- in South America

There are few areas of planning law that can enliven the celebrities and moguls of London in the same way as that of basement development. It is a polarising topic and people are passionate in their views. Queen guitarist Brian May has even gone so far as to describe on his blog his basement-digging neighbours as 'selfish and brutish', referring to the piling rig they were using as an instrument of torture.

There is no denying that basement development has significantly increased in recent years. Karen Buck (MP for Westminster North) introduced the Basement Excavation (Restriction of Permitted Development) Bill 2015-16, a Private Member's Bill, towards the end of last year. At the first reading of the Bill on 16 September 2015, Karen Buck MP said: 'The impact of the size and scale of basement excavations on immediate neighbours is hard to overstate'. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) saw applications rise from 46 in 2001 to 450 in 2013; a 500% increase on 2003 figures. (The Bill has been withdrawn.) Why the recent surge in basement development? Despite popular press suggesting that the increase is due to greedy 'high-net-worth' individuals seeking to enhance their mansion homes with 'private leisure facilities' (swimming pools, tennis courts, garages and/or gymnasiums), in the main, the increase is owing to the rise in house prices.

For those in central London boroughs where space is at a premium and where heritage designations limit the potential for rear or roof extensions, 'subterranean development' (ie new basements and basement conversions) is often seen as a more economical means of increasing space than moving home. Many, particularly those who benefit financially from the construction of basements, suggest it is just a matter of smart maths. In London boroughs where the purchase price is at least £1,000 per sq ft, increasing space through a basement construction at approximately £400-£500 per sq ft is a far more affordable alternative, particularly when you consider the saved costs of not having to move (mortgage, agency and conveyancing fees, stamp duty, etc).

Unfortunately, one person's saving is often achieved at the expense of their neighbours.

Why is there so much resistance to basement development?

Basement development is typically opposed by residents due to the impact this type of development has on quality of life, namely construction noise and disturbance (which may continue for up to three years in extreme cases), but also due to fears over potential physical damage to neighbouring properties. While the majority of planning objections do not relate to the development outcome itself – most completed basements cannot be seen from the outside – there have been some extravagant 'iceberg' proposals that have enraged neighbours and Londoners in general, including:

- the application by Tory donor Edmund Lazarus for a 16,000 sq ft mega-basement that proposed a 25m swimming pool, a cinema, a games room, a cigar room, a two-level gym, a catering kitchen and a yoga studio. Permission was refused;

- the application by John Hunt, the founder of Foxtons estate agents, to carry out work at his Grade II-listed mansion at Kensington Palace Gardens to add five underground levels to the existing three-storey home to create a giant 'museum' for his classic car collection, a swimming pool and full-size tennis court. The sub-fourth and fifth-floor basements were removed from the proposal, but an extension depth of 11m was ultimately approved in 2008 (see Government of the Republic of France v Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea [2015] at para 13); and

- the application by Turner Prize winner Damien Hirst to build a basement at his Grade I-listed home (14 bedrooms over five storeys) to house his personal art collection, which was approved in 2015. Why some basements have been approved while others, often more moderate, have been refused has not always been clear to the public. This article will try to dispel some of the mystery behind the planning considerations for basement development.

Current law on basement Developments

Basement development can require several consents in addition to planning permission, including: building regulation consent; listed building consent; party wall agreement; highway licence; skip licence; parking suspension; street works licence; and freeholder consent. Here we focus solely on planning permissions.

Is planning permission required?

Most basement developments will require planning permission, but not all. There is no provision in the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 (the 2015 Order) which exempts basement development from the need for planning permission; however, basement development is generally considered to benefit from permitted development rights under Part 1, Class A, Sch 2, as it is considered to be works for the 'enlargement, improvement or other alteration of a dwelling house'. These permitted development rights are subject to a number of exclusions set out in paras A.1(a)-(k), and will not apply to flats/maisonettes. In addition, they do not remove the requirement for listed building consent, or the legal requirement to preserve trees located within a conservation area or those subject to a tree preservation order; appropriate consents will still be required.

Until recently there had been some confusion about how to apply the exclusion in para A.1(h) of the 2015 Order to the permitted development rights. The provision in the 2015 Order is effectively no different to the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 1995 (as amended). The wording in para A.1(h) of the 2015 Order states that permitted development rights do not apply in circumstances where:

... the enlarged part of the dwelling house would have more than one storey and –

- extend beyond the rear wall of the original dwelling house by more than three metres, or

- be within seven metres of any boundary of the curtilage of the dwelling house opposite the rear wall of the dwelling house.

