- within Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

- in United States

- in United States

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- within Tax, Energy and Natural Resources and International Law topic(s)

Background: Google's AdTech Services and TCA's Findings

The intersection of competition law and digital markets continues to evolve as authorities confront increasingly complex cases involving dominant online platforms. In this context, the Turkish Competition Authority's ("TCA") 2024 decision1 against Google marks a significant development in digital enforcement under Türkiye's existing antitrust framework. The decision, which resulted in a ₺2.61 billion (about $75 million2) fine and structural remedies, focused on Google's conduct in the AdTech ecosystem — particularly its self-preferencing practices within its publisher ad server services. Against the backdrop of global regulatory momentum and mounting calls for ex-ante intervention, the TCA's ruling offers a revealing case study in how traditional competition tools can be applied to digital markets. This article explores the key findings of the TCA, situates them within the broader international enforcement landscape, and reflects on the ongoing debate between antitrust enforcement and digital market regulation in Türkiye.

Google's Adtech Ecosystem:

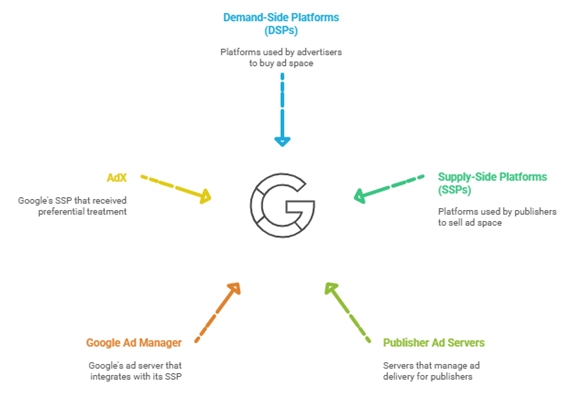

Google operates multiple services in the online advertising supply chain:

- Demand-side platforms ("DSPs"): software platforms that allow advertisers to buy ad space across many websites in real time

- Supply-side platforms ("SSPs"): platforms that help online publishers sell their advertising space.

Google also provides a publisher ad server, a system (Google Ad Manager, formerly DFP) that publishers use to decide which ads to display on their sites. These services were at the center of a TCA investigation concluded in late 2024. The inquiry examined claims that Google leveraged its dominance in certain AdTech services to unfairly favor its own ad platforms.

The Case in Brief

The TCA investigated two main allegations:

- Google used its strong position in the DSP market to steer advertisers towards Google's own SSP (known as Google AdX) instead of rival SSPs, and

- Google exploited its dominance in the publisher ad server market to give preferential treatment to AdX over competing SSPs.

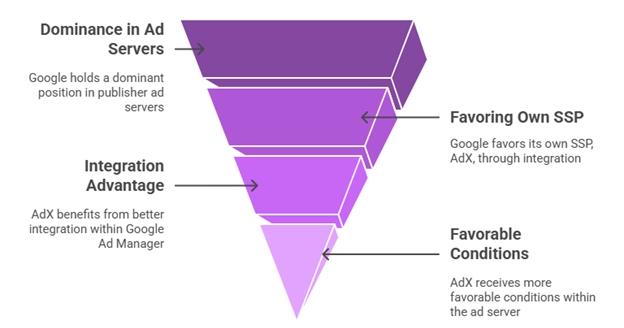

In essence, both claims concerned Google "self-preferencing" – favoring its own services within the AdTech stack to the detriment of competitors. The first allegation (leveraging DSP dominance to benefit Google's SSP) was not substantiated by the evidence: the TCA found Google holds a dominant position in DSP services, but no violation was identified regarding claims that it directed ad inventory purchases from its DSPs exclusively to its own SSP. In contrast, on the second allegation the TCA found an infringement – Google was deemed dominant in publisher ad server services and had granted an unfair advantage to its own SSP through that ad server. The TCA concluded this behavior amounted to unlawful self-preferencing that hindered rivals' ability to compete in the SSP market.

