The delivery challenge for the next government

Despite significant successes, the improvement in public services has lagged behind public perceptions. Deloitte believes that the conventional top-down target-driven approach has reached the limits of its effectiveness and a new focus is needed from decisionmakers on:

- Developing robust policy-execution models that fully test understanding of customers and ensure effective design of core business processes.

- Developing the commercial capability in the Civil Service to effectively engage the private sector.

- Leading change through engaging the frontline and creating a culture of continuous improvement.

Summary: delivery is the challenge for the next government

Since 2001 the Government’s agenda has focused on delivery, achieving considerable success in targeted areas. The Civil Service has launched numerous initiatives to focus on capability-building, and improving delivery is an explicit part of Permanent Secretaries’ priorities. However, this improvement in delivery of public services has lagged behind public perception. Going forward, there is a real risk of public services being increasingly perceived as both poor in quality and high in cost relative to the private sector.

In addition to the public perception and legitimacy challenges, there are also significant economic challenges: maintaining growth in the UK economy with an increasing proportion of public spending means public sector productivity must improve, and the Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) will involve all departments delivering more whilst operating within limits of lower growth in spending. The introduction of targets, focus on a few key delivery priorities and a top-down performance approach have undoubtedly delivered results, but are in our view reaching the limits of effectiveness – reflecting similar experience in the private sector. The next phase of improving public sector delivery performance will be both harder to get at and yet potentially much more rewarding, because it depends on there being changes to the system of Civil Service delivery and the engagement of the frontline. All systemic change is hard to initiate – especially when some of the easier actions have already been taken, and also because delivering in the public arena has its own inherent difficulties. However the next phase will be more rewarding because, not only will it meet customers’ service expectations, it will provide the Senior Civil Service (SCS) and the frontline with more satisfying involvement.

The major elements of change that we believe will be required are:

- Policy execution

Shifting ministerial and Senior Civil Service focus. Ministers will benefit from directing their focus to policy formulation and driving a delivery governance process that adequately incentivises – and challenges – efficient and effective delivery. The skill for Senior Civil Servants will be to focus, not only on Ministers and policy, but as forcefully to develop robust policy-execution models which halt any tendency to delegate inadequate, high level strategies to the frontline for implementation. Instead, the focus on policy execution will insist on complete understanding of customer segments, will fully test the strategy and operating model and emphasise effective design of core business processes.

- Organising to deliver

Updating the public sector’s performance processes and priorities. This will enable successful delivery through greater clarity of governance and role definitions, so ensuring effective performance dialogue, focus on delivery processes and the building of social capital.

- Using the private sector more effectively

Shifting from creating outsourcing bodies in the image of the public sector to managing and acquiring private sector capability. This will provide a challenging complement to the public sector. Enhanced commercial capabilities, including better negotiation skills based on understanding of the economics and incentives of private sector suppliers, would make government an ‘intelligent customer’.

- Improving the underlying leadership capability of the Civil Service

Orchestrating change. Leading change within complex institutions so that the role of the frontline in generating options for change is emphasised, resulting in the re-launching of the public service ethos.

The principal audience for this paper is the Senior Civil Service – the group of people responsible for enabling the frontline to improve continuously the delivery of public services. Meeting the delivery challenge is not only about improving consumers’ experience of public services and reducing their cost, it is also crucial to improving national productivity, continuing to improve living standards and competitiveness, and maintaining the legitimacy of current levels of taxation. For the Civil Service itself, improving delivery capability is also about establishing a fresh belief in ‘the public service ethos’. Meeting the delivery challenge for the next decade of Government needs to be recognised as the principal contribution expected of a modern Civil Service. The bad news is that there are no quick fixes – the good news is that all the tools are to hand if there is the resolve and will at the top to use them.

1. Context: Lower growth in spending focuses the mind

The rapid growth in public spending over the last 5 years has been a major factor in sustaining UK economic growth and there have been measurable, significant improvements in service in many areas. However, despite hard graft and commitment from the Civil Service, public perception of service quality in health, education, transport and public safety has lagged behind the growth in expenditure and Civil Service performance is not where it needs or wants to be.

|

Deloitte/Ipsos MORI Delivery Index May 2006 |

% net agreeing |

|

This government’s policies will improve the state of Britain’s Public Services |

– 24 |

|

Over the next few years: |

|

|

… the quality of education will get better |

2 |

|

… the quality of the NHS will get better |

– 23 |

|

… the way your area is policed will get better |

0 |

|

… public transport will get better |

2 |

|

… the quality of the environment will get better |

– 18 |

While it is clear that in some areas there have been significant improvements – e.g., cancer and heart disease outcomes, primary school literacy – in others we are still waiting on success. Yet public perception is crucial in maintaining the legitimacy of current levels of taxation. Expectations of service from the public sector have increased in line with increased taxation and in line with improved standards in the private sector; it is no longer acceptable for the public sector to be simultaneously poorer at customer service than banks or utility companies and more expensive to operate.

Productivity and service quality top the agenda

The rapid growth in public spending over the last 5 years has been a significant factor in sustaining the UK economy, with real Government expenditure rising at an average rate of 4.9% per annum since 1999 – well above GDP growth in the same period. Although public spending growth is now decelerating, it will still outstrip the economy’s forecast expansion in the current financial year. However, this rate of increase in spending from 2002-7 is widely recognised as unsustainable. In addition to this macroeconomic case for government to focus on squeezing greater value for money from its spending, there are other powerful drivers of change – productivity, service quality and foreseeable projects.

Although the UK economy has outpaced its major European rivals in terms of national income per head, productivity – the most important indicator of future prosperity – continues to lag behind major EU rivals as well as the US, with French workers 10% and US workers 25% more productive1. Although the private sector also faces significant challenges to match rivals, one of the contributing factors is the growth of the low-productivity public sector in the overall economy and, therefore, meeting the productivity challenge in delivering public services is a high priority for the economy as a whole.

