- with readers working within the Basic Industries industries

- within Privacy topic(s)

". . . Every law firm is a snowflake—unique in its practice mix, client base, and culture—but all bow to the same unforgiving accounting mathematics. . . ."

Introduction

Imagine you're a law firm manager in 2025, staring at your latest practice group reports when a young data analyst from DOGE barges in. Knowing that you and your management committee are fresh out of your own ideas, you go ahead and sheepishly show him how your average billable hours per lawyer have slipped from 1600 hours a few years ago to now 1500 hours. See W. Josten, The Declining Case for Old School Lawyer Productivity Metrics, Thomson Reuters (Nov. 18, 2024); S. Embry, The Decline of Billable Hours and the Unproductive Partner Dilemma, TechLaw Crossroads (Sep. 6, 2023).

He asks for a little historical context. So, you rewind to the early 1990s, when you started practice, and point out that the landscape was different then: NALP forms routinely pegged expectations at 2000 billable hours per year—50 weeks at 40 hours and two weeks of vacation—not an unreasonable target for aspiring lawyers to hit, with bonuses for the overachievers.

"Hmm. That's not exactly ancient history," he quips. "Now you have all these people just standing around; for sure that's gonna' shred your margins. But . . ." he trails off in thought, "looks like you have a lot of excess capacity ripe for picking. . . ."

"So, how did you get here?" he presses.

Not mentioning that his colleagues in Silicon Valley might have something to do with it, you begin to explain, "Thirty years ago, every big firm boasted a cherished law library—towering shelves of leather-bound volumes—and sprawling file rooms stuffed with boxed documents. No more. . . . "

He gets it and finishes your thought, "So, the IT revolution swapped books for databases, paper for pixels, shrinking the physical footprint of your practice."

"Yes," you agree, "now, any lawyer with a laptop can be a fully functioning law firm."

"I see the problem," he interjects, "Lawyers now do more with less—fewer facilities, fewer people, less time—so naturally hours have been sliding."

He points to a couple of articles he read during his Uber ride over to the firm, and comments, "Looks like people have been writing about how these 'endogenous' technology effects are reshaping the modern law firm and the way you guys work." SeeY. Faulkner, The Escalating Role of Information Technology & Artificial Intelligence in the Practice of Law(Mar. 17, 2021).

"Indeed, they have," you acknowledge.

"I may be new to this," he continues, "but based on this other article I read, the per-attorney hours production metric seems to be THE problem you're having." SeeY. Faulkner, A Primer on Law Firm Profit Maximization ~ Thriving Amidst a Global Pandemic(Apr. 21, 2021).

Either unsure of himself or just testing you, he asks, "Do you think that's a thing? I mean, do you think per-attorney hours production is more prophetic than things like your hourly rates, total hours, or even total revenue?"

Feeling a little uncomfortable with the direction of the conversation, you try to change the topic, "Look. They're all problems. But now, we've got bigger problems. Artificial intelligence ('AI') is turbocharging those, what did you call them, 'endogenous effects.' Now we have predictive coding in e-discovery, and computers are doing a pretty good job drafting contracts and legal briefs."

"So I've heard," he says, "Thomson Reuters might be a little conservative when they say AI will save attorneys up to 12 hours per week by 2029." See Thomson Reuters, AI Set to Save Professionals 12 Hours Per Week by 2029 (Jul. 9, 2024).

Realizing that he did his homework and using some of his own lingo, you respond, "Well, it's worse than that. Now, AI's amplifying what I guess you'd call 'exogenous' technology effects on law firm profits." He tilts his head inquisitively, and you continue, "AI has enabled client self-help strategies."

"How's that?" he queries.

You explain, "Three decades back, clients with a problem were at an utter loss when facing a vast law library all by themselves. They really needed us back then. More recently, law firms competed with Google, but clients still needed to know what questions to ask and how to sift through all those search results. Not anymore. . . ."

"Ah, I see," he responds, adding, "Just last week, I had a problem of my own. All I had to do was jump on ChatGPT and simply explain the problem—'My supplier didn't deliver'—and I got a pretty good idea of what to do about it."

"Right," you respond, "and you didn't call me, did you?"

"Nope. Sure didn't," he smiles wryly.

And so, the conversation continued in that fashion. At each turn, you found the conventional wisdom imparted by the parade of consultants hired by your firm over the years challenged by this young kid. He kept interjecting mathematical objections to your perceived solutions to problems. And through it all, you began to question the value of the income statements and practice group reports produced by your accounting team every month. The kid made bold claims that somehow the firm might make more money by discounting rates on certain "tranches" of time and talked endlessly about "cannibalized hours" eating away at firm profits. He even went so far as to suggest that AI and other tech might somehow enhance firm profitability and liberate its future growth.

Of course, the details of YOUR firm's income statements and billing reports are confidential and can't be published here. So, let's recreate the kid's analysis using data from a hypothetical law firm—which might just bear some close resemblance to yours.

Section 1: Assumptions and the Hypothetical Firm—Profitability Foundations

Every law firm is a snowflake—unique in its practice mix, client base, and culture—but all bow to the same unforgiving accounting mathematics. Your firm might lean into M&A or IP, mine into litigation, but the ledger doesn't care: hours, costs, and rates dictate profit with ruthless precision.

To generalize this reality without drowning in specifics, let's revisit the hypothetical firm from my 2021 Primer on Law Firm Profit Maximization—a stand-in for any firm grappling with the legal tech revolution. First, we'll look at a traditional income statement, a format you know well, then introduce the hourly cost rate ("HCR") and hourly profit rate ("HPR") metrics to reveal how hours production flexes profitability in ways a static income statement obscures—arming you with practical levers to pull in the management of your firm.

