- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

01 Exploring the Global IP Landscape: Insights from WIPO's 2023 Report

In the fast-paced realm of innovation and creativity, intellectual and industrial property rights ("IPRs") stand as cornerstones for safeguarding and incentivizing advancements across various sectors. The World Intellectual Property Organization ("WIPO") has published its annual World Intellectual Property Indicators Report of 2023 ("Report"), offering a comprehensive analysis of global IPR-related activities and developments.

The Report covers patents, utility models, trademarks, industrial designs, microorganisms, plant variety protection and geographical indications. It is built on 2022 data obtained from national and regional IP offices, survey data and industry sources. This article evaluates the key findings and implications outlined in the Report.

1. New Record in Global Patent Filings

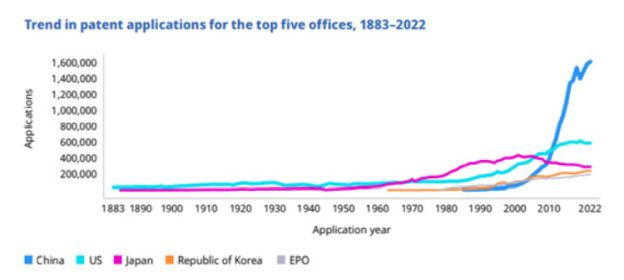

The Report unveils a surge in global patent filings, with 3.46 million applications recorded in 2022, showing a 1.7% increase compared to the preceding year. This is the highest number of patent filings ever recorded. There is a consistent upward long-term trend in global patent applications. The number of patent applications was 1 million in 1995, doubling in 2010 and then climbing to 3.5 million in 2022. This growth underscores the pursuit of innovation and technological breakthroughs across diverse industries.

The China IP Office, with 1.6 million applications, received almost half of all patent applications (i.e., 46.8%). It was followed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office ("USPTO") with around 600,000 applications. Together with the Japan IP Office, the Korean IP Office and the European Patent Office ("EPO"), they comprise the top five offices, receiving almost 85% of all patent applications worldwide.

The top five technologies referred to in global patent applications in 2022 were computer technology, electrical machinery, measurement, medical technology and digital communication. In principle, a patent is granted for 20 years as of the application date. As of 2022, around 17.3 million patents were in force in 137 jurisdictions covered in the Report.

Utility model applications have also increased by 2.9% in 2022, reaching 3 million applications worldwide. 2.95 million of these were filed before the China IP Office.

Turkish Patent Statistics

In 2022, the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office ("TPTO") received 9,119 patent applications. The TPTO granted patents for under half of all applications reviewed in 2022. Türkiye, along with China, had the largest proportion of women inventors in 2022 within the scope of the published Patent Cooperation Treaty ("PCT") applications. Türkiye is ranked fourth globally in utility model applications, with 5,558 applications filed in 2022, showing a double-digit growth (i.e., +23.8%) in comparison to the previous year.

2. A Decline in Global Trademark Applications

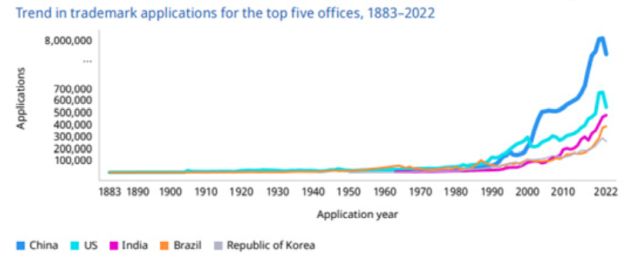

In 2022, the total number of trademark applications plummeted by 16% compared to the previous year. Around 11.8 million trademark applications were filed worldwide. In addition to the number of trademark applications, the total number of classes specified in applications declined from 18.2 million in 2021 to 15.5 million in 2022. Although the 12-year growth trend that has continued since 2009 has ended, the long-term trend in trademark filings is still positive.

Similar to patents and utility models, the China IP Office received the most trademark filings in 2022. It was followed by the USPTO, India, Brazil and Korea IP Offices.

According to the Nice classification statistics, the top five classes specified in global trademark filings in 2022 were class 09, covering scientific instruments, recording equipment, computers and software; class 35, including advertising, business management, business administration and office functions; class 42, covering scientific and technological services, design, and development of computer hardware and software; class 41, including education, entertainment and sporting activities; and class 05, covering pharmaceuticals and dietary supplements.