The next government will be under pressure to demonstrate either service quality or to reduce the tax burden – or possibly both. Additionally decision-makers both need and want to demonstrate greater effectiveness in delivering service quality. To achieve this, both the top and the frontline of the Civil Service will come under increased pressure to operate in new ways – in the Senior Civil Service by becoming more effective leaders of delivery and public-private enterprises and on the frontline by becoming more flexible in delivering quality services as well as becoming more productive.

Expectations of service from the public sector have increased in line with increased taxation and in line with improved standards in the private sector; it is no longer acceptable for the public sector to be simultaneously poorer at customer service than banks or utility companies and more expensive to operate.

CSR targets will put all departments under pressure

The current CSR is squeezing future public spending in several dimensions. In order to contain overall spending at the current share of the economy, most departmental spending ambitions will be contained in order to allow continued growth in health and education spending. HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC), the Department for Work & Pensions (DWP) and HM Treasury departments have settled for 5% real per annum decreases. The Home Office is flat in real terms, the Department of Constitutional Affairs (DCA) is decreasing 3.5% real per annum and a number of smaller departments have settled for 5% real per annum decreases. Half the cash saved has been ploughed back into upfront investment to modernise these departments in order to make the sustained efficiencies. Health, education, overseas aid, transport and science – although continuing to grow – will also have to adjust to much lower rates of spending growth than in the past five years.

In addition, major projects remain to be funded and will put additional pressure on public spending – notably the 2012 Olympics, the nuclear deterrent and likely further spending in response to the international security situation.

Within the overall settlements, all departments have committed to a 5% real cut in administration costs to save £1 billion and the CSR has established 3% net cashable savings per annum as the baseline ambition for all departments’ CSR07 value-for-money programmes to save £26 billion. Substantial though the total savings are and difficult though their achievement will be, 3-5% annual reductions in operating costs represent ‘business as usual’ in most of the private sector. The steady drip of critical parliamentary committee reports, National Audit Office (NAO) reports2 casting doubt on achievement of the £21 billion Gershon savings and media exposés reinforce the public perception of insufficient effort to improve productivity in the use of taxpayer money.

Achieving improvements in delivery performance will get even harder

There have been real successes in the last decade – reductions in A&E waiting times, increases in numbers of cases brought to court, primary literacy, electronic vehicle licensing and passport issuing, as well as major projects like congestion charging in central London. Yet these successes may come to be seen as comparatively easily achieved. The setting of targets and the top-down performance management epitomised by the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (PMDU) has driven out focused service improvements but may have reached the limits of its effectiveness. The next wave of improvement – and the sustainability of improvement – depends not on further drive from the top but on creating the capacity across the Civil Service system to promote and encourage improvement, especially from the frontline.

We believe there are four key categories of action required if the government is to achieve a step change in delivery performance. These would catalyse the entire agenda – focusing on policy execution, organising to deliver, utilising the private sector more effectively and increasing the leadership capacity of the Civil Service. We discuss each in turn below.

2. Developing robust policy-execution models

Effective delivery is no trivial task: both tax credits and the Child Support Agency (CSA) were initiatives born out of bipartisan policy support and long debate, but both ran into significant problems of effectiveness and efficiency in implementation. We assert that neither was due to inadequate policy analysis, rushed legislation nor inadequate staff. Their difficulties were due to foreseeable problems in translating an apparently simple proposition into an effective and efficient operating model – problems that would have been foreseen and planned for if there had been robust challenge to a strategic business plan for achieving the policy objective. Tax credits would have been identified as more complicated than the Inland Revenue could deliver, the CSA would have been identified as having a near-impossible remit and both execution strategies were over-reliant on an IT fix. The policy was more than ‘good enough to accept’ but the policy execution was insufficiently tested to be rated – as it should have been – ‘bad enough to reject’.

Instead of prioritising ‘policy execution’ – the leadership task of defining and testing the operating model for the fully-implemented policy – the Senior Civil Service has traditionally recruited, developed and rewarded its high performers for stakeholder-management and a rather conventional approach to policy formulation. Careful, often cautious, policy advice and the protection of Ministers has been viewed as the core task of the best civil servants. Despite 20 years of initiatives going back to ‘Next steps agencies’ and recent Cabinet Secretaries leading a change to a more ‘can do’ approach, bringing outside talent into the Permanent Secretary ranks, articulating a powerful vision of change and promoting the Gershon initiatives to professionalise key functions, the Senior Civil Service is still attached to its traditional model. That model emphasises developing human capital (in the form of talented individuals who formulate policy and advise Ministers) more than social capital (in the form of networks, effective processes and collaboration). Although high-flyers are now expected to experience at least one operational role as they rise through the ranks, there are too many well-known exceptions to give confidence that significant implementation and frontline management is a valued move. But the public and professional commentators are less likely to complain that the policy itself is ‘wrong’ than they are to vent their frustrations that delivery fails to achieve a policy’s promises.

Shift the balance to policy execution

We argue that an increasing share of senior time should be devoted to policy execution – the development, testing and assurance of robust operating models and organisational processes to deliver desired policy outcomes. Policy making is treated as a ‘gift wrapped’ service to Ministers. We propose that it is time to shift the balance of energy and talent in favour of the execution phase – gift wrapping the route to implementation is a more useful leadership task for Governments under delivery pressure.

Implementing a sub-optimal policy exceptionally well can have as much (and perhaps more) positive impact in meeting the needs of citizens, when compared with failing to execute the ‘perfect’ theoretical policy position. Meeting 80% of the policy goals faster and more cheaply would be preferable to apparently meeting 100% – but only after lengthy or expensive delivery issues. Even where this approach is explicitly adopted – for instance with ‘smart acquisition’ of new weapons systems by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) – it has proved difficult to make the trade-offs in favour of incremental delivery or timely rather than complete delivery.

