- within Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Property and Retail & Leisure industries

Since Theresa May's 2017 White Paper: Fixing our Broken Housing Market stated that renters needed a fairer deal, the residential real estate sector in England has braced itself for change. The following year, the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018 was passed in order to make sure that rental homes in England are safe, healthy and free from things that could cause serious harm. In the next year, the Tenant Fees Act 2019 banned most letting fees and capped tenancy deposits paid by tenants in the private rented sector.

The previous Government then started work on the Renters' Reform Bill which was much-discussed (including here) but not implemented before the handover to the current administration.

The Renters' Rights Act 2025, which gained Royal Assent today, took that abandoned Bill as its starting-point, but contains certain key differences. Whilst there is general relief that the new regime can now be quantified and understood, some aspects of the Renters' Rights Act 2025 will negatively impact on residential landlords.

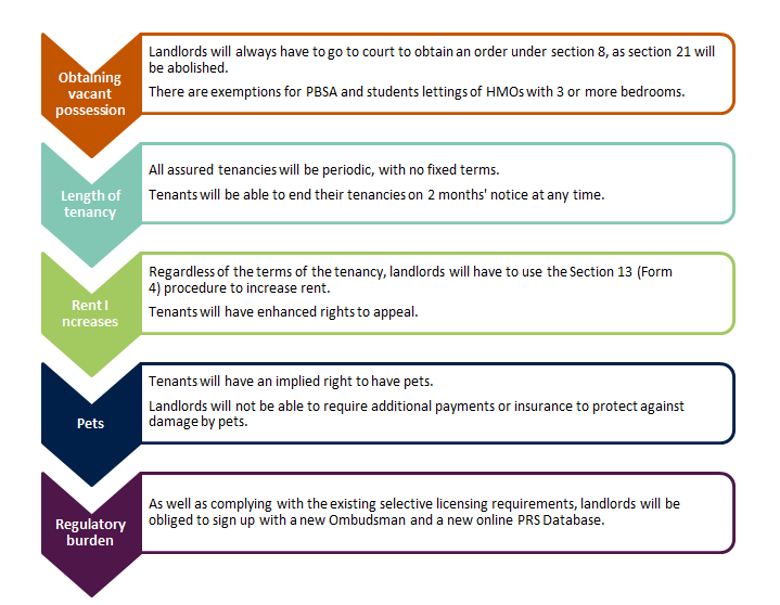

1 In summary, what key changes will the new Act introduce?

2 In more detail, what does the new Act say and what might it mean for landlords and agents in practice?

2.1 Replacement of ASTs by periodic tenancies

Assured shorthold tenancies will be abolished and henceforth all new and existing PRS tenancies that are assured tenancies will be or become assured periodic tenancies. Tenancies that are not assured tenancies will not be affected – this includes holiday lets and tenancies with low rents.

Although tenants cannot be required to leave a property without the landlord going through a court process, a tenant can serve notice to terminate on two months' notice at any time, to expire at the end of a rent payment period. This may cause several problems for landlords:

2.1.1 It may make it hard for landlords to calculate their financial positions because they will not know how long a tenant intends to be in occupation, or how long it will take for them to re-let their units between tenancies.

2.1.2 More, shorter tenancies will increase landlord costs because, under the Tenant Fees Act 2019, the costs of the re-letting process fall on the landlord.

2.1.3 It is also open to abuse by tenants who are looking for short-term occupation but do not want to pay the higher rents that such occupation agreements usually demand. A tenant could in theory enter into a rental agreement saying they intend to occupy as their permanent home but then serve two months' notice on the first day of their term.

Qualifying PBSA (note that some aspects of the definition of this asset class still remain subject to secondary legislation) will be exempt from this part of the new regime. Landlords of other types of student accommodation, such as qualifying HMOs with 3 bedrooms or more, will also be able to secure possession of their properties in time for the new academic year by serving the relevant statutory notice on tenants before the tenancy starts.

2.2 Abolition of the section 21 process for obtaining possession

Under the new regime, the only way that a landlord will be able to obtain vacant possession of a rented property is to use the section 8 procedure. This will require the landlord to establish the existence of one of the statutory grounds for forfeiture (see paragraph 2.3 below) and to use the court process if the tenants refuse to leave upon expiry of such a notice. There is therefore significant concern that landlords will face long and costly delays in gaining possession, and that the current court backlogs will increase to unworkable levels.