Türkiye as a Significant Player in Trademarks Landscape

In 2022, Türkiye emerged as a significant player in the global trademark landscape, demonstrating remarkable growth in trademark filing activity. With more than 485,000 trademark applications, Türkiye secured the fourth position worldwide, showcasing a 11.8% growth rate compared to the previous year and surpassing the European Union Intellectual Property Office ("EUIPO").

Non-resident applications contributed around 8% of all trademark filings in Türkiye. Türkiye ascended from seventh to fourth place in trademarks filed by residents. Türkiye also recorded the highest ratio of resident-application class count per million population. The top three sectors specified in trademark applications filed before the TPTO in 2022 were service, agriculture and business.

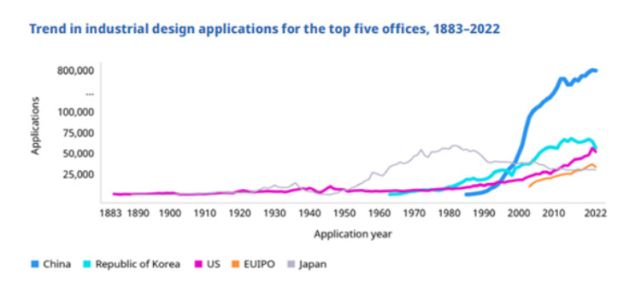

3. A Minor Decline in Global Industrial Design Filings

In 2022, design applications globally saw a slight decline of 3%, totaling 1.1 million applications. China was the top among the IP offices, with 798,112 design applications, followed by the EUIPO and Türkiye. The majority of design applications originated from Asia, comprising 70.3% of all filings, while Europe and North America accounted for 22.4% and 4.4%, respectively. Similar to trademarks, there is a long-term positive trend in global design filings.

In comparison to 45 classes in the Nice classification system for trademarks, there are 32 Locarno classes for designs. The global design filing activity in 2022 concentrated on four industry sectors, namely furniture and household goods, textiles and accessories, tools and machines, and electricity and lighting, respectively.

A Sharp Growth in Türkiye

Türkiye emerged as a significant player in global design filing activity in 2022. With 84,111 industrial design applications, Türkiye secured the third position on the global scale, marking a significant advancement of two positions compared to the previous year. Notably, Türkiye recorded a 27.6% increase in design filing activity, showcasing a strong growth rate. The top sectors in design applications filed before the TPTO were advertising, furniture and household goods, and textiles and accessories.

4. Publishing Industry: Copyrights

The Report also offers publishing industry data from 30 nations that participated in the 2023 global publishing industry survey. Furthermore, 28 national publisher organizations and copyright authorities disclosed their 2022 data. The top five countries in terms of sales income were the US (USD 26.2 billion), Germany (USD 9.9 billion), the UK (USD 5 billion), Italy (USD 3.6 billion) and France (USD 2.9 billion).

Data on the total number of titles published in 2022 covering both the trade and educational sectors are provided by 20 countries. Among them, Türkiye reported a combined 206,674 titles published in 2022. The share of digital/audio-formatted titles was 12.5%. In terms of the data on children's books, Türkiye was a close second, with 17,238 children's books published, right behind France, with 18,535 children's books published.

5. Regional Dynamics and Sectoral Trends

Asia continues to be prominent in the global IP landscape, with the China IP Office receiving the most patent, utility model, trademark and industrial design applications. South Korea and Japan also demonstrated significant contributions, further solidifying Asia's position. In Europe and North America, the US, Germany, and France played pivotal roles in patent and trademark filings, collectively accounting for a substantial portion of global IP activity. These regions remain vital contributors to the innovation ecosystem, fostering collaboration and cross-border partnerships to drive technological advancements.

The Report highlights the growing influence of digital technologies, including artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things in driving IP filings worldwide. This trend portrays the critical role of technology-driven solutions in addressing complex challenges and driving economic growth in the digital age. The biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors also continued to witness robust patent activity, reflecting ongoing investments in research and development.

6. Conclusion

Asia continues to be prominent in the global IP landscape, with the China IP Office receiving the most patent, utility model, trademark and industrial design applications. South Korea and Japan also demonstrated significant contributions, further solidifying Asia's position. In Europe and North America, the US, Germany, and France played pivotal roles in patent and trademark filings, collectively accounting for a substantial portion of global IP activity. These regions remain vital contributors to the innovation ecosystem, fostering collaboration and cross-border partnerships to drive technological advancements.