Recognising the logic of prioritising policy execution, the Civil Service would want to improve delivery, regardless of whether the national economy and constraints on public expenditure force the pace. However, such activities are frequently over-delegated by those at the top of the Civil Service. Developing policy without informed consideration of realistic implementation strategies, as well as separating accountability for policy formulation from that of policy execution, are root causes of many public sector delivery shortcomings. Pushing high-flying Civil Servants through short assignments and assessing them on individual accomplishments discourages the joined-up approach, a collaborative style and the building of networks.

Success story – London Congestion Charge

The policy framework for implementing London Congestion Charging was established in the RoCOL (Review of Charging Options for London) report published in March 2000. From mid 2000 to early 2001 Transport for London focused on establishing the execution framework, governance structures (including Director level responsibility for execution) and overall target operating model for the scheme, before beginning to develop the detailed design and procurement requirements. This was one of the keys to the success of the project.

Testing the strategy and operating model

What we are naming ‘policy execution’ defines and tests the operating model for the fully-implemented policy by taking the policy definition and the outcomes sought, and fully challenges each delivery component against that definition and the outcomes. It avoids the ‘strategy gap’ when a new high-level policy goes straight out to the market inviting bids for implementation (usually for a major IT system), missing out the customer segmentation to identify which customers will be served and how (including how customers will be involved in shaping the delivery proposition), business process design and the business case for investment. Some of the most prominent failures, such as the CSA, are examples of this strategy gap. Where there are conflicts (in current versus planned delivery, or in un-joined-up Government) successful policy execution gives visibility and clarity of thinking and offers a framework for resolution. It is this inclusive and open but very focused basis for policy execution that offers the more rigorous foundation for economic/social impact analysis, scenario modelling, financial analysis and customer analysis that should underpin the entire process from policy formulation through execution to implementation. It demands that stakeholders, as well as the policy formulators and those who will become accountable for delivery, are fully signed up. Most of all, it provides a robust basis against which properly to judge subsequent progress, not just towards milestones on a project plan, but about the proper exercise of governance and accountability.

This is more than the longstanding complaint that policy formulation is disconnected from implementation – we argue that there is a missing link in policy execution. The operating model that emerges from rigorous policy execution has three components that will bring it to life:

- business processes from customer contact and case decisions, the strategic procurement process, through cross-departmental activities to IT and estate infrastructure;

- organising for role clarity and responsibility for delivery – governance, structures, management processes, systems and behaviours; and

- governance arrangements that regulate the fact that joined-up customer-centric service means that different elements of the delivery chain will reside in different departments, agencies, local authorities, companies and voluntary organisations – creating relationships, linkages, risks and interdependencies.

Developing policy without informed consideration of realistic implementation strategies, as well as separating accountability for policy formulation from that of policy execution, are root causes of many public sector delivery shortcomings.

This is much more than ‘involving the frontline’ in implementation planning or providing operational input to policy formulation. It is about leaders driving fundamental operational strategy development. It is about a clear definition of the consumer segment being served, the role of government in the policy execution and a focus on business process – moving away from ‘throwing over the fence’ from the policy team to an agent or local government. It demands clear and ongoing accountability and leadership, and requires the policy project team to remain engaged and indeed appraised on feasibility and successful delivery.

Understand customer segments

One of the most startling features of working with the public sector is how little data exists on consumer needs and behaviours. In a world where treating citizens democratically meant treating them equally, then obviously segmented customer views were unnecessary. In today’s world of tailored customer service and targeted government spending, before moving to implementation government must identify segments of consumers with their different needs and likely difficulties to serve, and to develop the appropriate packages of responses to match – rather than a ‘one size fits all’ approach. We believe this can be the norm, not the ideal, with a new top-of-the-office emphasis on policy execution. An example of a successful segmented approach is the German Federal Employment Agency, where rigorous challenge of how policy can be taken forward has simultaneously improved placement rates for the unemployed and reduced its costs by a series of ‘change release’ packages. These packages comprise customer segment, IT, organisation, training and performance management measures – all built around four segments of the unemployed – and six base packages of measures tailored to specific segments rather than by a singular approach. The Varney report on service transformation in the public sector points out that, although there has been progress in the past decade with new customer channels, most departments take a purely transactional approach to their customers, largely leaving it to the citizen to join up the services from different departmental providers. Improved collaboration around customers would also drive out duplication, making customer orientation cost less. Savings should be at least £250-300m p.a. from rationalising face-to-face services and £100m p.a. from reduced contact centre services by the third year of the 2007 CSR and up to £400m over three years from e-service improvement3.

One of the benefits of this strategic policy execution model is that it demands clarity around the role of government in a particular policy arena. With the growth of outsourcing and commissioning and continuing privatisation of state enterprises, the presumption that government should provide services is no longer automatic. The legitimacy conferred by democracy underpins government’s roles in determining national priorities and goals and in applying its monopoly of legal coercion to regulate/allocate the provision of public goods and to correct market inadequacies. It does not automatically make government an effective, efficient and economical provider of services. Indeed, with the private sector continuing to make strides in tailoring services to add value for customers whilst also driving down costs to meet price competition, there is a danger of state-provision being seen as the lower-service and higher-cost option. The motivation of improving delivery in government is not only to provide absolute levels of performance and resources but also to improve the legitimacy of publicly-provided services.

Priority to shaping the fundamental processes of delivering to customers

When we defined policy execution as establishing the best available operating model, it was no accident that we listed business processes first and organisation second in the components of that model. Again in part due to its heritage, there is a Civil Service tendency – encouraged by rapid rotation – to neglect thorough understanding of core, complex business processes such as data collection, customer contact, case management, service delivery, debt management. Global banks and petroleum companies face similar challenges applying their career models to the management of core business processes and risk top management flitting through two-year assignments without acquiring the knowledge of the core processes by which their businesses deliver value. Lack of understanding of process and lack of management experience also encourages the attachment to huge projects and IT solutions rather than incremental development. Implementation discussions frequently spring directly to organisational structure and people before the execution strategy is determined.