The uncertainty related to whether:

- the phrase 'the enlarged part of the dwelling house would have more than one storey' referred to the dwelling house as enlarged by development, ie to include all storeys in the original dwelling house as well as the proposed basement extension, or whether it simply meant the new single-storey basement extension that was being proposed; and

- the seven-metre restriction should be measured from any dwelling house opposite the one being developed, or only the dwelling house that is the subject of the development, ie the application dwelling house.

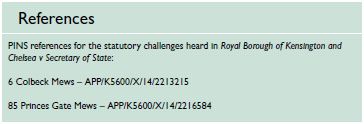

A recent case brought by RBKC, concerning two conjoined statutory challenges over inspectors' appeal decisions to grant lawful development certificates, has provided some clarity on this issue (Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government [2015]; see box on p17 for PINS references). Patterson J, sitting in the Planning Court, determined that:

- the 'enlarged part of the dwelling house' referred only to the development that is being added by way of permitted development rights, not all of the storeys in the dwelling house post-completion of the new (basement) development. The judge went on to say that para A.1(f) (ie: 1(f) under the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Amendment) (No. 2) (England) Order 2008, which applied at the time of the decision and is the same as para A.1(h) under the 2015 Order) deals with enlargements or alterations to the original dwelling house and that each step of incremental development has, therefore, to be judged against that original baseline so that 'piggybacking' or incremental development is caught (see paras 37, 45 and 46); and

- (at para 59) if the 'enlarged part of the dwelling house' was no more than one storey (so para A.1(h) was satisfied), the seven-metre distance was to be measured from the dwelling house that was being extended.

If there is any doubt whether a proposed development can benefit from 'permitted development' rights, an application for a certificate of lawfulness of proposed use or development (under s192(1) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990) can be submitted to the local planning authority (LPA) for a formal decision.

Unless a basement proposal falls within the specific criteria for permitted development, planning permission will be required.

An amendment to the 2015 Order comes into force on 6 April 2016 which clarifies this point; the amendment will now tie the seven-metre restriction to the dwelling house being enlarged (SI 2016/332).

If a planning application is required, how will it be assessed?

Similar to above-ground development, there is a suite of planning policies to be taken into account in the consideration of a proposal involving basement development. These include the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the National Planning Policy Guidance (NPPG), the London Plan, the relevant LPA's development plan and any supplementary planning document (SPD). While the NPPF and NPPG contain nothing specific in relation to basement development, (and the latest consultation

on the government's proposed changes to the NPPF does not indicate that there will be any amendments made to specifically address this issue), their principles regarding design, heritage assets, amenity and sustainable development are all relevant to the assessment of basement development and are typically considered in the development of a LPA's SPD.

While SPDs are not part of the statutory development plan, they set out detailed guidance on the implementation of relevant development plan policies in relation to basement development and are a 'material consideration' for planning officers when it comes to assessing basement applications. In particular, a specific basement SPD will set out the informational requirements for submitting a planning application for basement development (for example, the submission of a construction management plan and structural statement), as well as outline the material considerations that are to be taken into account in designing a basement development, including (non-exhaustive list):

- the design and appearance of the proposal;

- the impact on amenity, such as permanent noise generated by plant and machinery;

- issues regarding trees, landscaping and garden space;

- the impact on traffic, road access, parking and servicing;

- flood risk, ground water, ground conditions and land instability;

- the impact on the significance of a heritage asset;

- sustainable design; and

- the quality of accommodation in the new basement extension.

The table below provides a snapshot of the planning policy progress that has been made by those LPAs most inundated with basement applications.

As is clear from this table, RBKC is the only LPA to have an adopted development plan policy for basement development: Westminster is in the process of doing so (the examination of its basement policy was held from 8-10 March 2016). Even if Westminster's policy is considered sound and ultimately adopted, that does not mean it will not be subjected to the same scrutiny and challenge as RBKC's policy.

In the High Court case of Lisle-Mainwaring v Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea [2015], the claimants, the freehold owner of a house in the borough who wanted to build a basement, and Force Foundations (Basement Force), a specialist in the design and construction of basements, sought to quash RBKC's new development plan policy on basements under s113 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004, contending that RBKC had failed to consider relevant considerations in making the policy. Adopted in January 2015, Policy CL7, the basements planning policy (BPP), imposes strict limits on the depth and lateral extent of basement development, ie it cannot exceed a maximum of 50% of each garden or open part of the site and cannot comprise more than one storey (subject to large-site exceptions).

