap, which may be of particular use to a front jack man facing an F1 car that has overshot its marks!

Even Pirelli, the sole tyre supplier for F1 since 2011, has a back catalogue of patents which has no doubt been bolstered by the innovations and expertise gained from having to produce compounds which are capable of withstanding the conditions forced upon them by an F1 race.

Technology trickle down

As you probably know, all these technologies are starting to make their way onto road cars. Hybrid cars can be found everywhere, their energy recovery systems benefitting from the knowledge and research of F1. Even, carbon-ceramic brake disks are making it onto sports cars.

As the hybrid turbo era of engines continues, the progress made by F1 teams is of particular importance to today's road cars. So, we can expect the time from F1 conception to inclusion in the everyday road car to shorten.

In conclusion, it is clear that F1 is a driving force behind innovation in the automotive sector, and outside of it. However, due to the use of trade secrets to protect most inventions, and how difficult it is to determine whether a patent application is derived from F1 innovation, the exact size of that force is difficult to quantify from a look at the patent register.

Formula E

One area of motorsport racing in which patent filings does show how motorsport drives innovation is Formula E. In the last few years, advances in electric vehicle technology has led to a new "Gen-2" car. The advances in the technology associated with Formula E is backed up by the number of patent filings by the teams participating in the thousands.

This is perhaps a topic to be discussed in more detail in a later issue.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.