Theory of Harm and Outcome

The TCA's theory of harm was a "leveraging" concern: a dominant firm (Google) using one product (a DSP or ad server, where it is dominant) to distort competition in an adjacent market (SSP services) by favoring its own service3. In the publisher ad server context, the evidence showed Google's ad server practices (such as giving AdX privileged access or integration) made it harder for publishers to use or switch to alternative SSPs, thus foreclosing competition. The investigation involved defining relevant markets for DSP, SSP, and ad server services and analyzing Google's conduct and internal data to see if it undermined competition. Ultimately, the TCA found abuse of dominance in the ad server market. In its decision, the Board imposed an administrative fine of approx. ₺2.61 billion on Google. As a remedy, Google was ordered to ensure within six months that third-party SSPs receive equal treatment – i.e. terms and conditions no less favorable than those for Google's own SSP – when interacting with Google's ad server. This outcome mirrors concerns seen in other jurisdictions (which will be explained in the following section) that dominant AdTech intermediaries should not preference their own services at the expense of competition.

Developments in Other Jurisdictions: Antitrust vs Regulation

Google's advertising technology practices have come under scrutiny worldwide, through both traditional competition enforcement (ex-post investigations) and newer regulatory measures (ex-ante rules). Competition authorities in several jurisdictions have launched antitrust cases similar to the TCA's. For instance, the European Commission opened a formal investigation4 in 2021 into whether Google violated EU competition rules by favoring its own AdTech services in the "ad tech stack" (examining conduct such as Google limiting rivals' access to YouTube's ad inventory and user data and privileging its own tools in auctions). Likewise, France's antitrust authority investigated5 Google's ad server and SSP activities – in 2021 Google agreed to pay a €220 million fine and implement commitments to resolve claims that it favored AdX through its ad server (Google Ad Manager). In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") issued a Statement of Objections6 in 2023 alleging Google's conduct in AdTech is anti-competitive. And in the U.S., the Department of Justice and state attorneys general have brought lawsuits 7accusing Google of monopolizing various digital ad markets, with a federal judge recently finding that Google "willfully acquired and maintained" monopolies in key AdTech segments.

In contrast, regulatory (ex-ante) interventions aim to impose upfront obligations on dominant digital platforms. The European Union's Digital Markets Act ("DMA"), which took effect in 2023, designates large online platforms like Google as "gatekeepers" and subjects them to pro-competitive obligations. For example, the DMA directly prohibits self-preferencing: a gatekeeper is not allowed to rank or treat its own services more favorably than those of third parties on its platforms. It also mandates data portability and interoperability in certain contexts – gatekeepers must enable users to easily port their data to other services and ensure interoperability with third-party services in core areas. These rules are ex-ante – they apply before any specific violation is found, with the goal of preventing harm upfront. This regulatory approach, exemplified by the DMA in the EU, is often contrasted with traditional case-by-case antitrust enforcement, which punishes abuses after the fact. While regulation can be faster in addressing problems (since it imposes clear per se duties on dominant firms), it is also less flexible and can be overinclusive. Each approach has its exemplars: the European Commission's ongoing AdTech case (ex-post) seeks to address Google's conduct through an individualized investigation, whereas the DMA's broad rules (ex-ante) attempt to rein in behaviors like self-preferencing and data hoarding across all gatekeepers.

Competition Law's Flexibility vs Digital Market Regulations

Some commentators argue that only ex-ante regulations can effectively and swiftly tackle digital market issues, pointing out that ex-post competition enforcement is slow and might miss systemic issues. Indeed, Türkiye itself has been considering DMA-like legislative amendments to its competition law, acknowledging in its preamble that "existing rules are applied ex-post and are not effective enough to fix digital market issues," hence the perceived need for ex-ante rules. However, the counterpoint is that competition law has shown a remarkable flexibility (plasticity) to adapt to new digital challenges. Authorities and courts have proven willing to develop novel theories of harm under existing laws – without waiting for new legislation – to address emerging anti-competitive strategies in digital markets.

One prominent example is the "self-preferencing" theory. Historically, a dominant firm favoring its own services might have been hard to fit into classic abuse categories (it's not a straightforward refusal to deal, nor a pricing scheme). Yet competition enforcers crafted self-preferencing as a form of discriminatory abuse. In the EU's Google Shopping case8, the Court of Justice confirmed that a dominant platform favoring its own services (and disadvantaging rivals) can indeed constitute an abuse of dominance when it departs from competition on the merits and harms equally efficient competitors. Notably, the Court explicitly treated self-preferencing as a distinct abuse, not subject to the strict test of the "essential facilities" doctrine (which would normally require proving that access to a facility is indispensable). This doctrinal evolution meant authorities could tackle leveraging conduct without meeting the near-impossible threshold of proving a facility is essential.