The Varney report on service transformation in the public sector points out that, although there has been progress in the past decade with new customer channels, most departments take a purely transactional approach to their customers, largely leaving it to the citizen to join up the services from different departmental providers.

In our experience in arenas as diverse as HMRC, the Passport Agency and the Coal Compensation Scheme, rethinking the basic design of processing customer data and of issuing ‘products’ is one of the largest opportunities to improve the quality of the consumer experience, reducing errors and repeated contacts while also achieving a step-change improvement in productivity. Listening to and equipping front-line staff to understand how they themselves can improve service output whilst reducing operational expenditure (the root causes of errors and unnecessary costs are frequently identical) empowers them, breaks down cynicism about change and renews their belief that they can make a difference.

We commented earlier that the next wave of delivery improvement will come from system-wide initiatives rather than further top-down targets and performance management; turning practitioners into change agents is central to improving the system. The ideal strategy is one that guides the frontline but leaves them sufficient room to deploy their superior knowledge of what can be done to improve performance – providing always that incentives exist to prompt continual improvement rather than complacency, the constant risk in monopoly services. This will, in turn, accelerate the process of convincing taxpayers and customers that they are receiving quality public services and value for money. We observe in both the public and the private sectors that one of the primary disadvantages of the top-down/target-driven approach is that its benefits are frequently disguised by the loss of engagement by the professionals on the front-line. In the public sector where the customers and taxpayers implicitly trust the opinions of frontline professionals – especially in healthcare, education and the military – these professionals must become advocates of change. In our experience this is not wishful thinking about ‘turkeys voting for Christmas’, it is an explicit recognition that engagement by and experimentation in the frontline become the engine of continuous improvement. The top-down phase that many parts of the public sector have experienced serves only to kick-start the process.

The Gershon efficiency programme is intended to be one of many levers of transformation to be applied by decision-makers, but an unfortunate response to the Gershon agenda has been to place too narrow a focus on commodity procurement and shared services in support functions. Whilst there has been some success in achieving savings through this approach, this has too often been accompanied by degradation in internal service quality due to business cases being based on reduction of duplicated management overheads rather than the bigger opportunity to be derived from deep process improvement. Government bodies that have taken the shared service route would benefit from thinking about how they can use the increased customer focus such entities have achieved in order continuously to improve service quality and so further reduce costs. Such initiatives have in many cases also distracted management attention from addressing the issues in the core delivery processes to the public – where the bulk of the expenditure lies and where improvements will actually be seen by the public. Many decision-makers do not understand the need to focus on process and capability – with structure as an enabler – and instead jump to a structural solution such as shared services. ‘Freeing up resources to redeploy to the front line’ contains the implicit but false assumption that the only problem the front line has is an insufficiency of resource. The classic example of this assumption is the NHS, now living with the consequence of pumping money into an organisation without understanding of process, capability and culture. Real effort also needs to go into enabling people to see their contribution to the entire end-to-end process and ensuring a customercentric culture at all stages in the value delivery chain. The efforts that HMRC has made in applying lean thinking to its transactional processes shows what can be achieved with appropriate focus on the front and middle office.

Lean, the application of operations improvement techniques developed in Toyota and now widespread in the manufacturing and financial services industries, is gaining an increasing following in the public sector, and rightly so. However, there is a risk that it can be applied in too mechanistic a way – as a set of tools. Lean is a way of thinking, not just a set of analytical techniques, and has profound cultural and strategic impact on an organisation. Applied properly it will enable front-line staff to contribute enthusiastically to the continuous redesign of day to day activities to remove waste from the system and increase customer focus. It will also bring into question current organisational models, performance measurement systems and large IT investments. Real leadership is required to accept these implications and make changes at the enterprise level as well in the line.

The efforts that HMRC has made in applying lean thinking to its transactional processes shows what can be achieved with appropriate focus on the front and middle office.

Piloting Lean Six Sigma will rapidly expose organisation, IT and customer strategic issues

Policy formulation can be characterised as determining the desired outcomes, any core principles underpinning those outcomes, and defining the role of government. Policy execution can be characterised as identifying the operating model to deliver outcomes within defined roles and authorities. And policy implementation takes that model into detailed design – business processes, organisation design and governance – and the delivery programme.

3. Organising to deliver

There are no quick fixes when it comes to improving either public sector delivery – or indeed underperforming private sector – cultures. In addition, the lead-times in the public sector can be very long before improvement becomes apparent – for example a generational shift in educational attainment, planning and construction time for major transport infrastructure, and lengthy development cycles in weapons systems.

However, this all too often becomes an excuse to accept much slower pick up of change in the machinery of government in areas where there is no intrinsically long implementation requirement. Instead we think a focus on three priority areas of the Civil Service’s organisation could begin to address the problem: first, establishing clarity of roles and responsibilities with clear governance; secondly, ensuring effective performance conversations; and thirdly strengthening the ‘ways of working’ or ‘social capital’ of the organisation – its management values, behaviours, networks and processes that help it deliver in a joinedup way.

Clear governance and roles

Governance issues seriously impede delivery through lack of clarity at the top in terms of conventions governing the relationship between Ministers, Civil Servants and Parliament, compounded by duplication of roles and responsibilities in the delivery chain. Trying to achieve joined-up delivery often results in casting the decision net as widely as possible to share responsibility for advice – no matter how long this takes or how much it weakens the original focus of the policy demand. Achieving clarity in governance and accountabilities has a direct and relatively rapid positive impact on delivery performance, as exhibited both in high-level policy with the independence of the Bank of England and the Financial Services Authority (FSA), and in delivery of specific services such as the Driver & Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA).

It sounds simple – governance arrangements and role clarity need to support effective leaders by enabling clear direction-setting and delegation within the policy execution model and, simultaneously, enabling corporate behaviour across silos. However, over-emphasis on ‘involving’ can burden delivery units with ‘co-ordinating mechanisms’ – for example committee structures which can compromise decision rights. On the other hand, over-emphasis on delivery can lead to high-performing but sub-optimised silos, and lack of top cover for line managers who take the risk to work across silos – as highlighted in DWP’s Capability Review.