2.3 Adjustments to the section 8 procedure

Under the new regime, the section 8 possession process must be followed as the only way for a landlord to regain possession. This requires the landlord to establish the existence of one of the specified statutory grounds. Although the statutory grounds for possession have been somewhat widened (as set out below), the threshold to satisfy the grounds have in some cases been increased.

For mandatory grounds, the court must award possession if the ground is proven, whereas for discretionary grounds, the court can consider whether or not eviction is reasonable even when the ground is met. Where a tenant is at fault, landlords can give notice using the relevant grounds at any point in the tenancy. This includes where a tenant commits antisocial behaviour, is damaging the property, or falls into significant arrears.

The Government has amended the section 8 grounds to protect tenants who temporarily fall into rent arrears, by increasing the mandatory threshold for eviction from two to three months' arrears (or to least thirteen weeks' rent arrears if rent is payable weekly or fortnightly), and has increased the notice period from two weeks to four. In addition, if the tenant is entitled to Universal Credit, any amount that was unpaid only because the tenant had not yet received the payment is to be ignored when calculating any arrears being relied upon.

Landlords will be able to regain possession if they decide to sell or move in, subject to a twelve-month protected period at the beginning of a tenancy, on giving four months' notice to the tenant. However, they would then be debarred from letting the property for the following twelve months, to ensure that this provision is not abused. This may prove punitive if the landlord's intended sale does not proceed (in the context of a current residential market where around one in three transactions fail such that the Government proposes various reforms to the system) as the landlord would be unable to fall back on letting the property during this time.

The section 8 procedure will not be available until the landlord has properly protected the tenant's deposit or registered their property on the new private rented sector database (see paragraph 2.7 below).

|

Mandatory grounds for possession |

||

|

These grounds require the court to issue a possession order if proven. |

||

|

Ground |

Description |

Notice period |

|

Ground 1 |

A landlord who previously occupied the property as their main home, or who requires it as their or their spouse/civil partner/ defined family member's main home, seeks possession. The tenant must have been notified of this possibility before the tenancy began. The current tenancy began at least 1 year before the relevant date. NB The landlord cannot re-let it for 12 months after the tenants move out. |

4 months |

|

Ground 1A |

The landlord intends to sell a freehold or assign/ grant a leasehold interest in the property. The current tenancy began at least 1 year before the relevant date. |

4 months |

|

Ground 1B |

The landlord is a private registered provider of social housing and intends to sell a freehold or grant/ assign a leasehold interest in the property, and the assured tenancy was entered into pursuant to a rent-to-buy agreement. |

4 months |

|

Ground 2 |

The property is subject to a mortgage or charge that began before the tenancy, and the lender requires vacant possession to exercise a power of sale. |

4 months |

|

Grounds 2ZA- D |

The landlord who is seeking possession holds its interest in the property under a lease which will end or expire 12 months after the relevant date. |

2 months |

|

Ground 3 |

The tenancy was a fixed term of no more than eight months and was previously used as a holiday let. |

|

|

Ground 4 |

The tenancy was a fixed term of no more than 12 months and was used as student accommodation during the previous 12 months. Can only be used by specified educational establishments. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 4A |

The tenancy is student accommodation, and the landlord gave the tenant notice before the tenancy started that possession will be required between 1 June and 30 September in order to re-let to students. Can only be used for HMOs of 3 or more bedrooms, let to full-time students. |

4 months |

|

Ground 5 |

The property is held for a minister of religion to perform their duties and is now required for that use. |

2 months |

|

Ground 5A- 5H |

Various employment-related reasons, or supported housing tenancy-specific reasons. |

2 months or 4 weeks, depending on the ground |

|

Ground 6 |

The landlord plans to demolish or redevelop the property and must be able to demonstrate that it cannot reasonably do the work with the tenant in residence, and the tenancy began at least 6 months beforehand. |

4 months |

|

Ground 6A |

The landlord seeking possession is a social landlord, and the property was let to the tenant to facilitate redevelopment of another dwelling. |

4 months |

|

Ground 6B |

Continuing the tenancy would put the landlord in breach of one of the specified statutory provisions. |

4 months |

|

Ground 7 |

The tenancy has passed to someone by will or inheritance, and the landlord begins possession proceedings within 24 12 months of the former tenant's death. |