Another illustration of competition law's adaptability is the recent Android Auto decision9 by the CJEU. Google had refused to allow a third-party app (offering electric vehicle charging services) to interoperate with its Android Auto in-car platform – a move seen as protecting Google's own mapping app. In a landmark ruling, the Court held that even if Android Auto was not strictly "indispensable" to the rival app (users could still access the service via their phones), Google's refusal to ensure interoperability on a platform designed to accommodate third-party apps could be an abuse. In essence, the Court lowered the bar for intervention: when a dominant platform is meant to be open to third parties, denying access or compatibility can be a violation "even if the platform is not indispensable... but can make the app more attractive to consumers." This demonstrates how traditional abuse categories (like refusal to deal) are being reinterpreted in the digital context – competition law is proving malleable enough to require dominant firms to allow interoperability or data access in situations that wouldn't fit the old framework.

The TCA's own enforcement record bolsters the case that conventional antitrust tools can address digital market issues. In past decisions, the TCA has tackled behaviors analogous to those targeted by the DMA – without special digital legislation. For example, in 2021 the TCA fined Google ₺296 million for favoring its own local search and accommodation services in search results10, which was found to stifle competing vertical search sites. This was essentially a self-preferencing abuse addressed under the existing dominance prohibition. The authority has also shown willingness to consider data-related abuses within the competition law framework. Issues like data portability and interoperability – ensuring that users or business data can be transferred or that services can work together – have been examined by the TCA in the course of cases like Nadirkitap11 or Sahibinden decisions12, leading to remedies aimed at opening up closed ecosystems. These examples suggest that Turkish competition law, through Article 6 of the Competition Act, is capable of evolving to capture new anti-competitive tactics in digital markets.

Conclusion

The Google AdTech decision of 2024 demonstrates that the TCA can employ traditional antitrust principles to complex digital-market conduct, reaching outcomes comparable to those achieved by newer regulatory regimes. While ex-ante regulation like the EU's DMA promises more predictable and swift intervention (by outright banning practices such as self-preferencing or mandating data access), it comes at the cost of rigidity. Competition law's case-by-case approach may be slower, but it offers flexibility and a built-in rule-of-reason that can adapt legal standards to novel fact patterns. Turkish policymakers now face a strategic choice: whether to supplement the TCA's toolkit with DMA-style ex-ante rules or to continue relying on the "plasticity" of existing competition law. The answer may hinge on how effective and timely traditional enforcement is perceived to be. Given the TCA's recent cases in addressing digital markets through Article 6 (and the ever-evolving guidance from courts in the EU on abuses like self-preferencing), one might question if a DMA-like regulation is truly necessary in Türkiye, or if careful, innovative use of competition law can suffice to keep digital markets competitive. The coming years – and the compliance of Google with the TCA's remedies – will shed light on which path is more apt for governing Türkiye's digital economy.

Footnotes

1. Turkish Competition Board's decision dated 12.12.2024 and numbered 24-53/1180-509.

2. The calculation is based on an exchange rate of 1 USD = 34.80 TL, reflecting the Central Bank of Türkiye's buying rate on 12 December 2024.

3. Turkish Competition Board's decision dated 12.12.2024 and numbered 24-53/1180-509, para. 270.

4. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_3143 (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

5. https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/sites/default/files/attachments/2021-07/21-d-11_ven.pdf (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

6. https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/investigation-into-suspected-anti-competitive-conduct-by-google-in-ad-tech (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

7. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-google-monopolizing-digital-advertising-technologies (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

8. https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?language=en&td=ALL&num=C-48/22%20P (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

9.https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=295687&pageIndex=0&doclang=en&mode=req&dir=&occ=first∂=1&cid=20487816 (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

10. https://www.rekabet.gov.tr/en/Guncel/the-periodic-fine-imposed-on-google-in-t-3aa86a822827ef1193cb0050568585c9 (Date Accessed: 02.05.2025)

11. Turkish Competition Board's decision dated 07.04.2022 and numbered 22-16/273-122.

12. Turkish Competition Board's decision dated 17.08.2023 and numbered 23-39/754-263.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.