The Report highlights the growing influence of digital technologies, including artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things in driving IP filings worldwide. This trend portrays the critical role of technology-driven solutions in addressing complex challenges and driving economic growth in the digital age. The biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors also continued to witness robust patent activity, reflecting ongoing investments in research and development.

02 Recent Global Regulatory Developments in Artificial Intelligence and Deepfakes

1. Introduction

Deepfake can be defined as a technology based on artificial intelligence ("AI") that uses deep learning techniques for altering multimedia artifacts through manipulation or creating new ones1. Deepfake has numerous applications across various industries, such as education and entertainment2. In recent years, the rise in its use resulted in challenges to different laws and their application. For instance, the use of AI in moviemaking to de-age actors or simulate previous performances has become a common phenomenon, resulting in concerns over the protection of one's digital likeness3. Last year's Hollywood strikes4 have illuminated compelling challenges at the nexus of AI, intellectual property rights ("IPRs"), personal rights and privacy. Deepfakes are also a matter of public debate, in particular, with regard to intimate images and videos. This has sparked a wider discussion regarding the ethical ramifications of AI.

AI has a lot of potential applications, including improved healthcare, cleaner and safer transportation, more productive manufacturing and more affordable and sustainable energy. Yet, the exponential rise in the use of AI across different industries also presents complex ethical considerations, challenges traditional legal principles and prompts policymakers worldwide to reassess the legal status quo. Against this background, this article discusses the recent developments in AI in general and deepfakes in particular in various jurisdictions.

2. Deepfakes, Copyrights and Personal Rights

In principle, copyright protects original works bearing its authors' characteristics. On the one hand, deepfakes make it easier for original works to be altered and reproduced without permission and be shared online, presenting a challenge to the enforcement of copyrights. On the other hand, the use of copyrighted works in bulk to train deep learning algorithms without permission leads to disputes between the creators of AI systems and rights holders.

AI can also be used to create new works from existing copyright-protected works, blurring the boundaries of typical copyright infringement. AI-generated music that mimics the style of famous musicians highlights its potential to lead to complex disputes. For instance, in the US, the fair use doctrine5 is considered in determining the legality of deepfake creations from a copyright law perspective. Indeed, deepfakes can potentially qualify for protection under the concept of transformative use, similar to parodies. However, the broad application of fair use also raises issues regarding deepfakes created for malicious purposes, highlighting the need for finding a balance between the protection of copyright and freedom of expression.

Deepfake presents unprecedented threats to personal rights and privacy, which include one's voice and personal features. The unauthorized use of AI to manipulate and disseminate disseminate individuals' images and videos challenges existing legal protections and jurisdictional boundaries. Comprehensive legal frameworks are needed to provide adequate safeguards against the unauthorized manipulation of personal identities. Deepfakes also create substantial risks of defamation by fabricating false narratives and false and misleading representations.

3. Addressing the Legal Challenges

Deepfakes challenge the legal systems globally, with some jurisdictions crafting specific legislation to address these issues. In the US, President Biden's Executive Order on AI6, in the European Union ("EU"), the AI Act7, and in the UK, the Online Safety Act8, reflect a growing recognition of the challenges posed by AI and the need to mitigate the adverse effects through regulatory measures.

3.1 US: President Biden's Executive Order on the Safe, Secure and Trustworthy Development and Use of AI

The Executive Order addresses various aspects of AI development, deployment and regulation. While the Executive Order covers a wide range of AI-related topics, including privacy, safety and ethics, its implications for IPRs and deepfakes are notable.

In terms of IPRs, the Executive Order underlines the importance of nurturing innovation and protecting IPRs in the AI ecosystem. It encourages collaboration between government agencies, industry stakeholders and academic institutions to promote responsible AI development while protecting IPRs. This includes initiatives to support AI research, development and commercialization while ensuring IP laws adequately address the unique obstacles that emerged as a result of the rapid development in the field of AI.

Concerning deepfakes, the Executive Order emphasizes the need for enhanced detection and mitigation strategies to combat the spread of AI-generated misinformation and disinformation. It focuses on promoting AI transparency, accountability and security to address the misuse of deepfake technology. By promoting the development of AI tools and techniques for detecting and authenticating digital content, the Executive Order aims to mitigate the harmful effects of deepfakes on individuals, businesses and society in general9.

3.2 EU's AI Act

The EU's AI Act is the first comprehensive regulation on AI by a major regulator. The EU intended to regulate AI as part of its digital strategy to improve the environment for the advancement and application of this cutting-edge technology. The AI Act was approved by the European Parliament on March 13, 2024. Once the regulatory process is completed, it will be published in the Official Journal of the European Union.