The Traditional Income Statement

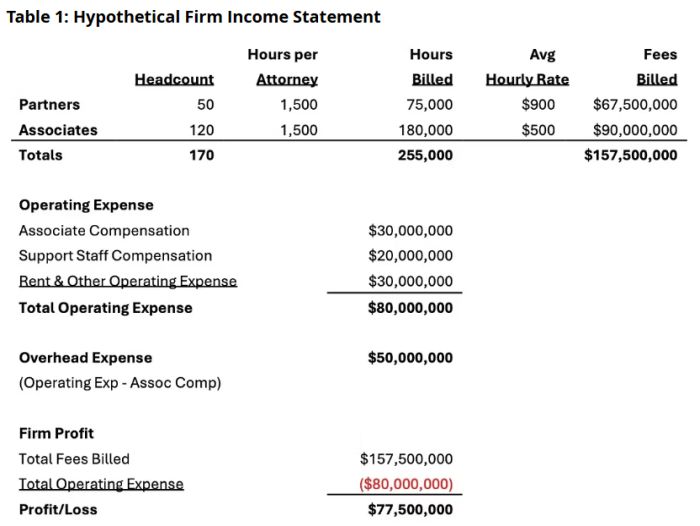

The following income statement envisions a firm of 50 partners and 120 associates—170 lawyers—running at an average annual 1500 billed hours each. Partners bill at an average of $900/hour, associates $500/hour. Operating expense—rent, staff, tech—totals $80 million from which $30 million of associate salary is subtracted to arrive at $50 million of firm overhead. Here's the income statement:

Revenue lands at $157.5 million—$67.5 million from partners, and $90 million from associates. With costs totaling $80 million—$50 million overhead, $30 million associate salaries—this revenue results in $77.5 million profit, a 49% margin. From these data, we can learn a little more about the attorneys' relative contributions to profitability.

Table 2: Attorney Contributions to Profitability

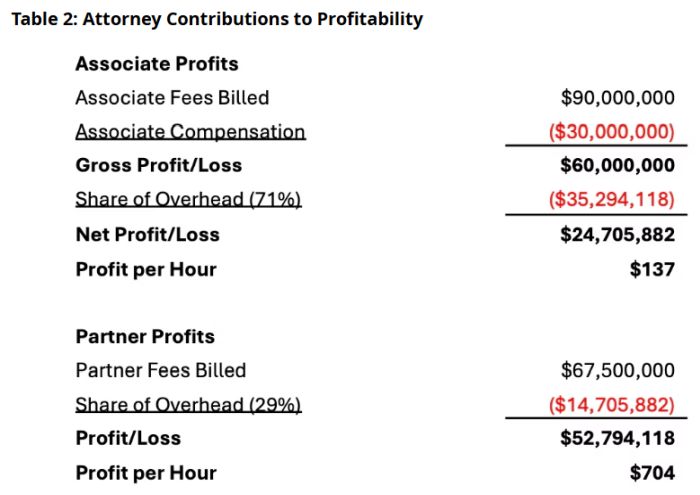

Partners boast a 78% margin ($52.8M ÷ $67.5M), associates a leaner 27% ($24.7M ÷ $90M) thanks to their salaries. Thus, although associates generate far more revenue than partners, their contributions to profitability pale in comparison, contributing $24.7M of profit (a mere $137 per hour billed) compared to $52.8M of profit (a grander $704 per hour billed) by partners.

This is your bread-and-butter report—clear, static, universal. Yet, it does little to explain why you find profits shrinking faster than the retreating hours would suggest or how to fight back.

HCR and HPR do.

HCR and HPR: Seeing Profit Through Hours Billed

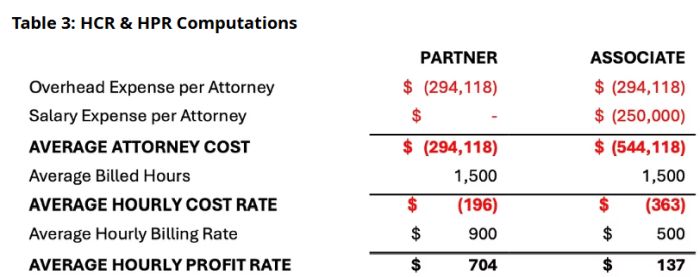

Enter the HCR and HPR tools I forged in 2021 to give law firm managers a dynamic grip on profitability. See Y. Faulkner, Primer on Law Firm Profit Maximization. As shown in the following computations, HCR is your fixed costs—overhead for partners, overhead plus salary for associates—divided by hours billed. HPR is the difference between HCR and the attorneys' hourly rates.

Before moving on, let's point out a critical aspect of this math—because HCR is derived by dividing the fixed value "attorney cost" by the variable "billed hours," the computation is dynamic, producing smaller and smaller HCR values as "billed hours" increase. By "smaller and smaller," I mean it's non-linear. And let's not forget that the computation moves unforgivingly in the opposite direction as "billed hours" shrink. Co-dependent HPR has an inverse relationship with HCR—it gets bigger and bigger as HCR diminishes and vice-versa.

So, the HCR and HPR shown here represent mere snapshots in time—where the cards fell at the close of the firm's annual accounting period. HCR is the hourly "rent" each lawyer pays before profit kicks in. Alternatively, you can think of HCR as a "break-even" hourly billing rate. HPR is what's left over. Multiply HPR by total hours, and you've got profit—an alternative to the income statement for computing attorney profitability:

- Partners: Overhead of $294,118 over 1,500 hours gives an HCR of $196/hour ($294,118 ÷ 1,500). Subtract from $900, and HPR is $704/hour ($900 - $196). Across 75,000 hours, profit is $52,800,000 (75,000 × $704)—dead-on with the income statement.

- Associates: Costs of $544,118 ($294,118 + $250,000) over 1,500 hours yield $363/hour HCR. From $500, HPR is $137/hour ($500 - $363), and 180,000 hours deliver $24,700,000 (180,000 × $137)—right again.

These profit subtotals sum to the income statement's $77.5 million profit computation—nothing groundbreaking yet. But as noted, HCR and HPR aren't linear; they flex (or contract) dynamically with hours billed, showing profit's sensitivity in ways a static margin can't. When hours drop, fixed costs like rent and salaries don't budge—they stretch over fewer hours, pushing HCR higher and shrinking HPR, so profit takes a bigger, non-linear, hit than the hours loss alone implies. When hours rise, those costs spread thinner, resulting in a non-linear lowering of HCR and boosting HPR, driving profit up faster than a simple percentage suggests.

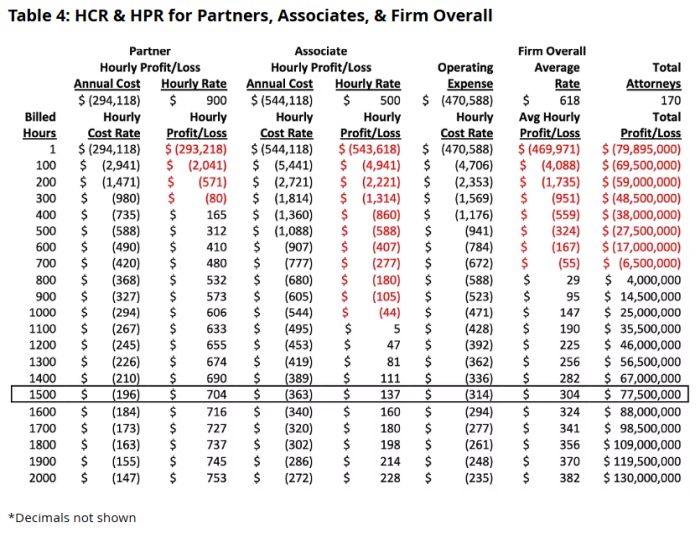

These relationships are best visualized in the following table, which provides a "full-body CT-scan" like view of your firm's accounting.