2 months |

|

Ground 7A |

The tenant, or anyone living in or visiting the property, has engaged in serious antisocial behaviour, as evidenced by a conviction, noise abatement order, or other relevant finding. |

2 months |

|

Ground 7B |

The tenant does not have a "right to rent" in the UK and has been notified of this by the Home Office. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 8 |

Serious rent arrears exist both when the Section 8 notice is served and at the court hearing. This threshold is eight thirteen weeks for weekly/fortnightly rent, or two three months for monthly rent. Any sums that are due to the tenant by way of unpaid Universal Credit cannot be taken into account. |

4 weeks |

|

Discretionary grounds for possession |

||

|

For these grounds, the court will decide whether to grant a possession order, considering if it is reasonable to do so. |

||

|

Ground |

Description |

|

|

Ground 9 |

The landlord offers suitable alternative accommodation to the tenant. |

2 months |

|

Ground 10 |

The tenant is in some rent arrears at the time of serving the notice and starting proceedings, but not at the level required for mandatory Ground 8. |

4 weeks |

|

Ground 11 |

The tenant has persistently delayed paying rent, regardless of the level of arrears. |

4 weeks |

|

Ground 12 |

The tenant has breached one or more obligations of the tenancy agreement (other than payment of rent). |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 13 |

The condition of the property or common parts has deteriorated due to the tenant's neglect or actions. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 14 |

The tenant has been a nuisance or annoyance to neighbours, or used the property for immoral or illegal purposes. Proceedings for this ground can be started immediately. |

2 weeks Immediate |

|

Ground 14A |

A social landlord can evict a perpetrator of domestic violence if the victim has permanently left the property. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 14ZA |

The tenant or an adult resident has been convicted of an indictable offense during a riot. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 15 |

The condition of the landlord's furniture has deteriorated due to the tenant's ill-treatment. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 16 |

The tenant's right to occupy the property arose from their employment by the landlord, and that employment has now ended. |

|

|

Ground 17 |

The landlord granted the tenancy based on a false statement made by the tenant. |

2 weeks |

|

Ground 18 |

The tenancy is of supported accommodation, and the tenant has unreasonably refused to co-operate with the person providing support services. |

4 weeks |

2.4 Rent increases

Landlords will continue to be able to increase rents once per year to the market rate by serving a 'section 13' notice, setting out the new rent and giving at least 2 months' notice of it taking effect. However, this process will be altered as follows:

2.4.1 As before, if a tenant thinks the proposed rent increase is higher than the market rate, they can challenge the figure at the First-tier Tribunal, which will determine what the market rent should be. Previously, tenants faced the risk that the Tribunal may decide that the market rent was higher than the landlord's proposal – this is no longer the case, so that instead the landlord's proposal is treated as an upper limit.

2.4.2 Also, the new rent will be payable from the date of the Tribunal determination, not from the date of the landlord's notice, so that the landlord has to bear the cost of the delays in getting to the Tribunal's decisions. The Tribunal can still defer rent increases by up to a further 2 months where it deems this necessary in order to save the tenant from undue hardship, under s.14(7) HA 1988.

2.4.3 Other forms of rent increase, such as rent review clauses, will be prohibited.

It has been suggested that, as there is now no downside for a tenant in challenging a section 13 notice, tenants will routinely do so, and this will not only delay the date on which rental increases take effect but also further clog up the courts.

2.5 Private Rented Sector Landlord Ombudsman

This new service is intended to provide quick and binding resolutions for tenants' complaints about their landlord, and will bring PRS tenant complaint resolution into line with established redress practices for tenants in social housing and consumers of property agent services. It is unfortunate that the ombudsman will not have any jurisdiction to hear landlord complaints as this may have provided a means to settle some forms of tenant breaches and reduce the courts' workloads.

2.6 Private Rented Sector Database

This online portal will "help landlords understand their legal obligations and demonstrate compliance" and will be a way for tenants to see if landlords have been sanctioned and for local authorities to target their enforcement activities. Landlords will need to be registered on the database before marketing the property, and in order to use certain possession grounds.

The database will contain the names of residential landlords, the details of the properties they own that are within the PRS, and details of any banning orders or penalties imposed on them for relevant offences. Landlords will have to register on the database and then keep their details up to date. Enforcement provisions include the service of a rent repayment order.