The AI Act is a significant step forward in safeguarding the safety and security of citizens from the potential harms of AI systems and protecting individual privacy and human rights. The AI Act aims to classify and regulate AI applications according to their risk level. This classification includes four risk categories ("unacceptable", "high", "limited" and "minimal") and an additional category for general-purpose AI10:

- AI applications considered to represent unacceptable risks are prohibited. This includes AI applications that manipulate human behavior, those that use real-time remote biometric identification, including facial recognition in public spaces, and those used for social scoring and ranking individuals primarily based on their private characteristics, sociomonetary repute or behavior.

- High-risk refers to AI applications that pose significant threats to the health, safety or fundamental rights of individuals. In particular, they consist of AI systems that are used in health, education, recruitment, critical infrastructure management, law enforcement and justice. They are subject to conformity assessments and adhere to safety, transparency and quality requirements. The list of high-risk AI applications can be expanded.

- Limited-risk AI applications are subject to transparency obligations aimed at informing users that they are interacting with an AI system and allowing them to exercise their choices. This category includes, for example, AI applications that make it possible to create or manipulate images, audio or video (such as deepfakes). Except in a few cases, free and open-source models with publicly available parameters fall under this category and are not subject to special requirements.

- Minimal-risk AI applications are used, for example, for video games or spam filters. They are not regulated and Member States are prevented from regulating them further through maximum harmonization.

- For general-purpose AI, transparency requirements apply, with additional and comprehensive assessments when they represent particularly high risks.

3.3 Developments in the UK:

In December 2022, the UK government amended the Online Safety Bill to outlaw all nonconsensual explicit images. It introduced a new duty of care for online platforms, requiring them to act against harmful content. Platforms that fail to fulfill this duty can be fined up to £18 million or 10% of their annual turnover, whichever is higher. It also gives OFCOM (Office of Communications) the power to block access to certain websites. The law also obliges platforms to protect access to and not remove journalistic or "democratically important" content, such as user comments on political parties and issues11. The Online Safety Bill was amended on January 31, 2024, and deepfakes are now covered and defined under law. More serious offenses are also foreseen in cases of sharing explicit images with the intent to cause harm, humiliation and distress.

4. Conclusion: Finding the Balance

As technological developments surge exponentially, laws must quickly adapt to protect individuals' rights without barring innovation. By embracing a comprehensive legal, technological and ethical strategy, societies can navigate the complexities of an AI-driven world while preserving the balance between personal rights and privacy, IPRs and freedom of expression. As such, deepfakes represent a formidable challenge, but with proactive measures and collaborative efforts, it is possible to forge a path forward that preserves the balance in the digital age. Addressing the unique challenges posed by AI and deepfakes requires a multifaceted approach. Strategies may include expanding existing legal protections, developing new legal doctrines tailored to AI, fostering responsible and moderated innovation, enhancing public awareness and establishing effective reporting mechanisms.

03 New AI Guidelines have been published the European Commission, and IP Rights are a Big Part of it

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been a topic of discussion for quite some time. While the actual existence of the AI has found some place between myth and science fiction in the past, it is very much our reality in the modern day. From conducting driverless cars to writing academic articles in seconds, AI has managed to take a place in our lives and our minds, so much so that the authorities around the world sought the need to take action on how to handle AI. A recent development came from the European Commission with the document titled "Living guidelines on the Responsible Use of Generative AI in Research" ("Guidelines"), and IP rights are a big part of it. You can access the full text of the Guidelines via this link.

In the Guidelines, the European Commission cites the following principles for the responsible use of generative AI in research, which are identical to the principles in the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity:

- Reliability: This principle aims to ensure overall quality of the research by confirming the accuracy of the information handled by AI.

- Honesty: This basically means that research using AI must be conducted transparently.

- Respect: While this principles to refers to respect for many other subjects and persons, it is vitally important for IP because it specifically states respect for the intellectual property of others in research using AI.

- Accountability: This principle refers to owning up the results of the research conducted by the AI from start to finish.

Despite being the first document drawing concrete lines for handling AI in research, the Guidelines touch upon various subjects, from recommendations for researchers to recommendations for research organizations. Although it is not yet clear how the inclusion of the intellectual and industrial property rights of third parties in AI-based research will be handled, it is really promising that authorities such as the European Commission has begun taking this topic more seriously.