This is your firm's beating pulse, not just a static ledger entry. The income statement pegs profit at $77.5 million and stops. HCR and HPR play it out: showing more precisely how the firm arrived at its year-end profits. And importantly, the analysis unfolds the dangers lurking when hours billed slide below the firm's 1500 hours average as well as the promise in store if those hours can be expanded.

The table introduces a new firm-wide HCR and HPR lens to the data. Here, we compute HCR and HPR for the firm's mythical "average attorney" by first determining the average attorney's share of the firm's operating expense by dividing total operating expense, $80M, by the number of attorneys, 170, which yields $470,588. The average attorney's HCR is then calculated by dividing that amount by hours billed (1 through 2000) in the table.

The average attorney's hourly rate is determined in similar fashion by dividing total revenue by total hours billed ($157.5M ÷ 255,000), resulting in a firm-wide average hourly rate of $618/hour. Subtracting the average attorney's HCR from that average hourly rate throughout the table creates an ascending schedule of average HPR and resulting firm profits.

The bracketed firm profits ($77.5M) in the table are computed by multiplying the average hours (1500) by average HPR ($304), which is then multiplied by the number of attorneys (170). And as predicted by the income statement, when the average attorney reaches 1500 billed hours, the resulting HCR and HPR indicate $77.5M of firm profit—same profit, new depth.

Section 2: The Escalating Hourly Rate Trap

In view of the firm's downward trending hours production, your role as firm manager places you in a bit of a predicament. At current firm profits ($77.5M), your firm's profit per partner ("PPP") is defensible at $1.55M, but some of your 50 partners could likely do much better elsewhere. Allowing PPP to dip much further might very well encourage your superstars to polish their resumes.

Undoubtedly you have followed the consultants' prevailing advice by implementing time recording, billing, and collections procedures to minimize realization losses. The challenge is not unrealized hours but instead vanishing hours. Those same consultants offer a simple solution—just raise the firm's hourly billing rates.

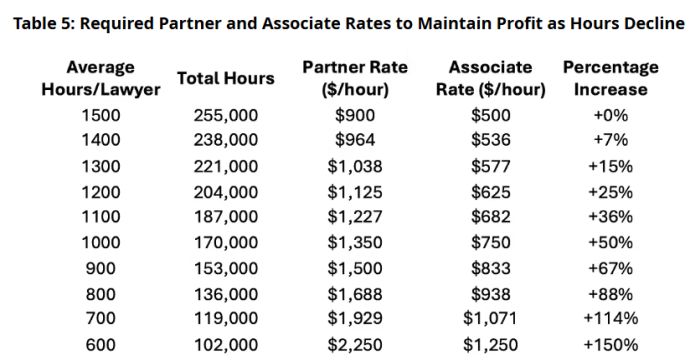

Let's walk through the math to determine just how much the firm must raise rates to maintain each attorney group's profitability across a range of declining average annual hours to produce the status quo $77.5M firm profit. The equation looks like:

HPR(h) = ((r[baseline] x h[baseline]) ÷ h) – HCR(h)

where baselines "r" and "h" are the hourly rate and billed hours respectively for the revenue per attorney at the target status quo profit.

At the status quo here, for example, the partners' hourly rate "r" of $900 multiplied by their average 1500 billed hours produces $1,350,000 of revenue. Thus, when "h" is 1500 in the equation above and divided into $1,350,000, we arrive at the status quo partner HPR, hourly rate, and HCR, where HPR = $900 - $196 = $704.

As shown, the workhorse expression ((r[baseline] x h[baseline]) ÷ h) in the equation produces the adjusted hourly rate R(h). The equation therefore reveals two new insights—the change in the hourly rate and the change in HPR required to maintain current levels of profitability in the face of declining hours. For example, let's compute HPR for partners when "h" is 1400.

HPR(1400) = ($1,350,000 ÷ 1400) – $210 = $754

or

HPR(1400) = $964 – $210 = $754

At 1400 hours, the 50 partners bill their time at the new average rate of $964/hour and produce a total of 70,000 hours (1400 hours x 50), which when multiplied by the new HPR ($754/hour) produces the same $52.8M profit as shown on the income statement. And at 1400 hours, the 120 associates bill their time at the new rate of $536/hour and produce a total of 168,000 hours, which when multiplied by their new HPR ($147/hour) produces the same $24.7M profit recorded on the income statement.

The good news is that bumping average partner rates to $964/hour and average associate rates to $536/hour would appear to be modest adjustments. But keep in mind, those adjustments do not advance the ball on the firm's field of play—they merely maintain the status quo. And if the firm's fundamental problem is declining hours, there needs to be a frank discussion about whether increasing hourly rates will, on balance, do more harm than good. Economists would point to the familiar downward sloping demand curve and reasonably predict that under such circumstances, the firm will ultimately sell less hours at increased rates.

The following table schedules out the escalating average hourly rates required of partners and associates to maintain the firm's $77.5M profit as average hours slide from 1500 hours to 600 hours. Again, that relationship is non-linear and portends trouble for this strategy of raising hourly rates in the face of declining hours.

Take a moment to let these numbers sink in. They jump quickly from the modest to the absurd—placing the firm's management in the position of "catching falling knives" just to maintain the status quo. Recall that these are "average" hourly rates. At 1200 hours, the average partner's hourly rate is $1,125/hour. Presumably there are partners billing their time at significantly greater hourly rates.

While these partners might have competed for work from Fortune 500 clients at their former rates, the new escalating rates might force them to compete for a smaller pool of work from Fortune 100 clients against other firms with stronger brands. And certainly, the higher rates will create tension with existing clients and their budgetary expectations. This ultimately introduces chaos into the firm's accounting and management.