In every department or agency that we have worked in, we have observed delivery performance being impeded to some degree by a variety of organisational obstacles – opacity of responsibility for performance, dilution of customer/provider relationships, well-intended but unconsciously-costly interventions by corporate support services, central policy conflicts with delivery agencies, duplication of work due to mistrust of neighbours’ processes and standards, underestimation of the mission-criticality of so-called ‘support services’ in commercially critical issues such as systems and procurement.

Success stories and new challenges – DWP, DEFRA and HMRC

DWP The Pensions Service has delivered improved service and increased productivity through focus on performance but the DWP Capability Review identified the need to counterbalance the success of its major business units by encouraging more corporate ownership and leadership of the department’s agenda.

DEFRA is reorganising to improve delivery capability through the Environment Agency, the Rural Payments Agency etc, recognising that new methods of working together, more project-based work, joint development of policy and sharing of data and services is essential rather than adhering to the 1980s model of arm’s length agencies.

HMRC’s merged organisation established clear accountabilities for line managers of operations, products & processes, and customer groups – but also ensures corporate behaviour through management processes for performance, talent and planning that align all 30-plus businesses.

In every department or agency that we have worked in, we have observed delivery performance being impeded to some degree by a variety of organisational obstacles...

Effective performance conversations

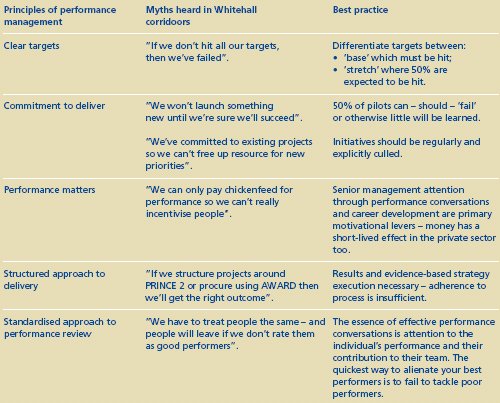

Performance management has become a seriously over-used and abused term – we adhere to Peter Drucker’s original concept of effective ‘management by objectives’ and do not include any concept of ‘managing people out’. The essence of performance management is actually very simple: first, for leaders to set meaningful goals and, secondly, regularly to conduct high quality performance conversations. All the other paraphernalia of metrics and reporting and performance pay etc are ‘nice to have’ inputs to effective performance conversations – but are not essential. Instead of applying this simple formula in a pragmatic and results-oriented approach, a number of disabling myths can threaten the model:

Effective leaders ensure that performance conversations are a continuing feature and distinguish between three different types of performance conversation, all of which are needed:

- formal conversations take place according to a timetable with numerical analyses, metrics, benchmarks, deliverables;

- reflective in-depth conversations take place with senior management in small groups; and

- instant issue-driven conversations provide the ‘moments of truth’ when senior management have to provide feedback and prioritisation.

We deliberately use the word ‘conversation’ – and it helps to set up the conversation well. Many departments set up ‘war rooms’ to manage major programmes and at the Department for Education & Skills (DfES), the Schools Directorate has established ‘the bridge’ – a visually compelling display of its four key policy objectives supported by performance and initiative data that encourages joined-up conversations and encourages potential initiatives to act as complements rather than rivals to existing work.

Building social capital to fully exploit all that human capital

The Senior Civil Service has always been renowned for the quality of its human capital – its raw talent – and that reputation continues to be well-deserved. It is also ‘collegiate but not collaborative’ – a cadre of people who typically enjoy one another’s company but who are not easily persuaded to work effectively together across organisational boundaries, nor easily persuaded to connect with the front-line and the delivery processes of their department. Even allowing for the difficulty of public sector work with its pressures of public scrutiny and ‘hard cases’, this high quality human capital may not be delivering its full potential through lack of focus on social capital – the combination of management values, behaviours, networks and processes that enable an organisation to optimise effectively its human capital. In other words, the social context for civil servants is an explanation for part of the delivery shortfall – just as it frequently is for private sector executives.

This is where the lack of an effective strategic centre to the public sector means there is no automatic home for initiatives to drive new norms of behaviour and performance scrutiny. The combination of unclear governance, inexperienced programme management and low social capital results in the blizzard of projects and programmes that we observe in many departments – under-resourced, in conflict with one another, dissipating management energy and suffering poor project management. One major department currently lists 22 major projects, few of which stand much prospect of delivery. One agency within a major department ran and tracked over 600 projects that overwhelmed management and the noise from which drowned the few critical deliverables, causing a senior manager to observe that "In the private sector, this would be described as over-trading just ahead of insolvency."

We want to see decision-makers encouraged to cull extraneous programmes and pulling the resource into real priorities; providing collaborative incentives and funding to encourage joined-up working; creating transparency to establish new norms of performance; and demonstrating leadership commitment by consistent messages and consistent prioritisation.

4. Using the private sector more effectively

Adopting best practice from the private sector has been part of the public sector mantra for more than two decades, with continued criticism from trades unions and now from the Conservative Party who first championed it. Our view is that the criticism of the principle is misplaced – there is much scope for mutual learning between the public sector and the private sector. The private sector lacks the service ethos, commitment and the brand of public service. The public sector has had successes with the Public Finance Initiative, Independent Sector Treatment Centres and others, but often fails to use private sector expertise effectively; fails to understand how to incentivise the private sector to provide efficient and effective services; and operates procurement and supplier management practices that fall short of best practice.

Take the best from the private sector by fostering competition, permitting failure and providing Incentives

The private sector is motivated by profit. This is not due to some intrinsic moral failing but rather simply because those companies that pay insufficient attention to delivering their services profitably soon go out of business. However this motivation can easily be turned to the public sector’s advantage. As Adam Smith put it "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest."