It is undeniable that we need changes both in the national legislation and in international treaties to disperse any doubts regarding liability issues in AI-based IP infringement cases. For example, we know that certain AI tools are commonly used by people, especially students, to write essays or papers. However, it is not yet known what the consequences of plagiarism issues deriving from AI-created work will be. To our knowledge, Turkish courts are yet to face such challenges, and even if they do, it is not known how they would decide.

In our opinion, it is especially important not to infringe patent rights in AI-led research, as patented products are most likely to be the subject of another scientific research. So, will the AI be able to differentiate the patented products from common products? It is the responsibility of the person handling the AI to input correct commands into AI's system, so that the AI will know its limitations. Will the AI be able to access national and international IP databases to assess the risk of IP infringement? All these questions remain to be answered, even in the Guidelines of the European Commission. It is a good thing that the European Commission has ensured the public that the Guidelines will be updated as the AI technology advances, and they will be reshaped upon the feedback of the public.

We are curious as to whether Turkish authorities will follow this example and issue a guideline of their own in the coming days. It goes without saying that such guidelines will be indispensable as the AI technology becomes more of a part of our lives, and it will require harmonization across the region, especially with the European Union.

04 Precedent Decision of the Court of Cassation's General Assembly Of Civil Chambers on the Infringement of a Trademark Right with the Usage of a Sign Subject to Another Trademark Right in a Trade Name

1. Introduction

Whether the usage of a sign subject to a trademark right by a third party as an essential element of a trade name constitutes infringement of the trademark right has been frequently discussed in doctrine and in judicial decisions, during both the period when the Decree Law No. 556 on the Protection of Trademarks ("Decree") was in force, and since the entry into force of the Industrial Property Law No. 6769 ("IPL").

During the period when the Decree was in force, it was widely accepted that the usage a sign subject to a trademark right by a third party as an essential element of a trade name would only cause an infringement of the trademark right if the disputed trade name was used in a trademark sense. As a matter of fact, the concept of "trademark use" can be defined in the doctrine as "the use of the trademark in such a way as to make it possible for buyers to understand that the goods and/or services bearing the mark are intended to distinguish them from other goods and/or services in terms of their origin."1

On January 10, 2017, with the entry into force of the IPL, discussions on the conditions to be sought for the use of the sign subject to the trademark right in the trade name to constitute infringement of the trademark right continued. At the heart of this discussion was whether the occurrence of infringement of the trademark right was conditional upon the use of the disputed trade name in the trademark sense, just as it was when the Decree was in force. The ongoing discussions were concluded in detail in the decision of the Court of Cassation's General Assembly of Civil Chambers ("CCGACC") dated February 8, 2023 with the File No: 2021/446 and Decision No: 2023/61. The Court of Cassation's General Assembly of the Civil Chamber ruled that if the sign subject to the trademark right is used by a third party as an essential element of a trade name, infringement of the trademark right may occur without the condition that the disputed trade name is used in the trademark sense.

2. Dispute Subject to the Decision of the Court of Cassation

The subject matter of the relevant decision of the Court of Cassation's General Assembly is whether there will be infringement of the trademark right and unfair competition against the plaintiffs due to the use of a trademark registered on behalf of the plaintiffs before the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office ("TPTO") in the trade name of the defendant, which operates in the same or similar sectors with the services covered by the plaintiff's registration. Pursuant to the decision of the Ankara 3rd Civil Court of Intellectual and Industrial Rights ("3rd IP Court of Ankara") dated December 21, 2017 with the File No: 2017/94 and Decision No: 2017/603, it has been determined that the use of the plaintiffs' trademark in the trade name of the defendant will not cause infringement of the trademark right against the plaintiffs, as the plaintiffs have not presented any evidence showing that the disputed trade name is being used in a trademark sense. However, the 3rd IP Court of Ankara, which determined that unfair competition would arise due to the use of the trademark registered on behalf of the plaintiffs as an essential element of the defendant's trade name, partially accepted the case and decided to abandon the trade name subject to the case in accordance with Article 52/1 of the Turkish Commercial Code No. 6102

The plaintiffs filed an appeal before the Ankara Regional Court of Appeal's ("RCA") 20th Civil Chamber against the decision of the Ankara 3rd IP Court, and as a result of the appeal examination, the court ruled that the decision of the 3rd IP Court of Ankara should be annulled, and that if the sign subject to the trademark right is used as an essential element of the trade name of a third party, infringement of the trademark right may occur even if the relevant trade name is not used as a trademark. The defendant appealed against the decision of the 20th Civil Chamber of Ankara RCA. As a result of the appellate review by the 11th Civil Chamber of the Court of Cassation, in line with the jurisprudence during the period when the Decree was in force, the decision of the appellate authority was reversed on the grounds that the use of the sign subject to the trademark right as an essential element of a third party's trade name may only cause infringement of the trademark right if the disputed trade name is used in a trademark sense. The 20th Civil Chamber of Ankara RCA decided to resist. The decision of the Court of Appeal was appealed by the defendant, and the case came before the Court of Cassation's General Assembly ("GA").