To meet budgets and create the appearance of satisfying the firm's realization targets, attorneys may resort to controlling recorded hours, resulting in artificial realization rates. In other words, they don't record all their time. This, of course, further reduces hours production and increases the firm's hourly cost rates. To remain profitable at those elevated hourly cost rates, the firm must raise hourly billing rates—which only further incentivizes the constraining of recorded hours. And thus, firm management operates blindly in the face of fictitious data, and the firm becomes ensnared in the escalating hourly billing rate trap.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with raising hourly billing rates per se, especially when average hours are expanding toward a threshold of 2000 hours—indicating that demand is outstripping supply. But that is not this firm. Although the data here suggest that firm management might harmlessly tinker with hourly rates at the margin, the solution to the firm's problems must be found elsewhere—in the structure of the firm itself.

Section 3: Excess Capacity—Right-Sizing for Maximum Profits

Before getting to the firm's structure, let's look more closely at how HCR and HPR are operating behind the scenes at this firm. To begin, let's focus on the partners and put a value on their unbilled excess capacity, which is a real opportunity cost to the firm.

If 2000 annually billed hours per attorney is the aspirational goal, then on average each partner is missing that target by 500 hours (roughly 40 hours or one week of billing per month). Across 50 partners, that unbilled excess capacity adds up to 25,000 hours, which, if realized, would increase the partners' billed hours production from 75,000 to 100,000 hours. How much is that lost opportunity worth?

Looking back to the HCR and HPR data in Table 4, we see that when average partner hours are stretched to 2,000, their share of overhead thins to $147/hour HCR ($294,118 ÷ 2,000). Their HPR then rises to an impressive $753/hour ($900 - $147), which yields $75.3M of profit from billing 100,000 hours. That additional $22.5M of profit is a 43% leap from the $52.8M profit they earn when billing an average of 1,500 hours each, outpacing the 33% hours gain by 10%.

That deserves a second look. By increasing the 50 partners' average billed hours output by 500 hours, the partners' $75.3M contribution to firm profit alone nearly matches the $77.5M of profit produced by the firm's 170 lawyers combined!

This begs an uncomfortable question. Did the firm really need 120 associates? Hiring, managing, and supporting 120 associates is a lot of work, especially if the partners might have done just as well without them!

The consultants emphatically insist that associates are profit centers and that increasing associate-to-partner leverage is the ticket to upping PPP and engendering a prosperous partnership. By now, you might be getting the sense that associates might be better viewed less as profit centers and more as either luxuries or as necessary support to facilitate the partners' own profit generation. While this argues in favor of hiring associates with caution, it does not mean that associates fail to contribute to firm profit—they just face a much steeper hill to climb along the way.

As shown in Table 4, the partners in this firm become profitable after billing just 400 hours, but the associates, on the other hand, don't turn a profit until shortly before 1100 hours. This means that the associates worked about 132,000 hours (120 x 1100) just to pay their own salaries and their share of firm overhead. Their $24.7M profit contribution therefore tracks to just slightly over 400 hours of billing that each associate produced, on average, or just a little over 48,000 hours (120 x 400) total. In other words, only about 27% of the associates billed time generated profit.

Putting this all in perspective, the associates billed a total of 180,000 hours to produce $24.7M of firm profit. And while they were doing that, the partners failed to bill 25,000 hours of their capacity worth $22.5M of firm profit. You might wonder, would the firm have been better off if the partners themselves had billed 25,000 of those 180,000 hours instead of the associates?

Let's run the numbers. We already know that when the partners bill an additional 25,000 hours (100,000 total), they produce $75.3M of profit. So now let's see what happens when the firm's 120 associates bill 25,000 hours less. In total, they bill 155,000 hours or 1,292 hours per associate, resulting in a $421/hour HCR ($544,118 ÷ 1,292) and $79/hour HPR ($500 - $421). This HPR produces a $12.2M associate profit contribution ($79 x 155,000). When combined with the partners' $75.3M profit contribution, the firm's total profit rises to $87.5M ($75.3M + $12.2M). In this scenario, by robbing 25,000 hours of work from the associates to fully utilize the partners' billing capacity, the firm is made $10M ($87.5M - $77.5M) better off.

But what if in truth, in arriving at the firm's actual year-end $77.5M profit, the opposite happened—25,000 hours had been effectively "robbed" from partners and given to associates to bill—making the firm $10M worse off?

You can see how that might happen innocently enough, can't you? The 50 partners employ and manage 120 associates. Every month, the partners receive practice group reports detailing the associates' to-date hours progress with reminders to keep them busy—their salaries must be paid after all. And so work that the partners might have done themselves or given to other partners was instead given to associates, keeping the associates busy but ultimately making the firm worse off.

It is precisely this fact scenario that should cause you to have the "cannibalized hours" talk with your management committee. Here's what I mean. It should be obvious from the HCR and HPR data that the partners of this firm have a much more favorable cost structure compared to associates when it comes to profit generation. Let's be clear. This has little to do with billing rates. If partners were to bill their time at the associates' $500/hour rate, they would produce more profit (or generate less loss) at any level of hours production compared to an associate billing at the same rate. The partners' higher hourly rates don't create this disparity, but they do compound it.

Thus, to the extent that associates are cannibalizing partner work, the firm is failing to maximize profits. This creates a useful rule of thumb for law firm partners. When practicable, partners should never delegate work to associates that they themselves have time to do unless the projects are wholly misaligned with the partners' hourly rates.

And wise law firm managers include a discretionary amendment to that rule of thumb which encourages partners to work on "lower value" projects at discounted rates rather than to do nothing. Why? Because pushing a partner's overall billed hours production to, say 2000 hours, lowers the HCR applicable to all hours billed by the partner. In doing so, the partner's discounted time empowers the partner's non-discounted time to produce profits at even loftier HPR.

Perhaps this is not intuitive, so let's look at the following two examples, Partner A and Partner B.

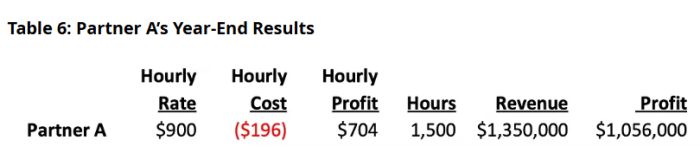

First, Partner A:

Over the years, Partner A had listened intently to consultants who said that the ticket to law firm profitability is maximizing hourly rate realization. Despite having nothing to do on occasion, he nonetheless had opportunities to work on "associate level" projects. But he took a pass on the work because it would have required discounting his hourly rate. In total, he billed 1500 hours at his $900/hour rate to generate $1,056,000 profit, recorded as 100% realization on the firm's books. Partner A's annual compensation review was laudatory and uneventful.