As with the ombudsman, it is unfortunate that this is a one-sided database which does not protect landlords against tenants who repeatedly cause problems for their landlords. Nonetheless, it means that landlords who offer a good and compliant service will be better able to distinguish themselves from landlords who do not.

The cost of setting this up and maintaining it will fall on landlords. Many of them already pay hefty licence fees to local authorities under selective licensing schemes, so questions have been asked as to whether this duplication is necessary or proportionate. Unfortunately, during the Bill's committee stage, Matthew Pennycook made it clear that the database would operate alongside selective licensing.

2.7 Deposit protection

Under Section 215 of the Housing Act 1996, a landlord cannot serve a Section 21 notice unless the landlord has complied with the deposit protection rules. Under the new regime, a court will not award possession under any ground other than Grounds 7A and 14 (anti-social behaviour) unless the landlord has properly protected the deposit.

2.8 Rent in advance

Landlords and letting agents will not be able to "invite or encourage" or accept payments of rent from the tenant or someone acting on their behalf before the tenancy agreement is signed by both the landlord and the tenant. Any such prepayment would be deemed to be a "prohibited pre-tenancy payment" under the Tenant Fees Act 2019. However, once the agreement is signed, a landlord can ask for and accept a maximum of one calendar month's rent.

2.9 Pets

The Act will give tenants strengthened rights to request a pet in the property, which the landlord must consider and cannot unreasonably refuse. It will not be possible for them to require tenants to pay for pet damage insurance or a higher deposit to cover any additional costs that may be incurred by having a pet on the property, such as damage to flooring or furniture, the need to eliminate fleas from the property, or the need for an intensive clean in case future tenants have allergies to pet fur.

2.10 Decent Homes Standard and Awaab's Law

These standards will be applied to the PRS to ensure that homes are safe. This is currently a problematic aspect of the new regime, as the Decent Homes Standard has historically been applied only to social housing, and the Government has not yet responded to the consultation carried out in 2022 to gather views about how best to apply it to the PRS. It is therefore uncertain what this new requirement would mean in practice.

Awaab's Law will force landlords to fix dangerous homes – from October 2025, social landlords will have to investigate and fix dangerous damp and mould in set time periods and repair all emergency hazards within 24 hours. The full regime will be phased in over a two-year period, so that in 2026 the requirements will be expanded to apply to a wider range of hazards such as excess cold and excess heat; falls; structural collapse; fire, electrical and explosions; and hygiene hazards. Then, in 2027, the regime will expand to the remaining hazards in schedule 1 to the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (England) Regulations 2005. Again, it is unclear yet how this will be applied to the PRS.

2.11 Discrimination

The Act will make it illegal for landlords and agents to discriminate against those prospective tenants who receive benefits or have children. If the property is mortgaged and the terms of the loan contain any restriction on letting to families or people on benefits then these terms will be void, and the same will be true of any similar terms in insurance policies and/or superior leases.

2.12 Rental bidding

Under the new regime, landlords and agents will no longer be able to ask for or accept offers above the advertised rent. Instead, they will be required to publish an asking rent for their property and decline any offers made above this rate. Some commentators have suggested that this will drive up rents, as agents will be incentivised to advertise at the higher end of a spectrum of possible rental figures.

2.13 Strengthened enforcement

Local authority enforcement will be strengthened by expanding civil penalties (including fines of up to £40,000), introducing a package of investigatory powers and bringing in a new requirement for local authorities to report on enforcement activity. Rent repayment orders will be extended to superior landlords, doubling the maximum penalty and ensuring repeat offenders have to repay the maximum amount.

3 Conclusion

The new regime will take effect in stages and will require secondary legislation, but the dates for implementation are not yet known. It is thought that the transition period will be no more than 6 months. The Act will bring about a once-in-a generation shift in the PRS, and the main issues of concern for landlords are likely to be:

- delays in obtaining vacant possession, because the courts will quickly become overwhelmed with the volume of cases;

- difficulties increasing rents because tenants are incentivised to dispute any proposed rental increase;

- increased costs due to the uptick in regulatory requirements, the inability to recover damages caused by pets that (together with other breaches) exceed the standard 5-week deposit, and potentially more void periods because of the inability to agree minimum periods with tenants; and

- greater regulatory risk – it is not yet known or understood how the Ombudsman will operate, what the new database will require from landlords, or how (cash-strapped) local authorities will exercise their new powers.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.