The public sector has said to the private sector: ‘please come and achieve your service standards, your efficiencies, your return on investment – but you must do it with public service systems, processes and culture’. A new approach is needed. The experience of the many hundreds of private business people who have joined public bodies is a case in point: invited to participate because the public sector wanted ‘private sector-led boards’ for quangos and agencies with tough financial and delivery challenges, but then asked to operate within an environment that made no concessions to the culture and flexibilities that enable high performing private businesses to succeed. On procurement and supplier management, the mantra of ‘value for money’ is an example of the inadequacy of this approach. Value for money is indisputably valid, but in practice too often turns out to be applied as ‘lowest cost’ and ‘barely-adequate will do’. It is much harder to think through the delivery cost-benefit analysis, to test whether a differentiated approach is needed rather than a lowest common denominator.

Professionalising procurement has too often in practice resulted in divorcing procurement from the real end users of products and services and focusing on ensuring compliance with a mechanistic tendering process. Best practice in working with suppliers, as exemplified by companies like Toyota, means procurement professionals working hand in glove with the business to understand their needs and define the requirement; understanding and shaping the supply market and developing sourcing strategies; managing procurements effectively to gain supplier insight and assisting bidders to put forward bids which genuinely understand the need; providing insight on appropriate incentivisation and risk / reward not only on planned outcomes, but also on continuous improvement; and providing ongoing professional supplier management. Public servants sometimes assert that the private sector’s profit motive makes it challenging for private sector suppliers to focus on the needs of the end customer service. But they should remember that Toyota’s suppliers are also motivated by profit and yet Toyota is able to delegate considerable value-add and responsibility to them, and to build partnering and commercial relationships that totally align the suppliers’ activities with Toyota’s needs and those of its own customers.

The ineffectiveness continues where the private sector has taken on the delivery function. Again this may stem from making the private sector conform excessively to public sector norms and from overlooking the factors that actually drive private sector performance. Excluding privatised utilities, there are now a large number of FTSE100 companies that derive a substantial income from providing services that previously were the domain of the public sector – BAE Systems, Serco, Atkins, and Capita. Although some improvement in service and cost has undoubtedly been obtained, much of the potential value has been left on the table due to the public sector’s tacit approach of imposing a public sector model on the private sector. Rather than involving industry at the early stages of projects and inviting real risk- and gainsharing, most deals have involved minimal risk transfer and sought to eliminate the experimentation and potential for failure that is actually the key dynamic of private enterprise. It is no accident that these private sector businesses look and behave very much like the public sector and reproduce many public sector problems and provide fewer private sector remedies than expected.

On procurement and supplier management, the mantra of ‘value for money’ is an example of the inadequacy of this approach. Value for money is indisputably valid, but in practice too often turns out to be applied as ‘lowest cost’ and ‘barely-adequate will do’.

The public sector has recently realised the degree to which its buying power can influence the employment and diversity practices of private sector companies. But deeper understanding by the public sector of how the private sector operates would considerably improve contracting relationships – as would better understanding of public procurement among companies. Part of the challenge is that testing strategies for engaging the private sector is seen as a technical and process role rather than a leadership role. Thinking through operating and outsourcing models to ensure a significant degree of contestability and competition in the markets for the outsourced services; thinking through mitigation and contingency plans so that private operators can be allowed to fail financially without causing unacceptable disruptions to service; understanding better the drivers of the supply bases profitability so that arrangements are structured to give good profits for good service, and the converse; ensuring that contractual arrangements have the right flexibility to deal with changing circumstances and that the contractual terms and business processes are in place to encourage and enable continuous improvement are all essential for the public sector to get the best from the private sector.

However in practice we observe public sector managers talking about ‘allocating’ work to suppliers and the political compulsion to contract for services rather than always maintaining an internal option as a negotiating and assurance tool and – perhaps most damaging of all – the belief that simply contracting for private sector delivery removes risk from the public sector. Public sector managers need to operate in an environment more akin to their private sector counterparts – with greater operational freedom and without frequent policy change and ministerial intervention. Local government may be an example to central government in this arena – for example, the creation of the ‘integrator model’ in Greenwich where a private sector partner has taken on the local authority’s commissioning and project management role.

Transform commercial capability

Transformation of the supplier acquisition and management of the public sector is required. Procurement departments are far too often focused on following process and box ticking as if compliance is a goal in its own right, on ensuring that the process has been fair rather than genuinely ensuring that the public sector is getting best value. The European procurement rules are very unhelpful in this regard but it is possible to work within them effectively. Unfortunately public sector procurement departments are typically below departments’ leadership horizon and rarely have the skills needed in sufficient depth and frequently have to call on external consultants to support major procurements. This can be effective, if expensive, for the most significant of projects, but is inappropriate for the vast bulk of public procurements.

Transformation is about full preparation of commercial options, financing strategies and clarity of objectives on the part of the department. It is depressingly the norm that the public sector does not have full current and historical financial and operating data for the service that may be outsourced and does not understand in advance the drivers of quality and cost. The concept of ‘intelligent client’ is critical – suppliers do have to demonstrate ethics and fair process, but inadequate quality negotiation and delivery management invite poor value for money. A few departments have recognised the need for a ‘Commercial Director’ rather than a procurement manager.

Adopting true best practice is not only about the procurement function, it is also about corporate finance, the users of procured products and services and ultimately the Senior Civil Service being engaged in policy execution. In these circumstances the public sector needs to build a best in class capability for supplier acquisition and management that is a key part of enhanced policy execution capability. Collaboration with the private sector needs to overcome the mindset challenges of the public sector that ‘initiatives cannot fail’, which makes necessary testing and piloting problematic (and therefore makes implementation risk much greater). It is also our view that difficulties arise because Permanent Secretaries are more closely oriented towards Ministers and therefore do not have the operational grasp of senior private sector managers. As a number of departments have done – notably MoD and the Department of Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) – the solution is in part to hire in senior private sector experts to hold top commercial decision-making roles in government.