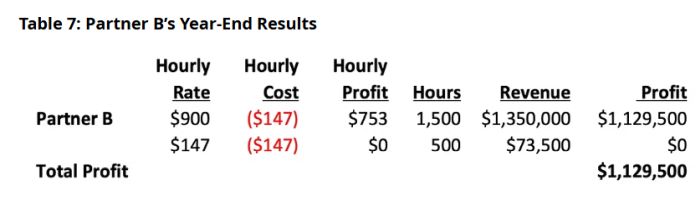

Now, Partner B:

Partner B took a different approach. Due to repeated pre-trial settlements, she was periodically left with nothing to do. So she chipped in to help the firm's paralegals, billing 500 hours of her time at exactly $147 per hour, which produced exactly zero profit. Predictably, the firm's management committee was furious upon learning about Partner B's moonlighting with the paralegals. They even threatened to cut her profit share because her "realization" fell 38% to an effective hourly rate of $565/hour ($1,129,500 ÷ 2000 hours). But might the committee's concerns have been misplaced? As shown by the analysis above, the 1500 hours that Partner B billed at $900/hour, same hours at the same hourly rate as Partner A, produced $1,129,500 of profit—107% of the profit Partner A produced.

Which partner had the better realization; you might muse.

By pushing her total hours to 2000, Partner B lowered her HCR and thereby increased her HPR to $753—$49/hour more than Partner A at the same number of hours billed and at the same $900 hourly rate. How is this possible? By billing 500 hours at $147/hour, Partner B covered an additional $73,500 of her share of firm overhead, thereby raising her profitability by the same amount.

This is the point that our DOGE analyst hinted at in the Introduction, per-attorney (not total) billed hours production is the key driver in law firm profitability. Unlike "total hours" or "hourly billing rates" which require more-specific cost context, "per-attorney hours" is a faithful barometer that measures and predicts profitability. Why? Because when per-attorney hours are maximized, HCR is at its lowest and HPR is at its highest, placing firm profits at their zenith relative to the firm's cost structure. Likewise, when per-attorney hours are mediocre, so are profits.

Of course, in the long run, our hypothetical firm can improve its lot by bringing in more work. But there is a more urgent problem to solve as suggested by the firm's 1500 per-attorney hours averages—the cannibalized hours problem. Here, the cannibalized hours problem is structural—the firm has more attorneys than it needs, as reflected in the 25,000 hours of cannibalized partner billing capacity.

How do we know those hours were cannibalized? Setting hourly rates aside, it's a safe bet that the associates did nothing that the partners themselves could just as easily (and likely more efficiently) have done using their 25,000 hours of otherwise idle capacity.

And in the same way that associates can cannibalize partner work, they can and do cannibalize work from each other. Excess headcount contributes to, if not causes, cannibalization, which increases HCR and reduces HPR across the affected timekeepers—a lead weight on firm profitability. To eliminate hours cannibalization, this firm needs restructuring.

The task ahead is to determine how many attorneys this firm needs to produce its demonstrated annual hours output—255,000 hours. Assuming the firm sets its annual per-attorney billing expectation at 2000 hours, the math is straightforward:

(a) Target Attorney Headcount = 255,000 hours ÷ 2,000 avg hours = 127.5 ~ 127 attorneys

(b) Target Associate Headcount = 127 attorneys – 50 partners = 77 associates

(c) Reduction in Associate Headcount = 77 – 120 = -43 associates

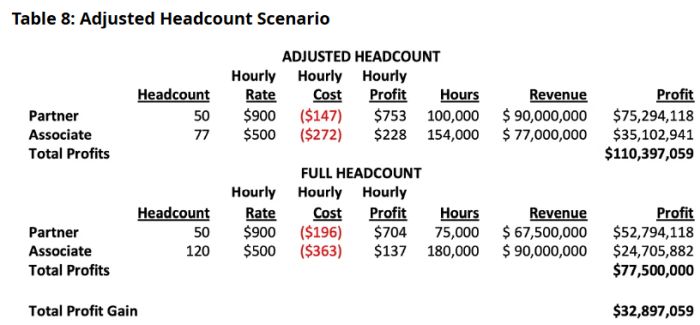

As one might expect from a DOGE audit, the restructuring implied by this math is breathtaking. It suggests laying off 43 associates! And to be clear, this means not only downsizing associate headcount by 36% but also all overhead, including leased office space, technology licenses, malpractice insurance, secretarial and other staff, etc., by 36%. A military-style haircut.

Before your heart gets the better of you, let's examine the impact of this right-sized headcount and firm structure on profitability. One artifact of downsizing by 43 associates in this scenario is the consequence that the firm produces only 254,000 hours instead of 255,000 hours.

At 2000 hours, the 50 partners produce 100,000 hours, but 77 associates produce only 154,000 hours (77 x 2000 hours). Despite this handicap, the results are stunning:

First, the bottom-line numbers. The restructured firm produces $110.4M of profit—a 42% increase of $32.9M over the original $77.5M of profit. Just as dramatic, PPP jumps from $1.55M to $2.2M—all by producing 1,000 hours less in total hours. And let's not forget, this remarkable gain in profitability was achieved without raising any of the firm's hourly billing rates.

We've already discussed the partners' $22.5M jump in profitability—total hours at 100,000, $753/hour HPR, and their resulting $75.3M profit contribution. Even more dramatic are the associates' numbers. At full headcount, 120 associates generate $90M in revenue by billing 180,000 total hours with $137/hour HPR producing only $24.7M profit. Now, just 77 associates billing a total of 154,000 hours and generating $77M of revenue—less hours, less revenue—see their HPR jump to $228/hour and their profit contribution soar to $35.1M.

Finally, the associates in this restructured firm are beginning to look more like profit centers—adding over $700,000 to PPP ($35.1M ÷ 50) and utilizing over 45% of their billed time to generate profits. And this happened, not by increasing associate-to-partner leverage, but by shrinking it.

This is where consultants often "get it wrong"—focusing on revenue generation as a justification for increasing leverage. Here, the temptation would be to conclude that $90M of associate generated revenue by a 2.4:1 associate-partner ratio trumps a 1.6:1 ratio that produces only $67.5M of revenue. The HCR and HPR analyses flip the script and avoids that pitfall by reinforcing that profit, not revenue, generation should dominate hiring decisions.