The claimants challenged the BPP on two grounds:

- (at para 11(i)) that RBKC and the planning inspector (who examined the development plan policy):

-

... failed to take account of a material consideration, namely the permitted development rights for basement development, and the risk of greater reliance on them if the BPP were adopted, without the benefit of any planning control over construction noise and loss of amenity... and

- that RBKC and the planning inspector did not consider and/or assess the 'reasonable alternative' of a 'case-by-case' assessment of basement applications (instead of the application of arbitrary basement limits via the policy), which meant that the LPA had failed to carry out an adequate environmental assessment, as required under Reg 5 of the Environmental Assessment of Plans and Programmes Regulations 2004.

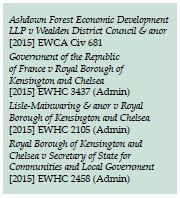

Lang J refused the claimants' challenge on both grounds, confirming that an LPA could adopt a new development plan policy that seeks to restrict and regulate the construction of basements under existing homes, provided that its decision to do so was a reasonable one, reached after taking into account the relevant considerations and adequately explained and justified (at paras 73-74, 123-129 and 141). The judge also reaffirmed that the question of what is a reasonable alternative is a matter of evaluative judgement for the LPA in question, following the Court of Appeal's decision in Ashdown Forest Economic Development LLP v Wealden District Council [2015], handed down the day after arguments in Lisle-Mainwaring concluded.

What is the current position on basement developments?

To summarise:

- A 'single-storey' basement underneath an unlisted

dwelling, which does not include exterior alterations (ie light

wells) or extend beyond the footprint of the existing

dwelling, is likely to constitute permitted development. If so,

it will not require planning permission, thus making it exempt from

the controls that the planning system can offer.

dwelling, is likely to constitute permitted development. If so,

it will not require planning permission, thus making it exempt from

the controls that the planning system can offer.

- An LPA can impose Article 4 directions to remove permitted development rights for basements. If this occurs, a planning application will need to be made and approved before any basement development can be carried out.

- Most LPAs with a basement SPD seek to restrict basement development to no more than one storey below the lowest original habitable floor level (though often including exceptions for larger sites) and to a maximum of 50% of each garden or open part of the site. LPAs will assess planning applications on whether they comply with the policies contained within the relevant development plan, the London Plan and the requirements of any SPD.

- An LPA can adopt planning policy to limit the scale of basement development in its borough, provided the policy is adequately explained and justified and it can be shown that all relevant considerations were taken into account. Where a planning policy on basement development is in place, a basement planning application should be decided in line with that policy, unless there is a very good reason not to do so.

What is the future for basement developments?

The days of a multi-level basement are gone. Unless a dwelling has an extant permission for 'iceberg' development (like John Hunt's permission for his Grade II-listed mansion at Kensington Palace Gardens), homeowners will need to modify their grand designs to a more modest, single-storey basement (unless they qualify as a large site).

It seems certain that the ability to rely on permitted development rights will be eroded in many London boroughs through the use of Article 4 directions. RBKC is looking to implement a whole borough restriction coming into effect on 28 April 2016 (consultation on such ended on 8 June 2015), while the Westminster Article 4 direction is set to come into force after 31 July 2016. Only 39 people in 2014 used the permitted development rights for basement works in RBKC, down from 129 in 2013. The imposition of these directions will remove the relevant permitted development rights, obliging an owner to apply for planning permission to carry out the intended work. The consequence will be that LPAs will have greater control over basement development within their areas, both in terms of the scope of the work proposed and the ability to impose appropriate planning conditions that aim to minimise the overall impact the works will have on neighbours' amenity.

Where basement developments have proved controversial in certain boroughs (primarily in central London), it is likely that the requirements of the RBKC BPP will be mirrored and rolled out by those authorities as part of their next local plan review, to control the increasing desire for subterranean development.

Dentons is the world's first polycentric global law firm. A top 20 firm on the Acritas 2015 Global Elite Brand Index, the Firm is committed to challenging the status quo in delivering consistent and uncompromising quality and value in new and inventive ways. Driven to provide clients a competitive edge, and connected to the communities where its clients want to do business, Dentons knows that understanding local cultures is crucial to successfully completing a deal, resolving a dispute or solving a business challenge. Now the world's largest law firm, Dentons' global team builds agile, tailored solutions to meet the local, national and global needs of private and public clients of any size in more than 125 locations serving 50-plus countries. www.dentons.com.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.