In summary, for all the rhetoric expended, government could be much more effective in extracting value from the private sector. The remedy is within reach: clarity of strategy, effective negotiation and flexibility to use the private sector more or less according to its performance. This is not about aping the private sector – it is about becoming a best practice public sector manager of the private sector.

Transformation is about full preparation of commercial options, financing strategies and clarity of objectives on the part of the department.

5. Improving the underlying leadership capability of the Civil Service

It is primarily a leadership task to develop successfully the policy execution model, update the public sector’s organisation design and use the private sector more effectively. Therefore our final priority in meeting the delivery challenge is leadership and capability. Some, but not all, departments have seized the Capability Review initiative as a means to increase the pace of reform and upgrade the quality of leadership.

We emphasise leadership because, in our opinion, the public sector is experiencing the same shift in approach to improving delivery performance that many in the private sector have already witnessed. Traditional target-based approaches driven from the top achieve substantial success for a period but, after 3-5 years, begin to suffer from diminishing marginal returns – people begin to game the system, the ‘easy answers’ visible from the top have been accomplished, the next wave of targets offers lesser prizes. In some cases, excessive top-down focus on a few performance indicators can result in management neglecting non-targeted but critical areas that cause operational failure.

Our suggestions for leaders of performance improvement are:

- Exercise care in selecting and driving a few top-down performance targets. Balance the few targets with role descriptions that emphasise management’s holistic responsibility for the long-term health of their business and organisation.

- Move to leading change by engaging the frontline as the engine room of innovation and performance. This will address the fundamental flaws of top-driven performance improvement – opportunities are typically much more visible from the frontline and engaged people tend to game the system less. In a high-performing organisation, the frontline will be offering up options for senior management selection. This is not to abdicate responsibility – senior management are responsible for making clear choices, allocating resources, decentralising responsibility and holding people to account.

Orchestrating change in complex institutions

Leadership already attracts huge effort in the public sector – examples include the plethora of courses offered by the National School of Government and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, the recruitment of private sector people into senior roles to build leadership skills and capacity, the criteria tested in the Capability Reviews, the professionalising of the Finance Directors, the language of the Cabinet Secretary and others in messages to the Civil Service. Nevertheless, there is a widespread perception that the failure to deliver to time and budget and realising benefits is frequently due to a failure of leadership. Given the huge investment in conventional leadership-building, what is missing? We suggest two opportunities: more proactive seeding of change in the complex systems of modern departments, and – as discussed above – improving the public sector’s ways of working.

In a complex system – from all of central government, or all of the public service, to any one major government department – leaders orchestrate effective change typically following a standard pattern (see exhibit):

- Frontline managers and staff experiment with a new approach, reaching out to their network to test ideas and borrow resources, sometimes generating interesting options and acting as role models to the wider organisation. These ‘positive deviants’ are few in number in the top-down culture of the Civil Service but are inordinately important to innovation. They therefore need encouragement to act with courage.

- Decision makers assess the options, endorse and communicate vision and a few key initiatives as the approach for the department or across departments, leading and developing coherent communication.

- Institutionalisation begins by management teams (re-)designing the organisation to:

– Stop killing the initiative as an unintended consequence of its management processes, systems and norms;

– Ensure role clarity;

– Capture innovation from the front-line systematically;

– Ensure the support of the entire organisation is brought to bear.

- Frontline managers embed the new behaviours through capability building – and some will be piloting the next new idea or improvement.

Some, but not all, departments have seized the Capability Review initiative as a means to increase the pace of reform and upgrade the quality of leadership.

Enabling change in complex systems

To ensure the change process works requires management at multiple levels – frontline, business unit management and corporate – to act as leaders. Neglecting the healthy development of any of these phases will be perceived as a failure of leadership – ineffective managers pursuing disconnected initiatives, confused staff hearing multiple messages, old management conventions defeating new ideas. In the Civil Service, one of the principal challenges is that the decision makers confine themselves to policymaking and move on to the next policy challenge – at times almost indifferent to, and seemingly remote from, the implementation challenges being met by the management teams, far less by the frontline. Even while they are in place, the predilection for fire fighting the latest Ministerial concern means that delivery is excessively delegated.

Unfreeze behaviour through structural change

Structural reorganisation always contains the dangers of unforeseen consequences and distracting the attention of management from delivery. It should therefore be reserved for situations where unproductive behaviours are firmly entrenched and management change has been seen to fail. When well-executed, the ‘unfreezing’ effect of a new structure embeds a new delivery ethos – such as the creations of HMRC and the FSA. The potential for displacement activity is illustrated by the debate over dividing the Home Office into a Ministry of Justice and a Ministry of National Security or Interior. If the challenges facing the Home Office are mainly around management of delivery, then a major restructuring is more likely to distract – and one would have to believe that DCA could better manage expanded responsibilities than the current Home Office management.

Success stories – HMRC and FSA

HMRC developed an innovative organisation design with ‘customer’, ‘process & product’, ‘operating’ and ‘corporate’ axes of the organisation – supported by powerful standard management processes and clear governance. The design was developed at remarkable speed from December 2004 through to launch in April 2005, and with a high degree of involvement and enthusiasm from the SCS management. The ‘unfreezing’ effect of the merger encouraged new thinking and set a deadline for achievement. FSA brought together multiple independent regulators to create an organisation that simultaneously delivered clear functional operations and the ‘ideas and partnership’ values of innovative cross-cutting units looking to customer and market issues. Both HMRC and FSA began the structural redesign work by looking at their cadre of SCS, conducting a systematic talent inventory and recognising that their ambition was essentially determined by the ambition and capability of that management group.