So, how did all this happen? Of course, much of the increased profitability can be traced to the 36% downsizing of the associates' headcount and their share of overhead. Indeed, costs adjusted sharply downward from $80M to $56.6 million. Let's walk through those savings. Overhead shrank from $50 million to $37.35 million as the firm shed 43 associates (127 × $294,118)—a $12.65M savings from reduced rent, staff, tech, etc. Associate salary expense dropped from $30 million to $19.25 million (77 × $250K), saving an additional $10.75 million. The total savings thus amounts to $23.4M ($80M – $56.6M; alternatively, $12.65M + $10.75M).

That only accounts for $23.4M of the $32.9M increased profit. Where did the additional $9.5M of profit come from? The additional nudge in profit comes from each timekeeper's non-linear increase in HPR as the cost effects of HCR retreat along the path to 2000 billed hours. This shows that all billed hours are not created equally. Each timekeeper's last-billed hour produces more profit than the former along the path to 2000 hours. The partners' 2000th billed hour is 85% profit ($735/hour HPR ÷ $900) compared to 78% at 1500 hours ($704/hour HPR ÷ $900). And the associate's 2000th billed hour is 46% profit ($282/hour HPR ÷ $500) compared to just 27% at 1500 hours ($137/hour HPR ÷ $500).

This accomplishment doesn't just put more money into the partners' pockets, it helps them sleep better at night. Now they are making $32.9M more than before the firm's restructuring and their per-partner share of the firm's operating burden ("PPB") drops from $1.60M ($80M ÷ 50), which slightly exceeded their former $1.55M PPP ($77.5M ÷ 50), to $1.1M ($56.6M ÷ 50), which is now $1.1M less than their current $2.2M PPP ($110.4M ÷ 50). The banks holding the firm's credit lines are undoubtedly much more comfortable with this dramatically reduced PPB and might even be inclined to extend more favorable lending terms to the firm.

Before moving on to the firm's next restructuring steps, let's pause a moment to acknowledge the human cost of this abrupt headcount reduction—the firing of 43 associates. While obviously brutal in its effect, the cruelty was not in firing the associates but instead in hiring 43 more associates than the firm needed and could reasonably mentor. Instead of turning the associates loose into an abundant savannah, the firm instead thrust them into a scarce desert to compete for a limited pool of billable work—the law firm version of "Hunger Games." So let's place responsibility for this tragedy where it belongs. Unquestionably well credentialed and capable enough to be welcomed by the firm's hiring committee, most of these associates would have otherwise thrived in a firm that had exercised more care in its hiring. The HCR and HPR analyses described here are not only good for law firm partners but also for the next generations of lawyers who will someday fill their shoes.

Section 4: Right-Mixing for Maximized Profits

While exercising care in hiring associates both optimizes their profitability and ensures intra-firm demand for their work, today's associates, especially junior associates, face growing headwinds from our DOGE analyst's so-called "endogenous" technology effects. In decades past, junior associates routinely cut their teeth on extended document review projects and legal research while combing through the firm's library shelves.

No more. Document review is routinely farmed out to vendors who employ armies of contract lawyers—soon to be replaced by AI agents. As for legal research, the prevalence of electronic databases may have relocated research from the library to the office desk, but it impinged little on the associates' role in drafting legal memoranda and strategy documents. That role too is being replaced by AI agents.

With traditional entry-level work drying up, newly hired junior associates face more immediacy in stepping into traditional "mid-level" associate roles. For law school graduates applying to firms, this is welcome news to the ambitious but creates rocky transitions for the late bloomers. Both groups, however, face challenging competition for these mid-level responsibilities from lateral associate candidates with proven track records. While troubling for junior associates, these economic forces are reshaping the modern law firm in ways that enhance profitability.

Recall that the hypothetical law firm's overall average hourly billing rate is only $618/hour ($157.5M revenue ÷ 255K hours)—a slight bump up from the associates' average rate of $500 per hour and a significant retreat from the partners' $900 per hour average rate. This means that, all else equal, had the firm's attorneys billed all their time at $618 per hour, the profit entry on the firm's income statement would look the same. It further means that the firm's average HPR is a mere $304 of profit per hour ($77.5M profit ÷ 255K hours). That's not much profit per hour, especially in view of those partners toiling away at hourly rates well above the partners' $900/hour average.

But by restructuring the firm's headcount, the firm's average hourly billing rate rose to $657/hour ($167M revenue ÷ 254K hours) and average HPR increased to approximately $435 of profit per hour ($110.4M profit ÷ 254K hours). How? By eliminating cannibalized hours and reducing associate headcount, the firm both increased revenue and altered the mix of timekeepers who billed essentially the same number of hours. Given that new mix of timekeepers, both the average hourly billing rate and average HPR skewed upward.

Thus, a further refinement to the work of law firm restructuring involves optimizing the mix of timekeepers to maximize those two metrics. Here, despite some improvement in the average billing rate and average HPR, our adjusted headcount scenario fails to reflect an optimally restructured law firm. That scenario assumed that the associate headcount was reduced in such a way that preserved the $500/hour average associate billing rate. As discussed above, the economic forces at work on associate hiring decisions favor mid-level to senior associates over junior associates. Those forces apply equally to downsizing decisions.

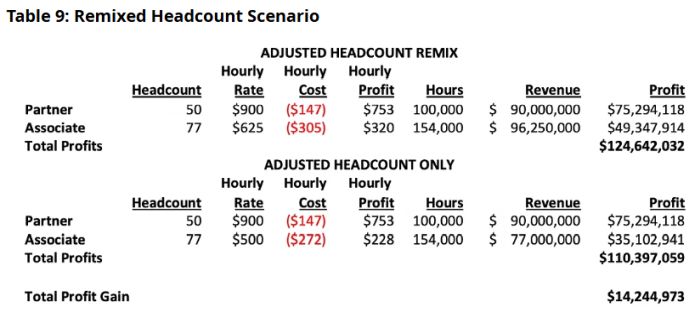

Let's see what happens when the 43 associates in the hypothetical law firm are dismissed selectively in a way that skews the remaining 77 associates more heavily toward mid-level and senior associates. In doing so, we assume that the average associate salary expense increases from $250K to $315K and the resulting average associate billing rate increases from $500/hour to $625/hour. Associate share of overhead expense remains at $294,118. The per associate attorney cost thus equals $609,118 ($294,118 + $315,000). At 2000 hours, HCR equals $304.56/hour ($609,118 ÷ 2000 hours), and HPR equals $320.44/hour ($625 – $304.56).

