- within Transport, Antitrust/Competition Law and Employment and HR topic(s)

- with Inhouse Counsel

- in Asia

Technological developments are transforming our markets, and the way financial services are provided. Advances in AI, large language models, and other analytics are already creating huge opportunities for firms (and regulators) to enhance services, reduce costs and improve outcomes.

The exponential adoption of AI systems is also changing how decisions are made, dispersing accountability and posing challenges for firms' leadership – in the eyes of consumers and regulators, the firm must be responsible for the AI models they choose to use, and the outcomes. To remain in control of their AI-based systems, designed (and relied on) to perform tasks with increasing autonomy, firms must rely not just on governance and controls, but also reinforce and leverage that uniquely human concept, culture.

Regulators have clearly acknowledged the ongoing need for human expertise and judgements through governance, oversight, monitoring and testing as set out in our previous articles.

How AI use is impacting firms

Delegating more decisions to AI allows firms to optimise efficiency, and it reduces (human) friction. AI systems take decisions based on in-built rules, automated inputs, system generated thresholds and, increasingly, model inference, as the use of predictive AI, generative AI and agentic AI increases.

These AI systems (at least for now) require human involvement in the initial design / set-up phase (with third party implementations, the human involvement may be split across manufacturer / provider and operator).

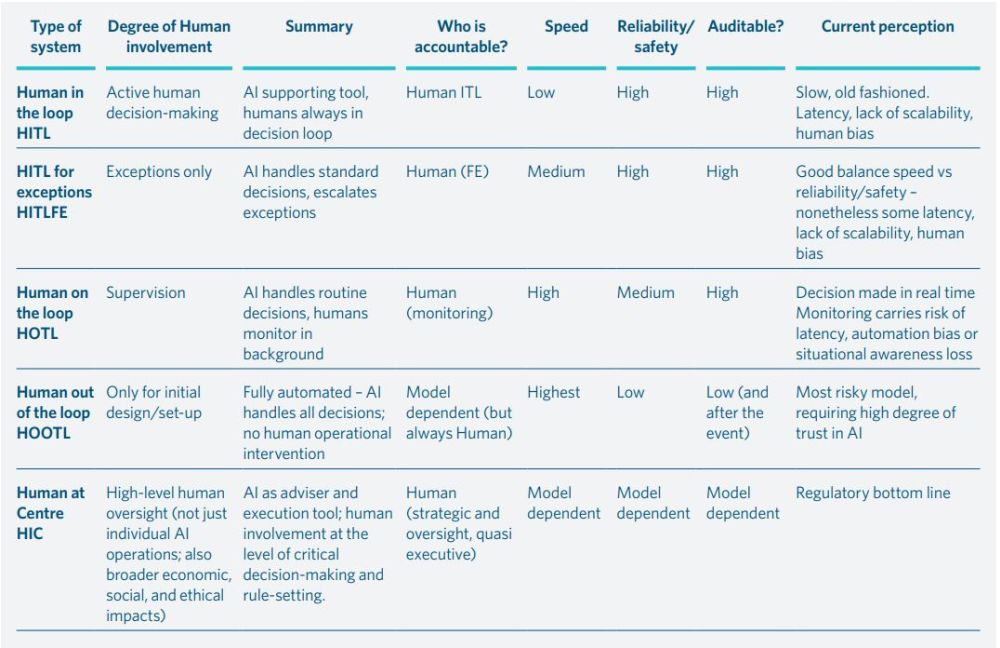

The operation and use of any automated system thereafter involves a trade-off between the speed and efficiency of automation on the one hand, and the safety and reliability of human intervention on the other. The various models for human intervention in AI reflect some of the different trade-offs.

Jon Ford

Partner, London

Breakdown of the ways humans must intervene with AI systems

Although the mere presence of a human in the loop will not be a cure-all for a poorly-designed AI system, some degree of human intervention and judgement is factored into most of the additional safeguards identified by the 2025 IIF-EY annual survey report on AI use in financial services as having been built into AI applications. These include alert systems (log monitoring, upstream downstream monitoring), performance monitoring, backup systems, guard rails / soft blocks, and kill switches / hard blocks.