3. Court of Cassation's General Assembly Decision

Within the scope of the review made by the Court of Cassation's GA, it was emphasized that there is no reference to the concept of "trademark use" in Articles 7 and 29 of the IPL, which contain regulations on trademark right infringement, and that the regulation in Article 7/3(e) of the IPL essentially consists of the use of the sign as a trade name or business name in the field of commerce, and that this use will cause trademark right infringement pursuant to Article 29/1(a) of the IPL. Although it was accepted that the use of the sign subject to the trademark right by a third party as an essential element of a trade name during the period when the IPL was in force could only cause infringement of the trademark right if the disputed trade name is used in the trademark sense, the Court of Cassation's GA accepted that infringement of the trademark right will occur if the sign is "used as a trade name in the field of commerce" rather than a trademark use with the entry into force of the IPL. In this context, the Court of Cassation's GA determined that the principle that should be taken as a basis in the interpretation of the relevant provisions of the IPL is the "use of the disputed trade name as a trade name in the field of commerce" rather than the use of the disputed trade name as a trade name or trademark, and stated that this principle means the use of the trade name in the commercial field in order to obtain economic gain.

In line with the above-mentioned findings, the Court of Cassation's GA concluded that pursuant to Article 7/2(a) of the IPL, in order for the use of a sign subject to the trademark right by a third party as an essential element of a trade name to constitute infringement of the trademark right, the relevant trade name must be used in the commercial field for the goods or services covered by the trademark registration and for the purpose of obtaining economic gain. The use of the disputed trade name in the commercial field includes the concept of trademark use, but it has a much broader meaning.

In addition to the trademark use of the disputed trade name, any use of the disputed trade name that may harm the other functions of the trademark may constitute infringement of the trademark right pursuant to Articles 7/3(e) and 29/1(a) of the IPL. In particular, in the case of the use of the disputed trade name on service offerings in the commercial field, even if such uses do not qualify as "trademark use," since such uses may fulfill the functions of showing the origin of the service offered and/or distinguishing the services in question from the services of other undertakings, it has been determined that the relevant uses may cause infringement of the trademark right consisting of the same phrase, covering the same or similar services with an earlier date. Accordingly, the Court of Cassation's GA upheld the decision of the 20th Civil Chamber of Ankara RCA.

4. Conclusion

Within the scope of the decision of the Court of Cassation's GA dated February 8, 2023 with the File No: 2021/446 and Decision No: 2023/61, the Court of Cassation concluded that, unlike the jurisprudence during the enforcement period of the Decree, it is not necessary for the disputed trade name to be used in a trademark sense in order to cause infringement of the trademark right. In this respect, the precedent decision of the Court of Cassation's GA clearly establishes that the condition of "trademark use," which was in force during the enforcement period of the Decree, will not be sought in terms of Articles 7/3(e) and 29/1(a) of the IPL.

Footnotes

1. İbrahimli, K. (2023), (pages 11-12) Arising Liability Of Use Of Produced Audios And Images By Deepfake Technology. Istanbul University Institute Of Social Sciences Department Of Private Law, master's thesis.

2. Thorne, C. D. (November 10, 2022), Deepfakes and intellectual property rights. Trademark Lawyer Magazine. https://trademarklawyermagazine.com/deepfakes-and-intellectual-property-rights/.

3 .Stasa, B. (2023), The deepfake conundrum: Balancing innovation, privacy, and intellectual property in the Digital age. JD Supra. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-deepfake-conundrum-balancing-2505505/.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2023_Hollywood_labor_disputes

5. The Copyright Law of the US Title 17 §107.

7. https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/

8. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/50/enacted

9. FACT SHEET: President Biden Issues Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence | The White House

10. EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence | Topics | European Parliament (europa.eu)

11. New laws to better protect victims from abuse of intimate images - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

1. Prof. Dr. Sabih ARKAN, Marka Hakkına Tecavüz - İşaretin Markasal Olarak Kullanılması Zorunluluğu,BATİDER, Yıl 2000, C XX, sayı 3, s. 459.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.