Again, our 50 partners bill 100,000 total hours at an average of 2000 hours per partner. And at 2000 hours each, our 77 associates bill a total of 154,000 hours. No change in hours.

Here, of course, partner revenue and profits remain unchanged. But the associates' revenue increases from $77M to $96.3M while their profit contribution jumps $14.2M from $35.1M to $49.3M. Total firm profit increases by the same amount from $110.4M to $124.6M. The partner's PPP nudges up to $2.5M.

Coming full circle, the total firm profit produced by the restructured and re-mixed firm of 127 attorneys is now $47.1M greater than the $77.5M profit produced by the original 170-attorney firm. And keep in mind, this astounding 61% profit surge was accomplished by billing 1000 less total hours and without raising the hourly rate of a single firm timekeeper!

Let's look a little more closely at how the remixed and restructured associates performed. Originally, 120 associates billed 180,000 hours to produce $90M of revenue and $24.7M of profit. In this latest scenario, 77 associates bill just 154,000 hours and produce roughly the same revenue, $96M. And in doing so, they double their profit production, generating $49.3M of profit.

The firm's average performance data likewise improved. The average hourly billing rate rose to $733/hour ($186.2M ÷ 254,000 hours), up from $618/hour in the original scenario. And at average HPR of $491/hour ($124.6M ÷ 254,000 hours), the firm is now adding profit per hour at nearly the same rate at which the associates originally added revenue per hour at their average hourly rate of $500/hour.

* * *

After presenting these data to your partners at the annual retreat, you receive a standing ovation. The partners, of course, are delighted with these results and their new-found prosperity. However, as the microphone is passed around for comments, a few common themes develop. Several partners mention that they are seizing opportunities to expand their practices and feel the need to hire more associates to support that work, especially associates with specialized skills and expertise. And others note that the firm's hourly billing rate structure is lagging behind industry averages and question whether it is time to raise rates.

Without waiting for the microphone, the DOGE analyst speaks up from the back of the room, "You're all spot on!" he announces and then adds in an even louder voice for emphasis, "But let's do it the right way. . . !"

Section 5: The Virtual Leap—Overhead's Final Frontier

Interested in what the kid is about to say, the partners quickly pass the microphone hand-to-hand in his direction as he walks toward the overhead projector at the front of the room.

After mounting the microphone on its post, he begins his impromptu remarks.

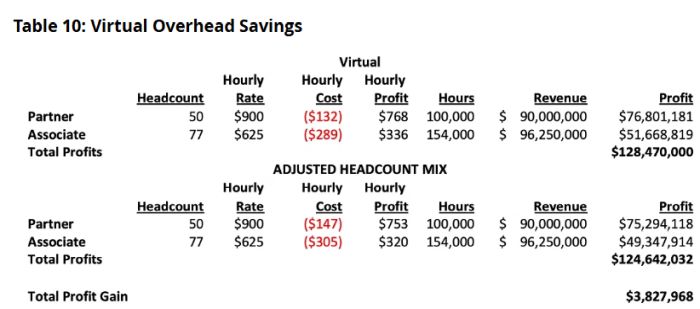

"Up 'til now," he said, "we've focused on optimizing headcounts, timekeeper mix, and eliminating cannibalized hours—those things turned out pretty well I'd say." He continued, "There's one final frontier of profit maximization to discuss—minimizing firm overhead." Looking at the firm's CFO and CTO, he admonished, "Anything that lowers overhead will reduce HCR and increase HPR—I leave it to you bean counter and IT guys to figure out what further cuts and efficiencies can be found."

Turning to the partners, he said, "But there is one more big decision for you guys to make and its pretty fundamental to your overhead and will dictate the future growth of your firm—and don't think I haven't heard your comments about my colleagues in Silicon Valley—you have them to thank for what I'm going to say next."

He then grabs a blank transparency slide and places it on the projector with one hand and begins writing down numbers with a marking pen in the other.

He explains that before restructuring, firm overhead was $50M ($294,118/attorney x 170 attorneys) which, consistent with industry averages, ran about 30% of the firm's total revenue of $157.5M. After restructuring, firm overhead sunk to $37.4M ($294,118/attorney x 127 attorneys), running about 20% of the firm's current $186.3M of revenue. Getting to his point, he says, "So, that's pretty good but you've got these virtual firms out there that say their overhead runs 18-20%—about where you're at now but you aren't virtual."

He pauses for emphasis and then declares, "It's nice and all but you don't need your building," and then adds, "I've been walking around that place for the past few weeks and it's a ghost town."

Ignoring the growing murmurs, he asserts, "Conservatively, you can get overhead down to the low range at 18% and when you do, things will look like this. . . ."

He then scribbles the following onto the transparency slide:

"There, see!" he beams while going on to explain, "That extra 3% takes care of the building and maybe some change."

Breaking the awkward silence that followed, one partner speaks up, "I may not be as quick at math as you but that $3.8M savings is only about $77K per partner." She adds, "We're all doing pretty well for ourselves now—I think we can afford the building."

The DOGE analyst squints his eyes as he searches for the speaker. Finding her, he asks, "Aren't you the one who just said you need to hire these specialized associates?"

"I am," she answers in a near whisper.

"Just where do you think you are going to find them?" he asks rhetorically. "I mean, these are finance guys right?" She nods affirmatively. "Thought so," he says and continues, "I've done some M&A myself and no offense, but there aren't many of those guys living around here."

He goes on to explain that they won't miss the building, especially as they start expanding again—"won't need to worry about rising rents." And the savings will help cover the employment search and hiring expense—"headhunters and all." And by going virtual, the firm is freed up to find the best talent "literally anywhere on the planet." And yes, his colleagues in Silicon Valley created videoconferencing and online collaboration tools that make it feel like "you're in the same room together wherever you happen to be."

Without catching a breath, he adds, "And that 3% savings can help you hold off a bit on raising your rates." "Look," he cautions, "I know a few things about new product launches—it never really goes as planned." Sensing the quizzical stares, he adds, "You're going to be competing with the big guys and no way you're going to be as efficient as them right out'a the gate—your lower rates will help you get the work in the first place and keep the client spend where it should be."

With a faint air of defiance, a more senior partner stands up to proclaim, "It can't all just be about money. I mean, the building has intangible value—we need facetime with our partners and associates to build teamwork."

The DOGE analyst frowns.

The partner sitting in the chair next to the speaker takes the microphone and says, "I don't disagree with Bob, here, but I was just thinking. Bob and I are on opposite floors, and we've been working together on cases for the past ten years." Turning toward Bob, he asks, "I guess, I have a question for you, Bob, when was the last time either of us actually got on the elevator to go talk to each other face to face?"