The sheer complexity and opacity of some AI applications or systems poses particular challenges for monitoring and oversight.

There has been a drop in leadership confidence in preparedness to address technological change in the last six months – some 60% of financial services leaders1 are concerned that over-reliance on AI may impede the development of employee's critical thinking skills and judgement.

Christine Wong

Partner, Sydney

How should firms' governance and cultures respond?

Shifting decision-making to AI brings many benefits, and in the quest for efficiency, firms expect their business and employees to rely on those AI systems.

In practice, however, accountability for the AI systems, and the knowledge and access to data and outputs, is typically dispersed across siloed functions, often divided between technology, operations, compliance, risk and culture, amongst others. While as discussed in 'Diffused accountability – is recalibration overdue?', the division of responsibilities should be clearly set out and understood, the firm also needs to be able to see the whole.

In the past a firm's culture has often acted as an unofficial early warning mechanism to catch what a process or system may have missed – as the New York Federal Reserve's Chief Risk Officer Mihaela Nistor put it, 'a backup system for judgement'.

That mechanism depends on individuals having not only moral courage and critical judgement, but a sense of personal ownership not only in the process, but in business more widely as well. This sense of ownership is a human quality that transcends the regulatory stick of accountability. It is also a quality which is weakened by remoteness from the AI decision-making, the opacity of certain AI systems and the dispersal of responsibilities for the systems and outputs. The prospect of individuals feeling sufficient sense of ownership of a particular AI system, its operation and outputs, to empower them to intervene on the basis that something (that the system was not programmed to identify) doesn't 'feel right' is inevitably diminished.

To support the human intervention that regulators expect, firms need to empower the appropriate individuals not merely to understand how an AI process works, but when it can be trusted, and how to test this, to think beyond the process itself to the way in which it aligns with the AI's purpose, the firm's strategy and the outcomes desired, considering the outcomes actually achieved and any broader economic, societal and ethical impacts – in short, to consider the full picture - an approach which echoes that advocated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority's (FCA's) broader outcomes-focused Consumer Duty.2

Firms need to empower the appropriate individuals not merely to understand the AI process, when it can be trusted, and how to test this, but also to think beyond the process itself to how it aligns with the AI's purpose, the firm's strategy, the desired outcomes and those achieved, and its broader economic, societal and ethical impacts.

Karen Anderson

Consultant, London

Achieving this in turn will require proactive leadership, a culture which supports open dialogue, and cross-functional collaboration that facilitates the sharing of insights and information. Integration and coordination across siloed functions with responsibility for AI systems, and the prompt escalation of signals and management information, will be critical to a firm's successful management of AI-related risks. The importance of creating feedback loops, with the ability to capture not only market signals, market intelligence and internal performance data, but also customer feedback, should not be underestimated.3

Firms will also need to consider whether their organisational functions should be enhanced or redesigned to enable control functions that currently undertake periodic reviews to respond, and adapt, more swiftly and effectively to technologies and business processes that are operating in real time. Again, culture will play an important enabling role.

Ultimately, the reality is that the public, consumers and regulators will hold firms, and the relevant senior managers within them, responsible for the AI models they use and the way in which they operate. A firm's culture will be a critical part of ensuring that the AI models the firm chooses to deploy operate successfully in practice and that any emerging issues are identified before risks crystallise.

Footnotes

1. Russell Reynolds Associates' H1 2025 Global Leadership Monitor, n = 312 Financial Services CEOs, C-level leaders, and next generation leaders

2. Unsurprisingly, the auditing profession has considered these issues in relation to its own role, and the IAASB 2021 FAQs, for example, explore ways for auditors to address automation bias and the risk of overreliance on technology when using automated tools and techniques and when using information produced by the entity's systems.

3. There is increasing reliance on AI tools to automate the collection, analysis, and interpretation of customer data to identify trends, sentiment, and issues in real-time. This can help to identify emerging issues before they escalate, and can facilitate faster improvement in products and services, and in customer experience.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.