- within Energy and Natural Resources, Privacy, Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- with readers working within the Media & Information and Retail & Leisure industries

Introduction

The 2023 Electricity Act broke a 50-year federal monopoly, by allowing states to legislate on generation, transmission and distribution within their borders. However, uneven state readiness, mounting sectoral debts and continuing grid fragility have driven calls for a course-correction.The Electricity Act (Amendment) Bill 2025 ("the Bill") is the first substantive attempt to recalibrate Nigeria's 2023 electricity-sectordevolution. While it preserves the spirit of federalism in several areas, most notably by strengthening the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission's (NERC) market-development mandate, it simultaneously re-introduces significant centralising levers that could potentially erode state autonomy. The Bill seeks to clarify regulatory boundaries, de-risk finance, and formalise host-community engagement.

Opportunities

- Clearer investment signals via an explicit 12-month timetable for a sector-wide financing framework and recapitalisation of distribution companies (DisCos).

- Community license to operate through a codified 5% development levy and an enforceable suite of host-community rights and obligations.

- Labour stability anchored on mandatory Minimum Service Agreements that designate electricity as an essential service.

Key Risks

- Regulatory back-sliding: NERC retains "overriding oversight" of intra-state assets connected to the national grid, potentially blunting states' newly-minted constitutional powers.

- Policy volatility: Cross-border trading and new subsidy regimes require ministerial sign-off, re-inserting political discretion into what should be purely economic decisions.

- Fiscal exposure: Expansion of the Power Consumer Assistance Fund (PCAF) without cost-reflective tariffs may deepen the sector's liquidity crisis.

A. Strategic Opportunities

- Independent Market Declaration (s.8) — Deleting the requirement to consult the Minister before NERC declares a competitive market insulates market-opening decisions from day-to-day politics and should accelerate bilateral contracting.

- Financing Framework (s.228J-K) — Mandates a time-bound federal framework for long-term local-currency financing and DisCorecapitalisation, addressing a core investor pain-point.

- Host-Community Regime (s.228N-O) — Embeds ESG principles, by obliging licensees to conduct needs assessments, set aside up to 5% of OPEX for community development, and report transparently.

- Minimum Service Agreements (s.228G-I) — Provides a legal mechanism to avert nationwide blackouts during industrial disputes, a recurring risk since 201

B. Principal concerns and Emerging Risks

- Overriding NERC Oversight (s.230C) — Grants NERC veto power over any intra-state activity that "relies on the national grid," potentially subjecting virtually all grid-connected projects to federal control and diluting state incentives.

- Subsidy Expansion via PCAF (Part XV) — The broadened PCAF mandate lacks an explicit sunset clause or cost-recovery pathway, risking a new quasi-fiscal burden on DisCos and the treasury.

- Ministerial Gatekeeping (s.69 & 126) — Cross-border trade and subsidy disbursement hinge on ministerial policy directives, reducing regulatory predictability.

- Regulatory Vacuum for Non-Compliant States (s.230B) — Deleting the safety-net clause for states without electricity laws could create an interim governance gap if deadlines are missed

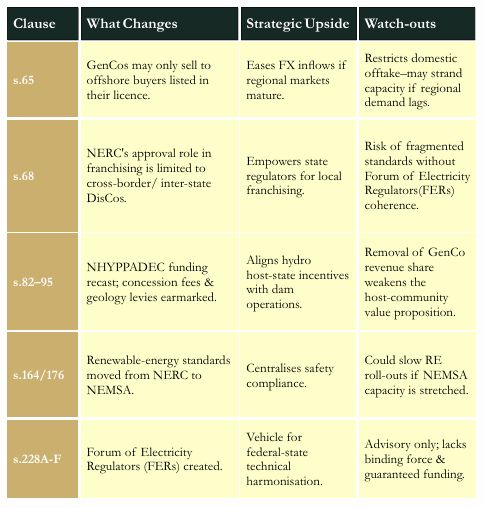

C. Clause-by-Clause Insights

D. Conclusion/Recommendations

The introduction of the Amendment Bill is arguably premature if not hasty. It is not based on any market reaction to the Electricity Act as there has not been enough time given to monitor market developments. Furthermore, it can be argued that a clearer transition period should be allowed between NERC and the State regulators to observe the natural market reaction to these two sets of regulators.

Maintaining momentum on the reforms will first require seamless governance. Transitional federal oversight should remain in place only until every state regulator is firmly established, so consumers and projects never slip into a vacuum. Where short-term financial support is unavoidable, it must be time-bound, tethered to audited consumption data and clearly linked to performance milestones; that discipline protects public funds, while nudging the market towards a more cost-reflective pricing.

Building institutional capacity early is equally critical. Regulators, market operators and dispute-resolution bodies need predictable funding and deep technical benches; without that backbone, the implementation of the new introductions will be ineffective. On the supply side, integrated resource plans should tilt decisively towards embedded and renewable generation, gradually easing dependence on the fragile national grid and bolstering overall system resilience.

For investors, prudent modelling means accommodating the possibility of federal interventions without losing sight of the opportunities that genuine state-level autonomy unlocks. Meanwhile, the sector's social license will hinge on credible host-community engagement: development levies and other community funds must be transparently managed and independently audited if trust is to be sustained. There is general lack of trust in the sector – laws and regulations should be introduced with the aim on driving investments and boosting investor confidence in the sector.

Taken together, these actions can translate the Bill's architecture into durable, bankable growth. However, if override powers remain unchecked and fiscal safeguards are left vague, the liquidity crisis will deepen and investor confidence may falter, undermining the very decentralisation the Bill seeks to advance.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.