A variety of structural tools can be used to unfreeze entrenched behaviours, just as the private sector operates a ‘market for control’ by trading businesses or companies or restructures internally. Apart from mergers or demergers such as HMRC and the Home Office, outsourcing is a structural change intended to unfreeze entrenched behaviours to realise quality and productivity improvements that current management cannot realise. Internal restructuring is frequently the means to bring a fresh view to an old problem. The public sector has analogous options: one powerful structural signal would be to institute a second Permanent Secretary for Operations in every department, with the same rank and standing as (and not reporting to) the policy head. Another option would be to establish across government ‘customer reporting lines’ that would legitimise cross-departmental working – for example the ‘children customer axis’ would link activities across the DfES, Department of Health (DoH), DWP, Home Office, HMRC and local authorities. A third option is to gather up key delivery activities into a dedicated delivery organisation that serves all agencies and business units within a department as an ‘operations function’ behind customer-oriented front-ends. A stronger version of this option would be to create a delivery operation that serves multiple departments – as Service Canada provides a single point of contact to customers of the federal departments. The departmental structure of central government does not pretend to a customer rationale and has evolved incrementally as a set of providers.

Our perspective is to use a structural option cautiously and only after process or leadership change has failed. But when it is used, it is crucial to recognise that its main value is in ‘unfreezing’ behaviours rather than the usual rationale of cost or management or information synergies.

Recapturing the public service ethos

The last issue covered by this paper relates to the quality of talent available in the wider public service, especially in the middle layers just below the Senior Civil Service where implementation and delivery decisions are taken. The Senior Civil Service remains of high individual calibre and many front-line professionals deliver high quality work and respond generously to emergencies. Many blue-chip companies envy the ‘brand appeal’ of the public sector and the commitment of Civil Servants to the inherent value of their roles. However, public sector workers and managers appear to be suffering from lower morale than their private sector counterparts4 and increasing cynicism is visible to many observers. Part of this decline in the public service ethos is due to the impact of aggressive top-down reforms, which may have been an unavoidable kick-start to improve delivery. We argue for a new emphasis on reforming the system to encourage front-line engagement both to improve delivery and to recapture the public service ethos as a force for change.

Apart from mergers or demergers such as HMRC and the Home Office, outsourcing is a structural change intended to unfreeze entrenched behaviours to realise quality and productivity improvements that current management cannot realise.

An additional factor is that there remain a significant number of low-skill and low-will individuals in the middle layers of major delivery departments, actively avoiding taking responsibility for a delivery outcome, bogged-down in process compliance that ensures they cannot be criticised for failing to take a decision – not sensing the cost of continual scope change, delay and lack of clarity. In the past there was a tacit trade-off in the Civil Service: job security and a less-than-demanding working environment in return for less-than-market pay – with a lot of this bargain hidden behind the ‘public service’ label. The public service ethos is important and real for many Civil Servants and needs to be recaptured, but with a greater focus on performance comparable with the private sector. In return, the public sector would provide proper reward and capability-building comparable with the private sector.

The Civil Service needs and is starting to make progress in shifting that bargain, insisting on adequate skills, providing support and qualified teams. The example of the private sector provides both encouragement and warning on this front – many companies that complained of their ‘treacle layer’ have flattened their hierarchies and insisted on performance, but there is increasing evidence of a loss of institutional and technical expertise.

In our view, the ‘public service ethos’ needs to change radically and to learn from private sector mistakes. For the Senior Civil Service, it needs to embrace serving Ministers and serving public delivery as outlined in the Civil Service Code and in the vision for the Civil Service promoted by the Cabinet Secretary – promoting ‘change because we want better service’ rather than ‘change because there’s no new money’ and recognising their responsibility for front-line continuous improvement. For policy-making, it needs to change from ‘the one right answer’ to ‘answers that work for now for different segments – because there is no one right answer and we’ll need different answers tomorrow’. For delivery, we need to move away from ‘empower the frontline’ and ‘value for money – meaning lowest cost regardless of effectiveness’ to insisting on a high standard of policy execution before taxpayers’ money is committed. Leadership is the crucial element – leaders take personal responsibility for outcomes, work with messy partial data, make choices and mitigate risk.

The payoff from closing the leadership gap is not only in terms of delivery to customers – it is also about reinventing the public sector ethos in a persuasive case to inspire civil servants to act as agents of change, whether they work in customer-contact, middle-office or corporate services. These staff are frequently demoralised by the system, their early enthusiasm for public service worn down into passive acceptance of a status quo. They come to believe that change is impossible, and to be deeply suspicious of all management schemes to make improvements. Understanding the root causes of this culture and learning the management tools to overcome it should become keys to career success for Senior Civil Servants. The most important solution is insisting on the right expectations of delivery performance from Permanent Secretaries and their cadres. Meeting the delivery challenge for the next government needs to be recognised as the principal contribution expected of a modern Civil Service. The tools are to hand if there is the resolve at the top to use them.

Meeting the delivery challenge for the next government needs to be recognised as the principal contribution expected of a modern Civil Service.

Areas for action

Developing robust policy execution models

- Shift balance of senior time to delivery leadership.

- Test business strategy against outcomes sought.

- Develop operating model.

- Understand customer segmentation.

- Engage in business process design.

- Design organisation around processes.

Updating the public sector’s ways of working

- Clarify roles and responsibilities to enable direction-setting, delegating, behaving corporately.

- Ensure effective performance conversations.

- Build culture and behaviours through walking the talk, transparency and funding collaboration.

Using the private sector more effectively

- Use the private sector for what it’s good at and ensure competition, failure without catastrophe for customers, and incentives for performance.

- Transform commercial capability in negotiation, contracting, performance data and incentives for performance through recruitment and engaging Senior Civil Servants.

Improving the underlying capability of the Civil Service to deliver results

- Orchestrate change in complex institutions and encourage option development.

- Unfreeze behaviours through selective structural change.

- Re-launch the public service ethos with emphasis on performance.

- Appoint externally.

Footnotes

1 Globalisation in the UK page 44, published by HM Treasury

2 NAO, The Efficiency Programme: A Second Review of Progress, 8th February 2007

3 Service Transformation: A better service for citizens and businesses, a better deal for the taxpayer. Sir David Varney, December 2006

4 Financial Times 30/1/07 p10 Roffey Park Institute

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.