A bit flustered, Bob takes back the microphone and concedes, "That's a fair point. We pretty much just email each other, don't we. And honestly, I'm not sure when we even last spoke on the phone together—it might be nice to at least videoconference once in a while."

The microphone is then passed up to the next row after another partner stands to speak, "As everyone knows, I lateraled here from a big global firm, offices all over the U.S. and the world. As I think about it, that firm has all these beautiful offices, but it operates as a virtual firm—it has to. All the lawyers in my practice group were in different cities, so I pretty much only saw them online. Frankly, nobody knew or cared if the other lawyers on a call were in their offices or some other place."

With the ice breaking, one of the newest partners spoke up to say, "I don't want to put words in his mouth, but I think what our DOGE friend here is saying is that our building is costing us much more than we pay for the lease. It seems he has a bigger vision of what our firm can be than we do. . . ."

And so the conversation continued with growing consensus and a final vote to "go virtual." The partners decided to immediately sublease their building space to the telemarketing firm that had been calling them every week asking about availability. The DOGE analyst was pleased with the decision, having determined that market conditions would allow them to sublease the space at a substantial premium. . . .

Section 6: Scaling the Optimized Firm—Growth with Precision

The following year was a beehive of activity at the firm. Flush with cash, the partners found new and effective ways online to broadly promote themselves, their practices, and firm to an ever-wider audience of potential new clients. The partners indeed introduced new and high-valued services. With per-attorney hours straining past 2000 hours, the firm also began raising hourly rates strategically with an eye to creating flexible rate structures, allowing the partners to price their time appropriately for the specific services provided to clients. Each partner no longer had "an hourly rate" but a menu of rates that facilitated involvement in all aspects of each matter.

And as the DOGE analyst predicted, the firm was surprisingly successful in finding and recruiting associate talent with skills suitably matched to the partners' practices. Because the firm was now virtual, the hiring committee found these extraordinary candidates willing to make concessions in their salary demands. Joining the firm didn't require them to upend their lives and move to a new city. Some preferred to stay "close to home," others preferred life on one of the coasts or in the mountains near the slopes, and yet others seemed to be nomadic—interesting and magnetic people with a knack for attracting clients of their own. The promise of a growing and prosperous partnership had never been brighter.

The partners too began to disperse around the country—not only enriching their own individual lives but also exposing the firm's practices "locally" and "personally" in key markets and in ways that online outreach could not. One partner relocated to London, another to Singapore, and yet another to Tokyo. Almost overnight, the firm became a "global law firm," and the partners increasingly found that they had to include interpreters in their online client meetings.

Nobody ever mentioned the building again.

The only real complaint that you, as firm manager, received from the partners concerned the growing complexity of their income tax reporting—expanding piles of "composite" tax returns for various states and even foreign countries.

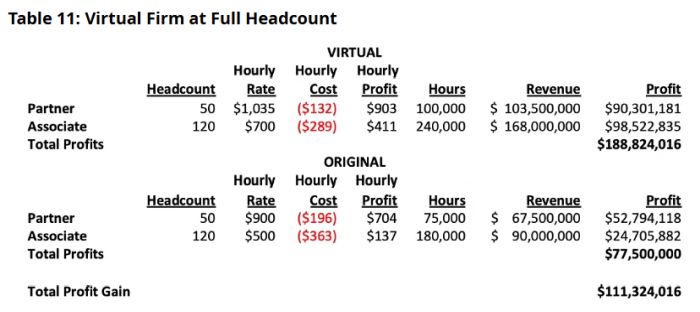

And so, two years after the "go virtual" partnership vote, you sit down to prepare slides for the upcoming retreat and to report on the firm's progress. Coincidentally, during those two years, the firm hired 43 associates, and once again the firm has a 170-attorney headcount. Yet, this time, per attorney hours averages are holding strong at 2000 hours. Everyone keeps mentioning how much easier it is to bill hours when you aren't stuck on the highway everyday commuting to and from the office.

You note in your slides that the firm raised hourly rates cautiously. Average associate rates increased 12% to an average of $700/hour with the help of right-mixing the associate classes. Partner rates increased on average by 15% to $1,035/hour. Your CFO and CTO worked tirelessly to constrain overhead, preserving the same HCR numbers that the DOGE analyst etched on to the transparency slide during his remarks two years before. The hourly rate increases gently coaxed the HPR numbers up—solid for the associates, and the partners now turn profits per hour at an amount exceeding their old average hourly billing rate.

Even you are shocked by the firm's performance for the year compared to its numbers when the DOGE analyst first burst into your office:

You feel a real sense of satisfaction in anticipating your partners' reaction to the announcement of the final tally for the year—$188,824,016 of profit.

As it happened, rather than rising in applause, your partners sat in silent disbelief. Just a few years before, they had reflexively patted each other on the back for producing $77.5M of profit. This year, they produced 244% of that amount—an additional $111.3M dollars of profit—all while working on average about 40 hours a week and enjoying two weeks of vacation. The firm's PPP is now an enviable $3.8M.

The eventual celebration of that accomplishment was soon followed by energetic forward-thinking discussion. There was consensus that the cost savings from "going virtual" was inconsequential compared to its real winning power—flexibility. The hiring committee commented that well-known partners at other firms with lucrative practices had "put out feelers" to see if there was any possibility of joining the firm. Other partners reported on successes in forming case-by-case collaborations with smaller and even solo firms that allowed them to expand their work into specialized areas without simultaneously expanding the partners' PPB (per partner overhead burden). Even AI was sharpening the firm's competitive edge, placing the firm's attorneys on a more even playing field with Big Law's mega firms in terms of analytical prowess and project turnaround.

Someone commented, "The sky is now the limit."

Conclusion

That comment prompted the partners to think of the DOGE analyst. They recalled with some amusement his grand plans for building time shares on Mars. Privately, they each reflected that achieving $188.8M of annual profit for a once-obscure 50-partner law firm was an equally unlikely objective. They wondered what the kid might be up to now. One partner had heard that he was busy using AI to read and decipher CT scans of old petrified Greek scrolls and that he was "having some success."

They all agreed that they learned a lot from the kid. Mostly, they learned that "having some success" requires thinking BIG while putting emotions aside and seeing problems plainly. A little math seems to go a long way too. They all smiled when one partner commented, "Thanks to the kid, I never make a decision now without wondering what will happen to the firm's HCR and HPR."

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.